#jasper johns

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/5/16)

Jasper Johns (American, b. 1930)

Spring (1986)

Encaustic on canvas, 190.5 x 127 cm.

Private Collection

In 1985–86, the ever-eclectic Johns made four 75 x 50 inch encaustic paintings – Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter – which might be read as an allegory of his life and interests, as well as referencing a longstanding artistic and literary tradition of works about the four seasons and four ages of man.

The series dates from a period when the artist was moving between residences and in one of the many turning-points in his career. So, in a sense the paintings can be seen as a collaged form of “taking stock” when one is moving, and a taking stock that occurs at a certain point in life. Each painting has a similar structure. A silhouette – presumably of the artist himself – dominates the canvas, perhaps a evocation, perhaps not, of a 1953 Picasso painting (The Shadow) in which Picasso’s shadow falls across the floor of his studio. Each features art works by the artist or in his possession, as well as other cherished possessions. And the “season” of each is economically evoked in a few strokes, as in the streaks of rain here.

Critical interpretation of the works vary widely. John Russell in his NY Times review thought that “in ‘Spring’ there are many references to the way in which a given image can secrete a secondary meaning that turns its first one inside out. There is a version of the 19th-century visual conundrum in which a drawing of a pretty young woman can also be read as a portrait of an androgynous old crone. Fullbodied goblets, read in reverse, turn out to hold human profiles captive. A schematic drawing of a decoy duck relates to a well-known passage in Wittgenstein… If 'The Seasons’ does have a central meaning. it may well be that catastrophes can be borne, however awkwardly and painfully, and that a shattered self can be put together again. The potential of regenerative feeling, like the potential of painting itself, is ever-present, if we know how to get through to it.”

Jill Johnston, in her monograph “Jasper Johns: Privileged Information,” focusses on the theme of autobiography in Johns’ work when assessing the “Four Seasons.” Key to her analysis is her identification of the motif from the Isenheim Altarpiece: “It is even more difficult to see here since Johns deliberately obscures its presence by covering it with the cross-hatching that evokes the earlier painting Between Clock and Bed as well as the Corpse and Mirror paintings and others in that patterned, cross-hatched mode. The Isenheim altarpiece, an extremely large work with several "openings” (every time you “open” an altarpiece, you reveal another set of images – most open once; this one opened three times – was created for a monastic order which treated the victims of St. Anthony’s fire. In the Renaissance, patients were supposed to look at the repulsive figure in the painting, see in him the identification which he makes with St. Anthony, and through St. Anthony, an identification with the sufferings of Christ. Ultimately, this suffering would lead to salvation if the patient had faith. In Johns’ painting, the redemption which would come through religious belief is replaced by a redemption which comes through art. Johns does something unusual with this because he places himself in the position of victim and the position of savior. At the same time, his literal presence in the painting takes the form of a shadow, an insubstantial form with no body. The Four Seasons would therefore seem to unite two themes of Johns’ work: the theme of denial of self (in earlier works, denial of objecthood and denial of meaning, as when he uses paints the letters “red” in blue paint) and the identity of self (object, word, meaning). Whereas the early paintings express these themes in linguistic or semiotic terms, the later paintings express them in a more personal and autobiographical mode, making the fundamental issue throughout Johns’ work the question of where does identity come from.“

Johns is one of the featured artists in the the MWW exhibit/gallery:

* American Moderns V: Pop Goes the Art World

Post link

Portrait of Jasper Johns for the New York Times with art director Jennifer Ledbury and Deborah Solomon.

Post link

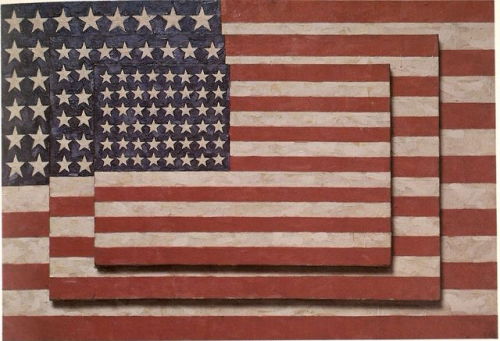

Museum wanderer Amber harmonizing swimmingly with Jasper Johns’ Three Flags in her snazzy Francine Dressler tee.

Post link

Wishing you a happy Fourth of July!

Installation view of Where We Are: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1900–1960 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 28, 2017–). Photograph by Ian Allen

Gotta love JJ ❤️

Post link

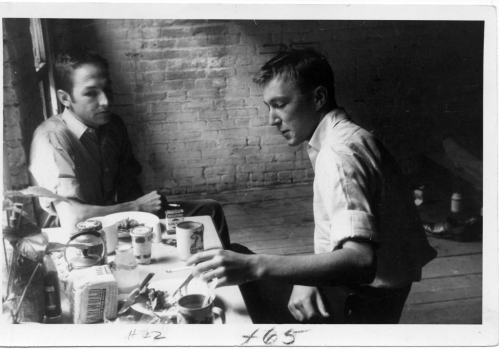

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Check out Jonathan Katz’ beautiful essay from Significant Others: Creativity & Intimate Partnership,The Art of Code, for a unique look at LGBT couples in art, as well as some perspective on the influence of Rauschenberg and Johns’ relationship and sexualities on their respective work and careers.

Post link

Jasper Johns,Three Flags (1958) via Whitney Museum.

THE OVAL OFFICE BY JON RAFMAN IN THE STYLE OF JASPER JOHNS.

In Fall 2020, A Lifetime Retrospective Dedicated To Jasper Johns Will Be Presented Simultaneously In New York And PhiladelphiaIn an unprecedented collaboration, this major exhibition is jointly organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of ArtOctober 28, 2020–February 21, 2021#JasperJohnsThe most ambitious retrospective to date of the work ofJasper…

NO WHERE THERE: Abstract Landscape Painting

“What you see is what you see," Frank Stella once said of his paintings, meaning they referred to nothing outside of themselves and represented nothing beyond pigment and canvas. Yet many of Stella’s paintings were named after places, local and far afield—Firuzabadand Hampton Roads, Gran CairoandTelluride. This seeming contradiction is not unique to Stella—many artists of the post-war period who worked in an exclusively abstract mode, allude to locations, places, or geographies in the titles of their works. These range from geographically-specific sites (Mahoning,Villa Borghese), to more generic typologies of place (Basque Beach) and topographical features (Cataract, Mountains and Sea). These works are non-figural, and as such, they do not accord with the art historical genre “landscape,” at least not in the traditional sense.

Are these evocations of place, in fact, equivocations—a reluctance to commit to absolute abstraction, or do titles like Basque Beach amount to a personal association imposed on an painted surface that has no necessary relationship to an actual or conceptual place? To put it more crudely, is there a where there?

While they are clearly not engaged in empirical description or mapping, certain abstract paintings seem to follow the contours of places alluded to in titles or be guided in their formal choices by qualities observed at those places. For example, the high-key palette, overall bright tonality, and wave-like forms of Helen Frankenthaler’s Basque Beach would seem to permit of a quasi-figurative reading of the work. Speaking about her breakthrough work, Mountains and Sea (1952) Frankenthaler parsed the picture’s representational and abstract qualities:

I painted Mountains and Sea after seeing the cliffs of Nova Scotia. It’s a hilly landscape with wild surf rolling against the rocks. Though it was painted in a windowless loft, the memory of the landscape is in the painting, but it has also equal amounts of Cubism, Pollock, Kandinsky, Gorky.

Elsewhere she referred to her paintings as “abstract climates.”

DeKooning described the large paintings he made in the late 1950s bearing place names like Merritt ParkwayandParc Rosenberg as “emotions:”

The pictures (I have) done since the ‘Women’, they’re emotions, most of them. Most of them are landscapes and highways and sensations of that, outside the city – with the feeling of going to the city or coming from it.

For both Frankenthaler and DeKooning, abstraction may mean non-representational, but it doesn’t mean evacuated of memory. The registration of memory, like the gestural brushstroke, is a relic of the artist’s interaction with the canvas, and not a form of “meaning” imposed from without.

In 1965, both Helen Lundeberg and Roy Lichtenstein painted pictures that they referred to as landscapes, but which bordered on abstraction. By calling her radically-simplified , yet figurative picture Landscape, Lundeberg uses the term to suggest an elemental distillation or essence of place. Lichtenstein’s picture is predictably trickier; an image of the horizon executed in benday dots and cropped in such a way that it verges on Rothko-like abstraction, it clearly invokes “landscape” as a meta-category, (like his contemporary images of ruins and brushstrokes) from an ironic distance.

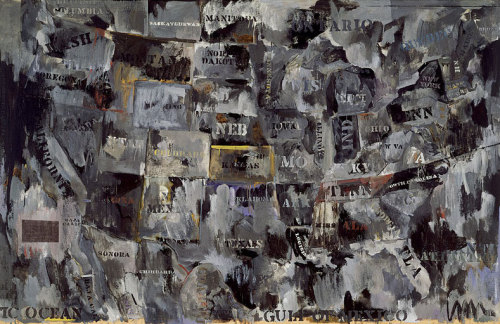

If traditional landscape painting was in some meaningful sense involved with a descriptive or empirical mapping of place, then to what extent can pictures of maps be considered abstract landscapes? Jasper Johns’ recreation of a map retains the form of the visual artefact on which it is based and the stenciled labels are correctly applied, but a cloud of abstract-expressionist brushwork undermines the purpose of the original by reducing it to a merely optical experience. Ed Ruscha proposes a similar conundrum with less Wittgenstein und Drang when he offers us two street names and no other points of reference as either a “view” of L.A. or a detail of a map.

Post link

This Memorial Day, Monday, May 27, the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries will be closed in celebration and remembrance of those who have served in the military.

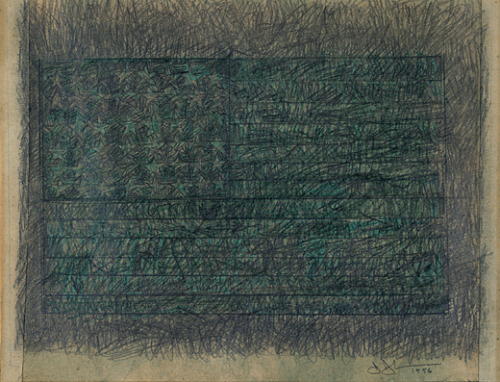

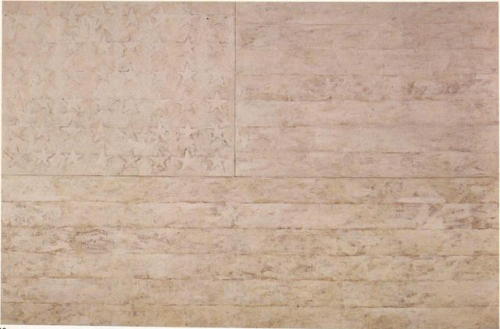

The works you see here are by Jasper Johns and Norman Rockwell. Jasper Johns’ Three Flags (1958) and White Flag (1955) are only two of the many works by the artist that featured the American flag. Johns gave a new form to a familiar symbol that many were starting to look over, causing people to look at it with fresh eyes.

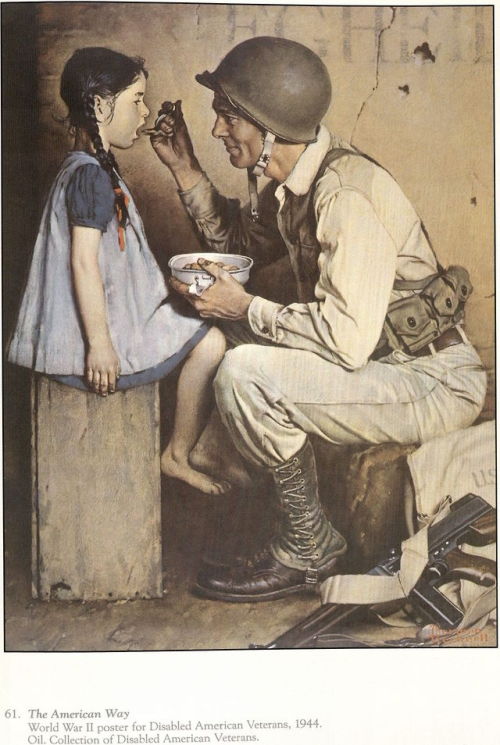

Norman Rockwell was a prominent artist during both world wars, showing his support for the armed forces through his art. The oil painting with the little girl handing the soldier a flower is titled The Tribute. This image was featured on the cover of Judge in August of 1918, shortly before World War I ended. The American Way (1944) is a World War II poster honoring disabled American veterans.

Come view more works by these artists, as well as other works about art and the military, when the reading room opens on Tuesday, May 28, at 1:00pm. These images are from:

Francis, Richard. Jasper Johns. First ed. Modern Masters Series ; v. 7. New York: Abbeville Press, 1984.

Rockwell, Norman, and Rockwell, Thomas. Norman Rockwell : My Adventures as an Illustrator. New York: Abrams, 1988.

Rockwell, Thomas. The Best of Norman Rockwell. Philadelphia, Pa.: Courage Books, 1988.

Thank you for all those who have served and those who continue to serve our country. Thank you to the artists who honor the members of our military forces with their work.

Post link