#burgess shale

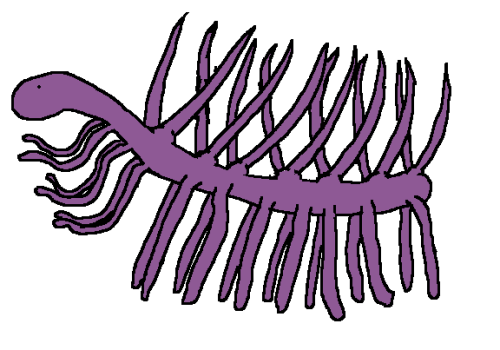

Louisella

Reconstruction by Marianne Collins

When: Cambrian (~505 million years ago)

Where: British Columbia, Canada

What: Louisella is a worm-type organism from the Burgess Shale formation in the Canadian Rockies of BC. This organism was about 12 inches (~30 centimeters) long, with a proboscis at its anterior end that could be inverted into the body or extruded. In the images above it is inverted into the body in the fossil specimen, but shown at its full extended length in the reconstruction. This structure was ringed by a series of spines with shorter and more robust spikes on the end of the proboscis. These structures would rub past one another as the animal extended and retracted its proboscis, allowing it to ‘chew’ its food. The rows of short fringes on one surface of Louisella are thought to possible have been the animal’s gills. This worm has been reconstructed as a burrowing and carnivorous creature, and due to the grinding capability afforded to it by its proboscis, it likely ate animals of a relatively large size.

Louisella is currently held as a stem fossil on the lineage leading to the Priapulida worms, also known as the 'Penis worms’. I swear I am not making that up. These worms are very rare even today, with less than 20 living species known. They, like their ancient relative, are burrowing creatures which hunt other invertebrates. Fossils of priapulid worms are also rare, only a handful of Louisella specimens are known. What is far more common though are their distinctive shaped burrows, which are sort of an interlocking L-shape. The appearance of this type of burrows is one of the biostratigraphic markers of the start of the Cambrian period.

Louisella on the ROM’s amazing Burgess Shale website

Post link

#RealFossilHunter Tour – Part 4: Fossil Hunter Lottie meets Cambrian critter expert Dr Allison Daley

The incredible evolutionary explosion of weird and wonderful animals 500 million years ago has a special, trowelblazer-tastic history — have you heard of Helen, Helena and Mary Vaux Walcott, the Burgess Shale trowelblazers? If not, read this post! And that trowelblazing tradition continues to this day — which is why Fossil Hunter Lottie was just a tad excited to make her way to the University of Oxford and sound the day with Dr Allison Daley and learn all about her Cambrian Critters…

Read all about their day on TrowelBlazers: http://trowelblazers.com/realfossilhunter-tour-part-4-lottie-in-oxford/

Post link

Snab yours up before they are gone! https://paleopals.square.site/#rTZOwa

Adopt your own Opabinia regalis HERE!

Find more Anomalocaris themed goodies at: https://paleopals.square.site/#IShREF

Hallucigenia – Middle Cambrian (508 Ma)

It’s been too long since I featured something from the Burgess Shale. Last time, I featured Opabinia, along with an overview of the Cambrian Explosion and the history of our understanding of it. Today, we’re focusing on a little, inch-long invertebrate who lived alongside Opabinia, named Hallucigenia.

If you’ve ever seen a drawing or painting of a Cambrian landscape, it’s pretty likely you’ve seen Hallucigenia. It’s common as a backdrop animal in many portrayals of the Cambrian seas. Many of these tableaus are meant to evoke a feeling of unfamiliarity. They offer us a window to a much younger, alien earth. No fish swim overhead, and weird critters cover the seafloor. Hallucigenia is a perfect example of a weird critter. Then again, most of the fauna from the Cambrian period are. Most of the genera from the Cambrian have a story behind them, how we learned just how different they are from the things we know today, and this is no exception.

So, what is Hallucigenia? It’s weird, is what it is. This is normally the part where I, or any other amateur science communicator would reveal that it’s not actually as weird as it seems. The problem is, Hallucigenia really is that weird. It’s a soft-bodied worm with seven pairs of huge spikes on its back, and several tentacles underneath, perhaps used for walking. Also, it took us 50+ years to figure this out.

The Burgess Shale formation was discovered in 1909 by a man named Charles Doolittle Walcott. During his lifetime, he found and described hundreds of specimens from the Shale. However, Walcott was wrong about a lot of things. He misinterpreted several of the different fossils, including Hallucigenia. In fact, he didn’t even realize it was its own genus when he found it. For several decades, it was labeled as a specimen of an annelid worm called Canadia. It wasn’t until 1977 that paleontologist and personal idol of mine, Simon Conway Morris, recognized it as something very different. He reconstructed the animal more accurately and gave it its name, which, yeah, does come from the word ‘hallucinogen,’ because, I mean, look at this fucking thing.

Conway Morris didn’t get it quite right, though. For a while, we thought the spikes were on Hallucigenia’s underside, and that it used them to walk. In this interpretation, its tentacles would drift in the water and grab particles of food out of the air and carry them to its mouth. The accepted model has the spikes on its back, possibly as a defensive measure. We don’t know for certain that they were hard, since we haven’t found them preserved separately from the rest of the animal, like we do with other hard body parts.

This wasn’t the fault of poor fossil preservation—we have 109 specimens of Hallucigenia from the Burgess Shale, and they’re absolutely gorgeous. The problem is that this animal is so bizarre, so different from anything we have today. It’s hard to blame Walcott or Conway Morris for not being 100% correct about them right away.

So, now that we’ve studied these animals for so long, where does Hallucigenia fall on the tree of life? Good question. It’s a worm, but “worm” doesn’t really mean anything. All kinds of animals are worms, so what kind is this one? Scientists are torn, but two of the most popular hypotheses are that it’s either an early ancestor of velvet worms, or a distant cousin of what eventually became arthropods.

I could write an entire book about Hallucigenia and its cohorts in the Burgess Shale (in fact, one day, I want to), but I’m running late for some plans I have, so I’ll wrap it up here. Join me in a couple of days for… I don’t know. You ought to know I’m winging this by now.

Post link

Perspicaris – Middle Cambrian (508 Ma)

Today is a special day for a couple of reasons! 1) I get to talk about the Burgess Shale again, and, 2) Today’s animal is MSPTD’s very first requested animal! So, before I get into the writeup, I want to thank @futureimagineer843 for requesting this animal! This writeup was a lot of fun and I hadn’t actually heard of this one before xe mentioned it. Also, if you ever want me to talk about a specific animal, requests are something I am absolutely open to.

Our third trip to the Burgess Shale, the famous Cambrian fossil bed from British Columbia, examines a lesser-known and lesser-understood animal named Perspicaris. Using Perspicaris, we can really put into perspective how much of a treasure trove the Burgess Shale really is. This is one of the more rare animals from the Burgess Shale, and it’s known from only 202 specimens. For comparison, we have around 50 specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex, an animal found in significantly younger rocks and one of the better-known theropod dinosaurs. It might sound ridiculous to call it rare, but those 202 fossils of Perspicaris make up only 0.38% of the Greater Phyllopod Bed, where most of the Burgess Shale fossils have been found.

We don’t know much about Perspicaris. It’s a really weird animal. It’s really similar to a common Burgess Shale animal called Canadaspis (known from 4,525 specimens and making up about 9% of the organisms found), and we can extrapolate a bit about its appearance and how it might have acted from looking at it.

Perspicaris is a tiny arthropod. It was less than an inch in length (2-3cm), and bears more than a passing resemblance to shrimp and other modern crustaceans. We’re unsure of whether or not it was an early crustacean, a basal Euarthropod (the modern groups of arthropods), or from a family outside of that group that left no descendants. It’s definitely some kind of arthropod, but getting more specific is pretty hard. That’s the problem with the Cambrian fauna, and one of the reasons it’s so fascinating. This is when just about every modern phylum evolved, so when can we say they split for sure?

It’s also hard to say what the hell it was doing with that body plan. It had big eyes on the end of stalks and limbs that could have aided swimming. But, it didn’t have any claws or enlarged biramous limbs (limbs that branch into two different segments that are usually adapted to some special purpose), so if it was swimming, how did it eat? We know Canadaspis was a bottom-feeder, but don’t have any evidence for that in Canadaspis.

This brings up the question: How do we know all these things about prehistoric animals? We use a lot of methods to figure out all this. Since the Cambrian Explosion, most animals fill different roles in a given modern ecosystem. A lot of those ecosystems have parallels between each other. Let’s use the Great Barrier Reef and an African savannah as an example. I’ll simplify it, because food webs can be really complex and can make it hard to get what I’m getting at.

At the base of both ecosystems are vegetation. In the Reef, it’s algae and kelp. In the savannah, it’s grass. Then you have the herbivores who eat those things. So, dugongs/krill, and gazelles/wildebeests. Then you have the carnivores, which eat other animals, like tiger sharks and lions. A lot of animals have a parallel animal in other ecosystems, and we can apply that same logic to prehistoric ecosystems, too. We can figure out roughly where animals fall in prehistoric food webs based on the features they share with modern animals. Canadaspis has a lot in common with modern benthic (bottom-feeding) animals, so we can say pretty confidently that it was a bottom-feeder. But what do you do when you have an animal like Perspicaris, which has a mix of traits but nothing pointing definitively in any direction? You speculate. Throw stuff at your peers and see what sticks.

Perspicaris looks a bit like tadpole shrimp. They have plenty of differences, but in broad strokes they look alike. Now, tadpole shrimp are bottom-feeders, too, but doesn’t have eyestalks like Perspicaris. Our friend here shares that with internet celebrity called the mantis shrimp, which actively hunts larger prey. But it doesn’t have claws like the mantis shrimp, so…

You see the problem. That’s why paleontologists debate a lot. A lot of media likes to sensationalize these disagreements like they’re rap beefs or something, but no they’re usually just discussions about stuff where people don’t agree. You know, like, how science works.

Also, the media tends to latch onto the more outlandish stuff. There are plenty of folks around who still correct people by saying stuff like, “Actually, they found out that T. rex was a scavenger,” even though it was a theory that people only really looked at because Jack Horner liked it, and Jack Horner is, putting it lightly, a big fucking deal. That being said, there’s a truckload of evidence against that, and most scientists brush it off because Tyrannosaurus was built like a predator. Maybe I’ll talk about that someday.

So, what’s the deal with Perspicaris? In short: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. It’s a weird little arthropod with a really vague body shape, and it’s really hard to figure it out because it doesn’t really look much like anything around now. And the thing it does look like has specializations it lacks. They’re little mysteries in a field full of little mysteries.

P.S. I have to talk about this whenever the Burgess Shale comes up, but Perspicaris has really pretty fossils.

Post link