#xx век

Vyacheslav Koleichuk. Cube.

1982. State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Viacheslav Koleichuk (born 1941, Stepantsevo, Moscow) is a Russian sound artist, musician, architect and visual artist. Koleichuk mainly makes installation art that involves tensegrity. Sometimes these sculptures function as an experimental musical instrument during performances. Some of his works are part of the collection of the Kolodzei Art Foundation. He was a member of (Lev Valdemarovich Nussberg’s) kinetic art movement Dvizhenie in the 60s.

This work is based on the famous masterpiece by Ivan Aivazovsky - The Ninth Wave.

Post link

Boris Kustodiev. Venice.

1913. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

Boris Kustodiev went to Italy immediately after he had successfully defended his diploma thesis at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, where he had studied under Ilya Repin. He left for Europe with his young wife and newly born son - in the few months they spent abroad, they visited museums and accumulated a mass of impressions. However, his night landscape ‘Venice’ was made six years later, on his second journey, this time travelling alone. In a letter to his wife he wrote: “Venice is a city with which one could fall madly in love. Saint Mark’s Square and Cathedral on its own, the Doge’s Palace too - every time a whole range of new impressions. Venice is beautiful in the morning, in the daytime, and in the evening. Yesterday there was some big festival here, there were masses of people, ancient flags, gondolas with elegant gondoliers - they all passed the palace, and it sparkled in the sun!” Take a look at this painting featuring the night sky. It is painted with bold, free, dynamic brushstrokes, and brightly illuminated by the fireworks. The fire rises up first, before it falls into the water in a glitter of rain. Multi-coloured Chinese lanterns, the gondolas and the whole expanse of water – all is filled with the vibrating effects of different colours. We don’t see figures, instead we feel the visions of people - we see no boats, only flickering brushstrokes. This work was showcased at the Kustodiev’s posthumous exhibition in 1968 - the biggest exhibition of his work ever, held in the museum of the Academy of Fine Arts. At that time the painting was owned by a private collector, and after that show it was taken abroad. It was first exhibited in Russia only in 2013.

Post link

Pyotr Konchalovsky. Various Flowers (Still-life with flowers and watering can).

1939. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

“You cannot paint a flower ‘just like that’, in slapdash strokes - it needs as much study as anything else. Flowers are great teachers for artists, since discerning and comprehending the structure of a rose requires no less effort than deciphering that of a human face. Painting flowers for me is what practicing scales is for a musician: after a couple of hours’ work your brain goes into overdrive and instead of flowers, sounds crop up… It is a massive exercise for a painter.” Konchalovsky spoke of flower still-lifes with expertise and vigour; it was therefore, perhaps, no surprise, that towards the end of his life he was accused of ignoring the everyday life around him, and of only caring for his art. “At the moment I am much taken with painting ‘against the sun’, – he told his friend, the art critic Viktor Nikolsky in the early 1930s, – “I am interested in catching its hurling silver at the leaves, the trees, at everything – a rather cold kind of silver in so many hues… and such gliding light over the foliage.” Konchalovsky settled far from Moscow, in a place called Bugry near the town of Maloyaroslavets, where he tended his garden, made honey, bred pigs and smoked gammon. Following such a traditional way of life, he did not welcome the comforts of civilisation: there was no electricity in the house, only oil lamps, and the radio was always switched off to shut out news of the outside world.

Post link

Marc Chagall. A wheatfield on a summer’s afternoon.

1942. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Post link

Mikhail Shemyakin. Girl in a Sailor Suit (Sonechka).

1910. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

Sonechka… The name of Mikhail Shemyakin’s young model is the only thing that researchers have been able to discover about the girl. We’re left to guess who she was, and to enjoy the beautiful technique of her portrait – “Girl in a Sailor Suit".

Look for a moment at the background - it’s almost impossible to understand just where she may be sitting. The background was executed in wide strokes, while the image of the young girl herself was clearly created with slower, softer and more tender brushstrokes, with both rapture and delight. The composition is unusual, built around a diagonal, and the light forward tilt of the head was a favorite touch of the artist. The bold and generous reflections of light on the girl’s face, and the collar and cuffs of her sailor suit are called “overtones” and emphasize the heroine’s vivacity. “His paintings are filled with grace, rhythm and subtlety, he seeks to grasp man’s nature and inner life with just a few strokes, and is perfectly precise in approaching but never crossing the fine line between artistic creation and a piece of craft” – such was the high opinion of one art critic about Shemyakin. The artist favored portraiture over all other genres, rather like his teacher Valentin Serov. He excelled in it, and received well deserved recognition from Igor Grabar, the renowned Russian painter, art historian and critic: “A new powerful master of portraiture, a highly professional artist has emerged on the Russian artistic scene. Shemyakin’s portraits have always been skillfully drawn, well composed and are outstanding with their strong sense of character!” Shemyakin portrayed many famous people of his time, such as Vladimir Filatov, the Russian-Ukrainian ophthalmologist and surgeon, and the Russian botanist and physiologist Kliment Timiryazev. But musicians were far and away his favourite subject, earning him the “high nickname” from Igor Grabar – “Painter for the Musicians”. Vladimir Mayakovsky, who was also educated in the arts, called Shemyakin a “realist-impressionist-cubist”. Shemyakin inherited his recognizable “wide manner” of painting from his teachers Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin, and it would later be recognized as one of the main features of Russian fine art of the late 19th century.

Post link

Isaak Brodskiy. Vladimir Lenin at the Rally of Putilov Plant Workers in May 1917.

1929. State Historical Museum, Moscow.

In February 1917 strikes at the factory contributed to setting in motion the chain of events which led to the February Revolution. In 10 March 1919 at protest rally in the factory striking workers condemned the Bolshevik government in a resolution claiming “…the Bolshevik government is not the authority of the proletariat and peasants, but the authority of the dictatorship of the Central Committee of the Communist Party…”. When Lenin came to Petrograd to give a speech on 13 March the workers demanded his resignation and when Zinoviev tried to address the workers he was greeted with shouts: “Down with the Jew!”. Strikers barricaded themselves in the factory which was stormed by the Cheka to suppress the strike and about 200 workers were executed.

After the October Revolution it was renamed Red Putilovite Plant (zavod Krasny Putilovets), famous for its manufacture of the first Soviet tractors, Fordzon-Putilovets, based on the Fordson tractor. The Putilov Plant was famous because of its revolutionary traditions. In the wake of Sergey Kirov’s 1934 assassination, the plant was renamed Kirov Factory No. 100.

You may find more information about the factory here.

Post link

Aleksandr Benois. Chinese pavilion. Jealous husband.

1906. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Benua, confined within the limits of his retrospective view of history, believed that the ages and style do not come one after the other, but are unique and closed within them. Rococo with its enthusiasm for things Chinese, Oriental ornamentalism, was similar to the style of Art Nouveau, of the time of Benua. The image of Rococo, the most refined and exquisite style of the 18th century, beloved by the artists of The World of Art, is embodied, according to Benua, in the shapes of outlandish Chinese pavilion, which resembles a light burning in darkness. This fragile island of light is lost between two abysses: a dark starry sky and its reflection in water. The instability of the vision is emphasized by the comic fussing of the characters, dolly ladies and gentlemen, resembling a Chinese shadow show. The style of Rococo, like a bright flash, glared up on the horizon of European culture and has long been extinguished, with a mere flicker remaining.

Post link

Mykola Samokysh. Courage Of General Raevsky.

1912. Museum-Panorama the Battle of Borodino, Moscow.

July 23, 1812 the battle of Saltanovka, which has become one of the most legendary pages of the life of General Raevsky. This feat glorified General in the nation. Then arose a legend which was reflected in the famous painting — Rajewski goes on the attack, and next to him are his sons, 17-year-old Alexander and 11-year-old Nicholas.The General himself said it was just a legend. The sons were, indeed, in his case, but in attack they did not go. But in people’s memory Raevsky was a man who sacrifices for the homeland the most expensive.

Post link

Viktor Vasnetsov. Duel Peresvet With Chelubey.

1914. Samara Regional Art Museum, Samara.

Alexander Peresvet, also spelled Peresviet, was a Russian Orthodox Christian monk who fought in a single combat with the Tatar champion Temir-murza (known in most Russian sources as Chelubeyor Cheli-bey) at the opening of the Battle of Kulikovo (8 September 1380). The champions killed each other in the first run, though according to a Russian legend, Peresvet did not fall from the saddle, while Temir-murza did. Peresvet’s body, together with that of his brother-in-arms Oslyabya, were brought to Moscow, where they lie buried at the 15th-century Theotokos Church in Simonovo.

Post link

Anton Lavinsky. Poster for Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

1925. Chrome lithograph. Production of the 3rd Factory of Goskino. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

Poster for the film ‘The Battleship Potemkin’, 1926, directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Sergei Eisenstein was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. 'The Battleship Potemkin' presents a dramatized version of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkinrebelled against their officers.

The Russian battleship Potemkin was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet. It became famous when the crew rebelled against the officers in June 1905 (during that year’s revolution), which is now viewed as a first step towards the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Post link

Valentin Serov. Peter I The Great.

1907. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Peter I, or Peter the Great (1672-1725), was one of the most outstanding rulers and reformers in Russian history. He was at first a joint ruler with his weak and sickly half-brother, Ivan V, and his sister, Sophia. In 1696 he became a sole ruler. Peter I was Tsar of Russia and became Emperor in 1721. As a child, he loved military games and enjoyed carpentry, blacksmithing and printing.

Peter I is famous for carrying out a policy of ‘westernization’and drawing Russia further to the East that transformed Russia into a major European power. Having travelled much in Western Europe, Peter tried to carry western customs and habits to Russia. He introduced western technology and completely changed the Russian government, increasing the power of the monarch and reducing the power of the boyars and the church. He reorganized Russian army along Western lines.

He also transferred the capital to St. Petersburg, building the new capital to the pattern of European cities.

In foreign policy, Peter dreamt of making Russia a maritime power. To get access to the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Azov Sea and the Baltic, he waged wars with the Ottoman Empire (1695—1696), the Great Northern War with Sweden (1700-1721), and a war with Persia(1722-1723). He managed to get the shores of the Baltic and the Caspian Sea.

In his day, Peter I was regarded as a strong and brutal ruler. He faced much opposition to his reforms, but suppressed any and all rebellion against his power. The rebellion of streltsy, the old Russian army, took place in 1698 and was headed by his half-sister Sophia. The greatest civilian uprising of Peter’s reign, the Bulavin Rebellion (1707—1709) started as a Cossack war. Both rebellions aimed at overthrowing Peter and were followed by repressions.

Peter I played a great part in Russian history. After his death, Russia was much more secure and progressive than it had been before his reign.

Post link

Stanislav Zhukovsky. Interior of a Room.

1910-20s. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

Apparently, this painting of Stanislav Zhukovsky was inspired by memories of his distant childhood. The son of a Russian aristocrat who had lost his family estate, the artist often addressed the theme of the ancestral estates of the nobility, with their spacious rooms, elegant decor, and parks. “I’m a great fan of antiquities, and, in particular, of Pushkin’s epoch …” – Zhukovsky used to say about himself. And this interior is a return to the past, too. The room is filled with life, light and air - every object, whether vase, chair or portrait, seems to convey an emotion of its own. And what an idyllic vista opens up outside the window! However, Stanislav Zhukovsky would pay a bitter price for his passion for the old. He was a popular artist and a participant in the best exhibitions, but after the Revolution all of a sudden, he became an “enemy of the Proletariat”. The press called this poet of the past noble era “a living corpse”. His art was compared to a ‘street fairy, or a faded beauty with a rouge on her cheeks and bright lips’. No surprise then that the artist decided to leave for Poland, his historical homeland.

Post link

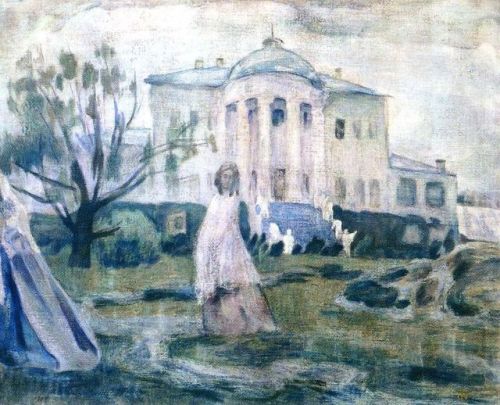

Viktor Borisov-Musatov. Ghosts.

1903. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

The image of the world in the picture is represented using a fine, semi-transparent veil, which seems to conceal strange light. Phantom figures, generating numerous reflections in the wave-like fluctuations of space, glide away like echoes of music that is dying in the distance. By placing the figures in no particular order, the artist creates an impression of their spontaneous movement, as if they were driven by some unknown force pushing them. The image instability is achieved using the technique of reduced dull tempera to produce fresco-like radiance. The picture seems to comprise quite a few transparent layers. The colours do not obscure the view of the underlying fabric of coarse-grained canvas, which produces the effect of material half decomposed with time. The painting becomes so immaterial that it comes close to poetry and music.

Post link

Anatoly Shepelyuk. M.I. Kutuzov at the command post on the day of the Battle of Borodino. (Left)

1951.

Vasily Vereshchagin. Napoleon Near Borodino. (Right)

1897. Museum of Patriotic War of 1812, Moscow.

TheFrench invasion of Russia, known in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812, and in France as the Russian Campaign, began on 24 June 1812 when Napoleon’s Grande Armée crossed the Neman River in an attempt to engage and defeat the Russian army. Napoleon hoped to compel Tsar Alexander I of Russia to cease trading with British merchants through proxies in an effort to pressure the United Kingdom to sue for peace. The official political aim of the campaign was to liberate Poland from the threat of Russia.

The campaign was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. The reputation of Napoleon was severely shaken, and French hegemony in Europe was dramatically weakened. The Grande Armée, made up of French and allied invasion forces, was reduced to a fraction of its initial strength. These events triggered a major shift in European politics. France’s ally Prussia, soon followed by Austria, broke their imposed alliance with France and switched sides. This triggered the War of the Sixth Coalition.

TheBattle of Borodino was a battle fought on 7 September 1812. Although the Battle of Borodino can be seen as a victory for Napoleon, some scholars and contemporaries described Borodino as a Pyrrhic victory for the French, which would ultimately cost Napoleon the war and his crown, although at the time none of this was apparent to either side.

This victory ultimately cost Napoleon his army, as it allowed the French emperor to believe that the campaign was winnable, exhausting his forces as he went on to Moscow to await a surrender that would never come. The Borodino victory allowed Napoleon to move on to Moscow, where — even allowing for the arrival of reinforcements — the French Army only possessed a maximum of 95,000 men, who would be ill-equipped to win a battle due to a lack of supplies and ammunition. The Grande Armée suffered 66% of its casualties by the time of the Moscow retreat; snow, starvation, and typhus ensured that only 23,000 men crossed the Russian border alive. Furthermore, while the Russian army suffered heavy casualties in the battle, they had fully recovered by the time of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow; they immediately began to interfere with the French withdrawal, costing Napoleon much of his surviving army.

Post link