#art institute of chicago

The Triumph of Silenus, Gerard van Opstal, ca. 1660

Port Scene in Calm Weather, Jean Baptiste Pillement, 1782

Les Andelys, Côte d’Aval, Paul Signac, 1886

A number of women who collected art are profiled in our current library exhibition, Deering, Palmer, Harding, Ryerson: Major Donors of Medieval and Renaissance Art. On view through April 24, the exhibition details the collecting habits of Bertha Honore Palmer (shown here in a portrait by Anders Zorn that is on view in the reading room); Marion and Barbara Deering (shown here in a portrait by Ramón Casas); and Carrie Ryerson, whose portrait is just visible in the upper right portion of this photograph of her Chicago home showing some of her art collection. Many of the artworks that these patrons gave to the Art Institute will be on view starting on March 20 in Saints and Heroes: Art of Medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Post link

Joel Sternfeld’s photograph The National Civil Rights Museum, Formerly the Lorraine Motel, 450 Mulberry Street, Memphis, Tennessee, August 1993 as it appears in On This Site: Landscape in Memoriam. The facing page reads:

Speaking at a rally on April 3, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said:

Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up the mountain. And I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want to let you know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. My eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

The next day, he was assassinated on this balcony outside room 306.

In honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the reading room will be closed on Monday, January 16.

Post link

This typographic image by Filippo Marinetti appears in a new digital catalogue for a recent experimental exhibition focused on modern art in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Shatter Rupture Break, by Sarah Kelly Oehler, Elizabeth Siegel, and Stephanie D’Alessandro, is available online free of charge.

This catalogue documents an exhibition of the same name devoted to the theme of fragmentation in life and art in the modern age. The first in the Art Institute’s new Modern Series, the exhibition offered fresh and innovative ways to consider the collection beyond standard practices. The same is true for this publication, which features a unique design catered to individual exploration. The digital catalogue includes an interactive section of works and didactics, an exhibition checklist, installation photographs, transcripts and videos of related events, and a compilation of visitor reactions.

Post link

In 2016, historian David Garrard Lowe, author of Lost Chicago, donated a collection of approximately 1,100 photographs and ephemeral items, ranging in date from the 1880s to the 1980s, to the Ryerson & Burnham Archives of the Art Institute of Chicago. The collection currently is in the process of being digitized, and a selection of materials is on display through June 15 in an exhibition in the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries’ Franke Reading Room.

The exhibition, “Memoir of a City”: Selections from the David Garrard Lowe Historic Chicago Photograph Collection, follows the table of contents in Lost Chicago, organizing the cases thematically around pre-Fire Chicago; culture and recreation in the city; residential architecture; transportation and infrastructure; government and commercial architecture; the 1893 and 1933 World’s Fairs; and significant Chicago people and events.

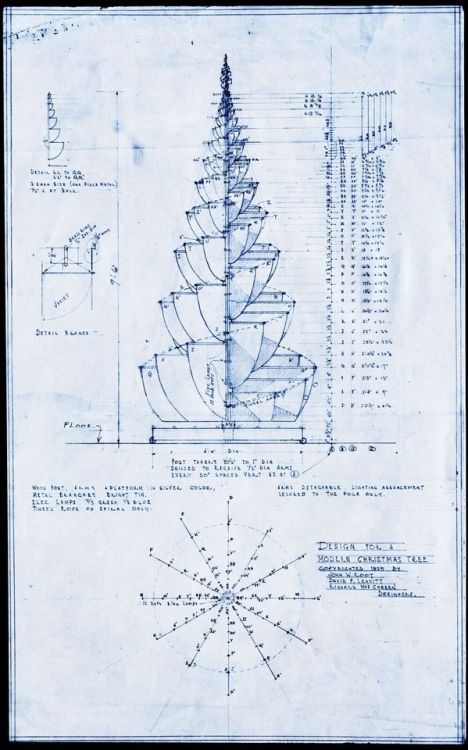

Viewers can explore a variety of primary source materials from the collection, including photographs that have not been published previously. Here you see an example of a photograph from the collection that was featured in Lost Chicago, Henry Ives Cobb’s Federal Building: US Post Office, Courthouse, and Customhouse, completed in 1905 and demolished in 1965. Below that is a design for a “Modern Christmas Tree,” a 1930 work by John Wellborn Root, David F. Leavitt, and Richard McPherren Cabeen. The exhibition also features the advertisement for this tree, which some scholars have suggested provided Irving Berlin with the inspiration for the song “White Christmas.” Other materials on display include menus, playing cards, postcards, and souvenir books.

If you’re planning to visit to view the exhibition, please join us for a conversation with David Garrard Lowe, “Lost Chicago"—The Past, Present, and Future of Historic Preservation,in the Morton Auditorium at 6:00 on Thursday, May 24. Lowe will be joined by author and former Art Institute of Chicago curator John Zukowsky; Founding Partner and Design Principal of the architecture, interiors, and urban planning firm UrbanWorks, Patricia Saldaña Natke FAIA; and School of the Art Institute professor and former director of research for the city’s Department of Planning and Development Historic Preservation Division, Terry Tatum, for a lively discussion on the history and future of historic preservation in Chicago’s rich architectural environment. He will also discuss Lost Chicago, and his gift to the Ryerson and Burnham Archives.

Post link

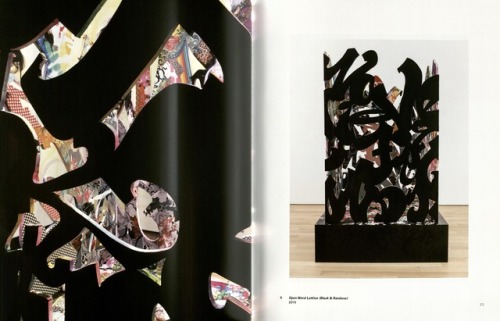

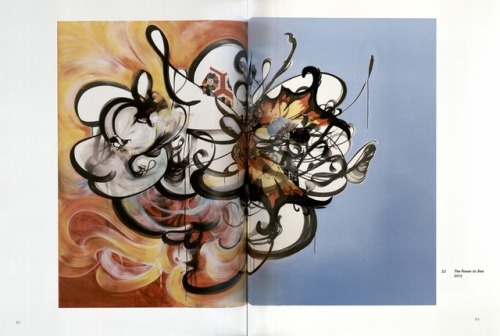

The work of Shinique Smith is a vivid explosion that reflects a wide array of the artist’s personal interests and experiences. Influenced by everything from graffiti and Japanese calligraphy to metaphysical spirituality and the rituals of burgeoning womanhood, Smith seeks to express the universality of the human experience in good times and bad, utilizing items that include found objects and used clothing. Materials about the artist and her work are available for viewing at the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries, including the 2016 publication Shinique Smith: Wonder and Rainbows.

Post link

I have become accustomed to going up the grand staircase at the Art Institute of Chicago and encountering El Greco. El Greco’s “Assumption of the Blessed Virgin” has been living at the Art Institute for a long time. Now, however, it has been joined by a number of other El Greco works, forming a thoughtful, engaging exhibition that brings together more El Grecos than I have seen in one place before (admittedly, I have not been in the Prado in Madrid, or Toledo, where El Greco lived and worked for so long).

Doménikos Theotokópoulos, who was known for most of his career and to history as “the Greek,” lived from 1541 to 1614. He was originally trained as an icon painter for the Orthodox church (and one of his icon paintings is included in the exhibit). Exposure to Venetian art caused him to change his style and adopt Western art practice. From Italy, he ended up in southern Spain, and gradually gained a career painting both religious subjects and court portraits. There were plenty of other artists at the time whose careers followed similar archs.

The problem is, the narratives of art history come up short when confronted with work as genuinely original as El Greco’s. Yes, I learned about how “Western art” traversed from Renaissance realism to mannerism and the Baroque in the late 16th century. The thing is, if you look at El Greco’s contemporaries (Bernini, Caravaggio, Vermeer, Reubens), they look very different from El Greco. In point of fact, it’s not the subject matter, but the painting style that’s so fascinating. El Greco’s acknowledgement of the painterly aspects of his work is more aligned with art of the late 19th century than it is with art of the 16th and 17th centuries. His elongated and attenuated figures are genuinely odd. Even if you rationalize that they were meant to be seen form below, it doesn’t explain why so many of the figures look stretched.

El Greco is also kind of like the 17th century Margaret Keane, the master of the Big Eyed figure. No other artist of the time was painting faces with these huge, liquid, tear-filled eyes. Yes, the works are uniquely appealing and emotional, but weirdly kitschy, in part because we have have come to associate big-eyed portraits with pop culture and canned emotional effects.

I also love the strange things that hands seem to do in El Greco’s work. Check out this detail from a portrait he did of a Spanish cleric. The middle finger of the guy’s left hand is keeping track of a page in a book. But the shape and shadow of the open book is extremely vaginal, and that middle finger appears to be gently probing or stroking the opening. The sly, sexy smile on the sitter’s face also suggest that there’s something more going on than keeping track of a text.

By the time you get to the works that El Greco created at the end of his life,things are getting pretty crazy. Yes, I could point to works by other Baroque artists that take considerable liberty with human anatomy, but this crowd of naked fabric-bunchers doesn’t make any sense to me at all. You will have to wait for Cezanne or Matisse, painting bathers in the post-Cubist world of the 20th century, before you find human forms this stylized. I am reminded of Leonardo da Vinci’s comment that Michelangelo made muscles look like a bag of rocks. These are sacks of potatoes with genitalia, giant naked Gumbies with their arms raised in supplication.

I also couldn’t help but think of the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard, who said that the Old Masters were nothing more than “assistant interior decorators to the Catholic rulers of Europe.” There are so many religious paintings here, sometimes in multiple iterations of the same subject, because, hey, the rulers of Spain were holding the line against the Protestant rebellions.They needed over-the-top emotionally intense Catholic art to hang on to their customers. El Greco provided that for them in spades, and did it in a way that radically predicts the fascination with materiality (paint for paint’s sake) that wouldn’t become common practice for another 250 years. Nice work if you can get it.