#beaked whales

When people hear ocean pollution, they immediately think of the visible ones like plastic pollution, oil spills or sewage run-offs. But sound pollution, this invisible threat, is just as devastating to numerous marine animals, especially whales. Remember ‘The Silent World’ from Jacques Cousteau? Well, our oceans aren’t so silent anymore.

Historically, noise levels in the oceans were low enough that whales were able to use their sonar to communicate with each other or to hunt for food. Increased ship traffic, acoustical seismic testing for oil exploration, the use of military sonar, and even small boats in high concentrations have all contributed to the growing sound pollution in the oceans.

Sound travels farther and about five times faster in water than in air. All these high intensity sounds also travel at a higher energy level so they are louder than they would be above the surface. This increased cacophony has made the use of sonar, echolocation and underwater communication between whales extremely difficult. Imagine basically walking around on the airport runway with airplanes landing and taking off every minute or so trying to have a conversation with a friend….except that it’s even louder, and it never stops.

Susan Parks, a biology professor at Syracuse University, compared right whale calls recorded off Martha’s Vineyard in 1956 and off Argentina in the 1977, with those in the North Atlantic in 2000. Parks and her team were astonished with the results. They discovered that North Atlantic right whales actually shifted their calls up an entire octave over the past half century in an attempt to be heard over the unending and increasing low-frequency sounds of commercial shipping. Furthermore, right whale songs used to carry off 20 to 100 miles, but now those calls travel only five miles or so.

Another interesting tidbit of Park’s research came after 9/11. With the commotions and confusion following the attacks, ship traffic drastically dropped for a while. Her team continued recording whale calls during that time, and they could not believe what they heard. Actually, they didn’t hear much. The acoustic fog that had settled on the oceans for decades had suddenly lifted. Furthermore, they analyzed stress hormones found in collected whale poop, and they found that they had considerably dropped. It was obvious that during that brief period of time, whales had finally relaxed.

If whales can’t hear each other as well, they need to spend more time and energy moving around and travelling to ‘quieter’ places in the oceans in order to feed or mate. This seems small, but a prolonged exposure to excessive noise can lead to permanent behavioral changes and thus a long-term impact on population numbers and mortality rates. Additionally, loud sounds have direct impacts on whale hearing, stress levels as we have seen above, and in some extreme cases may cause internal bleeding and death.

(Source: National Geographic. Click for full size.)

Astudy published in 2014 in the journal PLOS One found that manmade noise pollution can literally make whales go insane. Moreover, scientists have also found that beaked whales are extremely sensitive to sound pollution. They tend to dive too deep when they hear loud noises, then resurface too quickly and can die from the bends. Other studies have blamed military sonar and mapping sonar by oil companies for mass strandings of marine mammals.

What can we do about it? Governments are slowly starting to become conscious of the problem, and some are trying to slow ships down or to re-direct traffic to areas not ecologically significant to marine mammals, but of course this comes with a lot of opposition from the companies, as even a detour of five miles off course can increase costs and time. Many NGOs like Oceana and Greenpeace are also campaigning against the use of seismic blasts for exploration drilling. Technologies are also being developed to drastically reduce the noise from ships and geological surveying. We still need to continue raising awareness on the problem so further political action can occur and some international standards can be set.

You can check out this interesting interview with Christopher Clark, a prominent bioacoustics researcher. Clark goes into more details about seismic blasts and the precise impacts noise pollution may have on whale populations. It’s a great read.

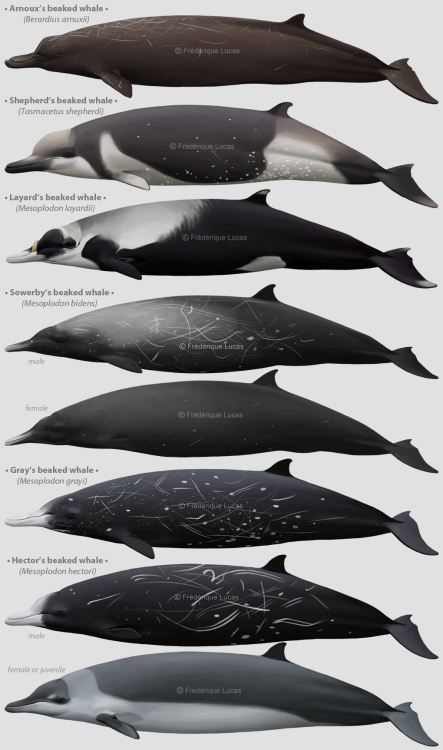

A bunch of beaked whales

I did mention I got to paint a lot of beaked whales, right? ;) After the bottlenose whales here are, well, the others. I thought it was nice to put them all together, really makes you appreciate the wonderful diversity within this big family (and it saves you from ‘a beaked whale a day’ for the next 1.5 weeks). There’s too many to all discuss individually but I have some favourites:

Shepherd’s beaked whale was a joy to paint as they are one of my favourites. Their markings are so beautiful, and they are also unique in being the only beaked whale to have a full set of teeth. For very long their colour pattern was unknown (and oft presumed to have this streaky pattern) until in 2006(!) their real colouration was formally described. They are a beautiful, elegant and unique looking species.

Sowerby’s beaked whale provided a similar ‘aha’ erlebnis for me. Often illustrated as a medium gray throughout (which is certainly fitting for the females) some interesting photographs of adult males showed a rather distinctive light blaze between their blowhole and dorsal fin. In some males it was very subtle, but others had almost as much contrast as a Layard’s beaked whale - I chose to illustrate something in the middle. Very interesting and something I hope will be the subject of further study. Males and females also have funny white lips.

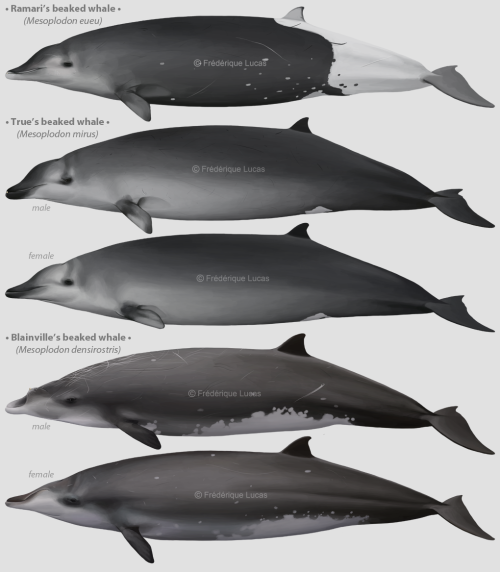

Ramari’s beaked whale can’t be overlooked as it is the youngest member of the family: only described three months ago, in October 2021. Previously known as the southern form of the True’s beaked whale, analysis proved they were a species all of their own. Very happy to have painted this one too, as the mysterious southern True’s with their shining white peduncles always intrigued me.

And lastly, I can’t not mention Blainville’s beaked whale becausetake a closer look at that snout. Any whale whose mouth somehow ends up above their eyes is worthy of an extra look I think. And the Layard’s beaked whale because they have always been my number 1 favourite beaker.

Post link