#kirsty logan

Continuing my personal mission to make everyone obsessed with this book - so happy it’s a #RiotRec!

Post link

Nine Books I Want You to Read This Summer

If you haven’t read these books yet, you need to, and you need to do it soon. These are some of my favorite books by women about women that I’ve read over the last year or so, and they’re the ones that have stuck with me. I firmly recommend all of these, in no particular order.

A contemporary retelling of Jane Eyre set in NYC in 2001, Re Jane follows the titular character through not only her recognizable past but through a new future that tackles extended family relationships as well as contemporary woman- and adulthood.

The Girls from Corona del Mar, Rufi Thorpe

Rufi Thorpe’s debut novel is out in paperback this summer, following the lives of Mia and Lorrie Ann, childhood friends whose stories diverge and meet again over the course of what feels like a young lifetime. As both women struggle with bringing family baggage into their adult lives, they learn what the reality of adult friendship can be.

After her father died, Charley Bordelonfound she’d inherited a sugar cane farm in rural Louisiana, so she packed up her life and her daughter to move from Los Angeles to reunite with her childhood family and friends. As she learns, moving back home after many years comes with its own challenges, not limited to the struggle she faces on the farm.

The second book in Tana French’s tenuously-linked Dublin Murder Squad series, The Likeness follows Det. Cassie Maddox as she revisits her Undercover days after the body of a young woman is found, with her former false identity - and a practically identical face. Cassie finds herself deep undercover after taking back on the identity, trying to determine who the killer is without finding herself in trouble.

Based on Bolick’s widely-publicized Atlantic article, Spinster is a non-fiction exploration of not only what it means to be a single woman in the 21st century but how women push to distinguish themselves in careers, particularly as writers. She ties in the stories of well-known “spinster” women writers from the last few centuries, giving historical context to what turns out to be a not-so-new struggle.

The Gracekeepers, Kirsty Logan

Inspired in part by Scottish myth, Kirsty Logan’s ethereal debut tells the alternating stories of North, who travels with a floating circus, and Callanish, a gracekeeper who presides over a watery cemetery. As circumstance brings them together, both young women wonder if they’re really satisfied with where their lives have taken them thus far.

Charlie Wong is a young dishwasher in Chinatown who dreams of a life that will let her see the rest of the world, or, at least, the rest of New York City. When she gets a receptionist job at a dance studio uptown, she gains confidence in herself, but as her mother’s talent as a ballerina comes out in her own life, Charlie must learn how to balance the two halves of her life.

Roxane Gay’s debut novel follows Mireille, visiting her Haitian family with her husband and young son. When Miri is kidnapped for ransom and her father refuses to pay, she is subjected to the brutalities of captivity and must rely on herself to survive. Not for the faint of heart, An Untamed State is a gut-wrenching insight into an infrequently-mentioned topic.

Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng

Celeste Ng’s debut novel begins with the death of teenager Lydia Lee in 1970s Ohio, and unravels a story of what happened to her and how her family deals with it. This is the story of a mixed-race family with some secrets laid bare and some secrets still to come.

Post link

FellowFemale GazerKirsty Logan’s debut novel, The Gracekeepers, is darkly dreamy and utterly absorbing. Reading it feels like swimming in a cool blue sea. It features a floating circus in a drowning world sprinkled with archipelagos, the last earth on Earth, and a hallowed grace-yard with totem birds marking periods of grief by slowly starving in their buoyant gilded cages. This novel is a gorgeous shard of sea glass washing onto a chilly northern beach. It’s a bit like a richer, more compelling Waterworld.

The Gracekeepers primarily unfolds through the eyes of two heroines–North the fiery bear girl and Callanish the somber gracekeeper. Their stories kiss and diverge like waltzing lovers. A few other characters get their chance to shine in their own POV chapters, which I’m usually wary of but it ended up working beautifully. Everyone is struggling with their own bone-deep desires.

Logan gives us a wonderfully strange and sad post-apocalyptic world with humanity split into two factions–the earth-bound landlockers and the sea-bound damplings. Fear and prejudice fuel their interactions, and the damplings, like North, are clearly the disenfranchised ones. This book is built on binary conflicts. Can one form one’s own identity, outside of a binary? Are there paths between binaries, and if so, how safe are they to trod?

1. Congratulations on your novel debut! Would you share the origin story of this lovely tale?

Thank you! I’ve spent so long living in this weird, dark dreamy world, and it’s a treat to finally be able to bring other people in.

It began with a small, strange image. About a year after my dad died, I was out on a boat with my uncle. We’d both suffered a terrible loss – me of my dad, he of his brother – but we’d never spoken about it directly. I happened to see floating buoys with lights inside that looked like birdcages. So my mind began to wander: why would there be birdcages at sea? Grief was still very much on my mind, as well as my secular lack of a structured mourning, and a lack of a way to discuss it, and so I thought that perhaps the birdcages would be grave markers, and the lifespan of the birds inside would mark the mourning for the person who had died. The whole novel arose from that tiny, personal place.

2. Who was/is your first reader?

My partner, Annie. I read the entire novel to her, chapter by chapter, as I was writing it. Sometimes there would be a cliffhanger at the end of a chapter, and she’d then have to wait weeks until I’d finished the next one! She’s now heard about three different versions of the book, as it changed with each edit. I like to think that there’s this first-draft ghost-book that only exists in mine and Annie’s imaginations, because we’re the only ones who heard it.

3. I loved all the gender-play with the circus–the subversive clowns, the sensual glamours, the wild costumes and make-up, the androgynous performances. Am I right in believing all this gender-fucking reflects intentional themes of freedom and identity?

Very much so. It’s about freedom, and about blurring boundaries, and about not having to just choose one thing or another. There are lots of different binary conflicts in the book: land/sea, male/female, gay/straight, security/freedom, wildness/domesticity. A lot of the conflict in the book is about the characters feeling they have to choose one and sacrifice the other.

By the end, I hope that the characters (and maybe the reader) have begun to feel that their world (and maybe our world) is not just a binary choice. If we want, we can choose one thing. But we can also flip between the two, or we can choose neither and follow a third path we have marked out ourselves.

I think partly that comes from my own life. I’ve had both girlfriends and boyfriends, and each time I had a new partner people would ask whether I was ‘gay now’ or 'straight now’. And the answer was yes and no. I’m a monogamous person by nature, so when I was with a man I wasn’t interested in women – but I also wasn’t interested in any other men, just the one I was with. So now I’m with Annie, and it’s not that I’m a lesbian and not interested in men, it’s that I’m not interested in anyone except her. But no matter who I was with, it didn’t change my identity. The person you’re sleeping with doesn’t have to change you if you don’t want it to.

I was born in England to Scottish parents, so I didn’t properly belong there; and now I live in Scotland but have an English accent, so people don’t perceive me as being properly 'from’ here either. I’m from both places, and also neither entirely. I’m a cis female, and I like dresses and lipstick, and generally I’m happy to present as female. But that doesn’t mean I want to always look typically female. I don’t think the way I present myself changes who I am inside, because I don’t want it to. We decide who we are, and the freedom to present ourselves however we like doesn’t change that. I’m quite happy to hold all my contrasting identities simultaneously.

4. When I started reading, I assumed that North and Callanish were the only point-of-view characters, so I was surprised and honestly a little wary when I turned a page and met a chapter from the clown Cash’s POV. I’d already grown attached to North and Callanish, and I believe it’s a risky choice to use multiple POV characters, but now I can’t imagine the novel without those secondary character chapters–especially Red Gold’s and Avalon’s. Did you always intend to tell the story from multiple POVs, or did that come about during the writing process?

This is very much a short story writer’s novel! Short stories come more naturally to me, so this was a way for me to approach the massive undertaking of a novel while still keeping to my own natural rhythm.

Each chapter is its own little tale, and I wanted each character’s point of view to subtly undermine the one that came before. So in one chapter we have the clowns observing the ringmaster’s wife, and thinking how cruel and silly she is; and then we have the ringmaster observing his wife, and of course he’s thinking that she’s sweet and beautiful and sensitive. There is no single truth, not about the world and not about the people in the world. We are all complex. We all have multiple selves. Which self we present is different depending on our company, so it made sense to me that each character could be described from multiple viewpoints, and each of those would be true – even when they were contradictory.

5. So Avalon was the closest thing to a classic villain in The Gracekeepers–a pregnant Machiavellian beauty with a burning coal heart and desperation wafting from her like the smell of strong drink. I’m particularly fond of lady villains, flawed women, “ruined” girls, and the like, so of course I hate-loved Avalon. She reminded me a bit of Lady Macbeth, aka one of my favorite characters of all time. I was particularly enamored with the idea of a pregnant woman doing and saying the things she does; that clash of growth and destruction, and how it contradicts the popular image of pregnant women as life-giving beatific figures. I clearly don’t have an actual question–I just want you to dish about Avalon a bit. Do you agree with my assessment of her?

Avalon was the most fun to write. She’s the wicked stepmother from 'Snow White’, she’s the biblical Eve, she’s Cruella de Vil. She’s seductive and full of rage – and still, she’s a loving wife and a nurturing mother-to-be. She loves her family, and everything she does, she does for her own good reasons. She can be all of these things, just as we can be myriad and contradictory things. Becoming a parent doesn’t necessarily make you a good person. I very much want children, but I don’t think it’s an intrinsically noble act.

Most people I know are many different things. This book began with the loss of my dad, and he was a contradiction too. He was an alcoholic, self-destructive, couldn’t hold down a job. But he was also a loving father who continued to support me financially and emotionally, even through his darkest times. Even as he couldn’t properly look after himself, he helped other people by working for an addiction charity. He never settled to a career, but he was massively inspirational in my career. His funeral was packed with people I didn’t even know he knew – people whose lives he’d touched, who had good memories of him. Recently his university girlfriend got in touch with me, and she had such strong and affectionate feelings for him even though she hadn’t seen him for thirty years. He was a great man, but also a deeply flawed and troubled man – and at the same time, he was a regular guy, nothing special, someone you’d pass in the street and not even notice. Every single one of us is just a regular person, but is also vitally important.

6. I really enjoyed how you used the clowns; how they ended up being central to the plot. I was terrified of clowns as a child, and as I grew up that terror evolved into just being creeped out by them. What clowns are (ambiguous) and what we project onto them (fury, anarchy, sadness) is exactly what’s so creepy about them. As you say: “Dough knew that clowns made perfect scapegoats, because what’s scarier than a clown? They stand for money and hunger, sex and rage, loss and loneliness, displacement and death. They stand for everything, and they stand for nothing.” Did you ever fear clowns as a child, and have you encountered any readers who are afraid of your clowns?

I hate clowns. Properly hate them. They’re scary and sinister and I have never found them amusing, not even as a child. I’m creeped out by painted faces and masks and anything that hides people’s faces in a grotesque way. But of course, that’s why I’m so fascinated by them. One of the weirdest things about being a writer is that you’re constantly exploring things that disturb you, because that’s where your emotional truth hides.

When I researched the history of circuses – because there’s loads of research in this book, though I don’t think it really shows; I researched circuses and English folk traditions and naval superstitions and different types of boats and which crops grow in different climates and which landmasses would exist as islands if the world did flood – I found that clowns have always served as scapegoats. Their tradition goes back to court jesters and fools. The common people (the 99%, as we’re now called) would be angry at what the kings and lords did, at their flaunting of wealth and charging of taxes. But it was too dangerous to criticise or mock those in power, or the platform to do so just didn’t exist. So instead there were the jesters and clowns: figures of fun who made themselves look silly so we could all scorn them and feel superior to them. Also, the fools and jesters could talk about political situations in a way that no one else could, because they dressed it in a funny story. We don’t just mock the clowns because they’re silly – we mock them because they stand in place of those we really want to hate. It’s the same with nursery rhymes and fairy tales: they seem like fun little stories, but many of them are a sneaky way to criticise those in power.

7. In our interview for The Rental Heart, we discussed your teen years and current life in Scotland and how it informs your literary aesthetic. Since The Gracekeepers is set in a fantasy post-apocalyptic world, how did your Scottish identity influence the atmosphere/settings, if it did at all?

Scotland is so inspirational to me. There’s the folklore and fairytales, of course, and so many of those stories (selkies,kelpies, mermaids) are based on the sea. No matter where you go in Scotland, you’re never more than 40 miles from the sea. I’ve written so much about Scottish folklore, but I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface. Folklore is the well I keep returning to, and I don’t see how it could ever run out.

So there’s the sea part, and in Scotland we also have the tradition of the ceilidh, a social gathering with music and wild dancing. It’s a very sociable country, and people are much friendlier here than any other place I’ve visited. Scottish folk – and those in Glasgow in particular – will always help a stranger, or chat to fill the silence, whether you want them to or not!

I love that raucous, sociable aspect: drinking and music and dancing until dawn. But I also love the other side of Scotland: days of silence and watching the tide breathe in and out. I try to bring that contrast, that non-conflicting contradiction, to all my writing. I’ll never stop being inspired by this country.

8. Are you superstitious in any way?

I’d like to say no, but I did develop some little superstitions when writing this book. I wrote the first chapters on a series of writing retreats along the Scottish coast, and at one point I was in a little east coast fishing village called Cellardyke. While I was there I visited an antique shop and bought a brass compass. From then on, I always had to make sure the compass was pointing north before I could begin the day’s writing. That was very much a book-specific superstition, as I haven’t done that for any writing since.

9.If you could pick a classic fairy tale to retell (that you haven’t already), what would it be?

’Kate Crackernuts’, a Scottish fairytale about a girl who isn’t pretty or demure, but who gets her happy ending by being clever and resourceful. It also features a fairy ball, which has a contradiction I love: it’s beautiful and glamorous and happy, but it’s also destructive and can ultimately kill you.

10. Now, please do share a little about your third book, the forthcoming story collection, if you don’t mind. I can’t wait to see it in print!

Thank you! I’m excited about it – I love writing short stories, and they’re more fun to read at events than novel extracts because you get to share a fully-formed piece rather than just a sliver. Also, the collection is written in thirteen different voices, so that’s more fun to perform as each story has such a different mood.

The book is a collection of linked stories called A Portable Shelter (due out in the UK in August). It’s inspired by Scottish and Scandinavian folk tales, and it’s all about loss, identity and the purpose of stories.

To be honest, I’m already getting excited about starting Book #4, which will be another novel. This September I’m off for a one-month writing retreat to a forest in the middle of Finland, where I’ll start writing it. I’ve been planning three possible novels, and I don’t know yet which one I’ll actually write. But it’s nice to have options!

Conversation by Dawn WestandKirsty Logan.

“Motive is never easy. Sometimes it occurs to one only later.”

When I was twenty-four, I met a girl called Suse. I liked her. I really, really liked her. She had stretched earlobes and smelled of men’s aftershave and made me mix CDs. She studied medieval history and wore both her dead parents’ wedding rings.

But I’d just come out of a four-year relationship with a man, a merchant navy sailor who was 6'4" and tattooed and from the Scottish Highlands and not at all the sort of man people who know me would think I would go out with. After we broke up I was confused and trying to figure out who I was. I didn’t know if I wanted to be in a relationship with a man, or a woman, or both, or neither.

I felt lost, cut loose from the moorings of a steady relationship, desperate to feel grounded – and at the same time frantic-thrilled to be seeing new people, eyes bright, constantly drunk on excitement. I was, if I’m honest, temporarily insane. I spent half my time with Suse telling her I didn’t want a relationship, and half the time treating her like my long-term boyfriend. It was weird. I was weird. She broke it off.

Then I met a girl called Suz. I wondered if god or fate or the universe was mocking me. She had bright red hair and wore lip-gloss and studied abnormal psychology. I liked that she was called Suz because I was still hung up on Suse, but it turned out I didn’t like anything else about her. I broke it off.

After that I met a girl on a gay dating website. We chatted online and liked one another, so we arranged to meet. Oh wait, I thought – what’s your name? Susie, she said. Then I knew for sure that god and fate and the universe were all mocking me. Apparently I was going to meet every lesbian called every variation on the name Susan in all of Glasgow. But then Susie and I stayed together for four years. I came to think of the Suse and Suz as pseudo-Susies, stepping stones leading me to the ‘real’ Susie.

Such a pleasing story! Beginning, middle, end. But I know it wasn’t like that, not really. It was life, and it was messy, and it’s only now, six years on, that I can look back and see the shape of it.

“By their nature words are imprecise and layered with meaning – the signs of things, not the things themselves. It’s difficult to say who’s in charge.”

’Milagro’ is one of the simplest, most intimate, and most beautiful episodes in all nine seasons of the X-Files. On re-watching it to write this essay, I alternated between absorption and cringing. Absorption because it’s such a visual treat, from the tender close-ups of Scully’s beauty to the softly-lit church to the final pulsing heart. Cringing because holy shit it represents the aesthetic and life goals I never realised I had: the solitary writer living in a room with just a chair, table and typewriter; the heartbeats, the catholic paraphernalia, the overwrought prose (Grief squeezed at her eggshell heart like it might break into a thousand pieces) – these are things I’ve done, things I’ve written. I basically watched this episode at the age of 20 and forgot about it, then my subconscious spent the next decade obsessing over it.

But it’s only now that I see that. That use of symbolism as story – I’ve built my whole career on doing that. Last year my first book was published, a collection of twenty short stories. All the interviews I did mentioned how surreal, how fantastical, how outlandish the stories were. But I didn’t think they were fantastical. I thought they were logical. I had my heart broken and thought, rather melodramatically, as you do when you’ve been dumped, “This hurts so much that I wish I could take out my heart and get a new one” – and so I wrote a story about hearts that could be rented and returned. When my merchant-navy boyfriend was away I got very lonely, and would develop these pseudo-relationships with other people, as sort of filler until my boyfriend got back – and that became a story about a lonely woman who makes a man out of paper. My dad was an alcoholic, and we never seemed to speak about it, and when we did speak about it the words never came out right – that was a story about a man who eats words. After his death the world seemed so dark and cold to me – that became a story about a grieving woman who eats light bulbs. It’s weird, and it makes perfect sense, but only from a distance, looking back. The weirdness and messiness of my emotions only formed into logical narratives when I could observe them, coldly and cleanly, from afar.

As anyone who does anything creative knows, it rarely makes sense at the time. It’s a process of stumbling in the dark, knocking flints together to make sparks, until finally the flame catches and the whole is visible. So too with life.

“A story can have only one true ending.”

Whatever choices we make, when we look back it will be easy to trace the path of it. How obvious it seems now – but it was never obvious at the time.

We’re all living a story right now, but we don’t know what it is. When it comes to life, we’re all long-sighted: we need distance to see clearly.

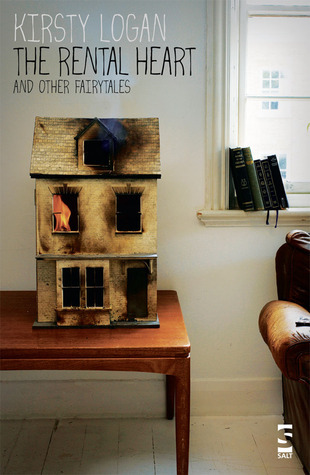

Review by Kirsty Logan.

Kirsty Logan’s fantastical fiction has thrilled me for nearly four years now, and I’ve been lucky enough to work with her hereandelsewhere online, but my favorite experience (so far) has been reading her debut story collection, The Rental Heart and Other Fairytales. These twenty surreal and sumptuous stories defy tidy labels. Fairy tales, magical realism, steampunk, literary fiction. It’s all there.

Logan’s work is humming with dreamy, erotic energy. Every detail, even the mundane, is scandalously compelling. Her characters are far from meek damsels and hollow princes–they are adventurers; positively lusty with their desire to discover what fate has in store for them. Witches, coin-operated boys, Eros-soaked lovers, an imprisoned empress, a girl with antlers, a boy with a tiger’s tail. Many of them are at liminal stages in their lives, in the twilight of adolescence or facing a major personal upheaval. Some of them live within traditional fairy tale retellings, and some of them live in their own contemporary fables, but every one of them is stuffed with lust and loss. They all seek love or a worthy substitution, and from Logan’s dark, wild worlds, they will haunt you.

1) First of all, when and how did you find out that Salt wanted to publish The Rental Heart?

It was an unexpected tweet. I have my phone set to flash up Twitter messages and Facebook comments but not new emails, and as I was getting ready to go out with my girlfriend Annie one afternoon I noticed a Twitter message flash up: CONGRATULATIONS. I had no idea what I was being congratulated on (though it’s always nice to be congratulated, no matter what it’s for). So I checked my email, and there was a lovely message from Salt saying I had won the Scott Prize and they were going to publish my book. Annie and I jumped around the room for a bit going WOOHOOOOO, and then we went out for a coffee. It was a good day, though really it was just the first step in a long process. I know in films there’s always The Moment where they get The Phone Call and then Everything Changes. But that made me realise that in life it doesn’t go that way. Book publishing is generally a slow and staggered process, and there’s not one big explodey moment where you’re showered with glitter and praise.

But as often happens in life, what I thought I knew turned out to be wrong, because for my next book I did get The Phone Call and The Moment! I was in a cafe and my agent called – the cafe was noisy and she was in a car with her baby in the back, so it was all rather loud and I knew I’d misheard her when she said ‘We’ve got an offer, are you sitting down?' It was only two days since she’d sent out the manuscript so I knew I’d misheard, as it takes months for editors to even glance at your manuscript. But no, it was true, and the offer was so fast and so amazing that I was glad that I’d been sitting down because if not I’d have fallen over. Now I try and live by a Dutch proverb: “Don’t worry. It will happen differently anyway”. Publishing, like life, often surprises you.

When I got home, I flipped through my writing notebook and found a note I’d written to myself months ago – lady lifts servants’ skirts. I have no idea what I meant, but I thought it fit nicely with the painting. A story can’t be about one character – what the lady needed was a love interest. I searched through online archives of paintings and found this one of a farmer-girl gazing dreamily into the distance. Aha!, I thought, this is the sort of girl who would run away on adventures.

So I wrote a story about a lady who lifts her servants’ skirts, and about the sorts of girl who ran away on adventures. One weird thing was that my first thought on seeing ‘Portrait of Guus Preitinger’ was “hey, she reminds me of PJ Harvey.” And when I went down to Bridport, a little seaside town in England, to collect a prize that 'Underskirts’ won – who was there at the ceremony but… PJ Harvey.

3) Which story was the most difficult to write and why?

They were all easy, and they were all ridiculously hard. Ideas are simple and plentiful – I have more story ideas right now than I could write for the next ten years, and every day another one appears. I don’t struggle to create worlds or situations, or to put sentences together. But there is one thing that I find near-impossible, and struggle with on every story I write: the 80% mark. I don’t know what it is, but something happens when I’m about 80% through a story when I just… stall. I’m frustrated, I’m bored, I know how to finish the story but I just can’t do it. I have to really push myself through. It helps to talk it out with other people, to take a break, or sometimes to just put my arse in the chair and my hands on the keyboard and just write the bloody thing. It never gets easier.

If I had to choose one, though, it’s 'Bibliophagy.’ For years I’d avoided writing about my dad’s alcoholism, for so many reasons: because I loved him, because I didn’t want to hurt him, because I didn’t want people to think that he was an alcoholic and nothing more, and because it hurt me too. I find that the best way to approach difficult truths is not head-on, but sideways, through the medium of myth. I couldn’t write about an alcoholic, but I could write about a man addicted to eating words, even though he knew that his addiction was tearing apart his already fractured family. That was tough to write, though I’m glad I did it. Honesty hurts, but writing falsely safe stories is no good for the writer or the reader.

Even when I write stories that aren’t set in the present, they’re rarely historical in the strict sense – I’m sure a historian would shred them to pieces! I often write in 'fairy tale time’: a vague past, a once-upon-a-time that might not be historically real but is real in a timeless sociological and emotional way.

5) Speaking of settings, how important is your upbringing and current life in Scotland to your literary aesthetic?

Scotland is so inspirational to me. Although I’m Scottish by family, I was actually born in a small town in the English Midlands, and it was dull dull dull. Both my parents are from Scotland, and my family moved back to Glasgow when I was 13. If I’d stayed in that English town I certainly wouldn’t be the same writer I am today.

My dad was also a big influence on me, and I’ve always associated him with water and the sea. He was born on the small Scottish island of Bute. When I was a child he had a small sailboat called First Symphony on Lake Windermere in England, and used to take me out sailing. After he died, my mother and brother and I scattered his ashes on the beach at Culzean Castle, which looks out on Bute. Now every time I’m by the sea, I feel that I’m with my dad.

I’m currently working on my third book, a collection of linked stories called A Portable Shelter. It’s inspired by Scottish and Scandinavian folk tales. Part of the research for the book is to travel around the Scottish Highlands and Islands, and I did the first part of that recently when my girlfriend Annie and I went up to the Applecross peninsula with our lurcher puppy Rosie. The landscape there is glorious, whether it’s endless blue skies or torrential rain (and we got a bit of both!). I ate local squat lobster, went out on a fishing boat, explored lochs, and climbed seaweed-slippery rocks. I even stripped to my knickers and waded into a loch to retrieve Rosie’s ball when I threw it in deep water. And it was a particularly memorable trip because Annie and I got engaged. So many of my memories are linked to Scottish landscapes.

Photo by Luis del Rio.

6) What are your favorite fairy tale retellings?

I’m madly in love with Emma Donoghue’s Kissing the Witch. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on retold fairytales, and to my mind Donoghue’s was the only book that actually subverted fairytales at their base level, rather than just changing a few details or flipping characters around. It’s sadly out of print now, but if you can find a copy then grab it. Reading it is an education.

Conversation by Dawn WestandKirsty Logan.

There are not two sides to every story. There are as many sides as there are people involved – and most situations involve far more than two people. There is no such thing as an objective truth, because everything we see and hear and know has to be filtered through us. And if it’s filtered through us, does that mean it’s a part of us? Do we own it? Are the things that happen to us ours to tell – no matter who else is involved?

“Skinner wants a report in one hour. What are you going to tell him?”

“What do you mean what am I gonna tell him? I’m gonna tell him exactly what I saw. What are you gonna tell him?”

“I’ll tell him exactly what I saw.”

“Now, how is that different?”

‘Bad Blood’ is a major fan favourite (even Gillian Anderson named it as one of her faves), and for good reason. It’s funny, fast-paced, and has some major tension between Mulder and Scully. Plot-wise, it’s about the agents investigating vampires in Texas. Mulder thinks he’s found the monster and stakes him through the heart, only to find – oh no! – his vampire fangs are plastic. But then – oh yes!/oh no! – it turns out the whole town is populated by vampires. Good luck explaining that to Skinner, agents.

Structure-wise, it gets a bit more interesting. The episode is told in flashback by both agents in turn, with each contradiction shown in glorious detail. In Scully’s version she’s calm and hardworking, Mulder is exuberant and gullible, and the local sheriff is sexy and charming. In Mulder’s version he’s polite and sceptical, Scully is whiny and dismissive, and the sheriff is a buck-toothed bumpkin. Neither of these tellings can be true, because they contradict one another. But both tellings are true, because it’s the truth as they remember it.

The camera makes us think there is an objective version of the truth, because there it is, unfiltered, right in front of our eyes. But in life there is no camera lens, and there is no objective truth. We can’t get outside our own brains into unfiltered reality. There is no world 'out there’; there is only the one we see – and the worlds that everyone else sees, each one slightly different, none wrong or right.

In watching 'Bad Blood’ we, the viewer, know that the truth lies somewhere between Mulder’s and Scully’s versions of events. Without even thinking about it, we construct a version of truth that merges both stories. We can do this because both agents get to tell their version of events. But in life, not everyone gets to have their say.

“It’s obviously not a vampire.”

“Why not?”

“Because they don’t exist?”

“Well, that’s one opinion and I respect that.”

I am a writer, and I write about my life. I’ve written about my body, and the things I’ve done to it, and the things that other people have done to it. I’ve written about the people I’ve left and the people who left me. I’ve written about my irritating, handsome, intelligent, frustrating younger brother. I’ve written about my mother and how terrified I am of her inevitable ageing. I’ve written about my complex relationship with my alcoholic, troubled, always-loving father. I’ve told my truth as I knew it – but it’s my truth, and only mine.

My father did not write. My mother and brother do not write. Everyone I’ve ever had a relationship with does not write. They don’t write, and they don’t tell their stories. The only version of truth that exists in the world is the one that I have written.

And I try to tell the truth, I really do, but my truth is not the same as anyone else’s. I won’t even pretend that my stories are an attempt at objectivity, because in these situations it doesn’t exist. What’s the objective truth of why a couple breaks up? What’s the objective truth of how my father and I loved and resented one another?

If something happens to us, I think we have the right to tell it as we remember it. We all have a truth – but no story happens to us alone. And our truths can hurt.

“Where’s your proof?”

“You’re my proof! You were there!”

I write my stories because they belong to me, and I don’t care who else was involved. If my story of a break-up hurts the other person, then that’s just tough luck for them. I believe that if we don’t want our actions made public, then we shouldn’t do those actions. The other people involved are free to write their own versions if they want to, and it’s not my fault that they don’t.

That’s hard for me to write, even though it’s what I believe. Written down, it looks so cruel. I am a mean and selfish writer, telling my stories, trampling all over my loved ones’ feelings, all for the hope of a moment of connection with an unknown reader. And perhaps this whole essay is my attempt to justify my selfishness – to justify the selfishness of every person who tells their truth. If we were to only tell stories that didn’t hurt anyone’s feelings, no stories would be told at all.

I wish I had answers. I wish there was a clear morality when it came to telling our stories. But much like watching the best X-Files episodes, I’m only left with more questions.

Review by Kirsty Logan.

“Why don’t I have a desk?”

“Okay, so we’ll have them send down another desk and there won’t be any room to move around her but we can put them really close together face to face, maybe we can play some Battleship.”

‘Never Again’, like all the best X-Files episodes, is both Scully-centric and intensely thoughtful. It begins with Scully wandering away from Mulder’s interrogation of a witness to a Vietnam War memorial, where she finds a faded rose petal. Life, we’re reminded, is brief. Scully is now in her 30s, and her dreams of a husband, child and conventional life seem to be fading with each passing year caught up in Mulder’s grand scheme of weirdness. As she points out, despite being a high-powered FBI agent she doesn’t even have her own desk.

So when Mulder is forced to take a holiday, Scully uses the time alone to go in search of the truth. But this time, she’s searching for the truth about herself. And she starts by getting a tattoo.

“Tattoo hurt at all?”

“It feels weird. I can’t see it, but I feel different.”

I have five tattoos. I got one every two years between the ages of 16 and 24. I meant to carry that on for the rest of my life, but when I turned 26 I realised I wasn’t ready for another. So I put it off, and I put it off, and I put it off. Now I’m 29 – almost 30 – and I don’t know if or when I’ll ever get another tattoo. I have other ways now of expressing myself, of reminding myself, of marking the stages of my life.

Each tattoo marks my need at a particular age. Wings on my back at 18, in the long and messy summer between school and university, to show that I was going to escape from the rain-damp streets of Glasgow. Four tiny parallel lines on my ribs at 20, for the partner and two children I wanted. A semicolon on my toe at 22, to show that although I had graduated university it was just a break in my learning, not an end. A burning heart on my left wrist and a book on my right wrist at 24, when I was a waitress and struggling writer, to remind me that if my daily worries weren’t about love or literature then they weren’t worth the worry.

Most of these reminders remain just that: good-luck totems for unneeded dreams. I don’t need wings, because I no longer feel the need to escape this city. I don’t need the book or burning heart, because my personal and professional lives now focus entirely on books and love.

But I don’t regret my ink. I don’t want to forget or deny the person I used to be. The thing about having a tattooed body is that you can never forget who you were.

“I feel like I’ve lost sight of myself, Mulder.”

The Dana Scully we see in 'Never Again’ both is and isn’t the Scully we know. Often she’s portrayed as an idealised mother/lover figure, the perfectly intellectual woman whose brain is as beautiful as her body – the former of which she uses a lot more than the latter. Here, she’s impulsive and knowingly reckless. She’s still smart, and she’s still sexy, but she’s more. She’s human.

This Scully gets drunk and hooks up with a stranger even though she knows he’s trouble. He tries to kill her because his tattoo, voiced by Jodie Foster, is terribly jealous (this is the X-Files, remember). But then it’s over, and the next day Scully wakes up and goes on with her life. She doesn’t need to deny the drunk-hookup part of herself, so she carries it with her: not just in her memory, but on her skin.

Tattoos remind us of who we were. But who you were then is not necessarily the same as who you are now.

We all change, every single day, and when we look back at ourselves two or five or ten years ago, we’re strangers. Some people can manage that: can carry the noisy multitudes of their past selves inside the fragile shell of their current identities. But some can’t, or won’t.

If you’re the type to burn old journals, throw away love letters from exes, to deny the you of yesterday – then don’t get a tattoo. It’s a journal on your skin, and you’ll never really burn it.

“All this, because I didn’t get you a desk?”

“Not everything is about you, Mulder. This is my life.”

“Yes, but it's…”

'Never Again’ begins with Scully feeling unsteady with her place in life, wanting the grounding force of a desk, something that’s hers alone. By the end, she still doesn’t have a desk, and she still isn’t steady – but she’s a step closer. Unusually for the X-Files, the dialogue doesn’t end, it just tails off. The conversation remains unfinished: a partial, grasping reach towards meaning that never quite lands.

A tattooed body, too, remains always unfinished. However many mementoes and reminders we ink onto our skin, there will always be more. Tomorrow we will change again. The years will pass and those past versions will become strangers. Why did we make those choices? Why did we do/say/leave/buy/eat/fuck what we did? We’d never decide it that way now. We’d never do those things now. But we did it then, and if we were back there, we’d do it again. The future you is just as much of a stranger as the past you.

It’s up to us whether we deny those complex, mysterious previous selves – or carry them with us, in our minds and on our bodies.

Review by Kirsty Logan.

When I was 17, I was obsessed with my best friend. I loved her open-heartedly and possessively, the way only a 17 year-old can love.

It is a feeling familiar to any teenage girl who has been in platonic love with another teenage girl. Together you create a tiny, obsessive world: in-jokes, coded words, frantically loving bands and films and books because they’re meant for you, they’re speaking to you – and not just you, singular, because there is no you, singular any more; there is only Us, Me and You, the pair of us so bright and vivid and glitteringly perfect that everyone else in the world feels like a grey shadow miming inanities.

My love for her was glorious – and then it wasn’t. She helped me see that you can’t obsessively love someone without obsessively hating them too.

“We are but visitors, hurtling through time and space at 66,000 miles an hour. Tethered to a burning sphere by an invisible force in an unfathomable universe. This most of us take for granted, while refusing to believe these forces have any more effect on us than a butterfly beating its wings halfway around the world. Or that two girls, born on the same day, at the same time and the same place, might not find themselves the unfortunate focus of similar unseen forces. Converging like the planets themselves, into burning pinpoints of cosmic energy, whose absolute gravity would threaten to swallow and consume everything in its path.”

In ‘Syzygy’, Scully and Mulder are called to the town of Comity to investigate the mysterious deaths of high-school boys, for which the townspeople blame a satanic cult. The agents soon notice that all the murderous happenings seem to involve two teenage girls, Margi and Terri. The deaths, clearly, are grabbing everyone’s attention – but look beneath the surface and everyone in the town is acting a little crazy. Mulder and Scully are caricatures of themselves: Mulder flirtatious and coldly sarcastic, getting tipsy on vodka in his hotel room; Scully irritable and jealous, stalking the corridors and sucking on a cigarette.

As the town astrologer points out, it’s all about the planets. It’s horoscopes and astral alignments and doomed birthdates, but at the heart of it is this: only the bright burn of teenage girls’ passion is intense enough to make a town implode.

“Hate her, wouldn’t want to date her.”

My best friend was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen. I wanted to be her, and I wanted to have her. I wanted to fold her up tiny and keep her in my pocket forever.

She was small-boned and fine-haired with a row of silver rings up the ridge of her right ear. She ate only toasted white pitta bread with butter. She fell asleep every night to Silverchair’s Frogstomp. She spoke Portuguese after three years in Brazil with her missionary stepfather, who hit her mother and walked with a stick. Although I spent entire weekends in her house, I don’t remember ever meeting her mother; I don’t know what she did for a living or why she spent so much time out of the house or who cooked my best friend’s meals – if, indeed, anyone did. Considering the depths of my obsession, I knew very little about her. I clung to the small details of her as if they meant something.

She didn’t love me back, but it almost seemed like she did. We couldn’t be together but we couldn’t be apart, so we worked through a cycle of declarations and stay-close rejections that left me alternately ecstatic and despairing. Once she told me she was going on holiday for a week, and I genuinely could not imagine an entire seven days away from her. How would I fill the hours? What was the point of waking up? How would I breathe without her?

Even at the time, I would have been hard-pressed to explain just what it was I liked about her. She was self-absorbed, manipulative and dull. But still I loved her.

And honestly, I hated her. She went out with the guy I liked, even though she knew I liked him – possibly only because I liked him. She was prettier than me and thinner than me, and she made sure I knew it. She didn’t want me to have anything that she couldn’t have, or do anything that didn’t focus on her. We would happily have torn one another’s eyes out, and then built walls around the two of us to keep everyone else out.

We were awful to one another because we both allowed it. Together we obsessed a world into creation, our days stitched together with jealousy and need.

Oh, how I loved her. Oh, how I hated her.

“I’m driving. Why do you always have to drive? Because you’re the guy? Because you’re the big, macho man?”

“No. I was just never sure your little feet could reach the pedals.”

Margi and Terri aren’t the only ones in 'Syzygy’ with a claustrophobic friendship. Mulder and Scully’s world is constantly spinning with conspiracies and monsters and black oil seeping from people’s eyes – but the only constant, the still point in a hectic world, is their relationship.

As a fan, I love the episodes where the agents act out of character: Season 4’s 'Never Again’, where Scully has a one night stand with a murderous tattooed man; Season 5’s 'Bad Blood’, where the story is told from each agents’ perspective, Mulder’s version showing Scully gooey-eyed and stroppy, Scully’s version showing Mulder gullible and demanding; Season 6’s 'Arcadia’, where Mulder and Scully go undercover as suburban married couple Rob and Laura Petrie, complete with conjugal bickering and unfortunate nightwear. And then there’s 'Syzygy’, in which the agents bicker and bite and make snippy comments about one another’s belief in the paranormal.

Do Mulder and Scully hate each other as much as they love one another? It makes sense. Scully should hate Mulder: before she met him, her career was blossoming; now she’s so firmly entrenched in that basement office that she can never leave. And Mulder should hate Scully: without her, he would be free to run straight into the danger where the truth lies; with her, he has a reason to hold himself back.

We tell ourselves that Mulder and Scully’s snipping and sniping is caused by the influence of the cosmos, and not the build-up of long-suppressed grudges. But it’s not as simple as that. The episodes that exaggerate their characters work because we know that there’s a spark of truth.

It’s only the third season, but already the agents’ world has shrunk to just the pair of them. Who else could ever understand all the things they’ve seen? What would be the point of either of them carrying on the X-Files alone? How could they breathe without one another?

“Happy birthday, bitch!”

Slowly but surely, the walls of our world started to fall. She got a boyfriend – a scrawny, adorable, Kurt Cobain-esque scrap of a boy. I got a girlfriend – a pussycat-sweet girl who was as obsessed with me as I was with my best friend. We both left school. I heard she got pregnant and took out all her piercings and got a job for an insurance company.

That should be the end of the story, but there’s a postscript. Years later, I bumped into her at a rock show. I smiled awkwardly and said hi, and she punched me in the jaw. I still don’t know why. It was the first and (so far) last time anyone has ever hit me.

I loved her, and I hated her, and all of it faded to nothing. Finally, at that rock show, she love-hated me enough to want to hurt me. But by then, I didn’t feel anything for her at all.

Review by Kirsty Logan.

DJL loves it when she discovers a new linocut artist. Here are Liz Myhill’s illustrations for Kirsty Logan’s A Portable Shelter.

Post link