#thomas gainsborough

Thomas Gainsborough,Six Studies of a Cat, c. 1763 - c. 1769

black and white chalks, on brown paper,, h 332mm × w 459mm

Post link

One of my favorite things about Thomas Gainsborough’s portraits is the way they show how awkward and uncomfortable it was to sit in enormous side-hoops! They may have looked rather regal when a woman was standing, but the moment she sat down she became a giant satin and lace mushroom cloud.

Post link

One of my favourite paintings of all time. Giovanna Baccelli painted by Thomas Gainsborough 1782.

Post link

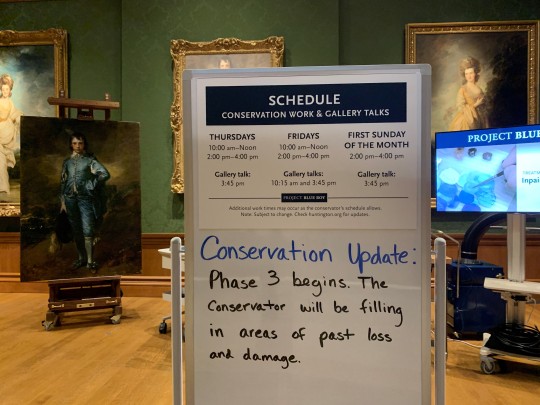

After a stay in the conservation lab for some delicate repairs to the painting’s canvas lining, Phase 2 of #ProjectBlueBoy is complete! Here’s a closer look at some of the treatments Blue Boy underwent:

To repair the torn and fragile areas of the tacking edges of the canvas, conservator Christina O’Connell carefully realigned the tiny frayed and torn threads. This type of thread by thread mend honors the original structure of the canvas.

To reattach portions where the original canvas was separating from the support lining, O’Connell added adhesive between the layers. Work was also done to repair cracks and splits found in the wooden stretcher.

Before moving back into the gallery, O’Connell took photographs of Blue Boy, as written and photographic documentation are an important part of the conservation process.

Next up: Inpainting in the gallery! O’Connell will be reintegrating areas of past loss and damage to the painting during Phase 3. For more details on the project and to see the in-gallery conservation schedule, check out huntington.org/projectblueboy.

ca. 1773 Lady by Thomas Gainsborough (Christie’s - 29Oct18 auction Lot 61). Blurred image to remove pervasive cracks w P'shop 3334X4059 @150 1.8Mj. The image was less blurred at eyes, eyelids, lips, pearls/beads, and gold trim.

Post link

Aria et 6 variations en sol mineur, P. 196 : II. Variation 1 – Johann Pachelbel

Détail de « Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott », par Thomas Gainsborough (1778).

Detail of “Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott”, by Thomas Gainsborough (1778).

Post link

Thomas Gainsborough,Portrait of Mary, Countess of Howe, wife of Admiral Richard Howe

1764, oil on canvas, 244 x 152.4 cm, Kenwood House, London (closed for renovations until autumn 2013)

Post link

Thomas Gainsborough,Anne Ford (later Mrs. Philip Thicknesse)

1760, oil on canvas, 197.2 x 134.9 cm, Cincinnati Art Museum

Post link

Thomas Gainsborough (1727 - 1788) - Portrait of Lady Catherine Ponsonby, Duchess of St. Albans

Post link

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

“The Honourable Mrs Graham” (1775-1777)

Oil on canvas

Rococo

Located in the Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland

“The Blue Boy”, Thomas Gainsborough, ca. 1770.

This is an 18th century portrait of 17th century fashion and I LOVE that.

It is thought to be the portrait of Jonathan Buttall, but this is not 100% confirmed information, but we can say that this Jonathan guy owned the painting since its creation until he filed for bankruptcy in 1796.

Apparently Gainsborough decided on this subject to “challenge” Reynolds and his theory that it would be awful to have a painting with a warm background and a cold lighted subject. Of course he was wrong, but we have already talked about Reynolds’ love for red.

The idea of the 17th century fashion came from the Van Dyck portrait of Charles II (well, who doesn’t love the bows and lace?). From my side, I totally LOVE the open sleeves of his little doublet and I have to say that this painting and the Versailles stills we’ve seen go perfectly together in all that blue.

THE BLUE BOY IS BACK AND I HAVEN’T THOUGHT ABOUT IT!

After 100 years (yes! It was bought in 1921), he’s back to The National Galley since last January till May 15th in Room 46.

So, everyone who can, go pay a visit to my personal favourite portrait in Van Dyke fashion. Of course, here a short video from the National Gallery talking about Gainsborough, the painting, the colour, the fashion, and one of the (several) supposed identities of The Blue Boy:

Post link

One of Georgiana’s numerous fashion achievements was her invention and popularization of what was known at the time as the Picture Hat. When she sat for Gainsborough in 1783, Georgiana wore this heavenly haberdashery, which she had designed herself. After the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the hat became all the rage. Numerous women went straight to their milliners, requesting “the picture hat” that they has seen at the Royal Academy. Whether they actually liked the over-sized feathered and ribboned black hat or were only imitating the fashionably elite is not known, but this hat resurfaced in the following century among Victorian women, now called the “Gainsborough Hat”.

Below are some pictures of this fabulous hat.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/picture-hat.html

The brief history of Castrati - part two (part one)

From about 1680 the expectation, eventually the rule, was that the leading male part in a serious opera (primo uomo) should be sung by a castrato; there might be a less important secondo uomo part, also for a castrato, with tenors singing the parts of kings and old men. This was also the period when Italian opera came to be given fairly regularly both in Italy and in those parts of Europe under Italian musical influence - in the German-speaking countries and the Iberian peninsula, from about 1710 in London, from the 1730s in Sankt Petersburg. The best castratos therefore became international stars, welcomed and highly paid in all the leading courts and capital cities, with the notable exception of Paris (where, after Cardinal Mazarin’s attempts at importation in the mid-17th century, they were not allowed to appear in opera; some leading castratos gave concerts when they were passing through, and some much more modest ones remained on the king’s musical establishment as church singers until the Revolution).

The reasons for this new dominance of the castrato voice are interrelated. Italian composers of the period 1680 - 1720 began to write operas calling for more technically demanding coloratura singing; the range expected of leading singers widened, and the tessitura generally rose, as it was to go on doing (for both men and women) through most of the 18th century. Virtuoso castratos were now available in numbers in the service of princes who promoted frequent opera seasons: Giovanni Francesco Grossi (”Siface”) and Francesco Antonio Mamiliano Pistocchi were only the most prominent among a new group of star singers. It was still possible at this time for a famous castrato not to sing in opera at all, like Giovanni Battista Merola, active in Naples in the late 17th century, or, like Matteo Sassano (”Matteuccio”), whose career lasted from 1684 to 1711, to do so only occasionally. But from then on a famous castrato was in the first place an opera singer. Church choirs had increasingly to grant their best castratos leave to sing in opera.

Castratos occasionally appeared in comic opera but (outside Rome) normal voices were there the rule. In the newly refined genre of serious opera, on the other hand, the castrato voice with its special brilliance appears to have struck contemporaries as the right medium to convey nobility and heroism. Objections, when they came, were to the incongruity of castratos in general - or, on moral grounds, to their singing of womens parts - rather than to their appearance as heroes or lovers.

Post link