#hideaki anno

This is big fucking news.

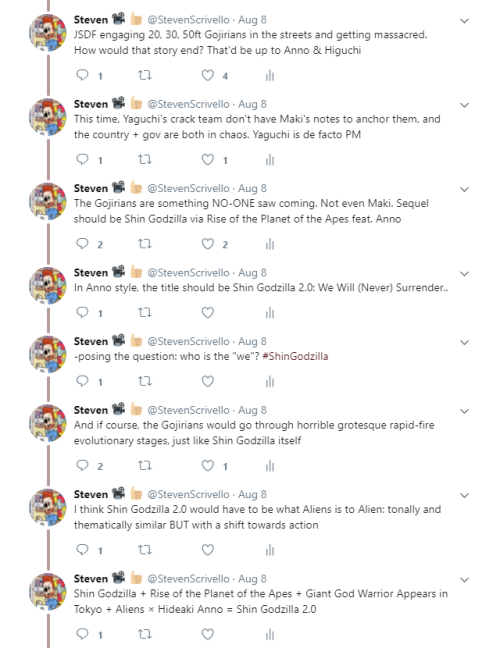

SoHideaki Anno,creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion,will be writing and directing the new Godzilla film by Toho in 2016.

The special effects will be directed byShinji Higuchi- who also worked on Evangelion and did the special Effects for the Gamera trilogy and is directing the new Attack on Titan films.

I am GOING INSANE OVER THIS NEWS THIS IS THE BEST THING.

PLEASE BE REAL

Post link

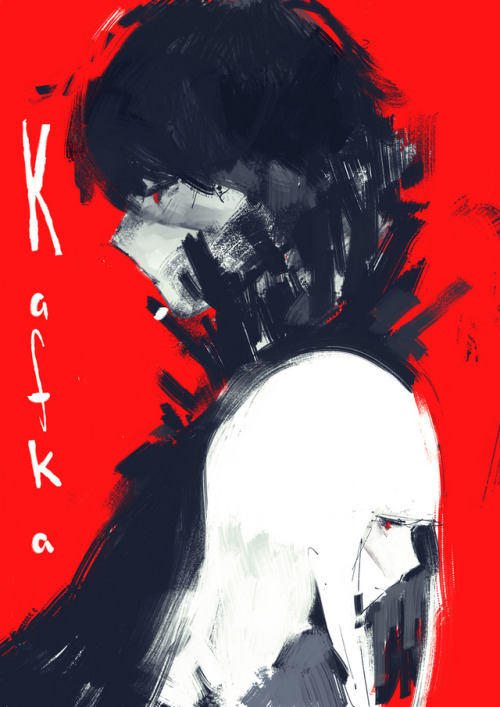

A crossover tribute I did for the “Blood Type : Blue Water Nadia x Evangelion ” artbook in collaboration with @evaimpact2016

Post link

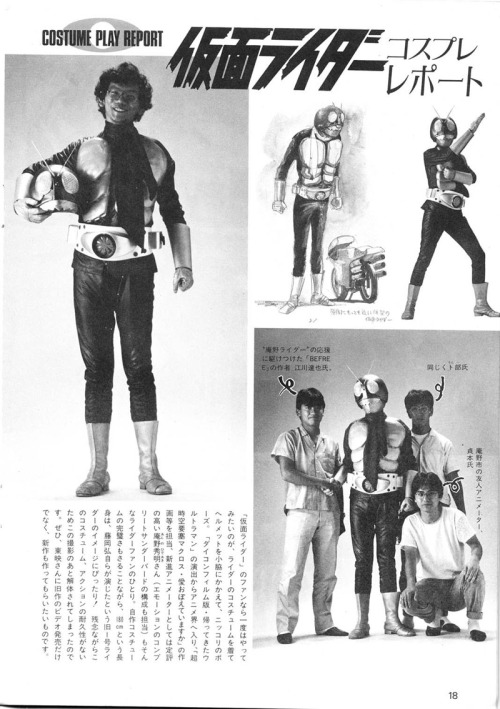

A young Hideaki Anno in his Kamen Rider 1 costume, famously referenced in his wife’s manga INSUFFICIENT DIRECTION.

Post link

Hideaki Anno’s Shin Kamen Rider (2023)

Reboot of the 1971 Kamen Rider series, which is the third reboot of a tokusatsu series to be adapted by Anno, following Shin GodzillaandShin Ultraman.

- Takeshi Hongo (Sosuke Ikematsu)

- Ruriko Midorikawa (Minami Hamabe)

- Hayato Ichimonji (Tasuku Emoto)

Not to be confused with Kamen Rider Black Sun (2022), which is a reboot of the 1987 Kamen Rider Black.

Shin Kamen Rider Trailer #2

Shin Kamen Rider Trailer #1

Post link

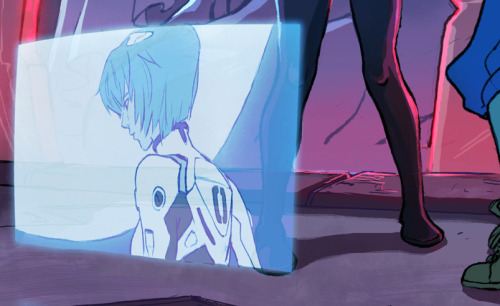

If you’re even a casual fan of Japanese animation (colloquially known as anime) you’ve probably heard of a few classics held up as the best of the medium; films and television shows whose place in the history of Japanese culture is widely regarded as secure: Akira,Cowboy Bebop,Ghost in the Shell,Spirited Away, to name a few of the most prominent. They all have their critics, but few would dispute their place as landmarks of the industry. But there’s one classic piece of Japanese animation however whose legacy is far more contentious and which sparks controversy even today. Like the aforementioned pieces it’s well-known and has been watched by many, but unlike them it remains quite controversial, beloved by some and derided by others.

I’m talking about Neon Genesis Evangelion,¹ Hideaki Anno’s 1995 post-apocalyptic series about teenagers who pilot giant robots (known as mecha) in a war for the survival of humanity. And in my opinion it’s actually one of the best and most important television shows of all time, animated or not.

(Spoilers ahead, though I’ll try to keep major revelations to a minimum.)

I realize that in making my claim, I’m setting myself up for criticism. The value (or lack thereof) of Neon Genesis Evangelion has been one of the most heated debates in anime fandom for decades. But even on the purely objective level of its influence on the animation industry, both in Japan and beyond, NGE and its subsequent spin-offs, sequels, and re-imaginings is a significant work worth consideration. Although the show is decades old now (the first episode aired October 4, 1995), I believe it’s still worth examining why the show’s so acclaimed and why, in my opinion, it’s still relevant today, in no smal part because of the lessons it still has to teach us about self-acceptance.

(An earlier version of this essay was posted 4 years ago here.)

Weaving a Story

Today, Evangelion is a major franchise, incorporating films, comics, video games, and more. But it all started with one TV show, Neon Genesis Evangelion, created by Hideaki Anno for Gainax. Even from the start, NGE was somewhat exceptional. In the early-to-mid 1990s when it was produced, most of the major animated shows on air (both in Japan and America) were heavily merchandise-driven and sponsored by either toy or video game companies. Nearly all were owned by a major studio like Toei or Toho. Conceived of by a single individual and owned by a small creator-run studio, Neon Genesis Evangelion was highly unusual and something of a creative risk.

The story of Neon Genesis Evangelion is, on first glance, nothing remarkable for Japanese animation. A group of teenagers are recruited by a unified global government to pilot giant robots (mecha) in a battle for the survival of humanity. In the process they have to face not only their deadly adversaries but also learn how to work together as a team, overcoming their many differences and personal issues. Gundam,Macross, and Hideaki Anno’s own Gunbuster had all covered similar territory before. But where NGE would go with its premise was far stranger, blending the well-tread concept of adolescent soldiers with theological imagery, Freudian and Lacanian analysis, and abstract writing that soon set the show apart from its contemporaries.

The show quickly caught the fascination of viewers. While Neon Genesis Evangelion started initially with solid but unexceptional ratings, it soon expanded into a massive pop cultural phenomenon as more and more people tuned in to find out what all the fuss was about, eventually reaching 25-30% of the targeted demographic.² The final two episodes, noted for their abstract nature and for seemingly leaving several plot threads hanging, prompted a highly polarized reaction. The follow-up movie The End of Evangelion, released a year later, divided audiences even further. As a consequence, despite Evangelion’s immense popularity and influence, the franchise remains one of the most controversial works to ever air on broadcast television.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s ending was, however, just one of its controversial aspects. Moral guardians raised complaints about the show’s frank (and frequently bleak) depictions of sex, violence, and mental illness, demanding networks censor its content. Critics such as Eiji Otsuka and Tetsuya Miyazaki accused Anno of “brainwashing” his audience and affirming, rather than criticizing, anime fans’ escapist tendencies. Yoshiyuki Tomino, the director of both GundamandIdeon, complained that Anno tried “to convince the audience to admit that everybody is sick” and that it “told people it was okay to be depressed.” Additionally, much was made of the show’s religious imagery, particularly due to the then recent sarin gas attacks by the Aum Shinrikyo cult, which like NGE utilized a blend of Western and Japanese religious imagery.

Other complaints centered on NGE’s main characters, many of whom were found to be unlikeable or unheroic. Many attacked the lead protagonist Shinji as weak and indecisive, unbecoming of the hero in a show aimed at adolescents. Some further asserted the character was an attack on the show’s audience and that Anno wanted to “punish” his audience for their anime-loving ways. The rest of the cast didn’t escape criticism either and were variably found to be cruel, schizophrenic, or perverse. All could easily be characterized as dysfunctional.

But despite the backlash against Neon Genesis Evangelion, whether it was centered on the show’s ending, its thematic elements, or its characters’ deficiencies, none of it seemed to put a lasting dent in the show’s influence or popularity. And a lot of that, perhaps, has to do with the time in which it emerged. At the time NGE was originally produced in the early to mid 1990s, Japan was in the midst of an extended economic downturn that would come to be known as the Lost Decade, following a major asset price crash in 1989. During this time, Japanese animation, like many industries, experienced a contraction, resulting in slashed budgets and an increasing reliance on merchandising and product placement to sustain both the studios producing the content and the major networks who broadcasted (and often owned) it.

In addition to these economic concerns, there was also a growing feeling in the 1990s that animation was a thing of the past, whose glory days were long gone and which only inspired passion in either adolescents or callow, sheltered men in their 20s or 30s. The content of most anime was regarded as puerile or derivative and hardly becoming of serious adult interest. The term otaku,³ a word that literally means “house” but was used to mean “shut-in,” quickly became shorthand for anime fans who spent their adulthood collecting memorabilia and memorizing lines from their favorite shows.

ButNeon Genesis Evangelion helped to change all that and to reclaim anime’s respectability. Breaking through the traditional animation fandom to a wider audience and owned solely by the creator-run Gainax, NGE was an invigorating shock to the industry, shaking it up and reviving interest in what had been regarded as a dying medium. Within a few short years, new creator-owned studios were cropping up across Japan, a trend which would continue well into the next decade and bear such fruit as Bones, manglobe, Ufotable, or Gainax’s own offshoots Trigger and Khara. The animation industry was expanding again and was beginning to boom overseas, in no small part thanks to the popularity and notoriety of NGE.

The new anime boom would also reflect its origins in a number of different ways. More than a few of the new shows to debut in the late 1990s and early 2000s were directly influenced and impacted by Neon Genesis Evangelion, including such notables as RahXephonandRevolutionary Girl Utena. More subtly, the starkly realistic depictions of violence and sexuality in NGE as well as its bizarrely surreal imagery encouraged many directors to try similar techniques, resulting in a shift in style throughout the industry.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s influence on later anime can be attributed in some ways to its technical sophistication. At its most basic, visceral level, NGE was startling to look at. Even compared with other Gainax works that had come before it, like Nadia: The Secret of Blue WaterorGunbuster, NGE immediately stood out as something unique in an increasingly homogeneous industry. The character designs of Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, strangely subdued yet striking and expressive, helped distinguish the cast while Ikuto Yamashita’s monstrous and biomechanical designs for the Evangelions did the same for the show’s mechs. Combined with the intense direction of Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Masayuki, and others NGE drew the eye right from the start.

The technical splendor wasn’t just limited to NGE’s art design or animation either. The voice talents provided by performers like Megumi Ogata, Kotono Mitsuishi, Megumi Hayashibara, and Yuko Miyamura gave life to the characters and helped audiences empathize with them, despite their dysfunctional and emotionally-wrought nature. Also contributing to the audio portion of Neon Genesis Evangelion was Shiro Sagisu, whose music swung significantly from jazzy to melodramatic and even to surreal, changing and evolving to match each scene with an appropriate mood. Assisting Sagisu was the vocal work of artists such as Yoko Takahashi, who made the show’s central theme, “A Cruel Angel’s Thesis,” a pop sensation.

But while the technical triumphs of Neon Genesis Evangelion certainly contributed to the show’s lasting appeal and influence, they’re hardly the whole story. For many viewers, the appeal of Evangelion went well beyond the surface, to narrative and thematic elements they felt spoke directly to them. Indeed, it is arguably NGE’s complex characterization, unorthodox narrative structure, and thematic depth which have made it stand out as one of the most legendary examples of Japanese pop culture.

A Cruel Angel’s Thesis

It’s not an exaggeration to say that essays—andbooks—have been written about Neon Genesis Evangelion and its thematic qualities. Most of this has been concentrated in Evangelion’s own native Japan, but the sensation has breached the other side of the Pacific as well, resulting in comparisons to the works of David Lynch and other Western directors. Contributing to this no doubt has been Anno’s own numerous references in NGE not only to native Japanese culture but to the West as well, with tributes to works like 2001: A Space Odyssey,The Andromeda Strain, and UFO found frequently throughout.

The most obvious thematic element present in Evangelion, at least to Western eyes, is its frequent allusions to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. It’s not hard to see why: the monstrous foes besetting humanity are “Angels” who shoot cross-shaped energy bolts, which the main characters fight with “Evangelions” (the Greek word from which “evangelism” derives). Coupled with other bits and pieces here and there referring to original sin, the will of God, and ancient Judaism, these details give Evangelion a strikingly religious appearance to Western viewers.

However, while they’re certainly the most obvious elements in Evangelion, the religious references are also easily some of the most transient and insubstantial. Although initially viewed as central to the plot by many Westerners, it has since been revealed that most of the Biblical references are there for styling rather than substance and were largely intended to make the show stand out. In many respects, the usage of the Abrahamic faiths in Evangelion is similar to the use of Buddhism in The Matrix or Egyptian mythology in Stargate: a bit of fun exoticism to keep things interesting.

That being said, the religious themes are not as vacuous as is sometimes alleged and the sheer number and obscurity of some of them indicates some real effort on the part of Anno. Each of the Angels, for instance, (which are called shito⁴ in Japanese, meaning “messenger” or “apostle”) are named after actual angels from Abrahamic mythology and their names, when translated from Hebrew or Arabic, often do indicate their nature in some way (e.g., Arael’s name means the “light of God” and it is an enormous winged being who attacks the characters with a beam of light). And while the use of the Kabbalah’s Sephiroth may be perfunctory, many other references to Jewish mysticism appear more meaningful, such as the Chamber of Guf or the duality of the Trees of Life and Wisdom.

Less obvious to Western eyes but possibly even more sophisticated are the references Evangelion makes to non-Abrahamic religions. There is, for example, the notable similarity between what the show terms “Instrumentality” and traditional descriptions of “egoless” nirvana in Buddhism (a religion also referenced by way of the Marduk Institute’s 108 dummy corporations).⁵ Japan’s native religion Shinto also shows its hand, most notably through the depiction of the Evangelions themselves, which Anno consciously designed after the monstrous oni of Japanese legend. All in all, while he may not have intended to portray a particular theological message, it’s clear that Anno put a lot of thought and research into giving Evangelion a suitably mystical appearance.

However, obsessing over the religious imagery in Evangelion obfuscates something far more important: Evangelion isn’t really about religion. Rather, where Evangelion’s thematic depth and complexity most clearly comes into play is psychology and philosophy of the mind.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is often described as a deconstruction of mecha anime. To a large extent that’s true, but it’s deconstruction is specific in outlook, focused on the psychology of its characters in the form of a question: just what kind of people would put the fate of humanity in the hands of adolescent children? And just what would that kind of stress and responsibility do to a child’s mind? In that regard, NGE is in far closer in kinship to Ender’s Game than to its natural predecessors like Macross,Gundam, or Gunbuster.

When the story of Neon Genesis Evangeliom begins, the world has already experienced disaster on an unprecedented scale. 14 years before the show begins, a massive apocalyptic event called the Second Impact devastated the Earth’s climate, precipitated global nuclear war, awakened the monstrous Angels, and resulted in the deaths of half of all humans on the planet. In response, civilization has been restructured and militarized in anticipation of an even worse Third Impact threatened by the Angels. To combat this threat, the secretive organization Nerv assembles biomechanical monsters of their own (the Evangelions) which, as it so happens, can only be piloted by teenagers.⁶

This is the kind of world people like Misato Katsuragi, Gendo Ikari, and Ritsuko Akagi live in and it’s the severity of their situation which ultimately shapes their actions. Although many of the adults, particularly Misato, wish they could let the series’ child protagonists lead a normal life, they know that’s not an option. As a result, the adult characters are driven towards a cold pragmatism that means, no matter how warm or compassionate they may act towards their wards at any given time, they’re still ready to sacrifice them when necessary.

This ruthless approach has its costs, however. The constant pressure to succeed, alongside the emotional whiplash they receive at the hands of the pilots’ supervisors and the repeated trauma they experience in combat results in each pilot’s gradual psychological degradation. Beginning as relatively competent and capable (if slightly dysfunctional) individuals, each pilot eventually succumbs to their trauma and breaks, causing them to isolate themselves from one another and resulting in a breakdown in morale which puts not only themselves but humanity itself at risk.

In keeping with this theme of psychological frailty and the ways in which we as people both intentionally and unintentionally harm those we care about, including those we care about, the series makes numerous allusions to the work of past psychologists and philosophers. Many concepts are mentioned specifically by name, such as the “oral stage,” “separation anxiety,” or the “hedgehog’s dilemma,” while others are alluded to more subtly, such as the Oedipus and Elektra complexes, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, or Lacan’s dichotomy of the constructed and ideal selves.

Hideaki Anno has himself said he researched psychology both before and during the production of Neon Genesis Evangelion and that many of the show’s characters are based upon both these concepts and his own experiences. He has, for instance, described the protagonist Shinji as a reflection of his own conscious self,while the emotionally withdrawn Rei is a manifestation of his unconscious, and the enigmatic Kaworu is his Jungian shadow. Altogether, the works of Freud, Lacan, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Jung, and Sartre have all been identified by staff or critics as influences on the show’s characters and plot.

One of the chief psychological themes in Evangelion is abandonment, particularly by those you love or have been cared for by. Throughout the story—in its past, present, and future—each of the main characters is abandoned by people important to them: their parents, their guardians, their lovers, their friends, etc. Invariably, this abandonment leads to a breakdown in identity and self-confidence, as each character is forced to redefine themselves from within after devoting so much of their identity to how they were perceived by others. Thematically matching to this issue of personal abandonment is humanity’s own abandonment by their unknowable creator eons ago, a detail alluded to occasionally as the story progresses. Like the individual characters then, humanity must learn how to manage and master its own fate when it has no one left to depend upon.

The Hedgehog’s Dilemma

These themes, however, would have little resonance were they irrelevant to the show’s human drama. It is to Neon Genesis Evangelion’s credit that they are not; each of the characters represent the show’s themes in both significant and personal ways. It is quite arguable then that it is the show’s protagonists, however controversial they may be either as individuals or an ensemble, which have truly allowed NGE to endure for decades as an icon of Japanese pop culture.

The most important of Neon Genesis Evangelion’s characters by far is easily Shinji Ikari, the pilot of Evangelion Unit-01 and the son of Gendo Ikari, the enigmatic director of the Evangelion program. At the beginning of the series Shinji is called to Nerv by his father, who abandoned him years earlier following the death of Shinji’s mother. Shinji hopes that this sudden call is for the purpose of reunion, but he is quickly disillusioned when his father reveals to him that he needs Shinji to pilot one of the monstrous Evangelions he’s built—a machine Shinji has hitherto never heard of—and to save humanity from extinction. Brokenhearted by his father’s coldness and terrified of the task he’s been blackmailed into performing, Shinji puts off his own desires and self-identity aside for the sake of pleasing his father and others, becoming the so-called Third Child.

Shinji’s a complicated character and one many find difficult to empathize with. He is self-consciously cowardly and phlegmatic, prone to self-criticism, and afraid of getting close to others for fear that they’ll reject him. At times he thinks seriously about running away from his responsibilities, but whenever he actually does he quickly returns, unable to commit to so blatant an act of rebellion for long. Despite this and despite his own reliance on others to define his value, Shinji does have his virtues: he’s thoughtful, easy to get along with, and proves remarkably skilled at piloting, even if he has no real passion for it.

Shinji’s commanding officer, Misato Katsuragi, is NGE’s most prominent adult character and (according to Hideaki Anno) the series’ deuteragonist.⁸ Loud, goofy, and irreverent, Misato strikes quite a different first impression than Shinji, but despite their outward differences they’re actually quite similar people with comparable issues, merely approaching them in different manners. Like Shinji, Misato feels abandoned by her father, who neglected her and her mother before his death years ago. But despite that Misato still yearns for his affection, manifesting her desires in the form of her relationship with Ryoji Kaji, a coworker and lover she admits resembles her father. And, also like Shinji, Misato fears getting close to other people for fear of being hurt, but whereas Shinji manages his anxiety by avoiding people, Misato does so by acting flippant and flirtatious in public, living lightly and maintaining only “surface level relationships.”

Shinji’s move into Misato’s apartment comes largely at her insistence and Shinji is initially quite uncomfortable with it, a feeling which does not subside when he learns she’s an extremely messy housekeeper and an alcoholic. But despite her irreverent personality, Misato turns out to be a deeply caring person who wants very much for Shinji to be happy and, over the course of the series, she tries to direct the development of Shinji as a good parent would, all the while concerned her own flaws make her an unsuitable guardian. Notably, these moments where the two of them bond are some of the most light-hearted in the series.

Although Shinji is the first pilot the series introduces, he is preceded by two others at Nerv. The first, Rei Ayanami, is arguably Neon Genesis Evangelion’s most popular (and certainly influential) character. Enigmatic and asocial to a degree that goes beyond mere awkwardness, Rei lives alone in a desolate apartment she doesn’t even bother to clean, close to no one but her pseudo-guardian Gendo Ikari. Because of her closeness to his father, who has raised her as his own daughter, Shinji initially sees Rei as a replacement for him. It soon becomes apparent however that Rei’s trust and faith in Gendo go well beyond that of a healthy parent-child dynamic. Obedient to a fault and unconcered for her own well-being, Rei causally throws herself into danger for Gendo and Nerv and comes across as emotionless to those around her.

But beneath Rei’s cold, ultra-stoic exterior beats a heart as capable of joy and sorrow as that of any other. Far from the robotic doll many assume her to be, Rei has a secret yearning for others to understand her and her them and, over the course of the series, slowly opens up to Shinji. But although she desires human contact, she doesn’t really know how to initiate it and she’s terrified of the possibility that there’s something about her that makes her fundamentally unlike other people.

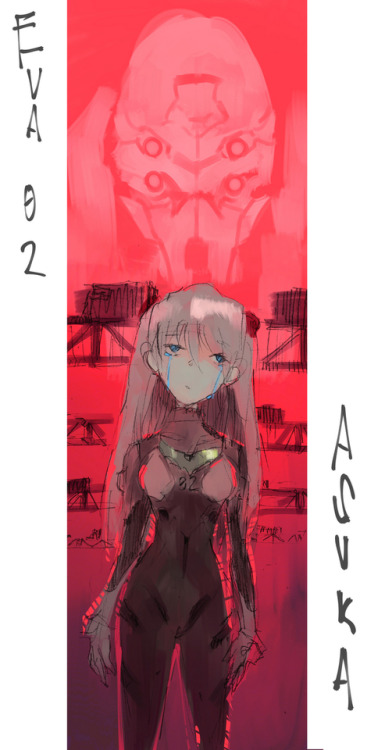

Asuka Langley Soryu, the third of the child protagonists to show up,⁷ strikes about as strong a contrast to Rei as one can imagine. Egotistical, loud-mouthed, and possessed of far more bravado than either Shinji or Rei, Asuka joins the cast about a third of the way through the show, after transferring from Nerv’s facility in Germany. Raised since childhood to be a pilot, Asuka prides herself on her skills and looks with disdain on Shinji’s self-deprecating nature and inability to recognize his own accomplishments. Already a college graduate and convinced she’s as much an adult as anyone, Asuka also proves precociously sexual, pining for both Misato’s lover Kaji and, to a lesser but still significant extent, Shinji himself, whom she frequently teases for attention.

Asuka is like Shinji a controversial character; people often look at Asuka and see one of two sides to her: a selfish jerk who bullies Shinji and Rei or an accomplished young woman whose confidence and inner strength makes her the real hero of the show. The truth, however, is that in many ways she’s both. Asuka really is brave—far braver than Shinji or even Rei, who doesn’t really fear death—and she’s definitely skilled. But she’s also prone to jealousy and vindictiveness, as well as a consciously manifested attitude of not caring for anyone. In many ways, however, her bravado is a cover for own insecurity, built upon the belief that no one really likes or loves her.

There’s a lot to admire about NGE’s characters, even with all their flaws and personality disorders. It’s easily got one of the most complex and diverse casts in anime and there has to be something said for the fact that of its four principal characters, three are female, allowing it to easily pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test (which it does). The characters each have their own virtues, which in a more easygoing series could make them quite endearing. Lead protagonist Shinji’s selfless and has a fairly noble streak, though it’s hidden deep beneath his own self-doubt and loathing. The adult Misato’s fairly protective of her young charges, at least insofar as she is allowed to be given the circumstances, and is also quite a bit more capable than many expect. Selfless Rei’s loyalty and discipline easily make her one of the most sympathetic characters in the series, even if she does sometimes come across as alien or inhuman. And there’s little question that the daring Asuka has enough chutzpah for the whole cast.

But it could also be argued that the complexity and harshness of NGE’s characters which ultimately make them work, even if at times they also make the show hard to watch. Shinji, Misato, Rei, and Asuka are not the idealized paragons of humanity you’d expect to find in most television shows aimed at teenagers, but they’re not the imaginings of a bitter misanthrope either. They’re deeply flawed, yes, and when they’re hurt they keep on hurting, but they also keep going and keep trying to find a way to live with others that doesn’t result in pain. It’s this idea, the recognition that people screw up and hurt one another but want to do better, that really enlivens the franchise. For all the reputed darkness of Evangelion’s story, it is in many ways idealistic, always hopeful that it’s characters might find a way to be happy. You don’t have to be broken, it says, even if you are damaged.

And it is that core ethos of qualified hope that elevates Neon Genesis Evangelion from just another mecha anime or even a deconstruction of mecha to something more. Something sublime and, in its own strange way, even inspirational.

The Sickness unto Death

At this point I feel it’s useful to provide some personal background. I first watched Neon Genesis Evangelion when I was in high school, sometime between my third and fourth years. My initial reaction was, I think, largely typical. The first episodes interested me and as the storyline moved forward and became more complex, I became more invested in the show’s events and characters. I even appreciated to some extent the bizarre and abstract final two episodes, though I’d hoped for a more conventional ending. Then, I watched The End of Evangelion, whoch left me shocked and dismayed at its harshness. I still cared about the series, but I felt more ambivalent as a result.

Over the next few years I continued to keep up with the Evangelion fandom to a small extent, checking out the rumors about the new movies and reading some fan fiction online, but I gradually drifted away. None of the fan speculation or fiction really seemed to scratch the same itch the original series had and eventually my interests in anime shifted more towards Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone ComplexandFullmetal Alchemist. Evangelion, as much as I’d enjoyed it before, fell gradually into the background of my life.

And then I entered college.

In my youth, I was generally regarded as a “bright” student, fawned over by teachers and regarded by my peers as either a genius or a “know-it-all,” depending on how much they liked me (or didn’t). As I entered the final years of high school it was clear that I was expected to excel in university. But when I actually began my college career I quickly faltered. Depressed, socially isolated, and exhausted from getting four to six hours of sleep a night, my grades slipped quickly and my social life evaporated. For awhile, I tried to deny my problems and ignore them, believing I could power through without help. Eventually, though, I had no choice but to confront my issues: I was put on academic suspension and my financial assistance was pulled.

I was devastated. I had no idea what to do. I didn’t know how to tell my parents, who I’d let believe I was doing fine. I didn’t know where to go with my life now that I’d failed to live up to the expectations I’d allowed other people to put on me. I didn’t even really know who I was anymore. If I wasn’t a brilliant student and child genius, who was I? In my own eyes I was worthless and contemptible.

Eventually, with the help of my family and friends, as well as staff from the university, I was able to make my way back to daylight. I began to undertake counseling. I went to community college to bring my GPA back up. I started talking more openly with my loved ones about my problems, even though I was worried it would make them think less of me. And I began to be more honest about my flaws and limitations.

It was also around this time, rather coincidentally, that I began to seriously revisit Evangelion. I was prompted, as much as by anything else, by the release of the new “Rebuild of Evangelion” films. After my brothers and I attended a screening of the second film’s release in early 2011 with several of our friends, the latter (hitherto unfamiliar with Evangelion) expressed interest in catching up with the franchise. Indulging them, my brothers and I rewatched the original TV series. To my surprise, I began to see the series in a new light. Where once I had simply been sympathetic to Shinji, Misato, Rei, and Asuka’s inner turmoil, now I felt deeply empathetic. Where previously the show’s harshness had at times alienated me, now it felt deeply relatable and truthful. And where earlier the TV show’s decision to focus on the internal psyches of its main characters instead of the plot had puzzled me before, now I felt as if I understood it completely. I even began to appreciate the theatrical finale, a film so brutal some regard it (falsely) as Anno’s revenge against fans angry with him for the original ending.

What had changed? Certainly not the show. Rather, it was my perspective. I possessed now of a viewpoint I hadn’t held earlier. I knew now what it was like to be full of contempt for one’s self, to be a defeated shell of a person who felt as though their value was slipping away or was already entirely absent. I knew what it was like to believe I was a failure in every meaningful way. In other words, I’d gained the perspective of a person suffering from depression. The same perspective as that of Evangelion’s principal characters as well as their creator, Hideaki Anno.

It’s hardly secret knowledge that Hideaki Anno was suffering from depression when he first created Neon Genesis Evangelion. The extent of his depression, however, was far graver than is generally recognized. When Anno began work on the project that would become NGE, he had already been suffering from severe depression for at least four years. In a statement released with the first volume of Evangelion’s manga (comic) adaptation Anno described himself as “a broken man… who ran away for four years, one who was simply not dead.” And while the production of NGE had originally been intended to break him out of a rut, the stress only compounded the severity of his condition. By the time of the show’s completion Anno was, by his own later admission, borderline suicidal.

No one’s ever said precisely what drove Anno over the edge publicly, but it’s widely agreed it had much to do with the production of his previous work, Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water. Originally conceived by Anno’s mentor Hayao Miyazaki in the mid-1980s Nadia was eventually handed off to Anno after Gainax made a bid for the project. Far gentler and family-friendly than NGE, the comparative sweetness of Nadia obscured a troubled production that saw animation work outsourced and Anno frequently butting heads with NHK, the series’ broadcaster, over the show’s content and creative direction. Coupled with rumored trouble in Anno’s personal life, the experience proved too much for him, driving him into the deep depression that would haunt him for most of the 1990s.

The roots of Anno’s emotional troubles may go deeper, however. Long regarded by those close to him as a lonely and eccentric oddball, Anno was socially withdrawn as a child, preferring to spend his time watching and recreating scenes from his favorite anime and tokusatsu to interacting with others, a choice he’d later say he regretted. In 1983, due in large part to his social isolation and inactivity at school, he dropped out of university and lived homeless for a time before he was discovered by Miyazaki and employed as an animator for Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The experience proved vital to his career and soon afterward he and a few friends gathered to form Gainax, their own animation studio. It was during this time that Anno directed Gunbuster alongside working on other projects such as Royal Space Force: The Wings of HonnêamiseandGrave of the Fireflies. For a time, he seemed happy. But then came Nadia and he withdrew entirely from his work and social life, before reemerging to work on Evangelion.

Anno’s turbulent life and emotional turmoil is reflected in the characters of Evangelion, many of whom enter the story damaged but apparently functional only to completely fall apart later on. Shinji is lonely and dependent when he first appears, but he still manages to form friendships and do what’s required of him. Misato may be an alcoholic with a mess of a home, but Nerv’s trust in her is rewarded time and time again by her effectual planning and coordination of her pilots. Rei’s cold and emotionally withdrawn, but her dutiful selflessness both inspires and attracts others to her. Asuka can be arrogant and reckless, but she’s also intelligent and capable of real kindness towards those she respects. Like Anno in the early days of Gainax, they all seem to be on top of things.

But just when it seems like the team’s getting the hang of things and finding their groove, disaster strikes. Soon, as one crisis mounts on top of another, from near-death experiences to being forced to hurt his friends, everything falls apart. Shinji’s newfound self-confidence shatters and he becomes even more needy than before. Misato’s constructed domestic bliss blows apart just as her own convictions are thrown into question by new revelations about her work. Rei becomes colder and more distant than ever before, withdrawing even from Gendo, the one person she trusts implicitly. And Asuka collapses into a pit of self-loathing despair, savagely lashing out at anyone who gets close to her. It’s ugly, it’s nasty, and it’s real.

This cycle of crash, despair, and recovery is not unusual for suffers of depression. Contrary to what is often thought, depression is not really something you have at one point in your life and then “get over;” it’s something that can shadow you your entire life, kept in check by momentary pleasures and good times but always threatening to surge and overwhelm you when things go awry, sending you into a spiral of self-hate and abnegation that can last for weeks, months, or even years. Friends and family help keep it in check, as does therapy and pharmaceuticals, but it never goes away completely. The only thing you can do is recognize the symptoms and do your best to confront them. You have to keep going. You can’t let your fears drive you to abandon the world. You must not, in other words, run away.

And really that’s what the characters’ struggles in Evangelion come down to: facing reality and acknowledging their flaws while also recognizing their own potential to overcome them and the painful struggle for acceptance we all, on some level, endure. The first instinct of every character in the series is to run away from their problems, to obscure them with outwardly derived duties, relationships, or purposes. Shinji and Rei both look to Gendo, Misato to her job, and Asuka to her pride as an Eva pilot, but all of them are running away and, as a consequence, are unprepared to deal with reality when it hits them flat in the face.

Or are they?

As Long As You Try to Continue to Live

It’s worth noting that when Anno created Neon Genesis Evangelion he didn’t initially set out to create a dark and cynical deconstruction of mecha anime. When asked what initially gave him the impetus to create NGE, Anno has said repeatedly that he originally meant to make a show more in the spirit of GundamorSpace Battleship Yamato, two of his favorite TV shows from his youth, but without the shackles inherent to sponsorship by a toy company, as was common practice for anime at the time. “I made Evangelion to make me happy and to make anime lovers happy,” he said in a 1996 interview, “in trying to bring together the broadest audience possible.”

But as pre-production on the series progressed (and his emotional state regressed) Anno became further disenchanted at the state of anime, concerned that fans were turning to it as a way to escape reality as he himself felt compelled to. “I wonder if a person over the age of twenty who likes robot anime is really happy,” he stated in an article for Newtype half a year before the series aired. This change in perspective, coupled with his resurgent depression, caused Anno to shift focus as he became more and more concerned with the characters’ emotional development, hoping that by the end of the series’ narrative “the heroes would change,” breaking away from their regressed emotional state and achieving the same emotional well-being and self-dependence Anno still sought for himself and which he felt his audience needed as well.

It’s this perspective of Anno’s—that anime otaku were and are caught in a kind of prolonged childhood—which has led to the impression that Anno hates otaku and believes their lives to be worthless. But the truth is that Anno’s thoughts on the subject are quite a bit subtler and more reflective than many give him credit for. Far from hating otaku, Anno counts himself among them and feels defensive whenever they’re derided by others. The issue, he thinks, is less that otaku are permanently stunted and more that they’re afraid or reluctant to open themselves to new experiences:

“I feel that otaku have already become common to all countries. In Europe, in Korea, in Taiwan, in Hong Kong, in America, otaku really do not change. I think that this is amazing. I say critical things towards otaku, but I don’t reject them. I only say that we should take a step back and be self-conscious about these things. I think it’s perfectly fine so long as you act with an awareness of what you are doing, self-conscious and cognizant of the current situation. I’m just not sure it’s a good thing to reach the point where you cut yourself off from society. I don’t understand the greatness of society, either. So I have no intention of going so far as to call for people to give up otaku-like things and become more suited to society. Only, I think there are many other interesting things in the world, and we don’t have to reject them.”

And that’s what I mean by Evangelion’s subtle, qualified idealism. Despite Anno’s frequent cynicism and troubled state of mind during the production of the series, it’s clear that at heart he’s a person who believes people can change and improve themselves. He’s someone who believes that, even in the worst or most desperate of situations, people can find happiness if they’re open to it. “As long as you try to continue to live,” one character states in The End of Evangelion, “any place can be a heaven… there’s a chance to become happy everywhere.”

It would certainly be easy to define the characters of Evangelion by their failures and—given the magnitude of their failures—it’s understandable why many do. After all, much of the series’ narrative is caught up (as I noted earlier) in deconstructing the kind of scenario typical of mecha shows and examing what really would happen if teenagers were put in charge of the world’s salvation. As such, as in other deconstructionist narratives (such as the Battlestar Galactica reboot or Watchmen), the characters screw up about at least as often as they succeed.

That being said, more often than not, when the characters are hit with tragedy or trauma, they eventually recover and bounce back. They’re definitely damaged and shaken by their experiences, but they keep on going anyway. As much as Shinji fears and abhors piloting he’s also someone who, when people are really depending on him, will almost always get right back in the cockpit and try to help. Rei may be over-compliant and lack any regard for herself, but she’s also capable of defying orders when she knows they’re wrong. And for all Asuka’s jealousy and grandstanding, she’s also a person deeply capable of love and self-sacrifice, who would die for those she cares about.

This ray of hope at the core of Evangelion’s story is made most clear in the television series’ original broadcast ending, wherein Shinji rediscovers his own self-value and the joy of living in a world with other people and declares that, although he hates himself, “maybe, maybe I could love myself. Maybe, my life can have a greater value.” But such idealism is even found in the much more outwardly harsh vision of The End of Evangelion. After coming face to face with the world he thought he desired—a world without pain or individuality—Shinji realizes that it’s also a world without happiness. “This isn’t right,” he says. “There was nothing good in the place I ran to, either. After all, I didn’t exist there… which is the same as no one existing.” Realizing this, Shinji chooses to return to the physical world he knew, even if it means feeling pain again.

The idea that joy and pain are in many ways coterminous with one another is hardly original to Evangelion; indeed, it’s a fairly important concept to Buddhism. But I’ve rarely seen the idea expressed in quite the same way as Evangelion, in a way that’s both fully formed and strangely life-affirming. Pain is inevitable, but so is joy. You’ll be hurt, but it’s better than never feeling anything at all and may only give you more appreciation for what you have. You may feel alone, but you’re not; everyone suffers in their life at one point or another, and you don’t have to carry that burden by yourself.

Reflecting upon and considering these themes through Evangelion, as I rediscovered it during a low point in my life, allowed me to appreciate it in a way I’d never been able to before. And it also helped me to move on with my life, to accept the losses I could never recover while also believing it didn’t mean my own life was over. Like Shinji, Misato, Rei, and Asuka, I didn’t have to be defeated by my experiences. I could keep on going. I didn’t have to run away. And that’s a message I believe everyone needs to hear at least once in their life.

Today, Hideaki Anno has found some peace of mind. He’s happily married, the head of his own production company, and he’s physically healthier too. He still suffers from depression—he’s not cured by any means and he probably never will be; depression isn’t that kind of disease. But he’s able to fight it now and to find the happiness he once believed illusory. He has the same hope he wanted his characters to find in Evangelion. And which I also feel I’ve found, in some small part, thanks to him.

¹Throughout this essay, Neon Genesis Evangelion or NGE refers to the original TV series, The End of Evangelion refers to its theatrical sequel, Rebuild of Evangelion refers to the series of rebooted films produced decades later, and Evangelion on its own refers to the franchise as a whole.

²Specifically,shōnen, meaning boys aged between 12 and 18.

³The term has since been adopted by Western anime fans, but in Japan the word does not necessarily refer to animation fans specifically but to anyone with an obsessive interest in something.

⁴Ironically, “messenger” is a literal translation of the word angelos from Greek—the origin of the English word “angel”—as well as the original Hebrew mal’akh.

⁵The numbers 8 and 108 are both significant in Buddhism. 8 refers to the Noble Eighfold Path to enlightenment. 108 refers to several things, including the number of beads in a Vajrayana prayer rosary, the number of questions asked of the Gautama Buddha in the Lankavatara Sutra, or the number of times Japanese Buddhist temples ring a bell on New Year’s.

⁶The reason for this is never fully explained. Behind the scenes, this was largely because of the show’s target demographic. In universe though it may be related to the secret nature of the Evangelions themselves, which have human souls.

⁷Deuteragonist is a term which means the second-most important character with whom the audience’s sympathies are intended to lie.

⁸Though referred to as the Second Child(ren) because she was the second candidate approved to pilot Evangelions, before Shinji but after Rei.

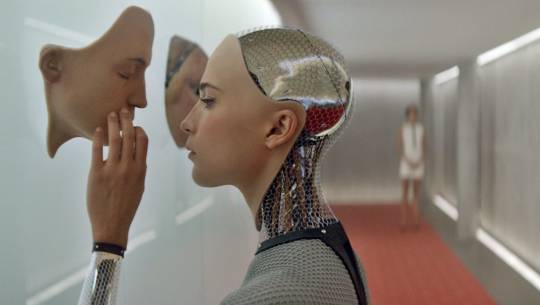

Ex Machina (2014) Showtime

Shin Godzilla (2016) VOD

Mimic (1997) Cinemax

The Host (2006) Prime

Jurassic Park (1993) HBOmax

Happy Birthday to director Anno, pictured here on the special effects set of Shin Kamen Rider!

Hideaki Anno by Moyoco Anno

Shin Godzilla releases theatrically across the UK today! Look out for limited one-day screenings and extended runs courtesy of Manga UK!

Happy one-year anniversary to Shin Godzilla!

Toho’s latest debuted nationwide in Japan on this day in 2016.

Post link