#god i love prehistoric marine invertebrates

Hallucigenia – Middle Cambrian (508 Ma)

It’s been too long since I featured something from the Burgess Shale. Last time, I featured Opabinia, along with an overview of the Cambrian Explosion and the history of our understanding of it. Today, we’re focusing on a little, inch-long invertebrate who lived alongside Opabinia, named Hallucigenia.

If you’ve ever seen a drawing or painting of a Cambrian landscape, it’s pretty likely you’ve seen Hallucigenia. It’s common as a backdrop animal in many portrayals of the Cambrian seas. Many of these tableaus are meant to evoke a feeling of unfamiliarity. They offer us a window to a much younger, alien earth. No fish swim overhead, and weird critters cover the seafloor. Hallucigenia is a perfect example of a weird critter. Then again, most of the fauna from the Cambrian period are. Most of the genera from the Cambrian have a story behind them, how we learned just how different they are from the things we know today, and this is no exception.

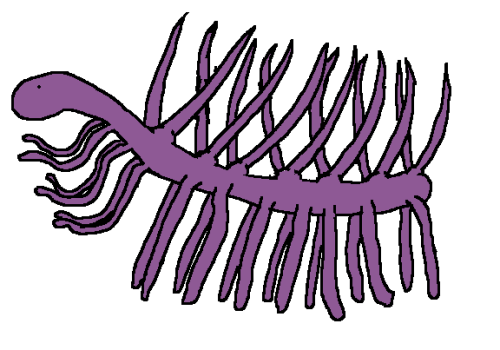

So, what is Hallucigenia? It’s weird, is what it is. This is normally the part where I, or any other amateur science communicator would reveal that it’s not actually as weird as it seems. The problem is, Hallucigenia really is that weird. It’s a soft-bodied worm with seven pairs of huge spikes on its back, and several tentacles underneath, perhaps used for walking. Also, it took us 50+ years to figure this out.

The Burgess Shale formation was discovered in 1909 by a man named Charles Doolittle Walcott. During his lifetime, he found and described hundreds of specimens from the Shale. However, Walcott was wrong about a lot of things. He misinterpreted several of the different fossils, including Hallucigenia. In fact, he didn’t even realize it was its own genus when he found it. For several decades, it was labeled as a specimen of an annelid worm called Canadia. It wasn’t until 1977 that paleontologist and personal idol of mine, Simon Conway Morris, recognized it as something very different. He reconstructed the animal more accurately and gave it its name, which, yeah, does come from the word ‘hallucinogen,’ because, I mean, look at this fucking thing.

Conway Morris didn’t get it quite right, though. For a while, we thought the spikes were on Hallucigenia’s underside, and that it used them to walk. In this interpretation, its tentacles would drift in the water and grab particles of food out of the air and carry them to its mouth. The accepted model has the spikes on its back, possibly as a defensive measure. We don’t know for certain that they were hard, since we haven’t found them preserved separately from the rest of the animal, like we do with other hard body parts.

This wasn’t the fault of poor fossil preservation—we have 109 specimens of Hallucigenia from the Burgess Shale, and they’re absolutely gorgeous. The problem is that this animal is so bizarre, so different from anything we have today. It’s hard to blame Walcott or Conway Morris for not being 100% correct about them right away.

So, now that we’ve studied these animals for so long, where does Hallucigenia fall on the tree of life? Good question. It’s a worm, but “worm” doesn’t really mean anything. All kinds of animals are worms, so what kind is this one? Scientists are torn, but two of the most popular hypotheses are that it’s either an early ancestor of velvet worms, or a distant cousin of what eventually became arthropods.

I could write an entire book about Hallucigenia and its cohorts in the Burgess Shale (in fact, one day, I want to), but I’m running late for some plans I have, so I’ll wrap it up here. Join me in a couple of days for… I don’t know. You ought to know I’m winging this by now.

Post link