#arnold schoenberg

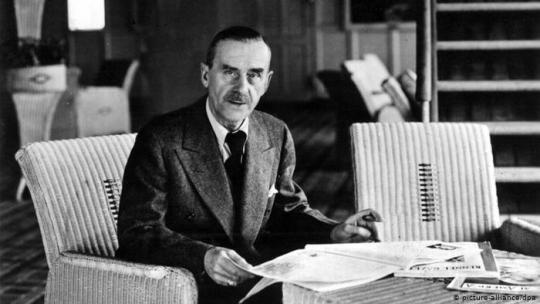

Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn as Told by a Friend, dates from Mann’s time as a German expat, living in Southern California. Indeed, Mann was one of the leading figures in the large German expat community that grew up in Hollywood, beginning in the late 1920s. Having just re-read the novel, for the first time in 40 years, in a new translation by John E. Woods, I am struck by the combination of love for and dismay with German culture Mann’s narrator displays. [Spoiler alert: I’m going to be talking about plot details here, so if you plan on reading this book someday, maybe stop reading now.]

I’ve long been a fan of so-called meta-fiction, in which an author writes a book that is as much about the act of writing as it is about the supposed content of the book. So although Doctor Faustus is ostensibly about the life of a composer, one might see it as a work about any creative figure, and given the self-consciousness of the narrator, a man attempting to write a biography about a friend that he clearly idolized, Mann has created a classic example of the unreliable narrator for us. When the narrator asserts “I am not writing a novel here,” or notes “If I were writing a novel…” one cannot help but think, “Ah, Herr Mann, but you are writing a novel, aren’t you?” And indeed, the act of writing, the difficulty of writing, is very much a part of the subject, so much so that our narrator occasionally completely loses track of his topic, and spends many pages going on about the difficulty of accomplishing any kind of writing in a Germany that is engaged in the end-game of World War II. Indeed, I will go so far as to assert that the Faustian “bargain with the devil” that is at the core of this text is really the strange, compromised relationship between the author and the country has both loves and despises.

The book demonstrates a slippery relationship between fiction and reality. So, for example, the main character of Adrian Leverkühn, spends many years of his life, living in a tiny rural community a short train-ride away from Munich, in a town called Pfeiffering (”whistling”). Of course, there is no such town to be found in Bavaria. From the narration, it ought to be about midway between Munich and Oberammergau, but it simply doesn’t exist. Similarly, other locations that are described as real in the text simply are not real. At the same time, actual historical personages are dropped into the tale. So when Leverkühn travels to Switzerland for a performance of one of his compositions, the conductor is Paul Sacher, who was indeed active as a conductor and commissioner of new music in Switzerland. This adds to the meta-fictional ambience of the work, because while the orchestra and conductor might be real, the soloist performing in Leverkühn’s work is a fabrication.

Oh, and that soloist brings up another wrinkle. Leverkühn seems to me to be homosexual. The narrator, who loves Adrian as a life-long friend, does not seem to catch this in his “affect,” but many of his personality quirks suggest it to me. He has one unfortunate experience with a prostitute, but the rest of his important relationships seem to be with other men. In particular, his relationship with a young, attractive, flirtatious violinist is described in such sexual terms that it is hard not to assume the part of Leverkühn’s devilish bargain has to do with his sexuality. I also wonder why none of the doctors who examine him seem to be able to diagnose him as having syphilis, when that is clearly what he’s suffering from. Well, that and a narcissistic personality disorder.

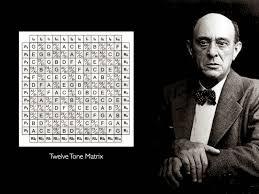

Mann felt the need to provide an apology at the end of the book, because in Chapter 22, his main character outlines a method of composing music that is unmistakably the so-called 12-tone method of Arnold Schoenberg. Considering that Schoenberg’s technique, and his Theory of Harmony, were “borrowed” for the novel, it is interesting that Mann then apologizes for attributing to Adrian something that is “the intellectual property” of someone else. When Schoenberg learned that Mann had done this, before the novel was published, he supposedly complained, “If he had just asked me, I would have been glad to come up with another method for his fictional composer to use.” But considering the mystical, mysterious, mathematical qualities that Schoenberg’s method contained, it’s perhaps understandable why Mann might want to borrow the ideas for his novel about a composer who sells his soul to the devil. Particularly, the Schoenbergian use of so-called “magic squares” - something that had been in use since the Middle Ages - must have seemed to shimmer with occult possibility.

Alas, when writers try to describe musical works and methods, they invariable flub things to greater or lesser degree. While Chapter 22 does indeed give a reasonable explanation of how Schoenberg’s 12-tone method creates musical unity in a work, other musical references go astray. One passage talks about how harmony works, in the context of what is called modulation - changing from one key to another - and he speaks of how, in the key of A, the A must resolve to a G#. In point of fact, exactly the opposite is the case: tonality’s sense of direction is driven, in part, by the need to move the so-called “leading tone” upward to the tonic. So it is G#’s push upward to A that fuels the engine of A major, not the other way around. In another spot, there is mention of Debussy’s sonata for flute, violin and harp, which would be fine, except that the work uses a viola, not a violin.

The novel’s narrator, Dr. Serenus Zeitblum, plays the “viola d’amore,” and this is mentioned a number of times. While I can understand the symbolic importance of this (the narrator plays the “viola of love” and spends all his time pining for his beloved friend Adrian?) (i.e. the entire novel as a song played on the viola of love?), at the time period in question, this would have been an extremely obscure instrument for someone to learn. So the fact that Zeitblum plays this obscure, 18th-century instrument seems to be part of Mann’s strategy to deeply brand the narrator as a pedant. Zeitblum makes fun of himself for his job as a teacher of classics, not as a creative artist like his friend.

Having fought my way through Mann’s Magic Mountain years ago, I have to note that Mann loves to hear himself talk. It is not unusual for page after page after page to go by, while the characters speculate about philosophy or politics or the arts, and not much happens. And then, as the book gets closer to its conclusion, there is a flurry of activity that unfolds in a hurry, as though Mann suddenly remembered that a novel is supposed to have a plot, and he hasn’t really been providing one for a long time. Doctor Faustus has a similar arch: most of the action, including a a suicide, a murder, the horrible death of a child, and the complete mental breakdown of the main character, all occur in the final quarter of the novel.

So then, what is this novel really about? A novel about novels? A modern updating of a medieval tale? An examination about the curious place of music in contemporary culture? I think the book is about how German culture, for all of its lofty, idealistic peaks, sold its soul to the devil of fascism in the period between the two World Wars. In return for some remarkable creative growth and power, the country’s creative individuals had to make a bargain with an ideology of horror. Indeed, the composer that I feel has the most in common with Adrian Leverkühn is not Arnold Schoenberg, but Richard Strauss, who found himself Hitler’s leader of music for the Third Reich. When the war ended, and American troupes arrived at Strauss’s country estate, Strauss invited them in, showed them around, and acted like nothing unusual had been happening for the last five or six years. After all, it was just music, after all, and some of his best friends were Jewish…