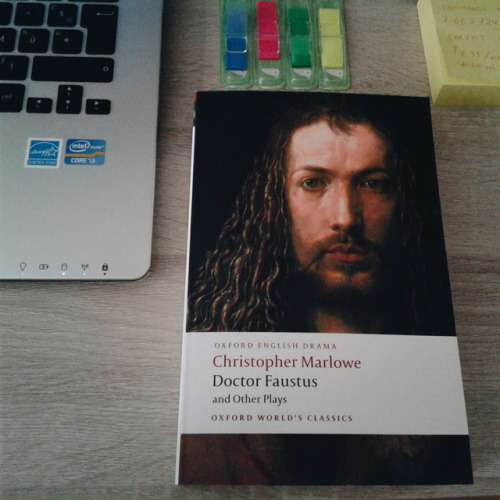

#doctor faustus

TCM STAR OF THE MONTH: ELIZABETH TAYLOR - 3/12-3/16

TCM tribute traces her remarkable career through four decades and 30 films: Cynthia - A Date with Judy - National Velvet - Life with Father - Little Women - Lassie Come Home - Courage of Lassie - Conspirator - The Big Hangover - Love Is Better Than Ever - The Girl Who Had Everything - The Last Time I Saw Paris - Rhapsody - Raintree County - Giant - Ivanhoe - Beau Brummell - BUtterfield 8 - The Sandpiper - The Taming of the Shrew - Doctor Faustus - X, Y and Zee - Elizabeth Taylor: An Intimate Portrait - Cat on a Hot Tin Roof - Suddenly, Last Summer - Reflections In a Golden Eye - The Only Game In Town - Secret Ceremony

Post link

Anxiously awaiting an email from my advisor on how best to handle an issue. Finishing notes on Rousseau. Prepping to read Goethe and listening to some classics to ease the pit in my stomach.

Post link

As requested. Fanmixes inspired by variations of the Faust myth.

i can be hell’s loverboybyropeofpearls on livejournal: A Faustus/Mephistopheles mix inspired by the recent stage production of Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus at the Globe. (01. Neil Finn - Sinner / 02. Our Lady Peace - Angels/Losing/Sleep / 03. The Bravery - Bad Sun / 04. Neon Trees - Animal / 05. Sia - Electric Bird / 06. Bats for Lashes - Daniel / 07. Yeah Yeah Yeahs - Warrior / 08. The Smiths - Handsome Devil / 09. The Sundays - Can’t Be Sure / 10. Kate Nash - Nicest Thing / 11. The Dresden Dolls - Backstabber / 12. Rufus Wainwright - Slideshow / 13. Brandon Flowers - Crossfire / 14. Amanda Palmer - I Will Follow You Into the Dark / 15. Empires - Damn Things Over / 16. The Academy is… - We’ve Got a Big Mess on Our Hands / 17. Adele - Set Fire to the Rain / 18. Aimee Mann - Stupid Thing / 19. Fallout Boy - W.A.M.S / 20. Laura Marling - Devil’s Spoke / 21. Ellie Goulding - Under the Sheets / 22. Florence + The Machine - Howl / 23. Emilie Autumn - Misery Loves Company / 24. Tori Amos - Leather / 25. Fiona Apple - Not About Love / 26. Metric - Black Sheep / 27. Broken Social Scene - Gangbang Suicide)

Goethe’s Faust Fanmixbyamiablydebauchedsloth on tumblr/8tracks: A mix inspired by Goethe’s Faust.(01. Florence and The Machine + Seven Devils / 02. Biber - Sonata No. 5 / 03. Simon Curtis – Diablo / 04. Jack White – Love is Blindness / 05. David Usher – Black, Black Heart / 06. Mozart L’Opera Rock – Le Bien Qui Fait Mal / 07. Adam Lambert – For Your Entertainment / 08. Chris Cornell - You Know My Name / 09. Frederick Mendelssohn – Violin Concerto in E Minor OP. 64 / 10. Marilyn Manson – Sweet Dreams (Cover) / 11. Dusty Springfield – Spooky / 12. Moulin Rouge – El Tango De Roxanne / 13. Jesse Cook – Incantation / 14. Innerpartysystem – Obsession / 15. L’Elisir D’Amore – Una Furtiva Lagrima / 16. Biber - Partita for Two Violins and Basso Continuo in D Minor / OPTIONAL BONUS: Cobra Starship - Good Girls Go Bad ) (Repost)

Herr Doktor Faust, PsychiatristbyShango Polo on 8tracks: A largely instrumental Faustian mix. (01. Tom Waits - The Black Rider / 02. Van Cliburn - Prelude in C-Sharp Minor (Op. 3, No. 2) / 03. Niccolò Paganini - No.24 In A Minor / 04. Art Zoyd - Pact / 05. Vladimir Horowitz - Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor for Piano, Op. 35: III. Marche funèbre. Lento / 06. Léon Boëllmann - Toccato from Suite Gothique / 07. Halgeir Schiager -

Mutationes for one or two organs: IV. Scherzando / 08. Magdalena Kozená, Michael Freimuth - Písne K Loutne: 4. Ach Gott, wie weh tut scheiden / 09. Krzysztof Penderecki - Lacrimosa / 10. Giacinto Scelsi - Quattro Pezzi I)

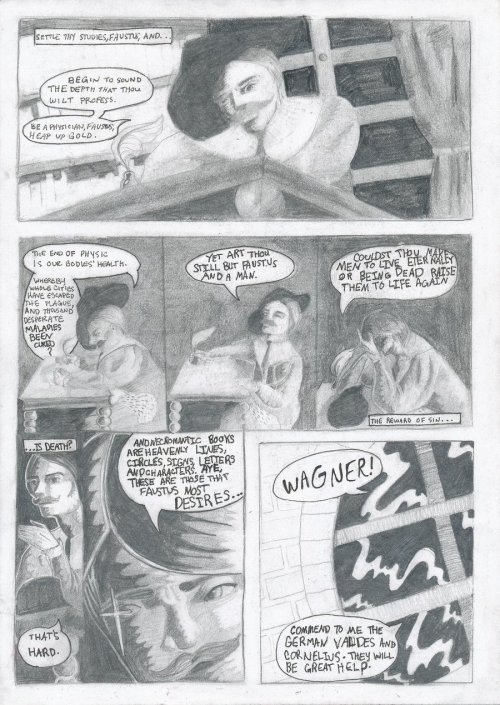

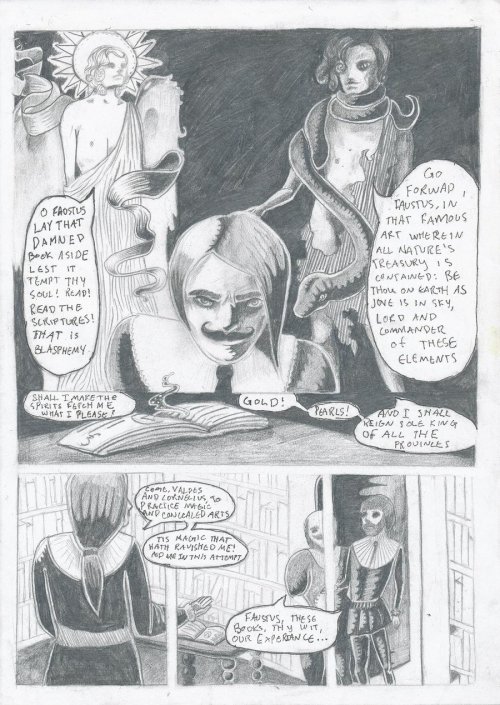

The Duality of Dr. FaustusbyDiosBoss (artist’s professional website. They also do commissions)

Post link

The Devil and Dr. Faustus, c. 1825, Wellcome Collection, London.

Doctor Faustus on stage in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse.

Paulette Randall directs a lively production of Christopher Marlowe’s moral dilemma - what would you sell your soul for?

Doctor Faustus runs in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse until 2 February 2019.

Photography by Marc Brenner

Post link

Soul Searching: Katie Hims.

We ask five of the playwrights undertaking a feminine Faustian interpretation for the Globe’s Dark Night of the Soul a series of questions about the project and their approaches.

Katie Hims is a writer and has written for both theatre and radio. She has spent time on attachment to the National Theatre Studio and has recently written Variations for National Theatre Connections 2019. She is currently working on The Stranger on the Bridge for Postcard Productions at The Tobacco Factory, Bristol. Her previous stage work includes Billy the Girl for Clean Break at Soho Theatre. Her radio work has won several awards.

Three Minutes after Midnight

by Katie Hims

A writer and her niece are waiting. While in the room next door a nurse attends to the writer’s sister. The sister is dying and the writer finds she cannot resist scribbling down a scene about her sister’s death. A scene which reveals the secret of her sister’s life. And then the writer’s niece finds the scene in a notebook and accuses the writer of selling her soul.

What made you say yes to Dark Night of the Soul?

I was completely delighted to be asked to write for Shakespeare’s Globe. I’m afraid I would have said yes to anything that Michelle Terry asked me to write! But the fact that there’s a gang of us and that to a certain degree we’re developing the material together made it very appealing. Also, I think the brief is actually very open, so we should all be able to find our own quite different stories that we’re keen to tell.

What interests you about the Faustus myth or Marlowe’sFaustus? And what are you hoping to explore with your piece?

I’m still getting my head around what the Faustian bargain might mean for a female character. Faustus is about ambition and what he will sacrifice to achieve. Traditionally men have been expected and encouraged to be ambitious and women haven’t. I’ve always felt embarrassed by the idea of my own ambition like I want to disown it. I’ve often felt like I should be pursuing something more worthwhile and less selfish. I don’t know how many male writers are plagued by this feeling. I’m sure they are out there – and of course, I might be entirely wrong – but I imagine they are greatly outnumbered by women.

And yet I really do want to write. It’s the only ambition I have. So where does that leave me when it comes to writing about the Faustian bargain? I don’t know yet… Voltaire said: “One must be possessed of the Devil to succeed in any of the arts.” There are plenty of clichés around success coming only with sacrifice and what could be a greater sacrifice than your soul?

But what is a soul anyway? It means different things to different people. We talk of writers selling their souls and it usually means writing something terrible for a lot of money. But what’s so wrong with that? Maybe nothing. Maybe it depends on the nature of what was written. But I can imagine a story in which a woman sacrifices her soul for a lot less than absolute power and all the world’s riches. Which is potentially a story about equal pay…

How do you start to write something?

It depends what I’m writing and who I’m writing for. I’m happiest when starting with a character or an incident or some other small detail, and then following the trail of where that detail leads. One of my favourite ways to begin is to overhear something someone says in the street or on the bus. When starting with a broad theme I struggle more to find my story. The canvas is so big and you don’t want the theme to be writ large across the work. Whereas if you begin small you discover your theme and you don’t need to go hunting for a story to fit.

What made you want to be a writer?

I loved writing stories as a child but it never occurred to me that a writer was something I could actually be. Then in the final year of my drama degree, we did a playwriting course and I immediately lost interest in every other element of degree because I just wanted to be writing plays all day.

How important is storytelling?

I think it’s incredibly important. I think we’re telling each other stories all the time. They’re part of our everyday lives.There is a need to tell them and a need to hear them. I’ve got the writer’s guilt about not doing something more useful with my life, but my husband says to me imagine the world without any books and plays would you want to live in that world? And of course, I wouldn’t.

Would you say that there are any themes you are particularly interested in across your work?

Lost children who somehow make it home again seem to recur again and again even when I’m actively trying not to repeat myself. I’m a fan of a happy ending if I can get away with it.

Do you like to be involved in the rehearsal process?

My absolute favourite rewrites are the ones that get done in the rehearsal room. Hearing the actors say the lines tells you everything about what’s wrong and what needs to change and what ought to be said instead. It’s urgent work and removes all the doubt and umming and aahing. But I think you can drive the actors mad if you keep changing material too far into the rehearsal process. I think I need to stay away after a certain point because I would just keep rewriting.

What’s it like seeing your work being performed?

That depends! There’s something very nerve-wracking about it. At its worst, it can be cringe-worthy; like listening to your own voice on tape. But when you are sitting among an audience who are watching a play you’ve written and they are really really laughing or crying – that’s pretty amazing, it’s probably the best bit of the whole strange business.

What’s it like to be working on a production in chorus with other writers?

We’ve spent one workshop day together and I absolutely loved it. There’s a contradiction that writing is very often an isolated process and yet storytelling demands an audience. Stories grow and get better in the telling. So during the workshop we kind of functioned as an audience for one another.

On four evenings we will perform a selection of the pieces together as Anthology Performances. Check the website to see when Katie’s response, Three Minutes after Midnight will be performed.

This interview first appeared in Globe Magazine, available to buy in the Globe Shop. Become a Member of Shakespeare’s Globe to receive the magazine three times a year.

Post link

‘Within this circle…’ Magic Circles and Doctor Faustus.

We asked our Research team to tell us a bit about magic circles and how they feature in Doctor Faustus.

Within this circle is Jehovah’s name

Forward and backward anagrammatized,

The [ab]breviated names of holy saints,

Figures of every adjunct to the heavens,

And characters of signs and erring stars,

By which the spirits are enforced to rise.

Doctor Faustus

Act 1, Scene 3

Open up a 1616 edition of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and you’ll find the play’s title figure, book in one hand, staff in another, standing within a circle, about to greet a devil who is emerging from the floor to his left. But what does this snapshot of early modern necromancy tell us about magic spells and circles?

Medieval treatises tell us that magic circles had two main functions: they boosted the powers of the conjurer, and they protected them from the unfriendly spirits that could inadvertently be called up. One fifteenth-century manuscript instructs the would-be magician to ‘sign’ or bless the circle with a magic wand, and repeat the following: ‘I make this circle in honour of the Holy Trinity […] a place of protection and refuge which the demons cannot violate, enter, defile, touch, or even fly over; they must appear in a place designated for the outside the circle’. In his Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), Reginald Scot also offers directions for such spells, instructing the conjurer to ‘make a circle’, ensuring that he ‘close again the place, there where thou wentest in’ once the mage has placed himself within it.

Not all magic circles looked the same. They could be traced on the earth, or inscribed on parchment; they could be simple or ornate in design. More often, like the one we see on the floor of Faustus’ study, these circles were made up of complex inscriptions and symbols (typically snatches of scripture or names for God) with designated positions for specific magical objects, including the conjurer him- or herself.

Amongst the names of saints and astrological symbols, the specific inscription that Faustus figures into his circle is an anagram of ‘Jehovah’, the Hebrew name for God. Inscribing this on his floor, Faustus not only flouts taboos that forbade writing the name but also mocks the belief that divine anagrams could bring mortals closer to God by using this specific inscription to conjure the devil.

Magic circles are part of the Faust story, and can be found in the German legend which Marlowe drew from. In the English translation, The History and Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus (1592), Faustus is described conjuring in a forest:

[Faustus] made with a wand a Circle in the dust, and within that many more Circles and Characters … [then] began Doctor Faustus to call for Mephistophiles the Spirite.

The circle is a space of safety, providing protection from Mephistopheles who is unable to penetrate it.

Magic circles are also part of the staging of the Faust story. One apocryphal account of a performance of Marlowe’s play at Exeter tells of one too many devils in the detail:

As a certain number of devils kept everyone his circle there, and as Faustus was busy in his magical invocations, on a sudden they were all dashed, every one harkening the other in the ear, for they were all persuaded, there was one devil too many amongst them…

Such anecdotes of extra devils appearing on stage and frightening the audience have become part of the Faustus legacy. They serve as a reminder that while Faustus might think he stands safe within the circumference of his circle while making his magic invocations, there is no guarantee that the safety extends beyond the stage…

Doctor Faustus is in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse until 2 February 2019.

Post link

Doctor Faustus in rehearsals.

What are we prepared to sacrifice in the pursuit of power?

Doctor Faustus’ mettle is severely tested in Christopher Marlowe’s moral dilemma.

Directed by Paulette Randall, Doctor Faustus opens in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on 1 December 2018.

Photography by Marc Brenner

Post link

The current state of my TBR pile - and that’s excluding PygmalionandThe Hunchback of Notre Dame on my Kobo, and Bands of Mourning on hold for me at the library. It’s gonna be a busy winter.

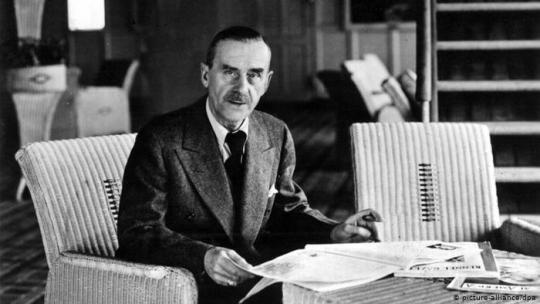

Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn as Told by a Friend, dates from Mann’s time as a German expat, living in Southern California. Indeed, Mann was one of the leading figures in the large German expat community that grew up in Hollywood, beginning in the late 1920s. Having just re-read the novel, for the first time in 40 years, in a new translation by John E. Woods, I am struck by the combination of love for and dismay with German culture Mann’s narrator displays. [Spoiler alert: I’m going to be talking about plot details here, so if you plan on reading this book someday, maybe stop reading now.]

I’ve long been a fan of so-called meta-fiction, in which an author writes a book that is as much about the act of writing as it is about the supposed content of the book. So although Doctor Faustus is ostensibly about the life of a composer, one might see it as a work about any creative figure, and given the self-consciousness of the narrator, a man attempting to write a biography about a friend that he clearly idolized, Mann has created a classic example of the unreliable narrator for us. When the narrator asserts “I am not writing a novel here,” or notes “If I were writing a novel…” one cannot help but think, “Ah, Herr Mann, but you are writing a novel, aren’t you?” And indeed, the act of writing, the difficulty of writing, is very much a part of the subject, so much so that our narrator occasionally completely loses track of his topic, and spends many pages going on about the difficulty of accomplishing any kind of writing in a Germany that is engaged in the end-game of World War II. Indeed, I will go so far as to assert that the Faustian “bargain with the devil” that is at the core of this text is really the strange, compromised relationship between the author and the country has both loves and despises.

The book demonstrates a slippery relationship between fiction and reality. So, for example, the main character of Adrian Leverkühn, spends many years of his life, living in a tiny rural community a short train-ride away from Munich, in a town called Pfeiffering (”whistling”). Of course, there is no such town to be found in Bavaria. From the narration, it ought to be about midway between Munich and Oberammergau, but it simply doesn’t exist. Similarly, other locations that are described as real in the text simply are not real. At the same time, actual historical personages are dropped into the tale. So when Leverkühn travels to Switzerland for a performance of one of his compositions, the conductor is Paul Sacher, who was indeed active as a conductor and commissioner of new music in Switzerland. This adds to the meta-fictional ambience of the work, because while the orchestra and conductor might be real, the soloist performing in Leverkühn’s work is a fabrication.

Oh, and that soloist brings up another wrinkle. Leverkühn seems to me to be homosexual. The narrator, who loves Adrian as a life-long friend, does not seem to catch this in his “affect,” but many of his personality quirks suggest it to me. He has one unfortunate experience with a prostitute, but the rest of his important relationships seem to be with other men. In particular, his relationship with a young, attractive, flirtatious violinist is described in such sexual terms that it is hard not to assume the part of Leverkühn’s devilish bargain has to do with his sexuality. I also wonder why none of the doctors who examine him seem to be able to diagnose him as having syphilis, when that is clearly what he’s suffering from. Well, that and a narcissistic personality disorder.

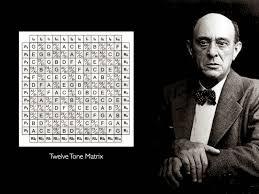

Mann felt the need to provide an apology at the end of the book, because in Chapter 22, his main character outlines a method of composing music that is unmistakably the so-called 12-tone method of Arnold Schoenberg. Considering that Schoenberg’s technique, and his Theory of Harmony, were “borrowed” for the novel, it is interesting that Mann then apologizes for attributing to Adrian something that is “the intellectual property” of someone else. When Schoenberg learned that Mann had done this, before the novel was published, he supposedly complained, “If he had just asked me, I would have been glad to come up with another method for his fictional composer to use.” But considering the mystical, mysterious, mathematical qualities that Schoenberg’s method contained, it’s perhaps understandable why Mann might want to borrow the ideas for his novel about a composer who sells his soul to the devil. Particularly, the Schoenbergian use of so-called “magic squares” - something that had been in use since the Middle Ages - must have seemed to shimmer with occult possibility.

Alas, when writers try to describe musical works and methods, they invariable flub things to greater or lesser degree. While Chapter 22 does indeed give a reasonable explanation of how Schoenberg’s 12-tone method creates musical unity in a work, other musical references go astray. One passage talks about how harmony works, in the context of what is called modulation - changing from one key to another - and he speaks of how, in the key of A, the A must resolve to a G#. In point of fact, exactly the opposite is the case: tonality’s sense of direction is driven, in part, by the need to move the so-called “leading tone” upward to the tonic. So it is G#’s push upward to A that fuels the engine of A major, not the other way around. In another spot, there is mention of Debussy’s sonata for flute, violin and harp, which would be fine, except that the work uses a viola, not a violin.

The novel’s narrator, Dr. Serenus Zeitblum, plays the “viola d’amore,” and this is mentioned a number of times. While I can understand the symbolic importance of this (the narrator plays the “viola of love” and spends all his time pining for his beloved friend Adrian?) (i.e. the entire novel as a song played on the viola of love?), at the time period in question, this would have been an extremely obscure instrument for someone to learn. So the fact that Zeitblum plays this obscure, 18th-century instrument seems to be part of Mann’s strategy to deeply brand the narrator as a pedant. Zeitblum makes fun of himself for his job as a teacher of classics, not as a creative artist like his friend.

Having fought my way through Mann’s Magic Mountain years ago, I have to note that Mann loves to hear himself talk. It is not unusual for page after page after page to go by, while the characters speculate about philosophy or politics or the arts, and not much happens. And then, as the book gets closer to its conclusion, there is a flurry of activity that unfolds in a hurry, as though Mann suddenly remembered that a novel is supposed to have a plot, and he hasn’t really been providing one for a long time. Doctor Faustus has a similar arch: most of the action, including a a suicide, a murder, the horrible death of a child, and the complete mental breakdown of the main character, all occur in the final quarter of the novel.

So then, what is this novel really about? A novel about novels? A modern updating of a medieval tale? An examination about the curious place of music in contemporary culture? I think the book is about how German culture, for all of its lofty, idealistic peaks, sold its soul to the devil of fascism in the period between the two World Wars. In return for some remarkable creative growth and power, the country’s creative individuals had to make a bargain with an ideology of horror. Indeed, the composer that I feel has the most in common with Adrian Leverkühn is not Arnold Schoenberg, but Richard Strauss, who found himself Hitler’s leader of music for the Third Reich. When the war ended, and American troupes arrived at Strauss’s country estate, Strauss invited them in, showed them around, and acted like nothing unusual had been happening for the last five or six years. After all, it was just music, after all, and some of his best friends were Jewish…

It’s Robert Schumann’s birthday today, and I’ve been thinking about Faust…