#roman history

say what you will about the ancient romans and all of the terrible things they did in the name of empire, but they understood how much jewelry shaped like snakes slaps and you really have to give them credit for that

Like everything allegedly good about the Roman Empire, awesome snake jewelry is something they “acquired” from other cultures and claimed as their own.

So no, you don’t have to give them credit for that.

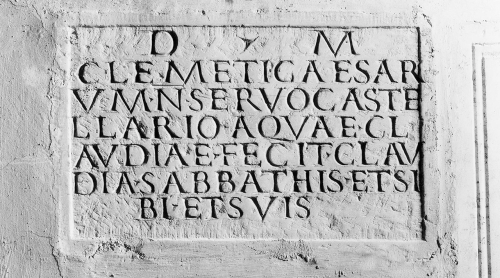

Marble slab from the family tomb of a castellarius

The inscription reads:

D(is) M(anibus) / Cleme(n)ti Caesar/um n(ostrorum) / servo caste/llario aquae Cl/audiae fecit Clau/dia Sabbathis et si/bi et suis

The deceased, Clemens, controlled the distribution tanks (castella) of the Aqua Claudia (initiated by Caligula in 38 and completed by Claudius in 52), mentioned in the epigraph of the arches (now Porta Maggiore) incorporated in the Aurelian Walls (the final part of a 69 km path fed by springs from the upper valley of the River Aniene). The massive water system that served the capital of the Empire, described in a monograph by Frontinus, alone offers an indication of the magnificence of the city, divided into 14 regions and filled with fountains and thermal baths. Clemens was buried by his wife who bears, alongside a name of Semitic origin (Sabbathis), the same family name as Claudius. Perhaps the deceased (referred to generically as “slave of our Caesars”) belonged to this emperor and others who succeeded him rather than to the two co-reigning emperors: Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (161-169 A.D.), M. Aurelio and Comodo (177-180 A.D.) or Septimius Severus and Caracalla (198-209 A.D.).

From Rome, unknown burial monument

Second half of the first – late second century A.D.

© Roma, Musei Vaticani, Galleria Lapidaria

Post link

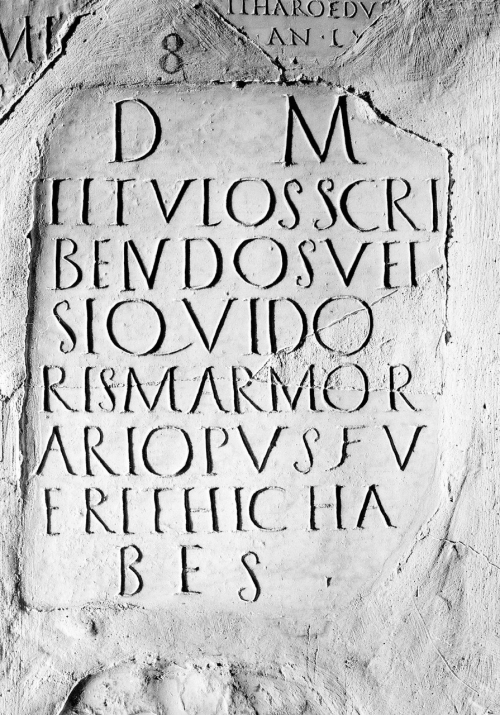

“Need an inscription carving or anything else in marble? Here you have it”

Engraved on a marble slab, the text indicated to locals and passers-by the presence of a marble worker’sworkshop, where marble was carved and epigraphs were also engraved, as the expression scribere titulus attests:

D(is) M(anibus) / titulos scri/bendos vel / si quid ope/ris marmor/ari(i) opus fu/erit hic ha/bes.

In a sign from Palermo we instead read: “Here inscriptions can be ordered and carved” (tituli heic ordinantur et sculpuntur), while another text, mutilated, possibly commemorates a Vitalis scriptor titulorum, “engraver of epigraphs”. The poor quality of the item, the messy style of the text and the mediocre engraving of the characters suggest a small shop, frequented by customers with little money and few pretensions. We do not know the location, but it may originate from the area of Campus Martius which is known to have had a high concentration of marble workshops.

II-III century A.D., from Rome

© Roma, Musei Vaticani, Galleria Lapidaria

Post link

The so-called Psyche di Capua (actually a Venus), is a statue found in 1726 in the Campano amphitheater in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, where it decorated the front porch of the summa cavea together with other sculptures.

Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Photo: Luigi Spina

Post link

Silver skillet, with a highly decorated handle and some gilding. The bowl is deep, with slightly incurving walls forming a constriction in the line of the profile below the small everted rim.

The general theme of the decoration is the traditional one of acanthus scrolls and flowers, with some elements picked out by gilding. The central area of the handle carries the inscription MATR FAB / DVBIT in bold, neat lettering. The outlines of the letters are filled with a roughened surface to provide a key for the heavy gilding, perhaps more accurately termed ‘gold inlay’, which survives on the V, B and T of 'DVBIT’.

The skillet, part of the Backworth Hoard, bears a votive inscription dedicated to the Mother-Goddesses by a Fab(ius) Dubit(atus?).

The history of this hoard is obscure. We know that it was found around 1811, but not where it was found. The hoard was said to have included about 280 coins, but all but one of these, and probably other objects, were dispersed before The British Museum was able to acquire what was left of the treasure in 1850. The surviving coin is a denarius of Antoninus Pius (reigned AD 138-161) issued in AD 139.

The treasure was probably a votive deposit at a shrine of the Mother-goddesses near the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall.

1st - 2nd century AD

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Post link

Gold finger-ring with slight flattening of the shoulders. The hoop is slightly bevelled in cross-section. The almost circular gem-setting is empty, and encircled at the rim with applied beaded wire, which is heavily worn. The floor of the setting has been scraped flat, but not polished, and bears a three-line inscription: MATR/VM CO/COAE. Although the exact translation is uncertain, this is certainly a votive gift to the Mother Goddesses. The inscription is probably secondary, engraved after a gemstone setting had been lost.

Found in Backworth (England), part of the Backworth Hoard.

The history of this hoard is obscure. We know that it was found around 1811, but not where it was found. The hoard was said to have included about 280 coins, but all but one of these, and probably other objects, were dispersed before The British Museum was able to acquire what was left of the treasure in 1850. The surviving coin is a denarius of Antoninus Pius (reigned AD 138-161) issued in AD 139.

The treasure was probably a votive deposit at a shrine of the Mother-goddesses near the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall.

1st - 2nd century AD

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Post link

Ercole Farnese

Roman marble copy of a bronze original by Lysippos (4th c. BC)

3rd century AD

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

© Ph. Luigi Spina

Post link

Afrodite Sosandra

Roman marble copy of an original attributed to the Greek sculptor Calamis (ca. 460 BC).

2nd century AD

National Archeological Museum, Naples

© Ph. Luigi Spina

Post link

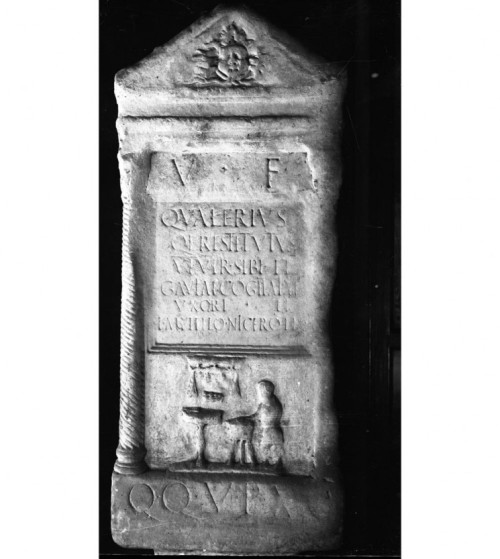

Funerary stele, made of limestone, of the freedman and sevir Q. Valerius Restitutus. Still alive, he erected the funeral monument for himself, for his wife and for Lucius Metellus Niceros. The structure has two columns on the sides with corinthian capitals, a pediment with Gorgon’s face, and perhaps two corner acroteria in the shape of lions. There is a bass-relief in the lower part with an artisan, maybe an aurifex brattiarius, a jewellery maker, or a lanius, butcher. The second hypothesis is supported by the discovery of a boundary stone with the figure of a bull on the pediment and an inscription which indicates the same dimensions of the funerary area (20 x 20 roman feet).

The text reads:

V(ivus) f(ecit) / Q(uintus) Valerius / Q(uinti) l(ibertus) Restitutus / VIvir sibi et / Gaviae Cogitatae / uxori et / L(ucio) Metello Niceroti / q(uo)q(uo)v(ersus) p(edes) XX

First half of 1st century AD

@ Archaeological Museum of Bologna

Post link

Sword-belt decoration (phalera), worn on the breast as an ornament by soldiers, especially as a military decoration, or used to adorn the harness of horses.

The inscription reads LG X FR FEL, abbreviated form for the name of the Tenth Legion “Fretensis Felix”.

Early 3rd century AD

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Post link

Marble funerary Inscription of Caecilius Hilarius, physician to the famous Caecilia Metella. Her circular tomb is still seen as a large monument on the Appian Way south of Rome.

The inscription reads:

Q(uintus) Caecilius Caeciliae / Crassi〈uxoris〉 l(ibertus) Hilarus, medicus,

/ Caecilia duarum / Scriboniarum l(iberta) / Eleutheris, / ex partem dimidiae sibi êt suis.

meaning: “Quintus Caecilius Hilarus, a doctor, / Freedman of Caecilia, wife of Crassus. / Caecilia Eleutheris, freedwoman of / two Scriboniae. With the share of a half. / For himself (themselves?) and their (family).”

The doctor’s praenomen Quintus was taken from the name of Caecilia Metella’s father. Caecilia Eleutheris was Hilarus’ wife. She was the freedwoman of the two “Scriboniae,” one of whom was the first wife of Augustus (40-39 BC) and mother of his only child, Julia. The other sister was married to the son of Pompey the Great, Sextus Pompeius, who was defeated by Augustus/Octavian in 36 BC.

In the second line, the inscriber ran out of space and put the final “us” of “medicus” in small letters.

27 BC / 14 AD.

Found in Rome on the via Salaria in the so-called “Monumentum Caeciliorum“.

© Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Post link

Marble funerary altar, carved in high relief with the figure of the deceased, named in the accompanying, elegantly carved Latin inscription as Anthus. The altar was set up by his father, L(ucius) Iulius Gamus. Although Anthus’ age is not given, he clearly died while still a child, since he is referred to as “(his) sweetest son,” and a personal touch is given to the relief by showing Anthus with his pet dog.

The inscription reads: Diis Manib(us) / Anthi / L(ucius) Iulius Gamus pater fil(io) dulcissim(o), meaning “To the Spirits of the Departed. Lucius Iulius Gamus, father, to Anthus, (his) sweetest son”.

1st half of 1st century A.D.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Post link

Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp

Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)

meaning

“(Brick Stamp) of the Two Lesagori”.

The “two Lesagori” were probably brothers. The name of one of them, Lucius Lesagius Tritogenes, is known from another stamp.

2nd century AD

© Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Post link

Marble lid of a cinerary chest, fashioned to look like the roof of a barrel-vaulted building with acroteria at the corners in the form of theatrical masks and palmettes. The inscription on the front panel reads:

D(is) M(anibus) / Sex(ti) Flavi / Pancarpi / q(ui) vix(it) ann(os) LXVII

meaning “To the spirits of the dead, [of] Sextus Flavius Pancarpus, who lived 67 years.”

Despite the fact that the inscription mentions only a man, the lunettes at the sides show both male (globe and box of scrolls) and female (mirror and spindle) attributes, indicating that the chest also may have contained the remains of Pancarpus’ wife.

Late 1st century AD

© Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

Post link

Lead ingot with inscribed stamp of the manufacturer. The ingot was found, with other one thousand pieces, in a Roman shipwreck located in 1989 in the stretch of sea between the coast of Sinis and the island of Mal di Ventre, in Sardinia.

This load of lead ingots is the biggest one ever documented in the ancient world. It was placed in the center of the ship and consisted of about one thousand ingots, all trapezoidal in shape, weighing about 33 kg each. Many of the ingots were still lined up and stacked in their original positions because apparently, the vessel sank slowly and almost vertically without tipping the load. The ingots each have an epigraphic cartouche (mold marks) bearing the name of the manufacturers, such as:

Soc(ietatis) M(arci) C(ai) Pontilienorum M(arci) f(iliorum)

indicating the“Company [owned] by Marcus and Caius Pontilienus, sons of Marcus”.

In collaboration with the National Institute of Nuclear Physics and the Institute of Isotope Geochronology and Geochemistry, CNR of Pisa, numerous analyses were undertaken on the ingots. The results of these analyses have been published and presented at various exhibitions in Europe and America. The analyses have demonstrated the exceptional purity of the metal in the ingots, which came from the Sierra mining region of Cartagena, Spain, which is also probably where the ship sailed from during the first century BC. The final destination of the ship is not known.

1st century BC

© Museo Civico Giovanni Marongiu, Cabras (Italy) [x]

Post link

Marble cinerary chest with lid. Above the inscription is a scene in which the deceased, standing on a pedestal, is making an offering to a female figure, perhaps Tellus (mother earth), who reclines on a couch bedecked with flowers. They are attended by two young servants, holding food and wine. The chest is in the form of a pedimental building, with flaming torches taking the place of columns at the corners.

The latin inscription reads:

Dis Manibus. / M(arcus) Domiti/us Primigenius fecit sibi / et suis, libertis libertabusq(ue) / posterisque eorum.

It translates:

“To the spirits of the dead. M. Domitius Primigenius made [this] for himself, his freedmen and freedwomen, and their descendants.”

A.D. 90–110 ca., from Rome

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Post link

This relief originally formed part of the funerary monument of Lucius Antistius Sarculo, a free-born Roman, master of the Alban college of Salian priests, and his wife and freedwoman Antistia Plutia. The relief was dedicated by two freedmen, Rufus and Anthus, in recognition of their patron’s good deeds. The inscription reads:

L(ucius) Antistius Cn(aei) f(ilius) Hor(atia) Sarculo, / Salius Albanus ìdem mag(ister) Saliorum.

Antistia / L(uci) l(iberta) Plutia.

Rufus, l(ibertus), Anthus, l(ibertus), imagines de suo fecerunt patrono et patronae pro meritis eorum.

And translates: “Lucius Antistius Sarculo, son of Gnaeus, member of the Horatia tribe, priest of the Alban Salian Order, as well as Master of the priests.

Antistia Plutia, freedwoman of Lucius.

The freedman Rufus (and) the freedman Anthus had these portraits made out of their own funds for their patron and patroness in recognition of their worthy deeds.”

The lined eyes, the slightly hollowed cheeks and prominent earsof Antistius, and the thin-lipped, severe countenance of his wife are typical of the realistic style characteristic of the period. The couple’s hairstyles indicate a date towards the end of the first century BC. During the Republic, large numbers of slaves were brought to Rome and Italy following the conquests of territories such as Spain and Greece. Augustus gave freedmen and women many rights and privileges, including (happily for Antistius) the right to marry Roman citizens. Antistia’s rise, from humble slave to wife of a Salian, underlines the extent of Augustus’ social revolution. The roads around Rome and other cities in the empire were lined with monuments from which similar reliefs of freedmen and their families looked out, proudly proclaiming their full membership of Roman society.

50 BC - 1 BC, from Rome

© Trustees of the British Museum, London

Post link

Sixth-Century A.D. Mosaic Unearthed in Italy

A section of mosaic flooring from the 5th century palace of Ostrogoth king Theodoric has been discovered in Verona. The mosaic was found during installation of new gas pipes in the Montorio hamlet less than four miles from Verona’s historic town center.

Remains of an enormous country villa more than five acres in surface area have been turning up in Montorio since the 19th century. While there is no direct evidence that it was one Theodoric’s many palaces, the sheer size and scale strongly suggests it was a royal estate. If it wasn’t Theodoric’s palace, it must have belonged to someone of enormous wealth who was very close to him.

Theodoric was not technically a Roman emperor. He was three different varieties of king, though, starting in 475 A.D. as King of the Ostrogoths, then adding King of Italy in 493 and of the Visigoths in 511. By the time of his death in 526, Theodoric reigned over most of what had been the Western Roman Empire. He spent his childhood as a noble hostage at the imperial court in Constantinople and was educated there in the Eastern Roman tradition.

As ruler of a territory stretching from the Atlantic to the Danube, Theodoric embraced the ancient imperial trappings. He donned the purple, accepted the regalia of the Western Empire from Eastern Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus and allowed all Roman citizens in the kingdom to be governed by Roman judicial law. He instituted a vast program of reconstruction of Roman cities and infrastructure, restoring ancient aqueducts, baths, churches, the Aurelian walls of Rome and the defensive walls of a myriad other cities in Italy. He threw in a few new palaces for himself while he was at it, most famously in his capital of Ravenna, but also in other northern Italian cities like Verona.

The mosaic will remain in situ. It will be cleaned and documented in detail before being reburied. Some local residents have proposed covering it with plexiglass so the mosaic can still be seen, something that has been done already in Verona’s historic center, but this mosaic is in a terribly awkward position, trapped under networks of old pipes surrounded by homes, so it’s not a good candidate for display, unfortunately.

Post link

Marbled Monday

This Marbled Monday we’re sharing an oldie but a goodie— Romanae Historiae Compendium ab Interitu Gordiani Iunioris Vsque ad Iustinium by Julius Pomponius Laetus (1428-1498), humanist professor and founder of the Accademia Romana. Also known as Giulio Pomponio Leto, members of his academy took Greek or Latin names, so his original Italian name is unknown. The book is a text on Roman history from the death of Gordian the Younger to Justinus and was published in 1500 in Venice by Bernardinum Venetum de Vitalibus. The binding, however, is probably late nineteenth or early twentieth century.

The marbling on this half binding is a Serpentine pattern and is quite striking, with green, yellow, and a reddish-toned brown swirled together in sort of triangular or chevron-like pattern. I found this book while browsing the stacks for good marbling, and boy did I find some!

- Alice, Special Collections Department Manager

Post link

![Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)meaning “(Brick Stamp) of Fragment of roman brick with the orbicular stamp Duor(um) [Le]sagor(um)meaning “(Brick Stamp) of](https://64.media.tumblr.com/4d46411311596b8212ae63ae5abdeaac/40761ccac4a4a369-55/s500x750/c99e968e9af10b2290a0aea7776bcee296eeace3.jpg)