#academic sources

Hello! It’s been more than a month, I bet some of you forgot that you followed this blog. If all goes well- cross your fingers for me, everybody- you should see a relative flurry of activity on this blog in the near future as I catch up with my backblog. (As you can tell, I chose the subject of blends for solely dry, academic reasons. … ‘Backblog.’ Hee hee.)

Today’s source is only the second I read for my independent study, whose midterm is fast approaching. Oops. It’s Louise Pound’s 1914 work, “Blends: Their relation to English word formation.” Like the Bergström source I looked at earlier, this one is out of copyright and is available for free and legal download here.

Pound’s work doesn’t say very much that Bergström didn’t, but she says it a lot better, and leaves a lot of silly things out. Even more excitingly for my purposes, Pound’s work is entirely about morphological blends, rather than being dedicated mostly to syntactic blends. If you’re only going to read one of these two works, read Pound.

The biggest new thing in Pound is that Pound introduces a source taxonomy- a taxonomy based on who made the blend and for what purpose. Pound divides blends into the following categories:

- “Clever Literary Coinages” (e.g., galumphing, fidgitated)

- “Political Terms,” also including anything the press invents (e.g., gerrymander, Prohiblican, Popocrat)

- “Nonce Blends” (e.g., sweedlefrom swindle+ wheedle), which is how Pound categorizes error blends, although she notes that error blends that prove popular may persist in the context in which they were accidentally coined. Apparently this label only applies to erroneous adults, because the next heading is

- “Children’s Coinages” (e.g., snuddlefrom snuggle+ cuddle) which she notes as also largely accidental. (Why the split?)

- “Conscious Folk Coinages” (e.g., solemncholy,sweatspiration) and

- “Unconscious Folk Coinages” (e.g., diptherobiafrom diptheria+ hydrophobia, insinuendo), which are distinct from the conscious sort and from normal errors in that they are believed to be 'real’ words and have persisted in a wider context

- “Coined Place Names; also Coined Personal Names” (e.g., Texarkana, Maybeth)

- “Scientific Names” (e.g., chloroform, formaldehyde)

- “Names for Articles of Merchandise” (e.g., Locomobile, electrolierfrom electro- and chandelier)

She notes that some of these aren’t mutually exclusive, and suggests that the source of a blend may affect its success; however, it’s not clear which she believes would be more successful. To me, this sort of taxonomy doesn’t seem very useful. I’m more interested in a taxonomy that references more linguistic characteristics of the blends and source words, but Pound essentially throws her hands up in defeat at taxonomizing blends in this way. Blends are too varied, she argues, for a “definite grouping [to seem] advisable.]”

She does mention that, as a hard rule, the primary stress in a blend is on one of the primarily stressed syllables from the source words, and she mentions haplology, which she describes as the deletion of one of two (or possibly more) similar syllables in sequence. A blend she describes as haplologic is swellegant, from swell+ elegant. The sequence /ɛl/, pronounced like the letter L, that would be repeated if you just said swell-elegant, is preserved only once. I wouldn’t necessarily describe the /ɛl/ in elegant as a syllable- I’d say that the /l/ starts the next syllable. In fact, many of the haplologic blends she describes delete similar sequences, and not properly syllables. Does this matter? You’re free to discuss among yourselves.

Pound, like Bergström, brings up onomatopoetic blends, and doesn’t conclusively place them in or out of the category of blends. I tend to say 'out’. Onomatopoetic 'blends’ generally have as their sources one of two classes of words that have sounds and maybe a general meaning in common and combines those sounds together; for instance, chump (with the original meaning 'a short segment of wood’) is suggested to have arisen from chop, chunk, or chuband lump (but equally plausible, and having similar meanings, are bumpand hump).

With no definite single-word source for either element, it seems more likely that a word like this arose from non-word, non-morpheme (it’s not like you can add -ump onto anything and make words referring to small, smooth raised areas on a surface) associations people have with certain sounds or sequences, so that words made 'out of the blue’ have suggestive forms. This, or ideas like it, is called sound symbolism- the apparent meaning individual sounds sometimes appear to have when the sounds themselves don’t behave like morphemes.

That’s about it for Pound (1914)- next up is MacKay (1972, 1973), a jump of nearly sixty years!

I hope you were not misled by my last posting; most of this blog is going to be me explicating and responding to scholarship on blends, and not fun examples of blends in pop culture, although I’ll try to post any of those I find! I do hope, however, to keep these posts as digestible and accessible as possible.

Today’s post concerns the chronologically earliest source I found in my initial research, “On blendings of synonymous or cognate expressions in English,” a 1906 dissertation by one Gustav Adolf Bergström, which is out of copyright- you can download it freely and legally here. (By the way, you will find a full citation of any academic source I mention here on the References page, which can be found on the sidebar of my blog.)

This text has a couple of issues. One, it’s one of the worst-organized pieces of scholarship I’ve ever read- sorry, Gustav. (In his defense, he says in his preface that his work got derailed by illness, which I totally get.) Two, Gustav considers the primary focus of his work to be what he calls ‘syntactic blending,’ where a speaker appears to have started saying one sentence or phrase and then meandered into another, and while he considers lexical blends to be related it’s a secondary focus of the work.

I don’t like this idea that 'syntactic blends’ are related to morphological blends at all! Current theories of linguistics that I’m familiar with say that there is a two-way split, roughly, in the representation of language in the mind. On the one hand there’s the lexicon, which is like a mental dictionary that stores everything you know about all the words you know- their form(s), like the fact that to be has the present-tense indicative forms am,is, and are, their syntactic category, such as verb, noun, adjective, etc., and their meaning, although it’s controversial exactly how much information about a word’s meaning is stored in the lexicon. On the other hand there’s the syntactic component, which strings words together according to certain rules. (You can go into finer detail about how the syntactic component is divided, but I won’t here.)

The point being, words are stored in the lexicon, but phrases and sentences are built in the syntactic component from words in the lexicon, and not 'stored’ in the same sense as words are stored (with the exception of idioms, phrases or sentences whose meanings are memorized rather than being possible to figure out just from the words they’re made up of- for instance, letting the cat out of the bag means 'telling a secret,’ which isn’t obvious at first glance and which language learners have to memorize). So words and phrases/sentences are very different things, structurally- one memorized, one constructed on the fly.

Bergström’s theory about how error blends, blends formed on accident as a speech error, are formed is that the speaker considers two related words at once for a given thought and tries to articulate both- or, more precisely, switches over at some point from saying one word to trying to say the other. As far as psycholinguistic theories from before the cognitive revolution go, this isn’t bad! It’s hard to say, though, that the same process applies to 'syntactic blendings’ when our theories say that phrases aren’t stored in the brain in the same way that words are- even if people do consider two different phrases at once and accidentally switch between them, they’re constructing them in the moment instead of simply remembering them.

Since I’m studying morphological blends specifically, and I don’t agree that 'syntactic blendings’ are another instance of the same phenomenon, I didn’t make use of the parts of the text that were about these 'syntactic blendings’.

Despite his focus not being on morphological blends specifically, he does have some interesting insights to offer. He suggests that blends are asymmetric, that is, that the two words that contribute to a blend may contribute to it in different ways. While he doesn’t go into much detail about how their roles may differ, this basic insight will, as we’ll see later in the semester, be borne out by more modern research. He notes, as other researchers have, that blends occur in many (perhaps all) languages- that is, they are cross-linguistic. And he theorizes that error blends result from pairs of words that are related in meaning through synonymy, similarity or equivalence of meaning, or antonymy, opposition of meaning. Intentional blends, which are what they sound like- blends made on purpose- he suggests are in imitation of naturally-occurring error blends, and don’t have to be synonyms or antonyms like error blends do. He specifically mentions that two words that are frequently right next to each other may be blended intentionally, such as GritainfromGreat+Britain.

He notes that some blends seem 'better’ than others, a concept for which I often use the term felicity- literally meaning 'happiness’ or the quality of being pleasing. This is a difficult-to-define concept, but basically it means how 'successful’ a linguistic form is in some measurable way- how easy it is to understand, how likely it is to be adopted into the mainstream, or simply how much speakers prefer it to other, similar forms. I did a pilot study a while back on what factors make unfamiliar blends more easily intelligible to speakers, which I might make the subject of another post.

The qualities that Bergström suggests may influence the 'success’ of a blend include usefulness (does the new form encapsulate some common concept that is otherwise complicated to express?), whether the blend fits the 'character’ of the language (which I’d translate into, does it sound like other commonly-used words?), and the frequency of the parent words separately and together.

It is because of lack of this 'success’ in making it into the mainstream that blends are such a comparatively rare source for new words in the general knowledge; he suggests that blends are invented all the time, but rarely make it out of the small circle in which they were innovated, so that they die out almost as fast as they’re invented.

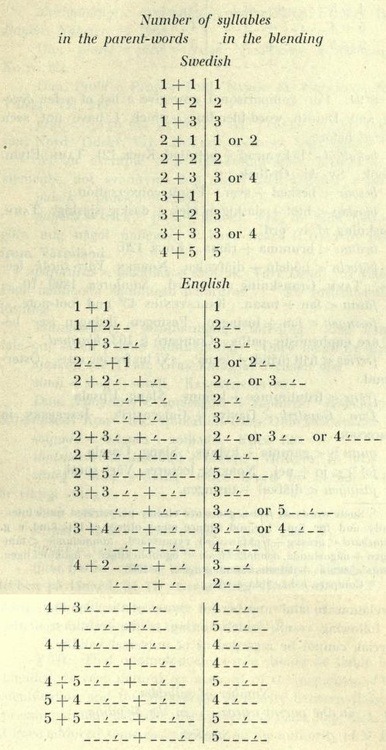

Bergström also notes some commonalities in form among blends- that they preserve stress on one of the stressed vowels in the parent words. For instance, in the blend Brangelina, it's Brangelina, and not Brangelinaor Brangelina; it takes its stress from the source word Angelina. He further notes that both beginnings of words are rarely preserved, but does not note that, to my knowledge, it is never the case that neither beginning is kept. Finally, he makes a chart that I’d be better off inserting as an image than trying to describe:

Fig. 1: Bergström takes the blends he has available and compares the syllable number and stress position of the parent words to the syllable number and stress position of the blend. In the English chart, each underscore represents a syllable and the tick mark represents the syllable that takes primary stress.

Finally, Bergström divides blends up in several ways- that is, he forms a taxonomy, or a system that divides things (here, blends) into groups based on characteristics they all share. The first major taxonomy he introduces is three-way: 'subtractive compromises,’ where both parent words lose material in the blend, like brunch; 'partial subtraction compromises,’ where one word is preserved but the other loses material, like slithy; and 'addition compromises’, where neither parent word loses material. For the last category, he uses the example forbecause, which just sounds to me like a compound; for my purposes, I’d say this would apply to a word like slanguage.

He additionally divides blends into one category that switches from one word to the other only once- like brunch, where br- is from breakfast and then it switches to -unchfromlunch- and another category that switches between the words more than once- like slithy, with the sl- from slimy, -lith- from lithe, and the -yfromslimy once more.

The last division Bergström makes is between error blends and intentional blends, which we’ve talked about already, and onomatopoeia blends. Onomatopoeia are 'sound-imitative’ words like bangandclick, and frequently words of this type that mean similar things have similar sounds in them. Here Bergström classifies some of these as blends, as will the next source I examine- Pound (1914)- but I incline towards a different analysis which I will expand on after writing about that source.

Whew! That’s a lot of words! Buckle your seatbelts, kiddoes, because posts like this are gonna make up the meat of this blog.