#ocean conservation

When people hear ocean pollution, they immediately think of the visible ones like plastic pollution, oil spills or sewage run-offs. But sound pollution, this invisible threat, is just as devastating to numerous marine animals, especially whales. Remember ‘The Silent World’ from Jacques Cousteau? Well, our oceans aren’t so silent anymore.

Historically, noise levels in the oceans were low enough that whales were able to use their sonar to communicate with each other or to hunt for food. Increased ship traffic, acoustical seismic testing for oil exploration, the use of military sonar, and even small boats in high concentrations have all contributed to the growing sound pollution in the oceans.

Sound travels farther and about five times faster in water than in air. All these high intensity sounds also travel at a higher energy level so they are louder than they would be above the surface. This increased cacophony has made the use of sonar, echolocation and underwater communication between whales extremely difficult. Imagine basically walking around on the airport runway with airplanes landing and taking off every minute or so trying to have a conversation with a friend….except that it’s even louder, and it never stops.

Susan Parks, a biology professor at Syracuse University, compared right whale calls recorded off Martha’s Vineyard in 1956 and off Argentina in the 1977, with those in the North Atlantic in 2000. Parks and her team were astonished with the results. They discovered that North Atlantic right whales actually shifted their calls up an entire octave over the past half century in an attempt to be heard over the unending and increasing low-frequency sounds of commercial shipping. Furthermore, right whale songs used to carry off 20 to 100 miles, but now those calls travel only five miles or so.

Another interesting tidbit of Park’s research came after 9/11. With the commotions and confusion following the attacks, ship traffic drastically dropped for a while. Her team continued recording whale calls during that time, and they could not believe what they heard. Actually, they didn’t hear much. The acoustic fog that had settled on the oceans for decades had suddenly lifted. Furthermore, they analyzed stress hormones found in collected whale poop, and they found that they had considerably dropped. It was obvious that during that brief period of time, whales had finally relaxed.

If whales can’t hear each other as well, they need to spend more time and energy moving around and travelling to ‘quieter’ places in the oceans in order to feed or mate. This seems small, but a prolonged exposure to excessive noise can lead to permanent behavioral changes and thus a long-term impact on population numbers and mortality rates. Additionally, loud sounds have direct impacts on whale hearing, stress levels as we have seen above, and in some extreme cases may cause internal bleeding and death.

(Source: National Geographic. Click for full size.)

Astudy published in 2014 in the journal PLOS One found that manmade noise pollution can literally make whales go insane. Moreover, scientists have also found that beaked whales are extremely sensitive to sound pollution. They tend to dive too deep when they hear loud noises, then resurface too quickly and can die from the bends. Other studies have blamed military sonar and mapping sonar by oil companies for mass strandings of marine mammals.

What can we do about it? Governments are slowly starting to become conscious of the problem, and some are trying to slow ships down or to re-direct traffic to areas not ecologically significant to marine mammals, but of course this comes with a lot of opposition from the companies, as even a detour of five miles off course can increase costs and time. Many NGOs like Oceana and Greenpeace are also campaigning against the use of seismic blasts for exploration drilling. Technologies are also being developed to drastically reduce the noise from ships and geological surveying. We still need to continue raising awareness on the problem so further political action can occur and some international standards can be set.

You can check out this interesting interview with Christopher Clark, a prominent bioacoustics researcher. Clark goes into more details about seismic blasts and the precise impacts noise pollution may have on whale populations. It’s a great read.

In a news release earlier this month, the IUCN revealed that increasing anthropogenic pressures (such as fishing and boat strikes) have caused the rapid decline of whale shark populations and that they should now be considered as endangered.

TheInternational Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is the world’s main authority on the conservation status of species. The IUCN Red List evaluates the extinction risk of thousands of species based on a precise set of criteria, and the resulting evaluation aims to convey the urgency of conservation of a species to the public and policy makers.

Previously, whale sharks were ‘vulnerable’ to extinction, but their status has now been updated to ‘endangered.’ Their numbers have more than halved over the last 75 years as these sharks continue to be fished and killed by ship propellers.

Dr. Simon Pierce and Dr. Brad Norman, two prominent whale shark scientists have spent decades studying the animals and have co-authored the assessment that led to IUCN’s update.

“In our recent assessment, it was established that numbers have decreased more than 50 per cent in three generations – which we estimate to be about 75 years,” Norman explained. “The numbers on a global scale are really concerning.”

The main stressor to these gentle giants is the intense fishing pressure in several countries, including China and Oman, especially for shark-fin soup. Some other nations such as India, the Philippines and Taiwan have started implementing conservation plans and have ended large-scale fishing of whale sharks. While these efforts are admirable, it is now really important to push for more regional protection in these countries and to push other countries to try to save this species.

Whale sharks have been hard to study and to keep track off as they are quite cryptic and disappear into the open ocean fairly quickly. However with the use of modern technology and tagging devices, it has become a lot easier to follow them, collect information on them, but also to realize what kind of threats they are facing.

The species is just one step away from being critically endangered, an IUCN listing that is very hard to come back from.

“We cannot sit back and fail to implement direct actions to minimize threats facing whale sharks at the global scale,”saidNorman,“It is clear that this species is in trouble.”

Tonight’s line-up:

- Tiger Beach (8/7c)

Dr. Neil Hammerschlag is the world’s leading tiger shark expert. Now, he’s on a quest to answer what he calls the trifecta of tiger shark science: where do these giant sharks mate, where do the pregnant females gestate, and where do they give birth? He hopes to find answers by tagging and tracking 40 individuals across a shallow area off the Bahamas called Tiger Beach. Second only to great whites, the tiger shark’s killing power and voracious appetite is legendary - and Neil has to deal with some aggressive sharks while on expedition.

- The Return of Monster Mako (9/8c)

Professional shark tagger Keith Poe, and marine biologists Greg Stunz, Matt Ajemain and their team use state-of-the-art technology to try to document a live-predation of a thousand-pound mako shark – what fishermen call a “grander.” Granders are enormous makos that make a kind of transformation when they reach 10 feet and 1000 pounds - they become more secretive and begin to hunt bigger prey, like seals. And they’re hard to find on the East Coast - until Joe Romeiro and team jump in the water after dark and come face to face with them.

- Isle of Jaws (10/9c)

In 2016, award-winning shark cinematographer Andy Casagrande discovered that great white sharks had strangely and completely disappeared from the Neptune Islands off South Australia. Where did the sharks go? Searching west along the known great white migration route, he stumbles upon an incredible discovery - a concentration of all male great white sharks off an uncharted island. Andy calls in marine biologist Dr. Jonathan Werry, and together they get up close and personal with a dozen large great whites in the hopes of solving two of the most closely guarded of all the great white’s secrets… where they mate and where they have their young. Within this program, viewers will be able to immerse themselves into the adventure with virtual reality by using the DiscoveryVR app.

Check out the full TV Schedule here.

Finding Dory, the sequel to Finding Nemo, is coming out today, June 17th 2016. A few years ago, Finding Nemo was such a massive success that it drove demand for pet clownfish through the roof, and resulted in hurting the wild population, instead of fostering an appreciation for marine animals in their natural habitats. Over 90% of the clownfish sold came from the big, blue sea! Let’s avoid doing the exact same thing with Dory, shall we?

The case of Dory, or the case of blue tangs, is a bit different from clownfish. A “Finding Nemo effect” and a similar pet-trade boom could have catastrophic results for this species.

First of all, blue tangs aren’t bred in captivity. Blue tangs are pelagic spawners, meaning that they need sufficient space to breed and mate in mid-water columns. Once the eggs are hatched in captivity, it is extremely difficult to keep them alive. This means that every blue tang you will see in tanks or at the pet store has been taken from the wild.

Second of all, chances are they were taken illegally.Regulations and their enforcement vary from country to country, but live saltwater fish like Dory are too often illegally collected using sodium cyanide as a liquid stun gun. For clownfish, scientists have witnessed local extinctions in areas they were collected in, and to the destruction of reefs and other species with this method.

Moreover, very little is actually known about the species. Subsequently, researchers don’t know if the blue tang population would be able to withstand increased demand after the movie release.

Behavioral ecologist Culum Brown works on fish cognition and welfare, and he reveals what is known about the species in an interview with NPR:

“You’ll be shocked to discover that we actually know very little about cognition in blue tangs. Correction … make that nothing. But that is true for the vast majority of the 32+ thousand species of fish out there.

"We know that their skin reflects light at 490nm (deep blue) and they tend to get lighter at night (this is under hormone control). They have very sharp spines on either side of their tail which erect when [the fish are] frightened. They have a huge distribution (Indo-Pacific) but are under threat from illegal collection. They graze algae on coral reefs, which is a very important job because it prevents the corals from being over-grown.”

So what can you do to save Nemo and Dory?

If you must have a clownfish in your tank, make sure it was bred sustainably in captivity and not taken from the wild. As for having a Dory, you get it, it’s a big no-no. Keep Dory on the reef.

The aquarium industry harvests more than 1 million clownfish from their natural habitats every year so they can be sold as pets. This overharvesting, along with other stressors like global warming, is likely leading to the depletion of clownfish populations in places like the Philippines and the Great Barrier Reef.

Captive breeding has proved to be a sustainable alternative that can meet the demands for ornamental fish like Nemo, without hurting the reef’s populations. Tank Watchis also an app that helps you identify the captive-bred (good) from the wild-caught (bad) fish.

While you go out and see this movie over the weekend, remember to educate yourself on the many species represented (including a whale shark and a beluga whale!). Many of them are under some sort of threat in the wild. All of these species are better off out in the sea, so if you fall in love with one of them and instead of taking Dory out of the ocean, I hope you moviegoers will support research, education and conservation!

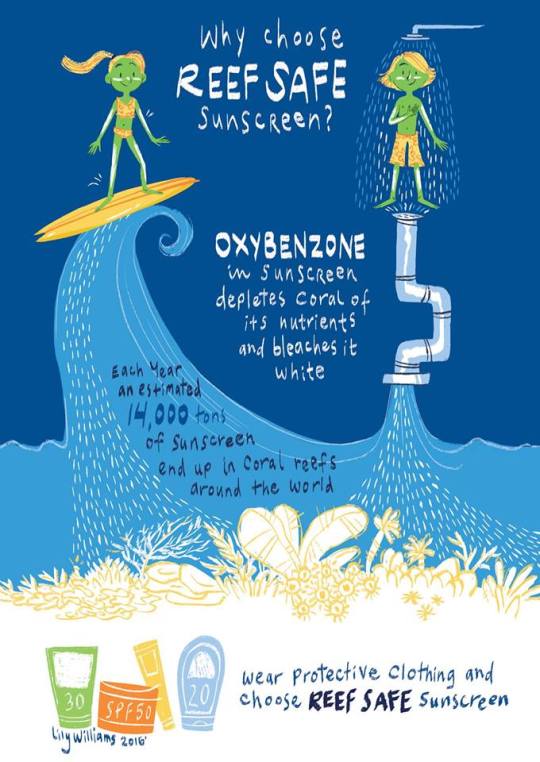

We all know that sunscreen is a must when going out in the sun if we don’t want to end up looking like a red lobster. But have you ever noticed that oily slick that appears around you when you go for a dip into the ocean? Have you ever wondered where all that sunscreen goes? As summer has arrived in the northern hemisphere, I figured now would be a good time to address this.

(Photo from The Nature Conservancy’s Hawaii Marine Program)

It turns out that your sunscreen, specifically the chemical oxybenzone, may be contributing to the decaying health of the coral reefs according to a studyfirst published in October 2015 in the journal Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Oxybenzone causes endocrine disruption, DNA damage and death. It also exacerbates coral bleaching.

Now, you may think that just you and your sunscreen cannot possibly have an impact since the ocean is so big and all. However, somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000 tons of sunscreen enters coral reef areas around the world each year, according to the U.S. National Park Service.

That’s… a lot of sunscreen (and people), especially considering how little it takes to cause toxic effects. According to the study mentioned above, toxicity occurs at a concentration of 62 parts per trillion.

Measurements of oxybenzone in seawater within coral reefs and popular tourism areas in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands found concentrations ranging from 1.4 parts per million to 800 parts per trillion.That’s 12 times the concentrations needed to harm coral.

“The use of oxybenzone-containing products needs to be seriously deliberated in islands and areas where coral reef conservation is a critical issue,” says Craig Downs, one of the authors on the study. “We have lost at least 80 percent of the coral reefs in the Caribbean. Any small effort to reduce oxybenzone pollution could mean that a coral reef survives a long, hot summer, or that a degraded area recovers.”

Obviously, I am not telling you to stop using sunscreen! However, we must consider carefully what sunscreen we buy before swimming in the ocean. The National Park Services highly recommend the use of mineral sunscreens with titanium oxide or zinc oxide, as they have not been found to harm reefs.

Sunscreen by itself is not destroying coral reefs around the world. However, it is one more threat down the list working against these animals: warming sea temperatures, pollution, nutrients run-off, overfishing… If we start adding together all these little things, they all reduce the resilience of coral reefs to withstand bigger things like bleaching and disease.

We can do our part to help the corals by simply choosing oxybenzone-free products. I won’t get into that, but I have also read that oxybenzone is not very good for us humans either anyways.

Here are some of the brands I know of in the USA that do not contain oxybenzone: Stream2Sea,Badger Sunscreen,Cerave andSun Worshipper sunscreen. In France, I know of the brand Evoa. Either way, aim to purchase oxybenzone-free, organic and/or mineral sunscreens, rather than chemical sunscreens.

UK based