#bbc sherlock

[ The eleventh of 29 scenes from an in-progress johnlock fic. ]

It has been so very long since Sherlock has danced.

The delicate, lilting pianowork of Johannes Brahms’ Opus 39 pervades the usual quiet of 221B’s sitting room. A small iHome with Sherlock’s docked phone rests upon the cluttered table between the twin windows, the volume set loud enough so that it might drown out the annoying clamour of his intrusive thoughts. The music must be his focus, his centre; Sherlock cannot dwell on inconsequential things like touching or proximity because if he does, this will become much more unbearable than it ever need be.

Because it is already unbearable. It is. He knows it is and he’s doing it anyway because it is for John, and God knows he would do anything for John.

This means he will suffer John’s warm hand in his. He will suffer John’s strong arm across his shoulder blade. He will suffer the corrective touches he must give John along his side, his spine, his shoulder. He will suffer being close enough to see the furrow of concentration in John’s forehead and the dark, brilliant blue of John’s eyes.

This means he will suffer the horribly wonderful process of teaching John to waltz—not only because he is John’s best friend (a part of him still reels at this), but also because he has been appointed John’s best man. And the mantle of best man, he understands, is a momentous thing. It implies the chosen’s significance to the groom. It implies closeness and friendship. It implies trust. He is John’s best man, and he has every intention of fulfilling that role to the best of his abilities.

Which means Sherlock has done research. He has read that the best man’s duties can be extensive. He has read that those duties can include but are not limited to the following things: assisting the groom in choosing formalwear (check), organising the stag night (in progress), providing emotional support (mm, he’ll try), wrangling the groomsmen (none of those to speak of), entertaining guests (must he?), and giving a speech (also in progress). He has tacked sussing out guests with questionable or suspicious histories and being the groom’s impromptu dance teacher onto the list as well (in progress and also in progress) as he believes both to be in John’s best interest.

After all, Sherlock has laid his life on the line for John. Compared to a plotting criminal mastermind or a grotty Serbian cell, ensuring a perfect wedding is a rather small feat if one at all cares to look at the bigger picture. (Chance has it that Sherlock does, in fact, care to look at the bigger picture.)

And so in the spirit of fulfilling the role of best man, suffer Sherlock does.

John leads the waltz as they circle and sway about the sitting room, a gentle manoeuvre that has been refined to precision through repetition. Sherlock must narrow his attention to the crucial details of each component: the rise and fall of their steps, appropriate posture and form, the smoothness of underarm turns. He issues the occasional brusque command when John’s shoulders slack or when their tempo slows, but John always rights himself and continues his box step as if Sherlock had not said anything at all.

Truthfully, there isn’t a whole lot to correct other than the swing and the sway. This is the third lesson thus far, and to his surprise, John has proven himself to be a quick study. The beginning had been quite rough and full of smarting toes and the obvious lack of skill had been only the tiniest bit irritating, but John seems to have found his dancing legs at last. Sort of makes up for how rubbish he’d been at the start. And it’s—it’s nice. It’s good.

No. No, he must be honest with himself. It’s more than good. Far more than good. It’s brilliant. It’s amazing. It’s fantastic.

And if these were different circumstances—

Another song begins, flighty and playful, and Sherlock finds himself starting to slip. The tentative curl of satisfaction he’s managed to keep tamped down blooms into a sprawling, encompassing swath beneath his breastbone. He lets John guide him, move him, twirl him, shifting with fluid grace; he lets the music conduct his steps and the shapes of his inhales and the beat of his heart. It is excellent, wonderful, all-consuming, and he realises mid-turn that he doesn’t want it to stop.

It has been so very long since Sherlock has danced. Years, to be honest. Proper years. A decade or somewhere thereabouts. A younger Sherlock had attended a dull and stuffy affair he hadn’t wished to attend at all—Mummy’s behest. The ballroom dances had been its only saving grace. Going back yet another decade, an even younger Sherlock had balanced on his toes, testing the truest extent of control over his own body and feeling nothing short of alive. Ballet had brought him a certain type of high, one far removed from insidious things like glinting needles and seven percent solutions as there is nothing quite like the burn of straining limits or the rush of endorphins following uproarious applause. It always feels like sudden flight, like his heart has decided to launch up his oesophagus and into the stratosphere, and because his lungs never have anything better to do (breathing is boring), they always squeeze much too tightly in its absence, a physical plea: come back down,I’m lost without you.

(He thinks it must have alighted elsewhere that day. It must have crash-landed in another boy’s hands, miles and miles away. That boy must have tucked it into his pocket, unknowing, unaware, blissfully ignorant to the fluttering thump that had skyrocketed from the firmament and into his awaiting palms—a tiny quivering capsule composed not of cardiac muscle tissue, but of the metaphysical beat that drives one person closer to another: a tether, a string, a cord, a connection.)

(A heart.)

Of course, the years have added far more than ballet to his repertoire. He knows how to waltz, tango, foxtrot, quickstep, swing. He has forayed into ballroom samba and salsa, and he even knows a move or two when it comes to the club scene. Cases never call for dancing, so he never bothers to indulge, but that doesn’t stop the furtive hope that some day the opportunity will present itself, that he will have the chance to glide into old choreography like he glides into the familiar feel of a beloved dressing gown, its welcoming fabric soft with age.

And to have that opportunity present itself here, now—

God, it’s unfair.

It’s unfair because it is more intimate than a case could ever be. It’s unfair because it’s the wrong time, the wrong place. It’s unfair because of all the innumerable variables that could have contrived another outcome, of all the past events that could have culminated in some other meaningful moment, of all the conceivable situations that might require two people to dance, this is the one he never could have refused. It’s unfair because he is the best man—colleague, friend, forever confidant—and he has made it his personal mission to make John Watson as happy as possible.

But fairness doesn’t really matter, now, does it? Life has never been about what’s fair. This isn’t about what’s fair. This is about John. This is about John, his fiancée, his wedding, his happiness—because not only must John be kept alive, John must also be happy.

And isn’t it odd, Sherlock thinks, leaning into the sweep of another underarm turn, how the non-negotiable term has somehow negotiated into something more? Fascinating. Is it supposed to do that? He doesn’t know. All he knows is that John being happy is as integral as the limbic system: a necessary feature of the transport, an essential structure of the brain. John being happy is what makes the world right. It’s chemistry. It’s data. It’s fact.

The song continues, dulcet and bright, and against his better judgment, Sherlock succumbs. He basks in the closeness, the proximity, in John’s lifelines being flush with his. That serpentine swath of satisfaction curls and writhes beneath his skin, tenacious and insistent, pressing on the undersides of his ribs. He relishes the simple thereness of John’s presence slotted so closely with his, and his attention drifts from the mechanics, the components, the pieces, and instead narrows on everything John.

John and his tawny hair. John and his steel-blue eyes. John and his sapphire button-up. John and his well-fitting denims. John and his socked feet. John and his quiet exhales. John and his solid shoulder. John and his mellow cologne. John and his immeasurable strength. John and his blinding radiance.

John, John, John.

He takes a short breath, reeling (because he is John’s best friend; how on earth could he be anyone’s best friend?), and realises he is savouring this with far more fervour than a person’s best man ever should. It isn’t decent. It isn’t proper. It shouldn’t feel like oxygen is a scarcity or like his internal organs have been misplaced. It shouldn’t feel like a harpoon has been thrust through his very centre, prying him in two: I cannot do thisandplease let me in.

Sherlock keeps his gaze fixed on John’s shirt collar, and he—he wants.

He wants to dance with John. He wants the contentment of physical routine, of utter exertion. He wants the drip of sweat down his spine and a rhythm in his ear. He wants the pleasure of bending his own body to his will. There is such power and perfection in the exercise; to share it with a skilled partner is exhilarating, but to share it with someone like John encroaches the line of inebriation.

And as he follows John’s lead in the swaying tempo, John’s hand in his, feet shifting from ball to heel and back again, Sherlock knows, unequivocally, without algebraic formulae or scientific evidence, that dancing is not all he wants.

He wants to hold John. He wants to coast his palms up John’s sides, along his back, across his shoulders. He wants to frame John’s face between his hands, to let his fingerprints map John’s topography in every lineament, crease, and contour. He wants to take in the tiny flecks of hazel in the irises of John’s cobalt eyes and catalogue their placement. He wants to count the pores and the eyelashes and each little imperfection and commit them all to memory. He wants to lean close, feel John’s exhales, breathe them in.

The pull is there, tempting and persistent: he wants to kissJohn.

Nothing has terrified him more.

Sherlock must compartmentalise. Now. He must box it in and stow it away and do so with the utmost haste. He must shove it back into the deep recesses of his mind palace where it will never affect him again, where it won’t put a stutter in his pulse or a hitch in his lungs or a blaze in his belly. This is damage control: he must employ his masks of apathy, indifference, disinterest, because if not for a façade of unyielding marble, there would be nothing to stop John from seeing the fierce delight quaking in his chest.

And John must not see. Ever. The façade mustn’t crack.

The composition comes to an end and so does the waltz. Sherlock stills in the centre of the sitting room, the routine complete, and a long moment hangs in the ephemeral betwixt-the-songs-silence where he finds his body unresponsive. He knows standing here with one hand on John’s shoulder and the other in John’s (dominant) left can only contribute to an awkward set of expressions and excuses, and yet the muscles and tendons do nothing.

Because he wants. He wants. God, does he ever want.

Stop this, a composed Mycroft warns from the courtroom of his mind palace. Stop this immediately. Don’t torture yourself; you already know no good can come of it. Divorce the action from the sentiment and become the high-functioning sociopath you say you are.

Sherlock withdraws himself and takes a guarded step back, hands tightly clasped.

“All right?” he asks.

“Yeah. Yeah, I think so.” John sounds breathless. Looks breathless. A light sheen of sweat graces his brow, proof of the rigorous steps Sherlock has put him through during the past hour. “A bit nervous still, but—yeah, I think I’ve got it now.”

Sherlock feigns a smile. “You will do just fine, John. Admittedly it may take a while for my toes to fully recover from these sessions, but I’m sure Mary’s durable footwear will bear the brunt of the damage should you misstep.”

“Thanks,” John deadpans, casting Sherlock a rather tetchy glare. “Very reassuring, that.”

Sherlock dismisses the comment with a flippant wave of his hand. “Think nothing of it. It’s been a pleasure to guide you through an integral part of your reception. You’ve displayed such stellar coordination here this afternoon; I think Mary will be quite pleased.”

“I—you know, I honestly can’t tell if you’re being sarcastic,” says John.

“Sarcastic? Me?” Sherlock cannot resist the pull of a smirk. “Perish the thought.”

Adjusting his suit jacket, he steps over to the iHome and pauses the music. Even in the lesson’s aftermath, every note seems to hum under his skin. His body practically crows with the need to continue: a warm, solid weight lingering close, centripetal force tugging them round the sitting room’s centre, the pressure and heat of John’s hand in his. John can be prickly about his personal space when it comes to others, but never with Sherlock, and that calls to things that make his blood run hot.

Sherlock withdraws his phone from the dock, desperate for distraction. He swipes to the notifications, but there are no texts, no chat messages, no emails—proof of the ample time slot he’d set aside for this specific task. With a set jaw, he damns his past self and his ridiculous desire to accommodate. There should have been something else in the event of things going wrong, but no, he’d wanted to spend as much time with John as possible, and so here he is, suffering still.

Well, that has to stop.

“I’m going out,” he says, pocketing his phone.

John glances up. “Oh? Word from Lestrade?”

Sherlock makes a noncommittal noise as he crosses the sitting room for his coat, shoes, and gloves.

“I haven’t anything on,” offers John. “You know, if you could use the company. Afternoon’s all free. Mary’s looking at something else for the reception. Flower arrangements, I think. Or maybe serviettes. Don’t think she’d mind.”

Not now, he thinks in a fury, pulling on the familiar weight of the Belstaff. Can’t be now. Absolutely can’t be now. At any other time I’d literally sell government secrets to get you to come on a case, but that cannot be now.

Instead, he says, “Sorry, bit complicated, it’s—really, no time to explain. Time sensitive. Decaying tissue samples. You understand. Give my love to Mary, won’t you?” and promptly bolts out the door.

On the kerb, Sherlock flags a cab (because he must continue the pretence, John is watching) and gets in. He rattles off the address to Bart’s, the only place he can think to go where he might meander unimpeded for a while, and sits in the seat with his back straight and shoulders squared. Baker Street blurs in his periphery, 221B and John left behind.

A part of him wants to reach into his pocket and text, but there is nothing to text. There is nothing to say. There is only the reality that John Watson has his heart, and he can feel it as keenly as one might feel a missing limb. He doesn’t even know how that’s supposed to work—some days it’s as if something is sitting on his chest, and others it’s as if there’s a great void where the organ itself should be. He can still feel the thrum at the inside of his wrist during the latter and he fact that he still lives and breathes should be proof enough that it exists, but that does not stop him from wondering.

Slowly, Sherlock reaches for his phone. The weight is a stone in his palm. He presses it on to see the numbers 14:03 illuminate the lock screen. He stares at it for a moment, watching the time as it ticks to 14:04. And then, just below, the name ‘John Watson’ pops up in a text notification box.

Hey, I know you’re busy but I just wanted to say thanks for …

The grit in the instrument, he thinks. The crack in the lens.

Sherlock does have a heart. And it has been burnt, just as Moriarty promised. But perhaps it landed in John’s hands that day.

That might explain why John has had it ever since.

FOLLOW ME https://www.instagram.com/olga_tereshenko/?hl=en

Sherlock

Watson

Moriarty

My series of portraits based on BBC’s Sherlock.

Post link

FOLLOW ME https://www.instagram.com/olga_tereshenko/?hl=en

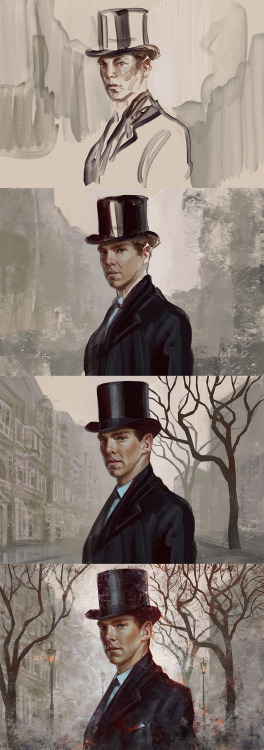

Work in progress

Sherlock

Benedict Cumberbatch

The Abominable Bride

Post link

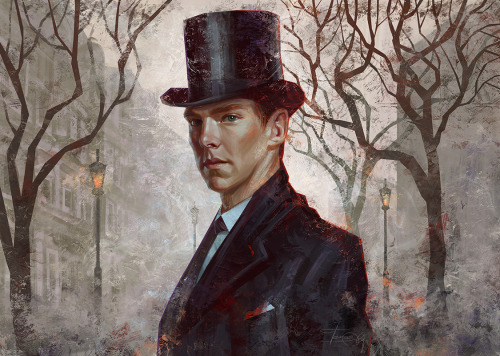

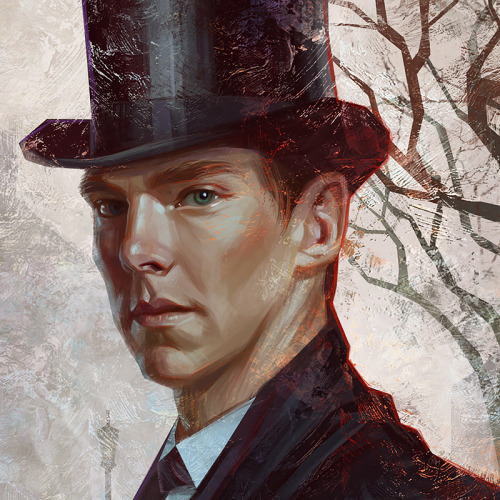

Sherlock

Benedict Cumberbatch

The Abominable Bride

https://www.instagram.com/olga_tereshenko/

Post link

Jeremy Brett was a feminist. He would never have tolerated the depiction of suffragettes as conspiratorial terrorists and murderers using the tactics of the KKK, and neither would Doyle. Not even with Mr. Creosote Mycroft saying that they had to win. That contemptuous insult was meant purely for the ardent end of the fan base. Of course it’s a clue intended to denote that there is an army of Moriartys, as well as all the other clue baits Moftiss has riddled the show with, but I am now finished with this game. BBCS is nice plot crack and slick production, but the moral meat and potatoes of Doyle is lost to all of them.

The best thing Moftiss ever did was fail to provide a seasonal shooting schedule for BBCS so that the principals could go on to fame and fortune. It made me put down the fandom banner and take up Canon and Granada, and I haven’t looked back since.

Mrs Hudson: “I’m your landlady, not a plot device.” And then suffragettes become an army of plot devices. Ironic much? Women can be bad guys, occasionally, with real motive. We can even be individual assassins if the need arises. But to put us in an organized tactical bed with the Ku Klux Klan is an insult to the gender which holds all of humanity to a moral bar of genuine goodness- that *man*kind persistently fails to raise itself. A vast section of Doyle’s Canon concerned itself with protecting abused and wronged women, and Dr. Joseph Bell’s invention of CSI was extremely motivated in solving such crimes. The ripper was the prime example.

I find it ironic that it was Victorian men and Jeremy Brett who could so easily comprehend this. To depict women as stooping to answer their treatment in the same fashion as organized terrorists is infuriating at minimum. And to make us use orange pips and pointy hats…done, Moftiss. So done.

that episode was 99% fanfiction straight from Mark Gatiss’ diary.