#epigraphy

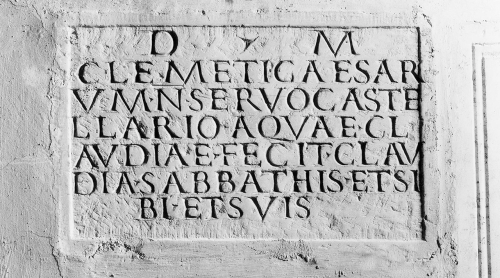

Marble slab from the family tomb of a castellarius

The inscription reads:

D(is) M(anibus) / Cleme(n)ti Caesar/um n(ostrorum) / servo caste/llario aquae Cl/audiae fecit Clau/dia Sabbathis et si/bi et suis

The deceased, Clemens, controlled the distribution tanks (castella) of the Aqua Claudia (initiated by Caligula in 38 and completed by Claudius in 52), mentioned in the epigraph of the arches (now Porta Maggiore) incorporated in the Aurelian Walls (the final part of a 69 km path fed by springs from the upper valley of the River Aniene). The massive water system that served the capital of the Empire, described in a monograph by Frontinus, alone offers an indication of the magnificence of the city, divided into 14 regions and filled with fountains and thermal baths. Clemens was buried by his wife who bears, alongside a name of Semitic origin (Sabbathis), the same family name as Claudius. Perhaps the deceased (referred to generically as “slave of our Caesars”) belonged to this emperor and others who succeeded him rather than to the two co-reigning emperors: Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (161-169 A.D.), M. Aurelio and Comodo (177-180 A.D.) or Septimius Severus and Caracalla (198-209 A.D.).

From Rome, unknown burial monument

Second half of the first – late second century A.D.

© Roma, Musei Vaticani, Galleria Lapidaria

Post link

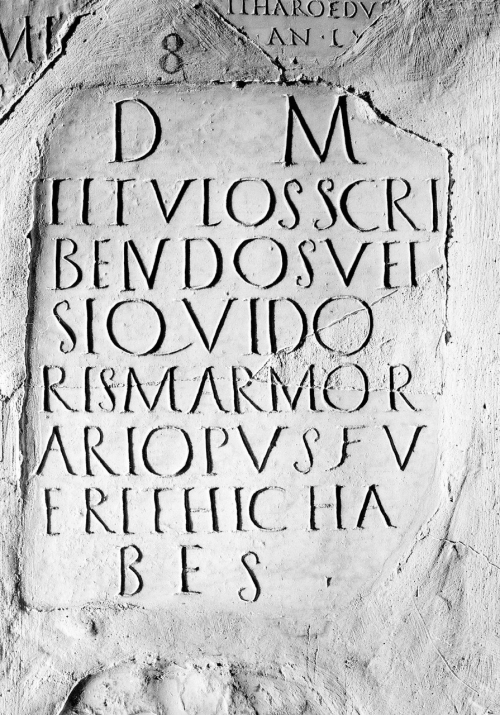

“Need an inscription carving or anything else in marble? Here you have it”

Engraved on a marble slab, the text indicated to locals and passers-by the presence of a marble worker’sworkshop, where marble was carved and epigraphs were also engraved, as the expression scribere titulus attests:

D(is) M(anibus) / titulos scri/bendos vel / si quid ope/ris marmor/ari(i) opus fu/erit hic ha/bes.

In a sign from Palermo we instead read: “Here inscriptions can be ordered and carved” (tituli heic ordinantur et sculpuntur), while another text, mutilated, possibly commemorates a Vitalis scriptor titulorum, “engraver of epigraphs”. The poor quality of the item, the messy style of the text and the mediocre engraving of the characters suggest a small shop, frequented by customers with little money and few pretensions. We do not know the location, but it may originate from the area of Campus Martius which is known to have had a high concentration of marble workshops.

II-III century A.D., from Rome

© Roma, Musei Vaticani, Galleria Lapidaria

Post link

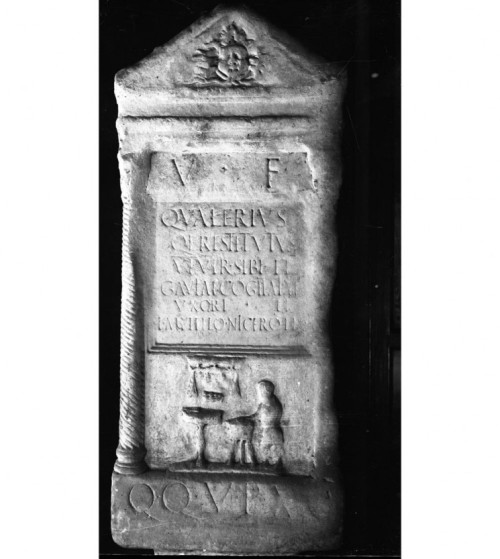

Funerary stele, made of limestone, of the freedman and sevir Q. Valerius Restitutus. Still alive, he erected the funeral monument for himself, for his wife and for Lucius Metellus Niceros. The structure has two columns on the sides with corinthian capitals, a pediment with Gorgon’s face, and perhaps two corner acroteria in the shape of lions. There is a bass-relief in the lower part with an artisan, maybe an aurifex brattiarius, a jewellery maker, or a lanius, butcher. The second hypothesis is supported by the discovery of a boundary stone with the figure of a bull on the pediment and an inscription which indicates the same dimensions of the funerary area (20 x 20 roman feet).

The text reads:

V(ivus) f(ecit) / Q(uintus) Valerius / Q(uinti) l(ibertus) Restitutus / VIvir sibi et / Gaviae Cogitatae / uxori et / L(ucio) Metello Niceroti / q(uo)q(uo)v(ersus) p(edes) XX

First half of 1st century AD

@ Archaeological Museum of Bologna

Post link

Marble funerary Inscription of Caecilius Hilarius, physician to the famous Caecilia Metella. Her circular tomb is still seen as a large monument on the Appian Way south of Rome.

The inscription reads:

Q(uintus) Caecilius Caeciliae / Crassi〈uxoris〉 l(ibertus) Hilarus, medicus,

/ Caecilia duarum / Scriboniarum l(iberta) / Eleutheris, / ex partem dimidiae sibi êt suis.

meaning: “Quintus Caecilius Hilarus, a doctor, / Freedman of Caecilia, wife of Crassus. / Caecilia Eleutheris, freedwoman of / two Scriboniae. With the share of a half. / For himself (themselves?) and their (family).”

The doctor’s praenomen Quintus was taken from the name of Caecilia Metella’s father. Caecilia Eleutheris was Hilarus’ wife. She was the freedwoman of the two “Scriboniae,” one of whom was the first wife of Augustus (40-39 BC) and mother of his only child, Julia. The other sister was married to the son of Pompey the Great, Sextus Pompeius, who was defeated by Augustus/Octavian in 36 BC.

In the second line, the inscriber ran out of space and put the final “us” of “medicus” in small letters.

27 BC / 14 AD.

Found in Rome on the via Salaria in the so-called “Monumentum Caeciliorum“.

© Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Post link

Marble funerary altar, carved in high relief with the figure of the deceased, named in the accompanying, elegantly carved Latin inscription as Anthus. The altar was set up by his father, L(ucius) Iulius Gamus. Although Anthus’ age is not given, he clearly died while still a child, since he is referred to as “(his) sweetest son,” and a personal touch is given to the relief by showing Anthus with his pet dog.

The inscription reads: Diis Manib(us) / Anthi / L(ucius) Iulius Gamus pater fil(io) dulcissim(o), meaning “To the Spirits of the Departed. Lucius Iulius Gamus, father, to Anthus, (his) sweetest son”.

1st half of 1st century A.D.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Post link

Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp

Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)

meaning

“(Brick Stamp) of the Two Lesagori”.

The “two Lesagori” were probably brothers. The name of one of them, Lucius Lesagius Tritogenes, is known from another stamp.

2nd century AD

© Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Post link

Marble lid of a cinerary chest, fashioned to look like the roof of a barrel-vaulted building with acroteria at the corners in the form of theatrical masks and palmettes. The inscription on the front panel reads:

D(is) M(anibus) / Sex(ti) Flavi / Pancarpi / q(ui) vix(it) ann(os) LXVII

meaning “To the spirits of the dead, [of] Sextus Flavius Pancarpus, who lived 67 years.”

Despite the fact that the inscription mentions only a man, the lunettes at the sides show both male (globe and box of scrolls) and female (mirror and spindle) attributes, indicating that the chest also may have contained the remains of Pancarpus’ wife.

Late 1st century AD

© Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

Post link

Lead ingot with inscribed stamp of the manufacturer. The ingot was found, with other one thousand pieces, in a Roman shipwreck located in 1989 in the stretch of sea between the coast of Sinis and the island of Mal di Ventre, in Sardinia.

This load of lead ingots is the biggest one ever documented in the ancient world. It was placed in the center of the ship and consisted of about one thousand ingots, all trapezoidal in shape, weighing about 33 kg each. Many of the ingots were still lined up and stacked in their original positions because apparently, the vessel sank slowly and almost vertically without tipping the load. The ingots each have an epigraphic cartouche (mold marks) bearing the name of the manufacturers, such as:

Soc(ietatis) M(arci) C(ai) Pontilienorum M(arci) f(iliorum)

indicating the“Company [owned] by Marcus and Caius Pontilienus, sons of Marcus”.

In collaboration with the National Institute of Nuclear Physics and the Institute of Isotope Geochronology and Geochemistry, CNR of Pisa, numerous analyses were undertaken on the ingots. The results of these analyses have been published and presented at various exhibitions in Europe and America. The analyses have demonstrated the exceptional purity of the metal in the ingots, which came from the Sierra mining region of Cartagena, Spain, which is also probably where the ship sailed from during the first century BC. The final destination of the ship is not known.

1st century BC

© Museo Civico Giovanni Marongiu, Cabras (Italy) [x]

Post link

Marble cinerary chest with lid. Above the inscription is a scene in which the deceased, standing on a pedestal, is making an offering to a female figure, perhaps Tellus (mother earth), who reclines on a couch bedecked with flowers. They are attended by two young servants, holding food and wine. The chest is in the form of a pedimental building, with flaming torches taking the place of columns at the corners.

The latin inscription reads:

Dis Manibus. / M(arcus) Domiti/us Primigenius fecit sibi / et suis, libertis libertabusq(ue) / posterisque eorum.

It translates:

“To the spirits of the dead. M. Domitius Primigenius made [this] for himself, his freedmen and freedwomen, and their descendants.”

A.D. 90–110 ca., from Rome

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Post link

This relief originally formed part of the funerary monument of Lucius Antistius Sarculo, a free-born Roman, master of the Alban college of Salian priests, and his wife and freedwoman Antistia Plutia. The relief was dedicated by two freedmen, Rufus and Anthus, in recognition of their patron’s good deeds. The inscription reads:

L(ucius) Antistius Cn(aei) f(ilius) Hor(atia) Sarculo, / Salius Albanus ìdem mag(ister) Saliorum.

Antistia / L(uci) l(iberta) Plutia.

Rufus, l(ibertus), Anthus, l(ibertus), imagines de suo fecerunt patrono et patronae pro meritis eorum.

And translates: “Lucius Antistius Sarculo, son of Gnaeus, member of the Horatia tribe, priest of the Alban Salian Order, as well as Master of the priests.

Antistia Plutia, freedwoman of Lucius.

The freedman Rufus (and) the freedman Anthus had these portraits made out of their own funds for their patron and patroness in recognition of their worthy deeds.”

The lined eyes, the slightly hollowed cheeks and prominent earsof Antistius, and the thin-lipped, severe countenance of his wife are typical of the realistic style characteristic of the period. The couple’s hairstyles indicate a date towards the end of the first century BC. During the Republic, large numbers of slaves were brought to Rome and Italy following the conquests of territories such as Spain and Greece. Augustus gave freedmen and women many rights and privileges, including (happily for Antistius) the right to marry Roman citizens. Antistia’s rise, from humble slave to wife of a Salian, underlines the extent of Augustus’ social revolution. The roads around Rome and other cities in the empire were lined with monuments from which similar reliefs of freedmen and their families looked out, proudly proclaiming their full membership of Roman society.

50 BC - 1 BC, from Rome

© Trustees of the British Museum, London

Post link

- Escorting teachers during educational visits of schools and institutions of primary, secondary and tertiary education and of military schools.

- Holders of a free pass

- Holders of a solidarity card

- Holders of a valid unemployment card.

- Journalists upon presentation of their journalist identity card

- Members of Societies and Associations of Friends of Museums and Archaeological Sites, upon presentation of their certified membership card.

- Members of the Chamber of Fine Arts of Greece and equivalent Chambers of member-states of the EU, upon presentation of their membership card

- Members of the ICOM-ICOMOS, upon presentation of their membership card

- Official guests of the Greek State, after approval from the General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage.

- Parents of families with three children and their children up to the age of 23 or 24 if they are students and regardless of age if they have disability, upon presentation of a family status certificate issued by the Municipality

- Parents of multi-child families and their children up to the age of 23, up to the age of 25 if they are doing their military service or studying and regardless of age if they have disabilities, upon presentation of a certified multi-child pass from the Supreme Confederation of multi-child parents of Greece (ASPE).

- Persons with disabilities (67 % or over) and one escort, upon presentation of the certification of disability issued by the Ministry of Health or a medical certification from a public hospital, where the disability and the percentage of disability are clearly stated

- Single parent families with minors, upon presentation of a family status certificate issued by the Municipality. In the case of divorsed parents, only the parent holding custody of the children

- Students of University - Higher Education Institutes, Technological Educational Institutes, Military Schools or equivalent Schools of EU member states, as well as Schools of Guides, upon presentation of their student identity card

- The employees of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and the Archaeological Receipts Fund, upon presentation of their service ID card.

- The police officers of the Department of Antiquity Smuggling of the Directorate of Security

- Tourist guides upon presentation of their professional ID card.

- Young people, up to the age of 18, upon presentation of their Identity Card or passport for age confirmation.

(x)

THE EINSIEDELN ITINERARY

The library of the Benedictine monastery of Einsiedeln contains a miscellany (Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek Codex 326) compiled over the 9th and 10th centuries at unknown German monastery. The two most important texts, the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae and the Itinerarium Urbis Romae, were composed in Rome in the early 9th century. The author is known today as the Anonymous of Einsiedeln because the only surviving copy of his work is located in the Stiftbibliothek; the author had no connection to the Swiss monastery. The Einsiedeln texts were redacted by a northern scribe in a clearly-legible Caroline miniscule, from either a German or Italian manuscript source.

TheItinerarium (fols. 79v-89r) is a topographical guide to the principal monuments of the city. Composed for pilgrims visiting the city, the text consists of a series of walks across the city beginning and ending at different city gates. Both pagan and Christian monuments are indicated. For most monuments, the text is only list of names with no descriptions. Many of those casually mentioned names—Theatrum Pompei, Septizonium, Thermae Traiani, Capitolium—however, grip the modern reader’s attention, reminding him/her of how many major monuments of which no trace remains today, were still standing and correctly identified in the Carolingian period.

The itinareries are accompanied by the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae (67r-79v). This collection records epigraphic inscriptions seen on bridges, temples, arches, baths, basilicae, column and statue bases, and so on. As the majority of those monuments no longer survive, the Einsiedeln transcriptions are of vital importance to any understanding of ancient Roman topography, imperial patronage, and architectural and urban history. In the few cases where the source of a redaction by the Anonymous still exists, his transcritions have proved to be accurate.

Given its usefulness, the text must have been popular among foreign visitors to Rome. The Einsiedeln manuscript however, is the only known copy of the ItinerariumandInscriptiones.Although the volume had entered the library’s collection in the 17th century, those texts were “discovered” and correctly identified only in the 19th century.

![Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)meaning “(Brick Stamp) of Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)meaning “(Brick Stamp) of](https://64.media.tumblr.com/4d46411311596b8212ae63ae5abdeaac/40761ccac4a4a369-55/s500x750/c99e968e9af10b2290a0aea7776bcee296eeace3.jpg)