#dyson sphere

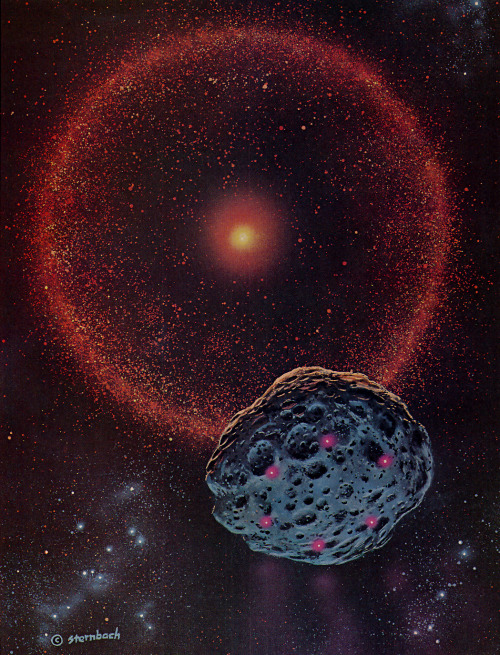

Concept art by Rick Sternbach, depicting the construction of a Dyson sphere via ion thrusters nudging astroidal rock into place.

Post link

I was looking through the shelves thinking which book to write about next and I came across Stapledon’s Star Maker. I’d read it recently and it’s a remarkable book (rather, it’s an ongoing read*). I thought it wouldn’t be suitable as it was re-published as part of Gollancz’s SF Masterworks series, I thought it was still culturally significant. Yet, looking through a number of ‘greatest science fiction’ lists (I know I shouldn’t do that). It was notably absent, even from Pringle’s list. Looking through the NPR list World War Z was in the top 50, but no Stapledon. Anyway, I’m not here to rant on relative merit, I’m here to talk a little about a classic work of literature that seems to be slipping.

So, a little about the author. Stapledon’s known as much for his academic work as for his fiction writing. His earliest academic publications were in the realm of philosophy and psychology, though these were preceded by a couple of volumes of poetry from 1914 and 1923. his philosophical ideas around society and community passed through into his fiction, starting with Last and First Men of 1930. Stapledon’s works was read by many of the next generation of SF writers.

Star Maker itself was highly acclaimed by a number of contemporary writers including Woolf, Wells and the outstanding Borges. Arthur C. Clarke is noted for having been highly influenced by the novel. Within the first few pages, Stapledon does something I absolutely love in science fiction; he dismisses entirely the science. We’re taken on an odyssey to the edges of our galaxy with no mention of the method. That’s not to say the science is lacking, Freeman Dyson’s Dyson sphere was based in part on Stapledon’s idea. His discussion of a collective mind is also quite a forward-thinking idea for the time.

It is a tricky book though, I had to rest after the first few pages because the overall feel of the writing is quite colourless - it reads more technical than dramatic. However, given the breadth and depth of ideas therein it is certainly an important milestone in the history of speculative fiction, particularly as it exists in that hinterland between the birth of science fiction and it’s full flowering.

The book was published on the 24th June in 1937 (initially intended to be the 10th) by Methuen. The first issue is identified by having blue boards with red lettering. Here’s a link to our copy of the first British edition in the Bip Pares jacket: £2750

* The ongoing read has been something of a habit of mine for many years, but only recently have I structured it into my reading habits. I figured that a novel is on average 250 pages long. I figured a short story is around 20 pages. One novel is roughly equal to around 12 short stories. I find it difficult to sit and read a full book of short stories. So here’s how I structure it; I read a novel, then 12 short stories (or novellas etc). But rather than read 12 stories by one author I read 12 stories by 12 authors. So the last iteration in the cycle was: [Novel] Ubik, [Shorts] Grimm’s Fairy Tales, J.G. Ballard, H.P. Lovecraft, Sophocles, Neil Gaiman, Arabian Nights, John Milton, Virgil, Malory, Asimov, E.T.A. Hoffman, Ray Bradbury. Anyway, just thought I’d share because it works for me!