#french literature

Le petit soldat (1960) by Jean-Luc Godard

Book title:J’écoute l’Univers (1960) by Maurice Limat

Post link

Simone Weil, from The Notebooks of Simone Weil

Text ID: the dark recesses of the soul

Simone Weil, from The Notebooks of Simone Weil

Text ID: On reaching a certain degree of pain we lose the world. But afterwards comes peace, when we find it again.

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “Portrait of Dora”

Text ID: Can’t you love me a little? Just a little bit?

Simone Weil, from The Notebooks of Simone Weil

Text ID: from dissolution to becoming

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “Portrait of Dora”

Text ID: She resembles hidden, / vindictive, dangerous loves.

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “Black Sail, White Sail”

Text ID: A hundred times already I have lain in my tomb, / Perhaps I am still there now…

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “The Perjured City”

Text ID: Through blood our love and hate flow wild.

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “The Perjured City”

Text ID: We are all equal before death,

Hélène Cixous, from The Selected Plays of Hélène Cixous; “Black Sail, White Sail”

Text ID: I am what I am, may you find someone better.

Simone Weil, from The Notebooks of Simone Weil

Text ID: May the whole universe become for me a second body in both senses. / The only one attains to this by a methodical transformation of oneself.

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

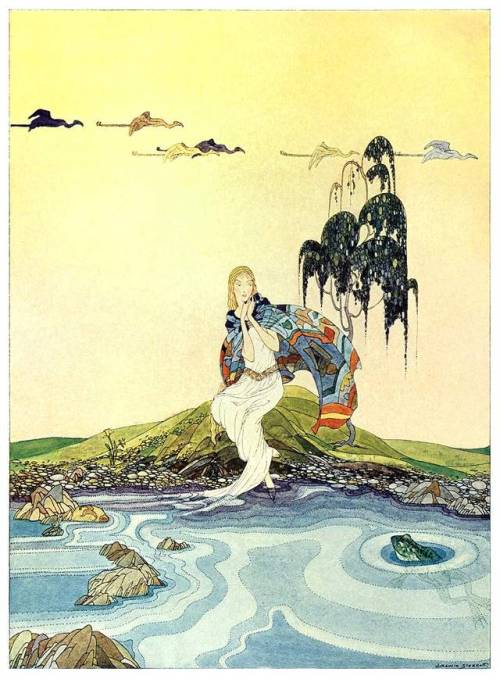

“Ah ha! You are at last in my domain, little fool!” Color process illustration by Virginia Frances Sterrett, for the book, Old French Fairy Tales, published in 1920.

Post link

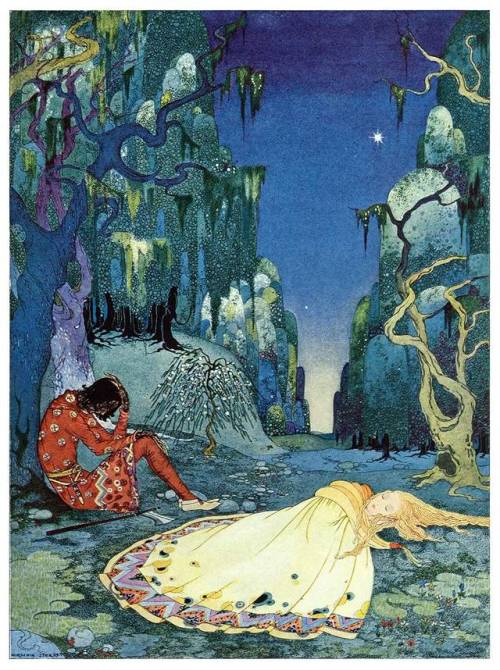

“Violette consented willingly to pass the night in the forest.” Color process illustration by Virginia Frances Sterrett for the book, Old French Fairy Tales, published about 1920.

Post link

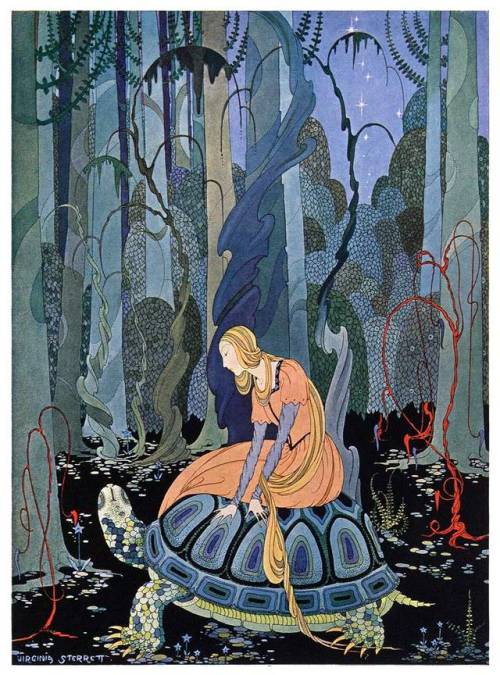

“They were three months passing through the forest.” Color process illustration by Virginia Frances Sterrett for the book, Old French Fairy Tales, published about 1920.

Post link

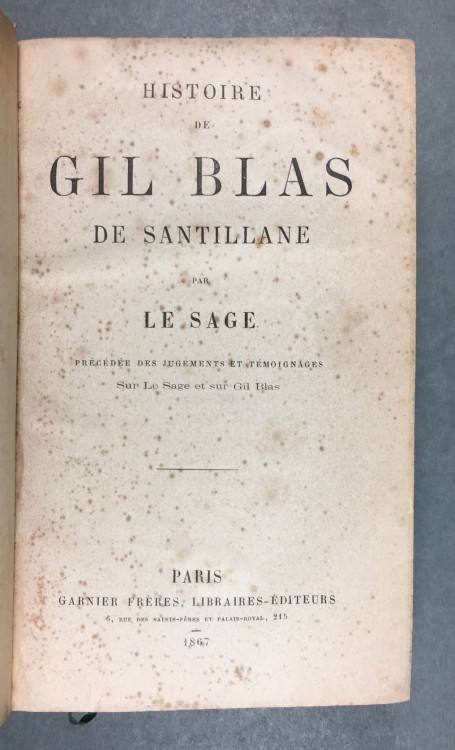

Retrospective cataloguing work recently turned up a book inscribed to the founder of our library Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull (1868-1918) when he was just sixteen.

The inscription, found in an 1867 edition of Alain-René Lesage’s picaresque novel Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane, reads:

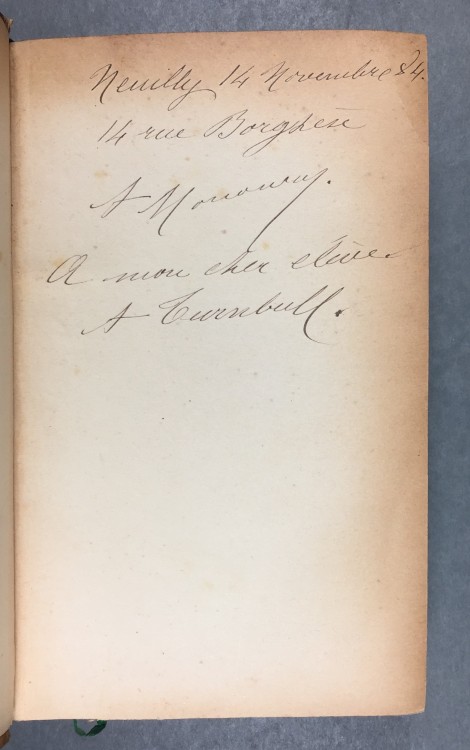

Neuilly 14 Novembre [18]84.

14 rue Borghese

A Manoury.

A mon cher élève [i.e. To my dear student]

A Turnbull.

Thanks to some detective work by Anthony Tedeschi, our Curator Rare Books and Fine Printing, the inscriber has been identified as Arthur Maximilien Manoury (1849–1900), who is listed in the 1891 Paris electoral roll as living in 14 Rue Borghese in the commune of Neuilly (officially Neuilly-sur-Seine from May 1897) in the department of Hauts-de-Seine, just west of Paris.

By November 1884, Turnbull was no longer enrolled as a student at Dulwich College, London, having left at the end of the Lent term in March. Manoury was presumably hired as a private tutor so Turnbull could continue his French education. His comprehension of the language as a student at Dulwich is described in Eric McCormick’s biography as ‘rather better than average’ (p. 59) and, while not exactly a glowing endorsement, young Alexander must have improved and impressed Manoury enough to be given such a kind gift.

This book is one of just two books from Turnbull’s youth found in the collection to date. The other volume is an 1883 edition of works by the English poet and intellectual John Milton (1608-1674).

–

Alain-René Lesage, Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane. Paris: Garnier frères, 1867, Alexander Turnbull Library, R407877.

Post link

On the docket for December are new translations of Guido Morselli’s eerily prescient tale of the last man standing after humanity disappears without a trace and André Gide’s pioneering metafiction classic, Marshlands.

Guido Morselli, Dissipatio H.G.: The Vanishing

From the author of The Communist comes this postapocalyptic novel about a man who drives down to the capital from his retreat in the mountains only to find he’s the last person left on earth. As he travels around searching for provisions and any sign of humanity, he finds that the rest of nature is flourishing.

André Gide, Marshlands

This metafictional masterpiece and send-up of writerly pretension packs a punch in its ninety-six pages. Its narrator, a social butterfly of the Parisian literati, needs everyone to know about his new novel, Marshlands, about a recluse living in a stone tower. His literary friends aren’t too impressed—and their feedback becomes as much a part of Marshlands as the novel itself.

Emily Marant in À Paris

There are many reasons as to why you should read À Paris. Not only does the book provide insight to Paris through the eyes of Jeanne Damas & Lauren Bastide, it is also a remarkable Ode to the city, celebrating the stories and lives of women in the city. It is admittedly not what most people would expect from reading it, with its goodwill and wholesome quality. Without spoiling anything, I will state how much it can change your perspective and expectations on the city of Paris. Not only will you feel like you get it, you will feel like you got keys how to experience Paris. Not to mention how Jeanne follow-up release, La Vie en Rouje does not disappoint either, we can be assured how much pleasure we take from being a part of this Histoire.

Post link

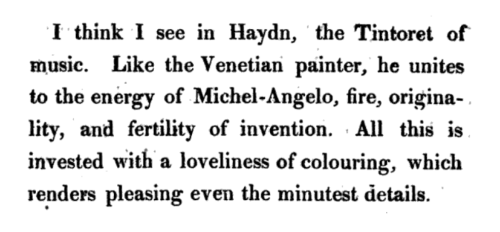

Stendhal,The Life of Haydn, in a Series of Letters Written at Vienna: Letter XX (trans. L. A. C. Bombet)

Post link

…So I was reading Phantom of the opera… I don’t know whether to despise Erik or pity him. Yes I know he killed people and kidnapped others… but-but he had a tough life… he just wanted to be normal. In the end, all he craved was normalcy and the love he’d never received.

That book was a tragedy and no one can convince me otherwise.

In any case, they wouldn’t’ be able to appease the brutal awakening in her body. It was more of a psycho-sentimental awakening that shocked her. Masturbation was not her thing. She always felt the need for physical content. And as Dominique’s body was similar to her own, it allowed her not only to rediscover herself, but also to provide her with a certain balance. This forbidden relationship was like a drug, and she knew that its sudden withdrawal would make her completely crazy.

Emilienne, the in many ways privileged protagonist of Angèle Rawiri’s The Fury and Cries of Women, has gained repute involved supporting women’s causes and a successful career eclipsing that of her husband, Joseph. But suffering and feeling a failure in her social and personal life, especially when it comes to marriage and the maternal, her future and life becomes hazy, as she both compromises on and defies the roles society, family, and herself set for her.

Today with one able to peruse the works of several Gabonese writers, this older novel, translated by Sara Hanaburgh, I chose in part for its main character. Emilienne is a defiant woman who at one point finds solace in the arms of another woman. Indeed, even the word lesbian is on the page. Though this use is not in a positive scene, negative shifts further mirrored earlier in the writing around the relationship. While Rawiri‘s last novel of three, notable for more greatly broaching several subjects, including the taboo, it is nonetheless not one where breadth or sensitivity is always reflected. A more detailed evaluation involves a long tangle of quotes and spoilers you can find here.

For a novel classed and immersed in its protagonist’s convictions around women’s issues, the varieties therein of feminism and individual meaning of such in action and conflict, the writing neglects to fully defy certain (personal?) beliefs. Is it at the same time too much for 1989 yet radical perhaps? Comparing some other contemporary works with intimate relationships between women by other African writers (though an author might disagree with the perspectives of academics, readers, ect about their works or, or hold real life prejudices not clearly reflected in their work) the answer is it’s complicated— especially when works and concepts cross the globe. Today over three decades later, the matter is still a longstanding taboo causing stigmatisation. Though in 2020 Gabon did pass legislation to decriminalise homosexuality revising its laws, made formally illegal just a year previous. Unsurprisingly this revision decried by religious leaders. As well religious or spiritual themes appear in Rawiri’s novel. One instance is around another still relevant and big, taboo topic of the 1980s, HIV/AIDS. (FYI if you follow the link found in the previous paragraph the passage is quoted.)

While an example of the multiple way Rawiri also introduces parallels in the dichotomy of African vs Western, tradition vs modern, once more the writing is not evenhanded. Again, one must ponder the same question of time, culture, and literary canon. Too while the ending of the novel, I am not going to describe, can be interpreted as good for its protagonist, it is not necessarily well-written or without a dual edge.

However, what cannot be argued is Rawiri made her mark in history during a short writing career as her country’s first woman novelist in the 1980s, an influence inspiring more authors. Also, to her credit The Fury and Cries of Women, despite weaknesses, is writing that can still hold interest and is worth sitting with.

The Fury and Cries of Women by Angèle Rawiri is available in English, translated by Sara Hanaburgh, in print and digital from University of Virginia Press