#book collecting

Emily loved books.

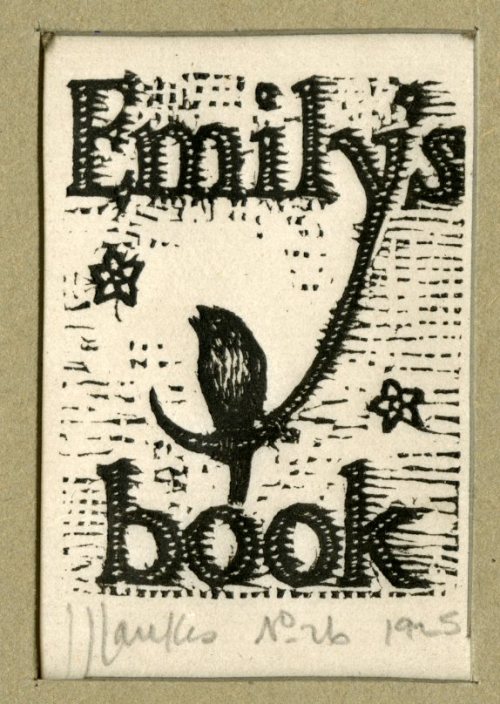

J.J. Lankes bookplate, 1925 from the Adèle Goodman Clark papers, 1849-1978, Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library. A Lankes’ sketch for this bookplate may be found online.

Post link

‘Frances Wolfreston her bouk’

A shelf-check undertaken in 2019 turned up a book held by the Alexander Turnbull Library that was once owned by the 17th-century collector Frances Wolfreston (1607-1677), a gentrywoman who formed a substantial library focused primarily on English literature and drama. (Better late than never to announce the find!)

The book is The dance machabre or Death’s duell:a metrical treatise on death composed by the English Franciscan friar Walter Colman (1600-1645). It is also an extremely scarce work, with just nine copies recorded in the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC). Wolfreston’s ownership inscription appears on the first page of verse.

In her will, Wolfreston bequeathed her library to her son Stanford (b. 1652). Her collection remained with the family until the mid-19th century when much of it was sold by Sotheby’s in 1856 and dispersed.*

Wolfreston’s copy of Colman’s La dance machabre was purchased in the Sotheby’s sale by the writer and book collector George Daniel (1789-1864), whose collection was sold over a ten-day period in July 1864 just a few months after his death. La dance machabre was lot 377 and was acquired by Joseph Lilly on behalf of the notable bibliophile Henry Huth (1815-1878). His 'Ex Musæo Huthii’ book label is present on the front pastedown.

Huth’s vast library was auctioned in a series of Sotheby’s sales that took place between 1911 and 1922. La dance machabre was sold in 1912 (lot 1702), and was likely knocked down to Bernard Quaritch on behalf of Alexander Turnbull.

Although his bookplate is not present, Turnbull purchased numerous books in the Huth sales - most notably Huth’s complete set of Theodor de Bry’s voyages in both the German and Latin editions - and like Wolfreston he had a particular interest in English literature. A work as scarce as Colman’s La dance machabre with such a collecting lineage would not have escaped his eye.

*For the wonderful project being led by Sarah Lindenbaum that seeks to list the surviving books from Wolfreston’s library along with their present locations (including the book described here) see:

https://franceswolfrestonhorbouks.com/

The website records over 230 books to date. Here is to the discovery of many more!

–

Walter Colman, La dance machabre or Death’s duell. London: printed by William Stansby, [1632?], Alexander Turnbull Library, REng COLM Dance 1632

A lovely copy of William Morris’ Kelmscott Chaucer came to market recently (last year, but that is recent in book collecting). It sold for in excess of £100,000, quite an increase on the £20 it originally sold for in 1896. If you’d put £20 in the bank in 1896 on an exceptional deal that promised you 5% per year but you were locked in for four generations, you’d have a balance of about £8,000. In fact, to get more than £100,000 back on your original £20 over the course of 12 decades, you’d need a fixed interest rate of around 7.2% (assuming monthly compound interval; you’re fixing for 120 years, you set the terms) to realise more than £100,000. It’s astounding how big a difference an interest rate makes over a long period (20% puts you at nearly half a trillion, I’m sure there’s a book plot where that happens somewhere).

You see, that example just shows how buying rare books is a much better nest egg than putting the money in the bank, creating a pension, investing in stocks and shares, property. Actually, it doesn’t, the example shows you nothing. Firstly, banks don’t do that, though sadly it’s the interest rate that seems more elusive than the 1440 month term. Secondly, you didn’t buy a Kelmscott Chaucer in 1896 and will never have the opportunity to get one at that retail price. Thirdly, you won’t live until you’re 120, modern science might think you will, but modern science neglects the social armageddon (wherein nobody looks up from their phones for months, all physcial interaction ceases, until the last human dies on a toilet waiting for a like on Instagram, thinking it’s because nobody likes their duck pout rather than the fact that nobody else is left alive. That or Zombies).

Fig 1. A facsimile, we haven’t had the 1896 edition, but that’s a different story.

So what is a good example?

Well, Sotheby’s sold a copy for just shy of £20,000 in 2000. It wasn’t pristine and lacked a couple of ties. But still, £20,000 nowadays for it would be cheap. It wouldn’t be a £100,000 copy, but certainly more than £20,000. Let’s £40,000 as there’s a similar copy on the market at that price. Doubled in 15 years, that’s not bad. An average interest rate of 3% over the last 15 years, would have given you £31,000. So that’s great, £9,000 extra, and you have had a Kelmscott Chaucer to look at for 15 years, albeit one lacking ties and a bit skewed and probably in a box - damn you Sotheby’s selling such junk.

So that’s a great example?

Well, it’s certainly more realistic. But let’s face it, the Kelmscott Chaucer is probably the most desirable book ever produced (if you don’t count that gaudy, bejewelled Rubaiyat that’s currently being devoured by lampreys beneath a smug iceberg at the bottom of the Atlantic). If a book was ever going to maintain demand over the decades it would be the Kelmscott Chaucer. So it’s an unfair book to chose.

On top of that, £40,000 is the market price. It’s also the price at which that particular book hasn’t yet sold for. That’s not to say the price is wrong, it just hasn’t found its buyer yet. It will, I’m sure. Books, even desirable ones, can take a good while to sell (interestingly, the £100,000+ fine copy I referred to above sold almost immediately, rarity and condition are the power-combo). Books just aren’t that liquid. I read a piece the other day about the legendary bookdealer A.S.W. Rosenbach, in one letter to Frank Hogan he’d written: “I am as hard up as the devil and I would appreciate it more than I can say if you send me a check for $4,180.″ That was something in the realm of £75,000 back then but still a fraction of the amount Rosenbach was used to dealing with, also, it was 1933 and a bit depressiony. Still, the point is, Rosenbach, needed money and yet he had shelves full of ridiculously nice items. Books aren’t liquid.

So, you’re resigned to the fact that it’s going to take a while to sell, but you want the money so you email your favourite dealer who offers you £20,000 for it. You ring your second favourite dealer who offers you £25,000. You ring that dealer who you thought was a little bit hairy and creepy, he offers you a staggering £30,000 for it, because he has a customer for it and…you never get the other reason because the phone call tails off into mumbling and, you think, some version of vocal snoring. You realise you might as well have had the money in the bank.

You take the book to Sotheby’s, after laughing at the condition and joking that they can’t believe they sold such junk (ah, the dot-com bubble) they tell you it should have a low estimate of £35,000. You smile and set the reserve. They tell you their fees are 25%. They tell you their buying fees are 25%. If it sold for £40,000 you’d still only be at £30,000 (assuming no other fees).

You think about putting it on eBay or Amazon but it has no barcode, and your pictures aren’t at the right resolution. Plus, nobody can get in touch with you because you can’t use their inane messaging system. On top of that you get crazygeoff74offering you £250 and 37 metres of copper pipe every few days, increasing his offer gradually to £273.50 and including a 1994 Ford Fiesta without an MOT or carburettor. you decide eBay isn’t the way to go.

Selling books is hard, not always hard work (often hard work), just hard to do. There are five Kelmscott Chaucers on the market, the finest book ever produced, there should be none. It’s a hard game.

So what is a good example?

Well, that’s kind of the point. There aren’t any useful ones. There are plenty of books that have increased well beyond inflation and bank rates, but there are plenty of stocks and shares that have done that too. If retrospective review gave a series of flawless, reusable guidelines then they’d be guarded jealously or the market would collapse. Let’s try Birdsong for example, I recently sold a copy for £150. Retail was probably around £15 a decade ago. Great example, it’s a great book, well written, quick to reprint so scarce, but common enough to keep the market buoyant. You should’ve bought them years ago, whole carrier bags full (and you’d have got the bags for free back then). But I’m fairly sure I’ve sold copies in the past for £300. So is the price dropping? Maybe, maybe it’s done, maybe it’s a dead book, maybe it’s demand has dropped, there was a TV show, maybe that changed things, maybe it Faulks’s curly hair that nobody likes, maybe the hype’s died down, maybe the good collections all have copies now, maybe it’s just taking a few years to gather speed again, maybe people have forgotten about it because it hasn’t quite got over that awful wave of desire for modern books over those tried and tested for generations, maybe, maybe, maybe. If you like the gamble, be my guest.

Fig 2. Birdsong, we’re currently out of stock.

It wouldn’t be unreasonable to ask why I’m telling you all this, someone whose living is to be made from selling books and should be encouraging people to buy them as investments, because selling books is all we do right?

Well, other than the fact that nobody reads this blog (I could be telling you to stop buying books and collect PDFs on floppy disks, it wouldn’t matter). the truth is that mostcollections we buy we pay more for than the collector did. The reason I’m telling you this is because I don’t like to hear the disappointed tone in emails when I suggest to people that their collections aren’t worth what they think (I assume it’s a disappointed tone, you never can tell with emails, they may be elated, if only there were some kind of emotional icon one could use).

So, why do some collectors get more than they paid, and why do we disappoint some collectors? Here’s the rub. Most of the collections we buy are from collectors who’ve bought for the love of books. I’m going to capitalise that THE LOVE OF BOOKS. These are people who have spent decades, usually, finding the finest books for their collection, hunting rare items for years, taking them to conventions dressed as Spock to get them signed. Their love for the books has enabled them to get the really desirable things, things they’ve had to wait years for. Things other people want, and if other people want them then so do we (sometimes).

The corollary (I hate that word, it sounds like it needs a couple of extra consonants) is that there are collections that we don’t want. I’ll give you a real example. It was a couple of years ago, I got a call about a collection of modern firsts. Sounds great, I said. All in fine condition, she said. Even better I said (secretly thinking that the collection was either wrong or her idea of fine was inaccurate). Nearly all signed, lined and dated, she said. Alarms bells started ringing (if a quote from the book is so vital to the resale value, then it ain’t that rare). She sent the list. I looked through it, all post-Harry Potter young adult type books, super-hyped and now worthless. I told her that I wouldn’t be able to buy the books. She replied telling me that she would take any sensible offer. I suggested £250. She replied that she wanted to get at least some return on the £12,000 she’d spent. I didn’t actually want the collection, I just thought that I’d pull a few out for reading copies for our daughters, and do the rest as a single lot - take a chance I thought…£12,000 would’ve been taking a chance, if that chance were zero.

That was a collector we’d disappointed, but she’d bought the books without due consideration, she all but admitted this on the phone telling me she’d seen what Harry Potter had done and thought that if other people were paying that much for books that they must be a good investment. The thing is, they weren’t Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. They hadn’t appreciated over five or ten years, none of them had. And I mean none. There were certainly some books in there that would appreciate, just not yet, not for a long time.

The other reason I’m telling you this is that collecting for investment polarises the market. When an investor buys a book for £100 some part of them is thinking about the resale value. This is fine, as a collector I sometimes do that, most collectors don’t have unlimited funds so it’s natural with expensive purchases. However, the one thing that’s better than thinking about the potential value is thinking about the purchase price. If you think the £100 book is an investment and is going to increase in price to £200 over the next few decades, then even better, pay £50 and you’re not only quadrupling, you’re hedging.

That’s fine too, get yourself a bargain. Don’t expectit from a professional bookseller, many do offer discounts, but it’s not an entitlement. And whilst we’re talking about discounts, remember that you don’t buy from a reputable dealer to get a bargain, you work with a reputable dealer to build a relationship. Believe me, constantly haggling on price or expecting a huge discount will put you to the bottom of a dealer’s list when they’re trying to place a book.

The price isn’t an issue really, the problem is the demand for non-highlight titles. An author’s lesser-known works have a lower demand than their popular, highlight items. This has always been the case, The Day of the Triffids has always been more expensive than Jizzle, it’s a better book (it’s not better than The Chrysalids though). But Jizzle shouldn’t be ignored (weirdest sentence I’ve written this week). If you allow the potential future price on a purchase to dictate your decision, then you will end up with a fairly mundane collection. Of course I’m a bookdealer, I’m going to say that right? I want to sell you all my junk that nobody else wants. Not really, to be honest, we sell the lower demand items just as well as the higher demand items. Thankfully, the investor-collector is still a minority, most of our good clients want the stuff that’s impossible to find, some of it we’ve never even heard of. I’m not writing this to bemoan the investor-collector, some of them are great, I’m writing this to highlight the pitfalls.

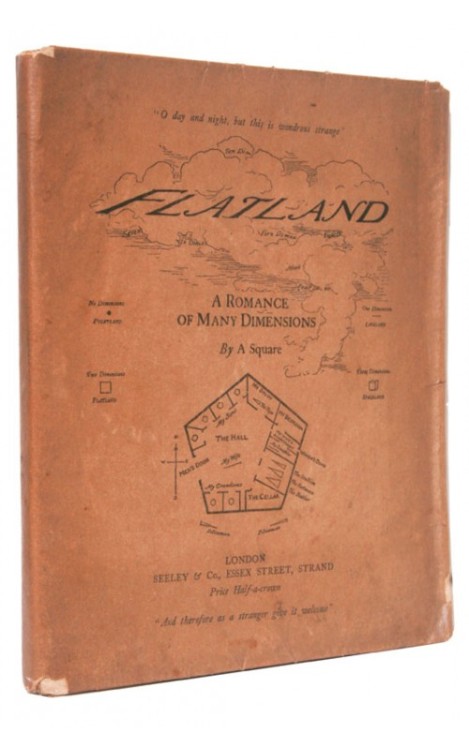

Fig 3. Currently in stock, possibly undermining this article.

Which brings me onto the next point, that collecting for investment can work. But it rarely works, at least not consistently and over an extended period, without the assistance of an expert. We have a great client who buys primarily highlight items, though he does supplement this with books he likes (a little too much he thinks). When he first sent me a wants list I noticed that most of them were expensive highlights, but there were a good number that were just great books printed in high quantities. His collection will fare well. It is well rounded and though he hasn’t bought the books for future value, I’m confident that for most of them the demand will not lessen. He is an expert collecting what he loves.

Compare this to the post-Harry Potter collector who spent £1000 on some Potter-Clone-Magic-Werewolf-Powerbadger book, only to find it unsellable now at £20 and you’ll see my point. Not an expert. Book collecting is a long game, a decades long game. If you’re not an expert, find a dealer who is and work with them, but you need to question why you’re buying books if you don’t know anything about them. They won’t tell you what books are good investments and which are poor investments, most don’t care a dot for that. They will however give you expert advice on building a collection.

If not for investment, then what for? For the love of the books, the joy of the hunt, the pleasure of the possession. It’s a bizarre, barely-rational, generally-demented, passion is book collecting. Those of you who are collectors in the truest sense know this already, I’ve got you to the bottom of the article and you feel fine, perhaps even a little better about your collection. If you’re buying purely with the expectation of financial gain, then I hope I’ve given you a little insight into the potential concerns with that.

Right, anyone got a carburettor for a ‘94 Fiesta?

Now and then we get asked for advice on creating a book collection. Most of our collectors know exactly what they want to collect and how to go about it, but for new collectors it can be a difficult task.

One of the biggest sticking points, particularly over the last decade or so, is concern about getting the key titles. We were recently offered a collection of Ian Rankin books, it was a nice collection, mostly in decent shape, but lacked the key title, Knots and Crosses. The collector was looking to sell because he couldn’t justify spending £1000 or so on a nice copy, and an ex-library copy just didn’t seem right. So he planned on selling the rest of the set to finance a purchase of Knots and Crosses and taking it from there.

This is something we see increasingly; the price of collection highlights has increase hugely over the last couple of decades as the true scarcity of these items is better known through improved information access and the demand is similarly increased as their prices become more visible. We’re going to talk below about various strategies to deal with this.

Accept that Goalposts Move

Now, it’s important to note that the vast majority of collectors don’t have a goal in mind when collecting. At first, yes, most do, but as that collection grows, the goalposts move - nearly always. Sometimes this is manifest through a sell-off, where the collection is sold to finance a new one. Sometimes the completed collection becomes part of a collection and other interests take precedence (I’ve got a full set of Heinlein’sUK hardbacks, I’m going to get the US hardbacks now or I’ve got all BernardCornwell’sbooks, I might move onto Patrick O’Brian now). Most often though, the side collections and diversions take seed much earlier on, particularly when opportunity offers.

The best thing about this though, is that this is good and almost vital.

- Accepting this leads to accepting the fact that collecting is about the journey not the result.

- Accepting this lessens the impact of completion; the collection will never be complete so that missing volume isn’t asvital (tenuous point in some cases)

- Accepting this vastly improves the chances of finding books for the collection. The joy is in the chase of course not the capture.

How to Pick a Starting Point

A lot of people specialise, we have collectors who just buy Stephen King proofs, others who just buy Nebula award winners. These kind of collectors have often been through the process of deciding what they want and are acceptant of the limitations and costs. But if you don’t have a specific definition, or even if you do, our recommendations are as follows.

Build on your Interests

IfHaruki Murakamiis your favourite author, then perhaps that would be a good place to start. Write his name on a piece of paper, but nothing further. If you like modernism, write that on the piece of paper. Books with high production values, write it on the paper. Books you’ve read, write it down. The Vietnam War, write it down. Significant moments in the history of literature, write it down.

Perhaps your interests aren’t as clearly defined and you’re interested in curious inscriptions, true rarities or forgotten books. Still, write it down, but take a moment to think how those rules are defined. Books with curious inscriptions - does the inscription have to be by the author? What defines curious? True rarities - What defines a true rarity? No copies on the market, unrecorded in bibliographies? Forgotten books - Are these books that have been out of print for fifty years? Perhaps they don’t have an entry in Wikipedia? Perhaps there’s no reference online? Once you’ve produced the definition, write it down.

Maybe you want to just collection books that take your fancy - then you don’t need this list. You’re happy, your horizon is wide and distant. Guard you secret jealously.

Think About your Budget

This is one of the most important things to consider. Try not to think about what you might be able to afford in the future (it will never be enough), think about how much and how often you want to be able to able to invest (invest in the enjoyment not the financial return). Here at Hyraxia Books we have collectors who know the books they want and will pay for them over a number of months. That’s fine, and they’ve usually accepted that that means fewer purchases. Others don’t like to do that, they enjoy the buzz of the chase so would rather spend £100 one week, £50 the next, £250 a month later. They might spend £1000 over a year, and think that they could’ve got one really nice book, but generally it’s more about the chase.

For many, this is just an as-and-when - you know how much you’re willing (or able) to spend on your collection. It’s just useful sometimes to take a step back and realise that many of the expensive books aren’t out of your reach, it might just take a bit of planning.

So with that in mind, pick a handful of prices, or better still, a range of prices you’re willing to pay. It might be wide £25-£2000, or it you might have thought that you’d like to buy a book every fortnight, so your range is £50-£100. Alternatively, you might have an idea from shopping the kind of prices that you consider: £500, £750, £2000, £1500. Write them down on your paper. The range isn’t as vital as understanding budget constraints, but it helps keep your collection in check. If you’re looking around the £500 mark, £10 books might lessen the collection, and similarly, if you limit yourself to £10, then the £500 book might tower over all the others.

Vitally though, the prices are secondary to the collection. This is important. If you want to get every book written by John Steinbeck then you still might need to plan, but your range should reflect the requirements of the definition.

Think About The Books

So, on your paper you have your budget and your interests. You have to now decide how they are going to reconcile. So if you’re interest is George Orwell and your budget is £500-£2000, you are not going to get a full set of first editions in dustjackets. If your interest is Magic Realism, and your budget is £25-£250, then you’re not going to get a first Argentinian edition of 100 Years of Solitude. So how do you reconcile that?

Let’s be practical here. If-you-try-hard-you-can-achieve-anything doesn’t apply. The majority of people will to spend a couple of hundred on a book every now and then will never spend a few thousand. So to reconcile you have to add a little further detail to your piece of paper. So, if you wrote T.S. Eliot as your interest, and your budget doesn’t allow for the first edition of The Waste Land, then you need to think of alternatives, for example:

- Later editions

- First editions from other countries

- Limited editions

- Signed copies

- Copies in lesser condition

- Interesting copies

- Magazine printings

Write those things below the list, and now those editions apply to T.S. Eliot. You now don’t have a problem, well, you do, you still can’t have that first edition of the Waste Land, but even if you could, you might not be able to have a signed First Edition, and even then, you ain’t getting the manuscript.

Of course, this is entirely unacceptable for some, perhaps even for most. Later editions, second impressions, jacketless copies are simply unacceptable to some. In that case, you need to think about payment plans or be incredibly diligent in your searches.

Think About the Scope

So, you’ve written down your list of editions to satisfy your interest in Iain Banks, but your conclusion is that you wouldn’t be happy with a US first edition of The Wasp Factory where the others are all UK first editions, and your wife or husband won’t let you spend £50 a month for the next six months. This is when you start to widen the scope. If you collect all the other books, but are lacking The Wasp Factory, then you’ll be sitting with an incomplete collection until finances improve, a bargain comes along or the spouse is silenced. So widen the scope a little from the off. Perhaps it’ll include Banks’ science ficiton novels, perhaps it’ll include proofs, or interesting signed copies. Maybe you’ll increase the scope to include other Scottish writers, or similar books / authors you’re interested in. Having a larger set of books that would fit in your collection means that you’ll always be further from completion, which sounds bad, but it means that you can always improve your collection and you’ll be happier with it.

Our own personal collection approaches the scope from two sides to try and approximate a good plan. It’s essentially a cross-section of Speculative Fiction. I love Haruki Murakami, I’ve had all his first editions, all his limited editions, all his deluxe editions. I got a copy of Sleep, one of 45 copies only to read on the colophon that there 15 additional reserved copies that I was very unlikely to get hold of. It’s also a £3000-£4000 book. These two facts told me that I would not be in a position to complete a Murakamicollection, not for a while anyway. So I would be looking at an incomplete collection, but not incomplete in a good way, incomplete in an irritating way. So I sold some of it as our first catalogue.

I still like Murakamithough, and he still needs a place in our collection. So we restricted ourselves to four of his books. And as our collection is a cross-section of Speculative Fiction, they have to be speculative. So for us personally, four is key. I don’t know why four, it just seemed right for us. So I got my piece of paper and wrote Speculative Fiction on it (actually a spreadsheet). Then I created a dozen boxes with four entries. The first box said Murakamiin it, the second said Robin Hobb, the third said Magic Realism. At that point, the collection had blown wide open. The cross-section wasn’t just authors any more, it was genres and categories. The next box was Edwardian Weird Tales. Now we were getting specific, but to me the definition of our collection was coming into focus; it was a description of speculative fiction right across the board, from the earliest stories to the most recent. Each area of the genre was to be represented by either four key or interesting titles, authors or oeuvres. Once the oeuvres were included the scope was enormous. I wrote Greek Myths in one box. Now the scope was ridiculous, but completion was in sight, and could even be surpassed. Take one section for example, Cyberpunk. Not a huge fan of Cyberpunk, but I like it in our collection. I need to pick four books, not even key titles; there are more than four key titles so it’s just a representative selection. We added a signed copy of Neuromancer, UK first edition. The key title, as good as it gets (actually not, a proof would be nicer, or a copy inscribed to Bruce Sterling…manuscript?). Book number two hasn’t been bought yet or decided. It could be the Nov 1983 issue of Amazing Science Fiction Stories (though that doesn’t fit with our budget requirements). Snow Crash? Yep, it has to be Snowcrash, maybe I won’t get the Bantam first edition at the price I want, so maybe we’ll go for the Subterranean Press edition from a couple of years ago. The point is, the books that could make it into our collection are many more than there is room for. And maybe in a few years I’ll upgrade that Sub Press edition, maybe I’ll stretch it to five books.

A final word on scope, is that as the boundaries of your definition become more and more vague, your collecting becomes much more fun. Start to include ephemera, prints, meta-works, anthologies etc.

Think About Condition

You will hear it from everyone condition, condition, condition. It’s the collector’s equivalent of location, location, location. I’m sure if we had some tedious, uninspired TV show that’s what it would be called. But as anyone who’s moved house knows, location is just one factor. Condition’s important, always go for the best that you can afford…no always go for the best that works within your budget. Yes, a fine copy will increase in value a little quicker than a very good copy, and may be easier to sell. But I wouldn’t worry too much if it’s so restrictive that it affects the balance of your collection and collecting. Does that copy of Dr. No have to be fine? Are you happy spending a little less and getting a copy of Thunderballas well?

Learn When to Say No

Even if your funds are limitless, and some essentially are, you still just don’t want to amass. Amassing dilutes the collection, it lessens the highlights and achievements. If you find yourself in the position of buying 200 books from a friend who has lost interest in collecting books and has moved on to coins (I shudder at the thought). Then buy them, treat yourself to those you really like, those that fit in with your definition or those that offer a new branch that you really like. Get rid of the others. Sell them to a dealer, take them to auction, or just put them in a box in the loft.

If you don’t, you’ll end up losing sight of the (ever changing) definition. It will lessen the impact of your own collection, particularly if some of those books surpass your treasures in terms of value and / or prestige. Of course, like I say above, this might be an opportunity to expand your definition and that’s fine, but you need to think it through.

Collections Can Shrink

Book collecting is a long game, it takes years, a lifetime, several lifetimes. Your tastes will change, as will your budget, as will the market. Keep this in mind because some of your treasures will lose their appeal, some will lose their value. There’s nothing wrong with trimming off the fat now and then. Similarly, if you have a copy that’s a little poorer than you’d like, maybe missing a jacket or even an ex-library copy. Maybe you loved Colin Dexter when you were forty and it was on the TV. When the time is right, sell it. You might make a loss, you might make a profit.

The important thing is that you don’t let books stick around when they no longer fit the definition, or if they just don’t suit. I do this as a dealer, I usually price faded copies quite low because it’s my bug bear. They stare at me on the shelves - they have to go.

Don’t take this too lightly though. If you have a nice Brighton Rock in dust jacket, that just no longer appeals to you, bear in mind that it might take a couple of decades to get another copy.

Ignore the Above

Ok, that works for me, it works for a lot of our collectors. But for many people, increasing the scope, or removing edition restrictions totally undermines their collection. In that case, keep your definition tight, buy just exactly what fits that definition and ignore what I’ve said.

A Word About Investments

If you look at the selling prices of many books from 20 years ago, and compare to now, you will immediately be aware of how wealthy you could’ve been. Similarly, if you look at the results of the last 20 FA Cup Finals, you will be immediately aware of how wealthy you could’ve been. Don’t collect with a view to getting a decent return. It might happen, it might not, some books will go up in value, some will go down. Collect for the chase, even if that chase is for a bargain.

Having said that, do bear in mind that the vast majority of books will be worth much less than retail price in the future. Salman Rushdie’sFury will never be worth more than £10-£20. Even if his next book is better than the Divine Comedy,Fury, will always be a cheap books. There are thousands of them. Having this in your collection might be necessary, but understand it’s value - it’s not a financial investment, it’s part of a collection.

Midnight’s Children on the other hand, the Booker of Bookers. It’s already expensive, but surely it’ll go up in value? Right? Maybe. The Booker prize might cease in 2025, and fade into obscurity. But it’s still a good book, a great book, it’ll always be remembered, right? Maybe. Lots of great books have been forgotten, lots of great books are cheap.

If you’re concerned about a return on investment, take into account the scarcity, market values, copies on the market, time on the market, quality of the writing, significance of the author to literature in general, significance of the book specifically, anything unique?

Conclusion

So, what’s the conclusion? Well, this isn’t a cover-all type of situation. It’s more of a way of mitigating the concern that you’ll never get exactly what you want. Every collection is different, every collector has their own method and motivation and most collectors probably accept this already. Sometimes it can be fun to relax your definition a little, or to have a think about approaching your collection from a different angle. For us personally, we started many moons ago with the notion of being completists; it was never as fun as it is now.

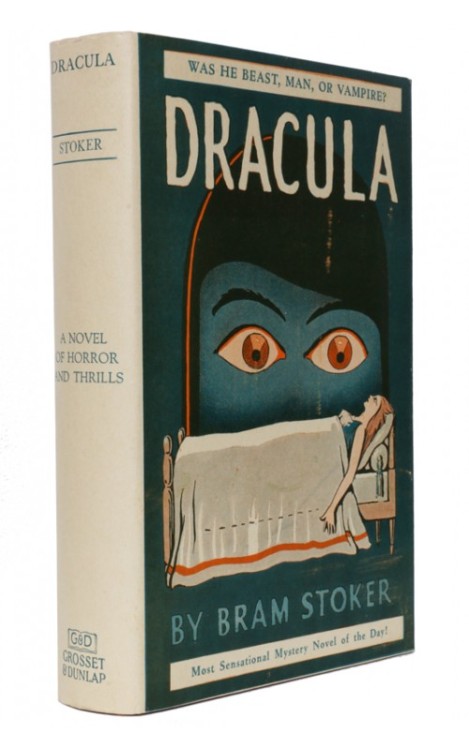

Dracula, by Bram Stoker. A 1927 edition published to tie in with the first Broadway production. The novel was presented at the Fulton Theatre, directed by Ira Hards. The present copy is an exceptionally well presented copy, in a fine dust wrapper.

Post link

I was looking through the shelves thinking which book to write about next and I came across Stapledon’s Star Maker. I’d read it recently and it’s a remarkable book (rather, it’s an ongoing read*). I thought it wouldn’t be suitable as it was re-published as part of Gollancz’s SF Masterworks series, I thought it was still culturally significant. Yet, looking through a number of ‘greatest science fiction’ lists (I know I shouldn’t do that). It was notably absent, even from Pringle’s list. Looking through the NPR list World War Z was in the top 50, but no Stapledon. Anyway, I’m not here to rant on relative merit, I’m here to talk a little about a classic work of literature that seems to be slipping.

So, a little about the author. Stapledon’s known as much for his academic work as for his fiction writing. His earliest academic publications were in the realm of philosophy and psychology, though these were preceded by a couple of volumes of poetry from 1914 and 1923. his philosophical ideas around society and community passed through into his fiction, starting with Last and First Men of 1930. Stapledon’s works was read by many of the next generation of SF writers.

Star Maker itself was highly acclaimed by a number of contemporary writers including Woolf, Wells and the outstanding Borges. Arthur C. Clarke is noted for having been highly influenced by the novel. Within the first few pages, Stapledon does something I absolutely love in science fiction; he dismisses entirely the science. We’re taken on an odyssey to the edges of our galaxy with no mention of the method. That’s not to say the science is lacking, Freeman Dyson’s Dyson sphere was based in part on Stapledon’s idea. His discussion of a collective mind is also quite a forward-thinking idea for the time.

It is a tricky book though, I had to rest after the first few pages because the overall feel of the writing is quite colourless - it reads more technical than dramatic. However, given the breadth and depth of ideas therein it is certainly an important milestone in the history of speculative fiction, particularly as it exists in that hinterland between the birth of science fiction and it’s full flowering.

The book was published on the 24th June in 1937 (initially intended to be the 10th) by Methuen. The first issue is identified by having blue boards with red lettering. Here’s a link to our copy of the first British edition in the Bip Pares jacket: £2750

* The ongoing read has been something of a habit of mine for many years, but only recently have I structured it into my reading habits. I figured that a novel is on average 250 pages long. I figured a short story is around 20 pages. One novel is roughly equal to around 12 short stories. I find it difficult to sit and read a full book of short stories. So here’s how I structure it; I read a novel, then 12 short stories (or novellas etc). But rather than read 12 stories by one author I read 12 stories by 12 authors. So the last iteration in the cycle was: [Novel] Ubik, [Shorts] Grimm’s Fairy Tales, J.G. Ballard, H.P. Lovecraft, Sophocles, Neil Gaiman, Arabian Nights, John Milton, Virgil, Malory, Asimov, E.T.A. Hoffman, Ray Bradbury. Anyway, just thought I’d share because it works for me!

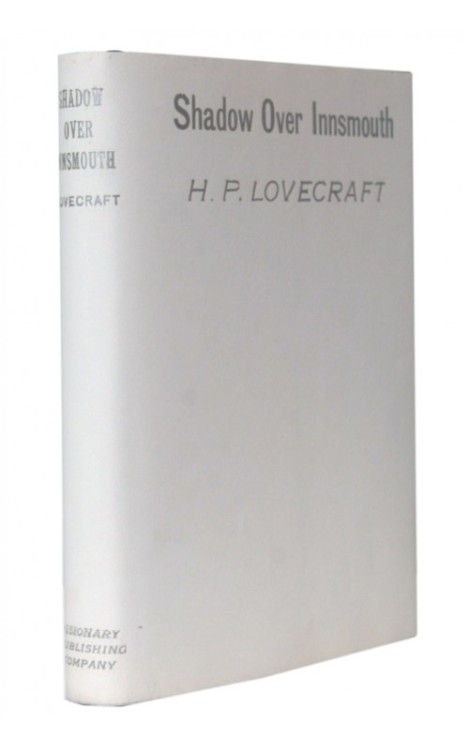

Everett PA, Visionary Publishing Company, 1936. Hardback first edition and first impression. Fine book with a little dustiness to the boards and a wrinkled spine (this is due to poor production quality and is as published). The jacket is fine (many were issued following publication, hence why it’s not uncommon to find very nice copies). One of only 200 copies. Single page errata sheet included.

Post link

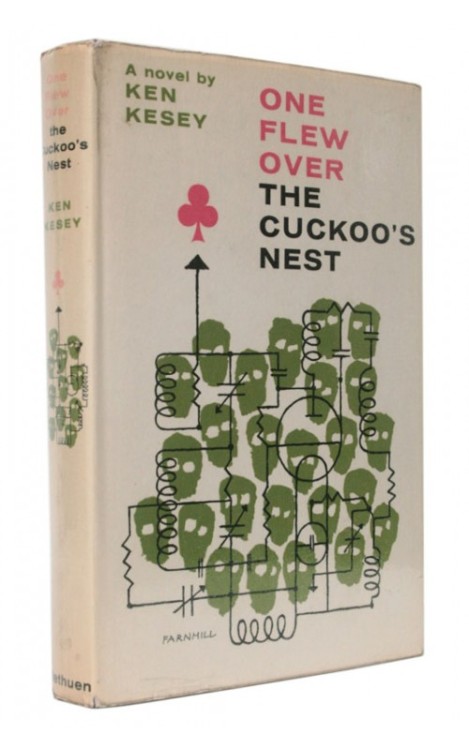

Ken Kesey - One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest - Methuen, 1962, UK Signed First Edition

London, Methuen, 1962. Hardback first edition and first impression. Inscribed by the author “For / Erik / Kese”. The signature is accompanied with Kesey’s Totem Stamp. A near fine book in a very good jacket. Some bumping to the spine tips. Jacket spine with some browning. Two small punctures to the rear, probably from a staple, passes through jacket, lower board and a couple of gatherings. Generally decent with a little ageing. Jacket designed by Kenneth Farnhill. A highly-challenged and regularly banned book, best known for the five-times Oscar award-winning film.

Post link

A new collector got in touch recently to ask our opinion on an inscribed book. He was concerned because the book was signed to someone else. I pointed out the various merits and flaws with the different types of signatures. It seemed apt thereafter to share this on our blog.

Signed or Inscribed

This is an oft mentioned argument. A signed book is one where the author has scrawled nothing but their name on the book. An inscribed book on the other hand usually carries the name of the recipient in the author’s hand [often an inscribed book will just carry a greeting without a name]. Of late there has been debate about the various merits of the two types of signature. I’ll outline below the merits of each.

A signed book

An inscribed book

An inscribed book is usually signed to someone else and carries their name. People often find this less than desirable because every time the owner examines the signature they are reminded that the book isn’t signed to them personally. This is just a facade of course, as a book purchased signed or inscribed has no connection with the purchaser anyway. But it is easy to see how the anonymous signature could be preferred. That being said, here at Hyraxia, we believe the more ink on the page the better. If a collector looks to buy only books signed without an inscription then they are often dismissing inscriptions that could have merit of their own; even a few brief words can give a deep insight into the author’s manner and make an ordinary book something special.

A book inscribed without a name.

Of greater significance is where an author signs without inscription by default. In these cases, such as with Graham Greene, an inscription is preferred. These signatures are both scarcer and more collectable as Greene generally inscribed books to people he knew.

The final point to consider is forgeries. A forger is less likely to risk exposure by writing an essay on the title page. That said, an expert forger will likely find it easier to dupe a buyer if they inscribe the book too. Either way, there is more room for error in an inscribed book than a signed book.

Presentation Copies

Presentation copies are often preferable to a regular signed copy particularly if signed by the author. Presentation copies are books signed and presented at the author’s behest, not the recipient’s request. This is significant because they are often scarcer, but also because there is an implicit, if somewhat forgotten or hazy, connection between the recipient and the author.

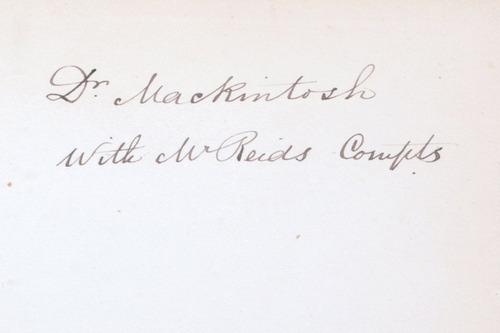

A presentation copy signed on behalf of the author

We mentioned above that presentation copies are preferred, with the caveat of them being signed by the author. Wealthier or busier authors would often have a secretary or publisher sign a presentation copy on the author’s behalf. One should always be cautious when considering a book signed ‘with the author’s compliments’ or similar. This is often autographed by someone else, but still collectable. Earlier books were often signed in this manner, seek advice from an antiquarian or rare bookseller if you’re unsure.

Association Copies

Anassociation copy is generally the best state of a signed book. An association copy is a book that has been signed by the author and subsequently owned by someone with whom there is an explicit connection to the book or author. These can be books signed by the author to a relative or friend, someone well known in particular other authors, people involved in the publication or people associated with the content of the book. It is always important to seek further provenance for association copies. A book signed “from Roald to Quentin” seems likely to be for Quentin Blake, but one must assess this based on evidence at hand – ask a Roald Dahl specialist if he ever signed books to Quentin Blake.

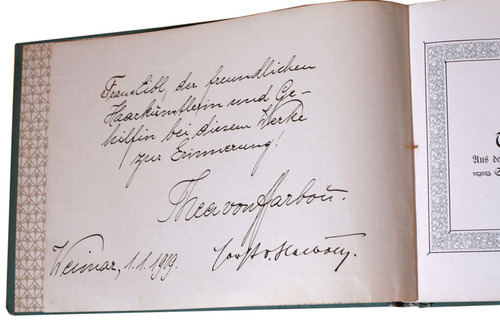

An association copy from Thea Von Harbou to her Hairdresser

An association copy from Asimov to Brunner

One can also find association copies that are unsigned, these are still desirable in their own right.

Dates

Often authors will write a date beneath their signature. It is generally accepted that a date closer to the publication date is preferred, primarily because this implies that the book was signed close to the publication date. Collectors prefer earlier signatures for two reasons: firstly, there’s an implicit connection to the book’s publication – in the same way first editions are collected, there’s a desirability to collect things in their earliest appearance; secondly, early signatures are often scarcer and more attractive as authors are less well-known and take a little more time and care over the signings.

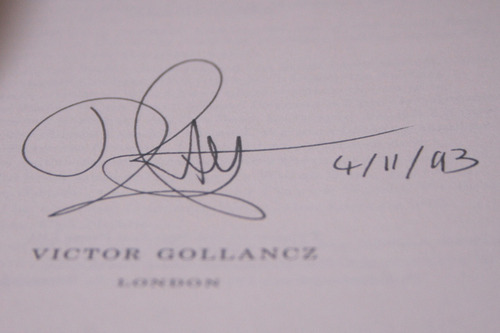

A book signed and dated (in this case prior to publication)

Often one will see signatures pre-dating publication, these are usually where an author has signed a batch of books for a shop prior to publication, but there are some books where the pre-publication date signifies a presentation copy; the books have come from the author’s personal allowance.

Signature Age

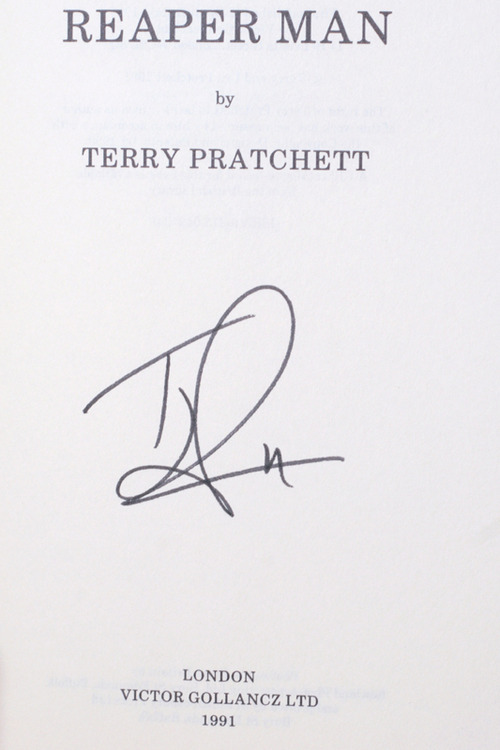

As authors age and attend more and more signings it’s not uncommon to see their signatures change, as noted above. The classic example is Terry Pratchett whose signature shifted from a full forename and surname in an attractive scrawl to what is essentially a symbol. We recently handled a collection of signed Pratchett books each of which held a contemporary signature and the progression was quite obvious. The early signatures are scarcer and indicative of a contemporary signing.

A recent Pratchett signature

An early Pratchett signature

Other than scarcity and desirability, one can also use signature ages to determine the authenticity of a signature. A copy of Pratchett’s latest book with an early signature is highly unlikely, and should be viewed as suspicious.

Bookplates

Bookplates come in a variety of forms and from a variety of sources. The least attractive arrangement is when a book is sold with a signature ‘laid in’. Oftentimes the signature will be on a scrap of paper, a publisher’s bookplate or a generic plate. There is no implicit connection between the signed paper and the particular copy of the book. This is simply something that the seller has put together to make the sale more attractive. This particular arrangement can, in our opinion, be worsened when the plate is pasted down by the previous owner.

A publisher’s bookplate (pasted in by the publisher)

Sellers do sometimes sell books and signatures in this format for the legitimate reason that they were purchased in that fashion and therefore the connection between the two is created through the provenance.

There is an exception to this rule when the book is published or sold in that particular state. For example, we have in stock a set of Philip K. Dick’s Collected Stories that were signed by way of a signature strip from a cheque. We also have a Murakami limited edition for which the publisher sent the author a group of plates to sign for the limited edition, which the publishers then pasted in. This is common with limited editions. An edge case is when a bookseller requests a number of plates from the author or publisher and then sells them on. We find that these are generally less preferable.

A book signed by way of a cheque (also a presentation copy)

Finally, bookplates are much easier to forge. There’s no risk of damaging a rare book and mistakes can just be binned. We’ve even seen high-quality photocopies of bookplates.

This is of course a matter of taste, but with regard to collectability one should opt for a book signed directly to the bound page or as published (in the case of tipped in leaves).

Scarcity

The final thing we’re going to look at is scarcity of a book in a signed state. If you find that you have the opportunity to be particular about the manner in which a given book is signed, then the chances are that signed copies are not particularly scarce on the ground. The phenomenon of ‘books with added value’ seems to be fairly recent borne most likely from the Harry Potter craze. Publishers wanted to create the next Harry Potter, collectors wanted to buy the next Harry Potter. The publishers printed first editions in huge quantities because the demand was there. Out of the high demand came a demand for collectable copies. Limited editions (both from the publisher and the bookshop) became more common, but also did books with various additions. By various additions we mean signatures from the cover artist, illustrators, and all manner of people associated with the book, additional sketches, dates under the signature and the recipient’s favourite line from within the book written by the author, ephemera from the publication including posters, bookmarks, postcards, bags and all manner of things. The publishers plough so much into marketing the book that the authors do huge tours where before there might be only a couple of signings. So the first editions are signed in huge numbers and are not rarities.

Signed, with a date and line from the book.

Our recommendation with these type of books is to err on the side of caution. You need to ensure that you’re buying for desirability and not for value because there’s a very good chance that you’ll be overpaying. One also has to understand how much value that embellishment actually adds to the book.

Quality

Byquality I mean the actual standard of the signature. Collectors will often prefer a signature written in a nice pen and not in a hurry. It’s easy to spot a sloppy signature.

Provenance

The stronger provenance you are offered the better chance you have of being secure in your purchase. Provenance doesn’t mean a good story to go with the book, it refers to evidence supporting the book’s reported history.

The important thing to note with provenance is to not be fooled by it. We were recently offered a signed T.S. Eliot book, the book was presented with a letter of provenance. It was a great story, the dates and association all lined up, there were associations with editors of magazines that Eliot wrote for and the names on the inscription all were accounted for – even the date had corroboration. However, the signature felt wrong as did other signatures for that the seller was offering. It was such a complex ruse too that holes appeared. The point is that it was so confidently presented that it was difficult not to believe the provenance.

Limited Editions from the publisher are pretty much guaranteed to be authentic, but are not always more valuable than signed first editions, particularly when printed in runs of 1000 or more. The provenance here is inherent.

A signed limited edition

Things such as ticket stubs, photos of the signing or promotional material can help, but these are not a sure fire way of guaranteeing an authentic signature. Of late, holograms have been used to authenticate a book as holograms are difficult to forge. While this pretty-much guarantees that you’re getting an authentic signature, it also suggests that the book was signed at a mass-signing, which to some extent reduces the desirability.

A hologram

Similarly, a history of the book at auction, doesn’t guarantee authenticity, but it does suggest that someone with a great deal of experience has looked at the signature and deemed it authentic. The same can be said with Certificates of Authenticity. These vary from a hand-written note guarantee to a full-blown holographic certificate from a reputable company. All the latter says is that someone has deemed the signature authentic and perhaps even guarantees that should it be proved inauthentic the buyer will get their money back. The problem is that it’s very difficult to prove a signature inauthentic. Often, experts in the trade will be asked their opinion to examine a purported forgery, which brings me back to my point of asking a member of the trade in the first place.

Another good bit of provenance is catalogue descriptions of the book’s previous sales, or receipts etc. from a previous seller. This chain of sales constitutes a good bit of provenance and again shows that experts have examined the book and deemed it authentic.

Manydealers will help you examine a signature, but the best way to attract these services is by becoming a customer and creating that relationship with the seller. You then have someone you can rely on for help and advice, who in turn can refer to their colleagues in the trade.

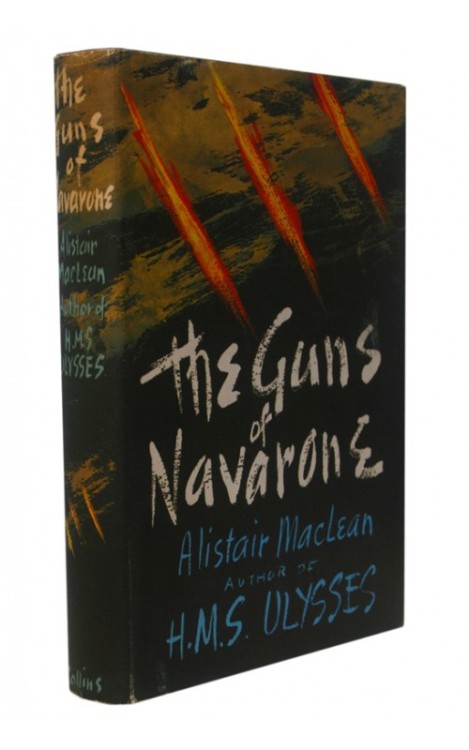

Alistair Maclean - The Guns of Navarone - Collins, 1957, UK Signed First Edition

London, Collins, 1957. A fine copy with a short closed tear to the top of the jacket only a few mm. Some light edge wear and a slight lean. Signed without inscription by the author.

Post link

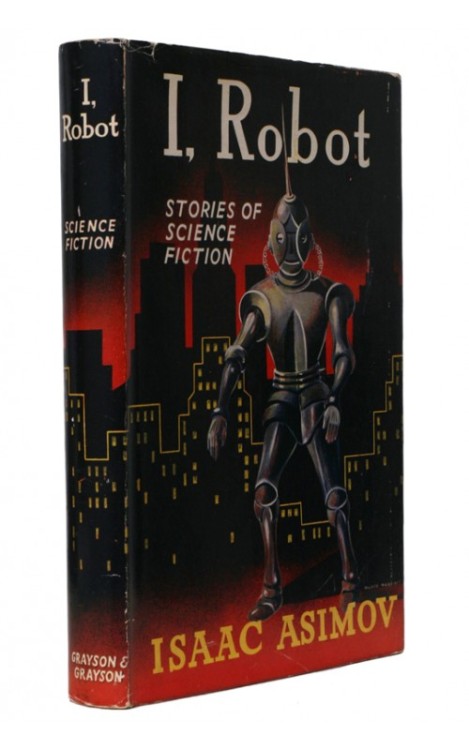

Isaac Asimov - I, Robot - Grayson and Grayson, 1952, UK First Edition

London, Grayson & Grayson, 1952. Hardback first edition and first impression. The book and jacket are near fine. Owner’s stamp to front end paper, owner’s plate to title page (covering owner’s stamp). Some soiling to page edges. Jacket is near fine also with a couple of neat closed tears, and a few creases. A very nice copy.

Post link

Thea Von Harbou - Metropolis - August Scherl, 1926, First Edition

Berlin, August Scherl, 1926. First edition in wraps. A fine copy with light edge wear and some toning / spotting to the rear. Eight plates featuring stills from the film and a cover illustration from Willy Reimann. An exceptional copy.

Post link

David Gemmell - Legend - Century, 1986, UK First Edition

London, Century, 1986. First hardback edition and first impression. A Fine copy with a slightly toned page block, flaps have a little creasing to the inside. Legend was Gemmell’s first published book, being originally published in paperback. This is the first hardback edition and Gemmell’s most collectable work. Gemmell passed away in 2006 and has firmly established himself as one of the strongest writers in the genre. This book is the most collectable of the Gemmell books, and a highlight of modern fantasy first editions. An important book.

Post link

damn is there no way to buy physical EDA books anymore ? :( like i know i can just read them for free online but i just think they would be rly fun to have

I’ve just checked a few on UK Ebay and people are selling used copies. Some are really expensive, others are a few quid per book.

Currently scrolling through Ebay to see my choices

Check out doctorwhostore.com via the small scifi/fantasy nerd business alienentertainment. They have quite a few EDAs there, including some I’ve not been able to locate elsewhere. Lots of VNAs, PDAs and MAs and other Who merchandise as well. Amazon also had a number of different small booksellers to acquire from. Good luck and happy book buying/reading :)

Also try Addall it’ll search 20+ book sites simultaneously, including foreign sites! It doesn’t include the shipping cost in the price sort (as it doesn’t know where you are) so make sure to look at multiple shops in the price range as the shipping may vary wildly.

Of the sites it commonly pulls from, I suggest ordering from Biblio for anyone needing a book shipped from the US to the UK, EU, or Australia. I am a book dealer by trade and recent changes with imports and VAT mean that a lot of the sites have Trouble doing it right (looking at you Amazon). Biblio gets it right and makes it easier on the dealer’s end to GET it right. so if you see a dealer with same book listed on multiple sites, pick Biblio to order from as being the one least likely to end up with your book stuck in customs.

Some new books from one of my favorite publishers, Cluny Media.