#rare books

Spotted in the stacks: this scavenger hunt in the pages of Wilson Library’s copy of The whole treatise of the cases of conscience, distingvished into three bookes (1632). At first, these reader annotations (by former owner William Gasker) seemed like a normal treasure hunt until I realized:

1) The hunt leads the reader in an infinite loop

2) The page numbers didn’t match up with the actual pages I turned through. Turns out, this was because the pages were bound out of order! (Page order was actually 96, 101, 102, 103, 104, 97, 98, 99, 100, 109, 110, 111, 112, 105, 106, 107, 108, 113, 114, 115)

Not sure if this weird scavenger hunt is the annotator’s way of drawing attention to the misbound pages or if the scavenger hunt actually leads to a huge Da-Vinci Code-esque revelation if you use some sort of top secret cipher.

Intrigued? Come visit Wilson Library and solve the mystery yourself!

Post link

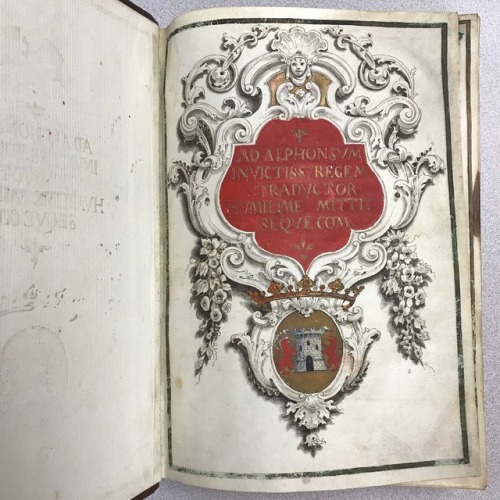

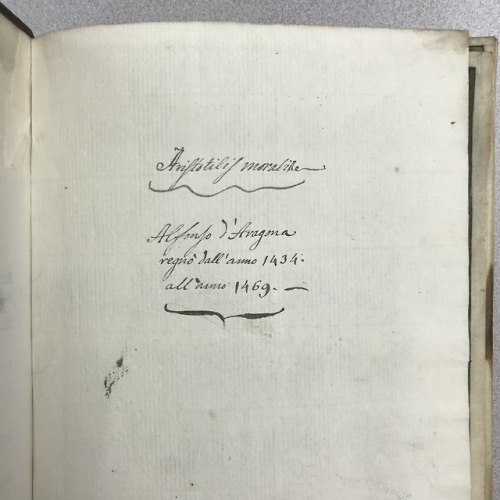

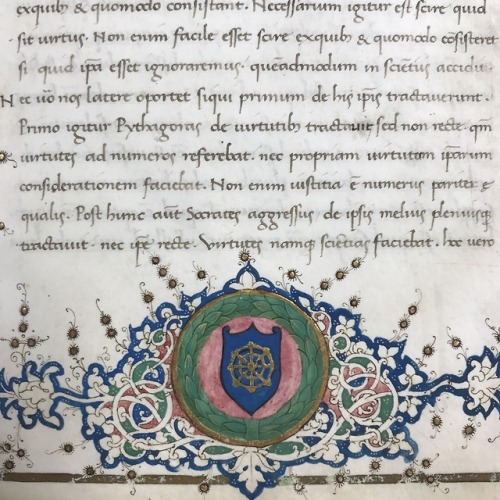

Our rare book catalogers are nearly finished cataloging this rare and elegant copy of Giannozzo Manetti’s translation of Aristotle’s Magna moralia and Eudemian ethics. Only four other copies are known to exist.

Post link

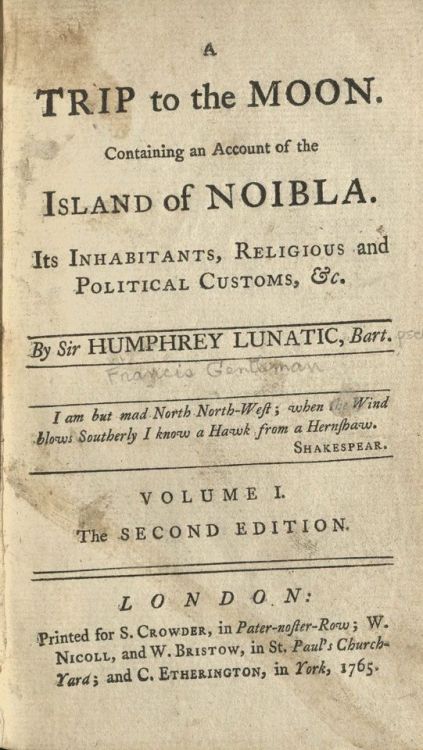

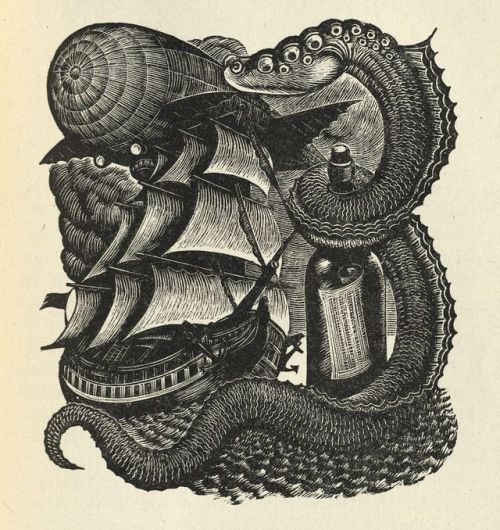

Space Spiders, Lunatics, and Airships : Moon Voyage stories in Wilson Library

It’s a full moon tonight, so we thought that it would be a great time to feature our favorite moon voyage story in Wilson Library Special Collections–the only problem is, we couldn’t decide between these three amazing narratives! So we need your help, Tumblr followers! Read below, and help us decide which contender is the ultimate sci-fi adventure!

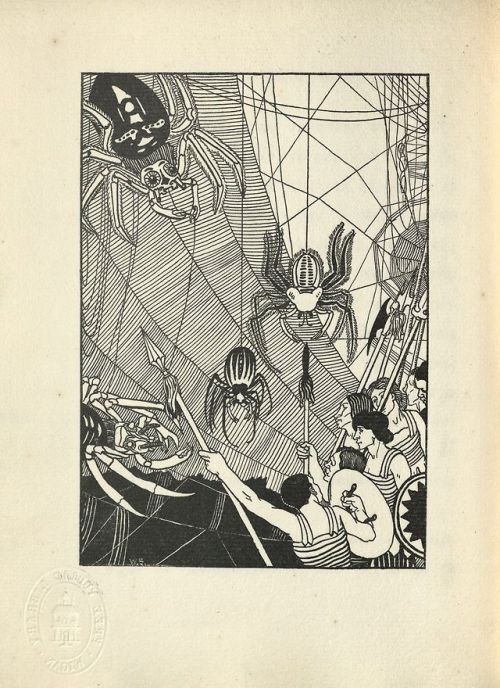

Contender 1: One of the earliest recorded moon voyage stories, Lucian’s “True History”was written in the second century AD in ancient Greece. This “true” history is filled with fantastic travel narratives, including the moon-voyage adventure in which a crew accidentally lands on the moon after their ship gets carried into the sky by an enormous gust of wind. The men then take part in a fantastic space battle between the alien armies of the sun and moon. (Bonus points: the space battle features giant spiders who spin web-bridges to lead their army across the sky).

Contender 2:A Trip to the Moon (1765) was written by sir Francis Gentleman under the very appropriate pseudonym, Humphrey Lunatic. In this story, Humphrey falls asleep in a beautiful grove and (much to his surprise) wakes up in the Lunar world. How does he get transported, you might ask? The pamphlets in Humphrey’s pockets (which were, apparently, originally conceived in the Lunar kingdom) attract a tractor-beam that pulls Humphrey up towards the moon. Full of tongue-in-cheek humor, this story is memorable both for its whimsy, and for its cutting social commentary. (Bonus points to Francis Gentleman for both his amazing pen name, and also for including an elaborate family lineage for the “Lunatic” family that includes an ancestor named Whimsical Lunatic, Esq.).

Contender 3: Last but not least, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfall” (1835) features a slightly more technologically advanced means of conveyance. In this story, the protagonist takes an airship to the moon. Not only is this story an interesting moon-voyage account in its own right, but in addition, it was in fact, originally created as a hoax. Shockingly, Poe’s tale was not the only moon hoax of 1835, but was second in renown to the “great moon hoax” of the same year. In this moon hoax, the New York Sun (a tabloid newspaper) published a series of articles on fake “celestial discoveries”–which included the discovery of a species of intelligent lunar bipedal beavers. (Bonus points to Poe for not only creating his moon-travel hoax, but also for dreaming up his 1844 balloon hoax–in which he convinced readers of the New York Sun that a man had crossed the Atlantic in just 3 days in a new form of airship).

Got opinions on which of these three is the best moon voyage story? Comment below to let us know your pick!

Post link

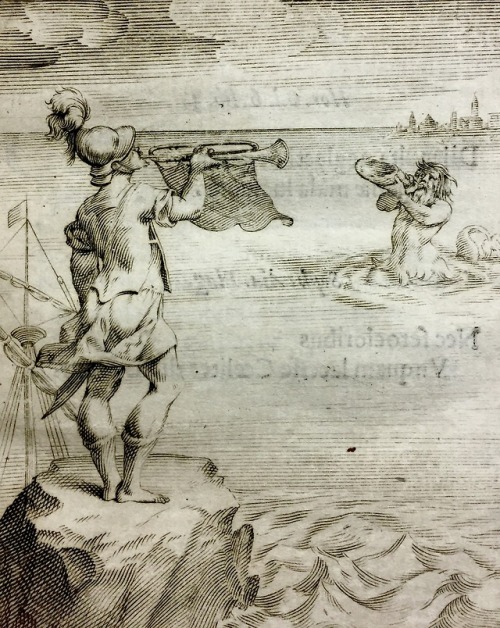

Happy mer-May from Wilson Library Special Collections!

This particular mer-man is found in the pages of Wilson Library’s copy of Pavli Macii Emblemata…(1628).

Post link

After looking through slideshows of last night’s Met Gala, I was determined to find a truly impressive outfit of the day in our special collections. But in my attempts to choose a favorite, I couldn’t decide between these three amazing hats from Wilson Library’s 1625 copy of Della novissime iconologie.

Whateveryour particular favorite Renaissance fashion look might be, it’s clear that all three of these early modern emblems are absolute style icons.

Post link

As you know, our librarians here at Wilson Library love finding all the mermaids in our special collections. So today, when we came across multiplemer-beings in our stacks, we knew we had to share them with our Tumblr followers.

These mer-men (and mer-creatures and mer-clergymen) were found in our Rare Books Collection’s copy of Physica Curiosa, a 17th century text dealing with a wide range of subjects including zoology, cryptozoology, obstetrical abnormalities, and demonology. Although Gaspar Schott includes all manner of centaurs, monster-chickens, wolf-men, and other oddities in Physica Curiosa, these mermaids are definitely our favorite cryptid of the book.

Post link

Love “The Phantom of the Opera”? Then come over to Wilson Library Special Collections and take a look at this amazing 1943 edition of Gaston Leroux’s book!

This copy–which is part of our mass market paperback collection–comes complete with a blueprint of the Paris Opera house, so you can know exactly where all your favorite scenes take place!

Post link

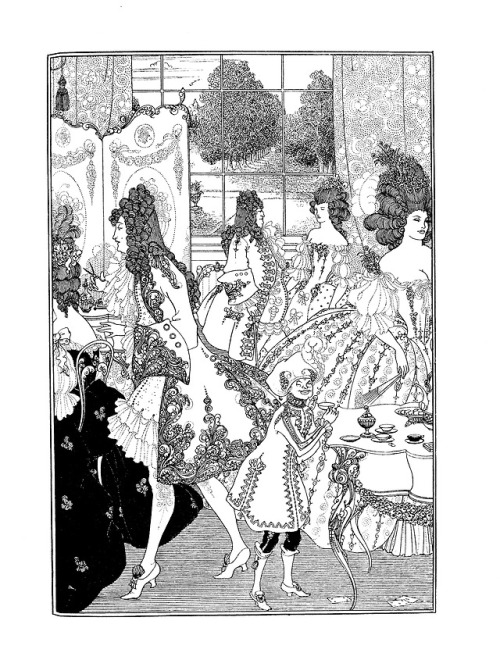

Today’s#colorourcollections post comes courtesy of illustrator Aubrey Beardsley! This ornate illustration appears in Wilson Library Special Collections’ 1896 edition of The Rape of the Lock , which combines Beardsley’s art with Alexander Pope’s mock epic poem.

I don’t know about you, but I’m very excited to color all the ruffles, wigs, and gowns that appear in this image!

For more #ColorOurCollections fun, head over to the main site (here), or to UNC Chapel Hill Library’s Coloring book (here)!

Post link

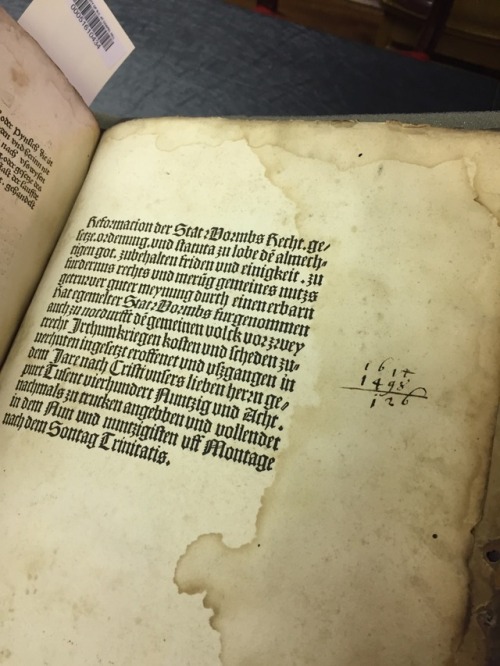

Today’s highlight from our Rare Books Collection is some charming marginalia from our copy Der Statt Wormbs Reformation . From what we can tell, the annotator was trying to figure out the time that had passed between the first printing of this text and the year 1614. However, this owner slightly bungled both the original publication date (1499, not 1498) and the math (the difference should have been 116)!

Despite those few mishaps, though, this piece of marginalia is still a favorite of mine. Although the annotation is small, this subtraction makes a nice addition to the work of anyone studying reader-text interactions!

Post link

January 1, 2018 marked the 214th observation of Haitian Independence Day, which celebrates the culmination of a 12 year struggle by self-liberated former slaves against French colonial rule in the country then known as Saint-Domingue. The Haitian Revolution was the only slave uprising that led to the creation of a state, and challenged long-held perceptions about race and slavery across the Americas.

Within our collection is Lettre des Commissaires des citoyens de couleur en France à leurs frères et commettans dans les îsles françoises, a pamphlet written by the Citoyens de Couleur en France (Citizens of Color in France) on June 10, 1791, just before the storm of revolution broke. The pamphlet, addressed to both the white and black citizens of Saint-Domingue, celebrates the French National Assembly’s decree of May 15, 1791, which extended political rights to persons of color born of free parents, and outlines the proper response to the decree. The pamphlet encourages working hard, trusting the law to take care of injustice, and treating slaves more fairly. Despite the hopes of the writers, tensions in Saint-Domingue worsened, with increased conflicts between white colonists and free black citizens, and eventually erupting in the massive slave revolt of August 21, 1791.

Post link

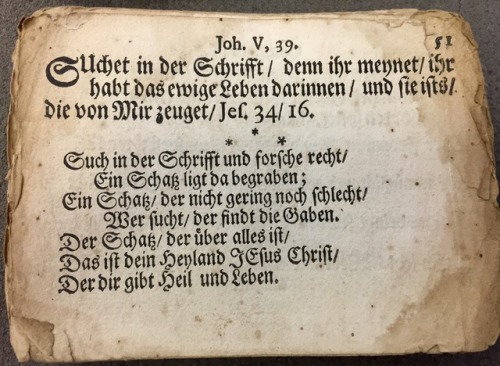

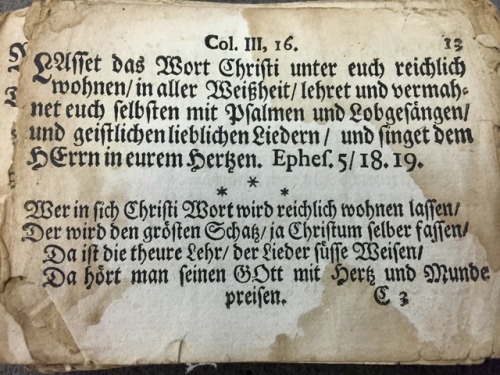

One item that is currently being cataloged for the Rare Book Collection is this early Pietist devotional work that intended for its reader to tear out its pages for personal use. This is the only known copy of the 1725 edition and there is one extant copy of the first edition from 1719 held in Germany. This rarity is likely due in part to the intended ephemerality of the piece. The Biblisches Spruch-Kästlein, or little chest of biblical sayings, is a testament to the beginnings of Pietism within the Lutheran faith. The preface argues that that the reader should not learn solely from sermons, but also from personal exploration of the Bible and its truths, pointing to the work of Lutheran theologian Philipp Jakob Spener, who is considered to be the father of Pietism. This little volume, measuring 7 x 10 cm, includes directions for use, which tell the reader to consider ripping out a particular page to read and remind oneself of spiritual truths throughout the day. Another possibility would be to read one page after the other, or to open the book at random, read the short entry, and look up the corresponding passage in the Bible for further learning. Each page includes a verse from Luther’s translation of the Bible, a reference for further reading, and a rhymed poem that interprets the verse. The poems tend to emphasize the importance of personally studying the Bible. This piece shows a move toward encouraging individual learning and devotion for both the young and old. The Rare Book Collection copy was contained in a small, portable slipcase. Most pages of the volume have been removed from the sewn gatherings and were stored loose in the case (surprisingly very few are wanting). The pages show heavy use and point to personal spiritual education in the early eighteenth century.

Post link

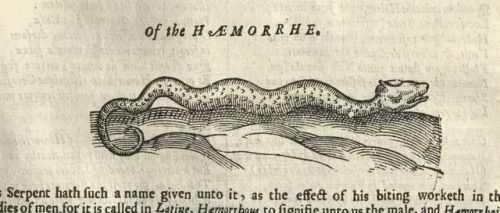

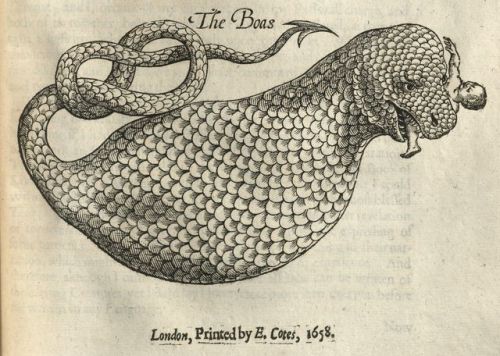

So many beautiful (and sometimes scary) beasts! From Topsell’s The history of four-footed beasts and serpents …

Post link

Fellow Andrew Keener searched through annotated dictionaries, language manuals, plays from Renaissance England to learn about multilingual readers in Shakespeare’s England.

Post link

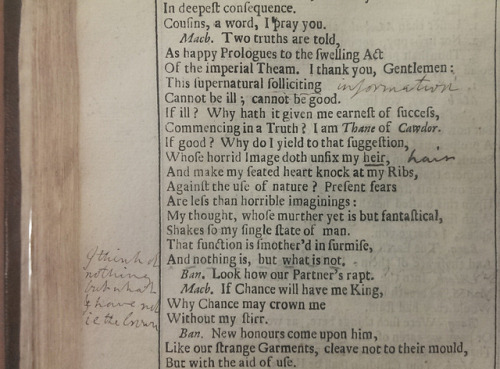

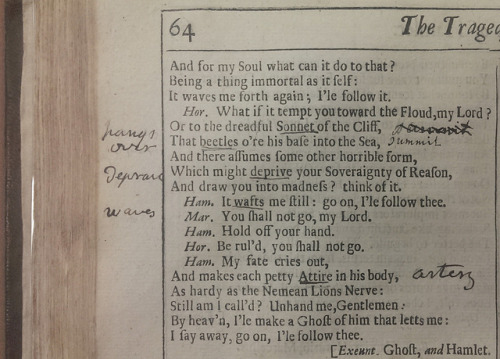

Today, April 23, is Shakespeare’s birthday! Maybe. Supposedly. It was certainly the date of his death in 1616, but it also commonly celebrated as the date of his birth, some 52 years earlier in 1564.

Several editions of the Bard’s works were printed before his death, but the most complete and most famous collections of his plays are the large folio editions, produced posthumously.

While these beautiful and rare 17th century Shakespeare folios are a significant improvement over the earlier “bad” quarto versions, they are far from perfect copies of Shakespeare’s works.

In the case of own Fourth Folio, it appears as though a previous owner sought to correct some of the numerous typographical errors throughout the volume. Our dutiful annotator has also added several marginal notes commenting on various passages in the text.

Some of these typos really change the meaning of the text in humorous ways:

If good? Why do I yield to that suggestion,

Whose horrid image doth unfix my heir [hair]

- Macbeth, Act I, Scene 3

What if it tempt you toward the Floud, my Lord?

Or to the dreadful Sonnet of the Cliff [summit]

- Hamlet, Act I, Scene 4

My fault is past. But oh, what form of Prayer

Can serve my turn? Forgive me my foul Mother [murther/murder]

- Hamlet, Act III, Scene 3

All those bored scholars with nothing better to do than overanalyze Shakespeare’s works looking for hidden messages should have a field day with some of these passages.

Post link

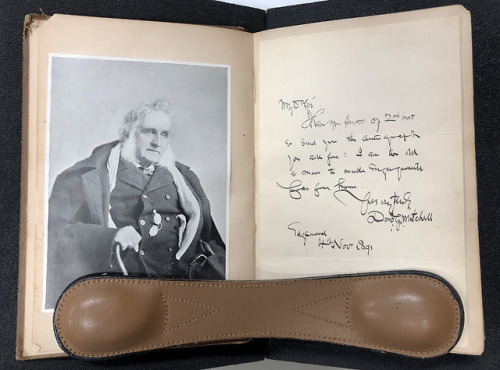

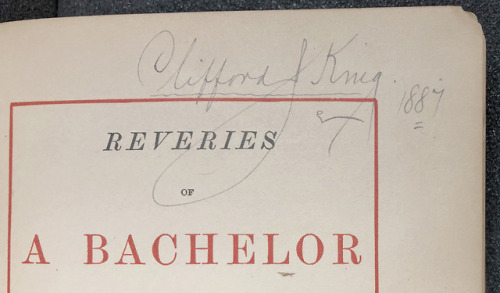

Reveries of a Bachelor

Though very few modern readers would recognize the name of Donald Grant Mitchell, his collection of sentimental vignettes, Reveries of a Bachelor (written under the pseudonym “Ik Marvel”) was one of the most popular novels of the Victorian era. It was a favorite of Emily Dickinson, and has even been compared to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in its popularity and influence.

Aside from serving as U.S. consul to Venice from 1853 to 1854, Mitchell (1822-1908) spent much of his career writing at Edgewood, his estate near New Haven, Connecticut. Portions of Reveries of a Bachelor first appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1849, and then in 1850 it was published in book form, going through dozens of editions in the following decades. Excerpts were even reprinted by insurance companies and the makers of tonic medicines to be distributed to potential customers.

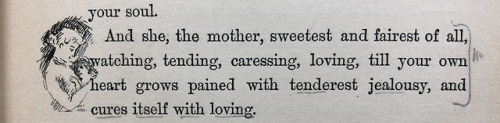

The text itself is divided into four “reveries” in which a bachelor contemplates boyhood, marriage, country life, travel, and even the phenomenon of dreaming itself. Chapters include “Smoke – signifying doubt,” “Blaze – signifying cheer,” and “Ashes – signifying desolation.”

We were fortunate enough to have recently acquired a fascinating copy of the 1886 New York edition of Reveries of a Bachelor. Our copy was originally purchased in 1887 by Clifford Julius King (1865-1910), an Ohio attorney who practiced in Ashtabula (as King did not marry until 1891, he was still a bachelor himself when he bought the book). King had more than just a passing interest in books, as he was a member of the Rowfant Club, an organization for bibliophiles founded in 1892 in Cleveland and still active today.

King is presumably responsible for several other characteristics that make this copy stand out. First is a signed letter by Mitchell, perhaps written to King, pasted into the volume along with two portraits of the author. The letter reads:

My dr. Sir –

I have yr favor of 2nd inst

to send you the autograph

you ask for: I am too old

a man to make engagements

far from home.Yrs vry truly,

Dond. G. MitchellEdgewood 4th Novr. 1891

Additionally, an artist known only by the initials B.K.C. has contributed numerous pen and ink wash illustrations to this copy, some of which bear an 1887 date. In total, there are seven full-page images, 17 head and tail vignettes, and 73 marginal illustrations. These drawings really bring Mitchell’s text alive, and the marginal vignettes especially heighten the dream-like aspect of the book, depicting subjects such as a hand lighting a lamp, a foot entering a shoe, or the floating head of a woman.

Though it is not explicitly stated, it is likely that Clifford Julius King, due to his bibliophilic interests, was responsible for embellishing this copy by collecting the Mitchell paraphernalia and assembling it together with the illustrated text. The result is a copy of Reveries of a Bachelor that is truly unique — and truly special!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b12953883~S39a

Post link

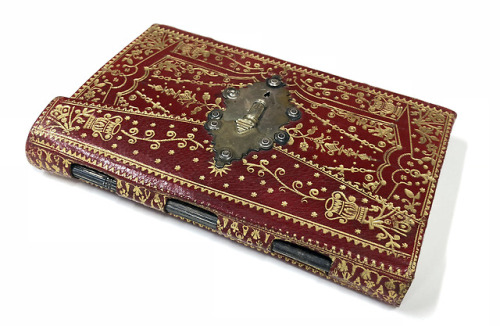

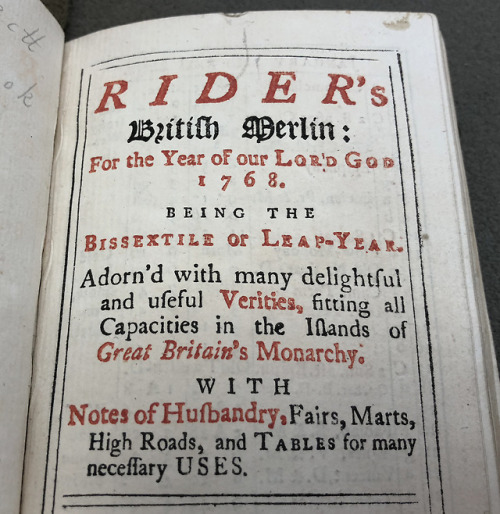

Unlocking a 250-Year-Old Almanac

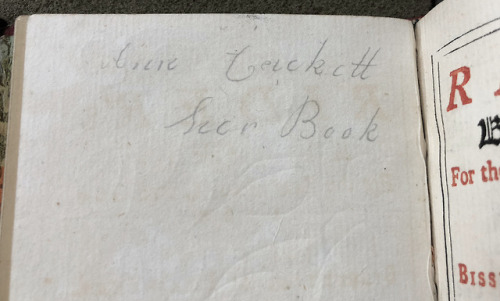

Special Collections has recently acquired an intriguing copy of Rider’s British Merlin, an almanac published in London in 1768 — 250 years ago this year!

Rider’s almanac first appeared in 1656, “compiled for the benefit of his country” by one “Schardanus Rider,” believed to be an anagram of the name of physician and astrologer Richard Saunders (1613-1675). The almanac continued to be published for many years after his death.

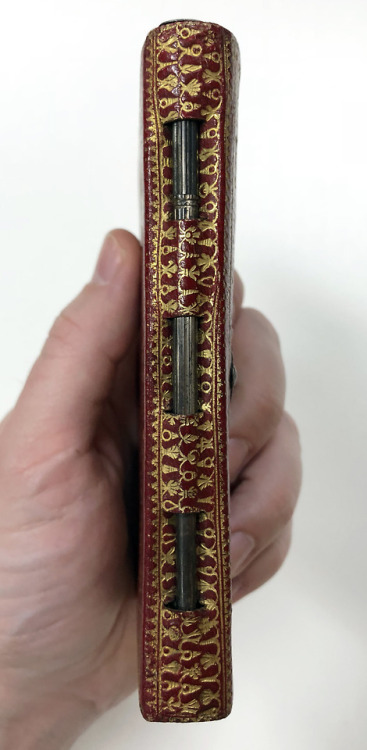

A number of special features make our copy uniquely interesting, such as its elaborate red morocco binding. Perhaps most fascinating is the metal lock, which is actually even more complex than it might appear at first glance. In spite of the provided key, it seems that the only way to truly open the lock is through a secret mechanism — by gently sliding one of the rivets connecting the lock to the cover, the inner latch shifts, and the flap can be opened.

A convenient slot is incorporated into the flap to store a metal stylus, which is (happily) still present. This was used for taking notes on a pair of waxed sheets bound in at the front of the volume, which effectively acted as erasable writing tablets. In much the same way that the ancient Romans used wax-filled wooden frames for temporary note-taking, the pages in this almanac could be incised with the stylus and then erased at the appropriate time. An owner of this volume — perhaps Ann Cackett (?), who wrote her name on one of the flyleaves — has used the stylus many times, leaving incisions behind in the form of repeated circles and other rudimentary markings.

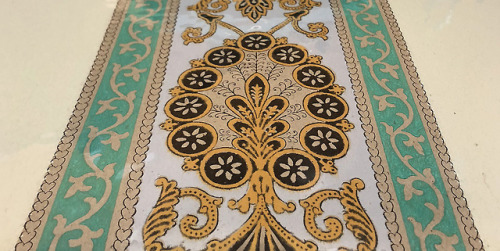

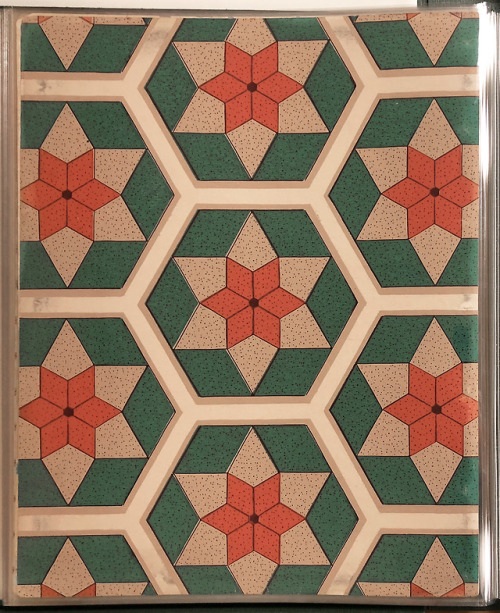

Inside each cover is a little fold-out pocket for the storage of important documents, though sadly they arrived at our library empty. These pockets are partially formed by the end-papers, which are made from beautiful multicolored Dutch gilt paper (actually originating in Germany). Our papers bear a portion of the name of their maker: “Johan Wilhelm.”

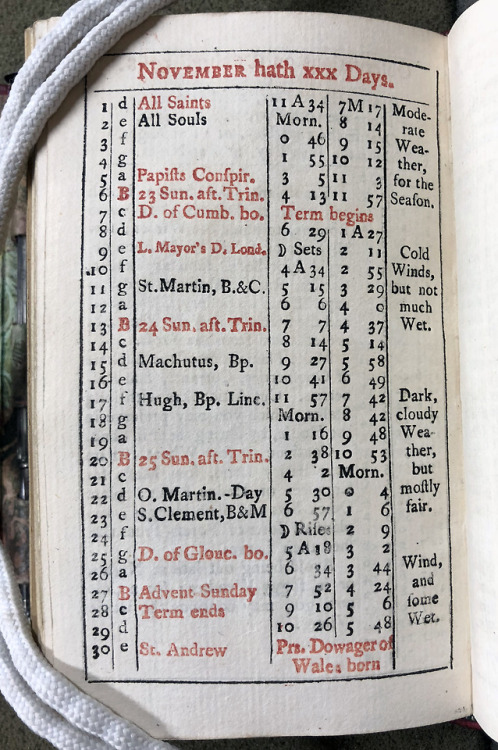

It’s easy to concentrate on this almanac’s bells and whistles, but it is also rewarding to look at its contents. It opens with a handsome calendar, printed in red and black, that incorporates religious, astronomical, meteorological, and agricultural observations. Other sections include a list of the year’s moveable feasts (holy days that occur on different days each year), a calendar of eclipses, a zodiac man (a diagram of the relationships of the planets to various parts of the human body), a table of the monarchs and the dates of their reigns, a description of the country’s major roads with the distances between towns, and an extensive list of the fairs regularly held in England and Wales.

Several pages are filled with the reckoning of the years since major events – 4061 since Noah’s Flood, 315 since “printing first used in England” (this is about 20 years earlier than the date generally accepted today), 188 since “a blazing star in May” was observed, and five since “a general peace.” Finally, there is a tipped-in sheet documenting “An account of the holydays” for 1768. (This is unrecorded in the English short title catalogue.)

We are excited to add this unique almanac to our collection, and look forward to welcoming you into our reading room to see it in person!

Post link

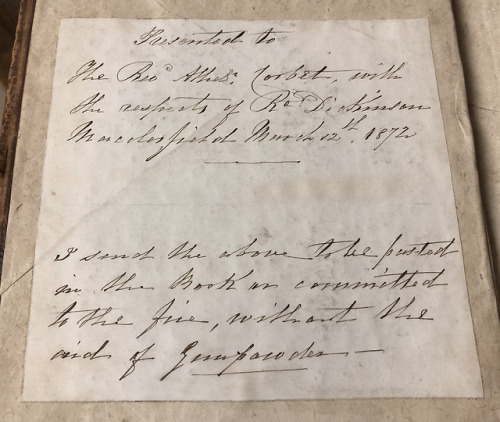

Remember, remember, the fifth of November!

Tonight is Guy Fawkes Night, an annual remembrance in the United Kingdom of the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in which Robert Catesby, Guy Fawkes, and other Catholic revolutionaries attempted to assassinate the Protestant King James I by blowing up the House of Lords during the opening of Parliament.

This1606 account of the trial of Henry Garnet, one of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators, bears an interesting and relevant presentation inscription pasted onto the front endpaper:

Presented to

the Revd. Athels[ta]n Corbet, with

the respects of Revd. Dickinson

Macclesfield March 12th, 1872I send the above to be pasted

in the book or committed

to the fire, without the

aid of gunpowder

Obviously (and thankfully, for provenance purposes), this presentation note was spared the fire!

~Andrew

Post link

“It had the power of a thousand scorpions…”

- Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Sometimes books can kill.

Take this book, for example. Shadows from the Walls of Death is a 19th century collection of arsenic-laced wallpaper samples. Each of the striking specimens was colored with an arsenic-based pigment, and touching the pages with your bare hands could make you seriously ill, or worse.

Hopefully by now you’ve read our 2015 Tumblr post onShadowsor Atlas Obscura’s recent article on the poison book, but here’s some background in case you haven’t:

Copper arsenite was not an uncommon ingredient in paints and pigments throughout the 19th century, most often used to produce the vibrant greens known as Paris Green or Scheele’s Green. While people of the time knew that arsenic was dangerous if ingested, they saw little risk in using the poisonous element to color wallpaper – after all, who’s going around licking their walls?

But then in the 1870s, Robert Kedzie – a doctor, MSU chemistry professor, and public health advocate – showed that fine particles of this arsenical wallpaper could shed when touched, or worse: they could “dust off” into the air, causing people to fall ill and die by just existing in a house coated with the stuff.

Kedzie put together 100 books of the deadly wallpaper samples and sent them to libraries throughout Michigan, to educate the public about the potential dangers of this common household item.

Only a handful of copies of this toxic book remain – most were destroyed long ago due to their poison pages. Of the surviving volumes, MSU’s copy is believed to be the most extensive, or most complete – containing over 130 individual wallpaper samples.

Most of the wallpaper specimens feature the color green, but not all – the same arsenical dye that went into the infamous Paris Green or Scheele’s Green was often mixed to form other colors, and many of our samples boast beautiful deep blues and golden yellows.

Most of the images here have never been seen before. Some day it’s possible that we will digitize our copy of Shadows, as the National Library of Medicine has done with theirs, but that poses some significant challenges.

In the meantime, every page in our copy has been painstakingly encapsulated in archival sleeves – meaning that patrons can safely view the book up close without fear of succumbing to arsenic poisoning. But if you can’t make it out to see the volume in person, I hope you will enjoy these new photos of this intriguingly beautiful book.

Beautiful, but deadly.

~Andrew

Post link

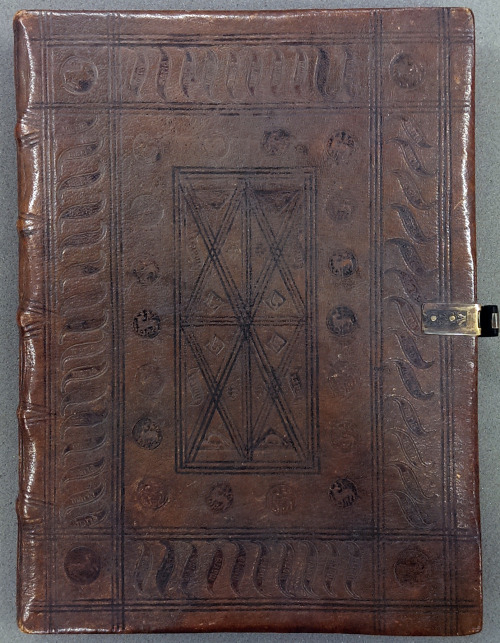

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

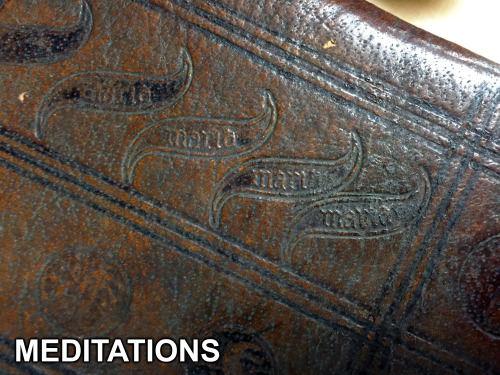

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

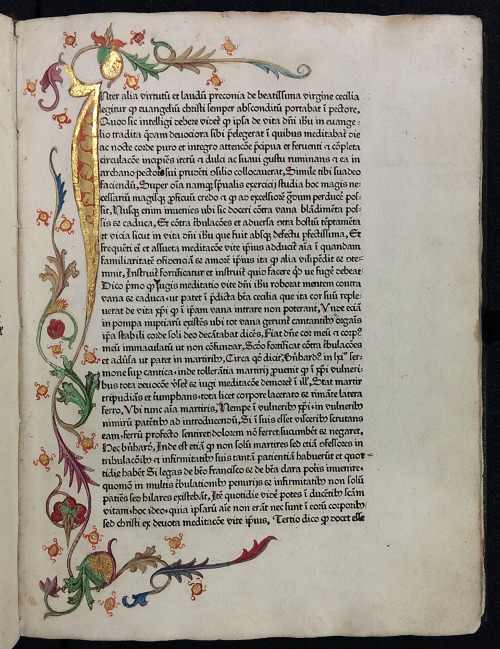

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

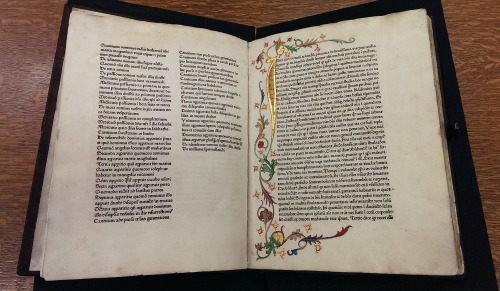

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link