#korean cinema

Cho Yeo Jeong by Bong Joon Ho

The Row S/S 2020

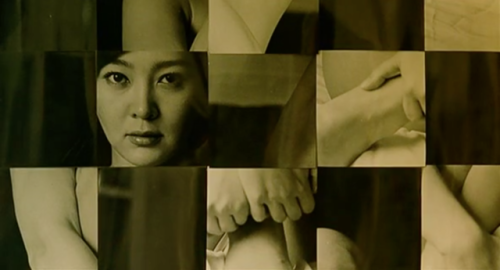

A shot directly inspired by Bong’s Mother (2009)

Post link

Just over here crying about a zombie movie.

Cinematography Appreciation

Castaway on the Moon (2009) | DOP Kim Byeong-seo

I put on the last 1000 on my pedometer.

It’s not for health reasons.

After putting on 10,000 steps, I feel like I had a good, busy day.

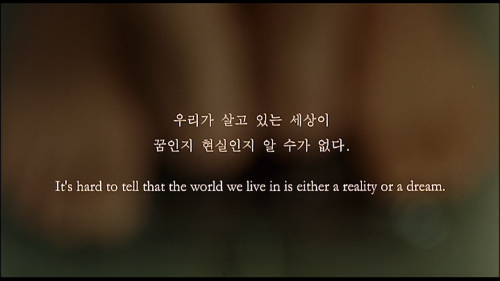

Castaway on the Moon (2009)

So bored. Nothing else like it. The perfect boredom.

Castaway on the Moon (2009)

Castaway on the Moon (2009)

Director & Writer Lee Hae-jun

DECISION TO LEAVE / 헤어질 결심 (2022) dir. Park Chan-wook

DECISION TO LEAVE / 헤어질 결심 (2022) dir. Park Chan-Wook

괴물 (The Host) // dir. Bong Joon-ho (2006)

a fallen pilot from the american allied forces, two south korean escaped soldiers, and three north korean guerrilla soldiers coincidentally meet in a secluded village called dongmakgol, where its villagers have never seen a gun or heard of the ongoing korean war - what could possibly happen?

what takes place in the next 2 hours of screentime is a lovely mix of comedy, drama, wartime violence, nostalgia, and heartwarming relationships that makes welcome to dongmakgol one of the better reunification films i’ve seen thus far.

what really distinguishes welcome to dongmakgol from other war films, though, apart from the creation of dongmakgol itself, is the injection of absurd comedic moments (as the koreans might say, gags) that had me chuckling in my seat. those who watched the film would know - from the explosion of popcorn to the guerrilla soldiers wasting their ammunition on killing snakes - and in some way this resembles bong’s trademark casual juxtaposition of comedic moments and grave topics. yet what welcome to dongmakgol did not neglect to do was to emphasise the severe trauma war could cause soldiers, regardless of which side of the fence they stood on. to this, i found the ensemble acting so solid i felt for every character, even the unnamed villagers. it was also a pleasure to see young jung jae-young (!!), shin ha-kyun, and kang hye-jung.

its ending, where the north and korean soldiers leave dongmakgol to create a decoy base to prevent the american forces from bombing the village, definitely brought a tear to my eye. as did the departure scene, where the dongmakgol villagers - not knowing the magnitude of the soldiers’ sacrifice - weep goodbye to the strangers they had sincerely welcomed and taken care of. ultimately, i think welcome to dongmakgol is at heart a pacifist film, with dongmakgol representing a pre-war simplicity and innocence that both sides (and the director) yearn for.

(i was surprised by how explicitly anti-american certain scenes were, especially in depicting american soldiers’ disregard towards bombing potential communist bases, despite risking civilian lives. interestingly, this film was released around the same time as the host - and forms part of the anti-american zeitgeist of the early 2000s, while shedding light on foreign forces’ brutality during the war.)

tonally,welcome to dongmakgol reminded me of studio ghibli films, notably grave of the fireflies. this was achieved most ostensibly through joe hisashi’s music, which create a surreal and mystical atmosphere for the village. the stone figures / masks that decorate the paths leading to dongmakgol, or the appearance of butterflies whenever wartime weapons threaten to disrupt dongmakgol’s peace further emphasised the simplicity of dongmakgol and its connection with nature. the replacement of the symbols of wartime brutality with symbols of nature was a genius move - even the depiction of american bombs resembled fireworks.

welcome to dongmakgol, all the while placing the severity of war square centre, uses its artistic license to create an extraordinary, light-hearted tale of the korean war. it may seem like a cluttered film from afar, but it’s a surprisingly easy film to like and feel for. – 9/10

lee chang dong parades his literary roots in burning, which blends murakami’s barn burning and faulkner’s barn burning to create a wholeheartedly korean tour de force. absolutely insane.

the film starts off with an unemployed and hapless jeong-soo (yoo ah-in), who is working side jobs to make ends meet but dreams of being a novel writer. he meets his paju childhood friend hye-mi (jeon jong seo makes her grand debut), who is a free-spirit compelled by a “greater hunger” for self-actualisation and fulfilment in life. jeong-soo and hye-mi begin an intimate relationship, which comes under threat when hye-mi returns from a trip to africa with her new friend ben (steven yeun). ben, with his wealth and generous personality, seems better able to materially and emotionally provide for hye-mi than jeong-soo, who stays in a humble farm and is often caught off guard by her unusual behaviour.

but the film maintains a veiled sense of danger around ben and his apparent perfection, which is verified at the halfway mark, when ben reveals to jeong-soo his arsonist hobby of burning barns (or in this case - to localise to rural korea - greenhouses). ben lets in to jeong-soo that he burns barns once every two months, “a good pace”, and he’s decided that he would burn a barn near to jeong-soo very, very soon. jeong-soo, while also trying to find a vanished hye-mi, obsessively checks on the barns near him but even after a month no barns seem to be burning or have burned. when questioned, ben enigmatically advises jeong-soo that “sometimes you don’t see the barns that are closest to you”, and states that he had indeed burnt the barn 1 or 2 days after they last met, coinciding with the date of hye-mi’s disappearance.

jeong-soo begins to suspect that ben’s “barns” are not real barns, and his suspicions are further confirmed when he finds hye-mi’s watch in a drawer of random women’s accessories and hye-mi’s cat in ben’s apartment. luring ben to paju, jeong-soo stabs him with a knife, dumps his body in his porsche, douses the car in fuel, and sets it on fire.

the film is devoted in its adherence to murakami’s plot, but builds its characters with reference to faulkner and fitzgerald. jeong-soo’s character is constructed from both murakami’s and faulkner’s barn burning’s; his socioeconomic background and relationship with his father models faulkner’s protagonist’s, while aspiring to be the successful writer in murakami’s. ben’s character embodies the wealth of murakami’s accomplished protagonist with the dandy behaviour of fitzgerald’s gatsby. i found yoo’s performance as the insecure and genuine jeong-soo very stable and confident, and was surprised by steven yeun’s effortless transition into korean cinema. jeon jong-seo, who naturally possesses an air of mystery and lackadaisical rumination, must have made such a splash into chungmuro with this debut performance as well.

i really liked that lee chang dong, while creating the mix of characters across literary works, had managed to weave in a subtle but heavy critique of class inequality. lee makes clear to us that ben’s and jeong-soo’s worlds are clearly different - ben’s porsche in the fields of paju is as incongruous as jeong-soo’s white lorry in the hills of gangnam. ben’s generosity to jeong-soo and hyemi is also always twinged with a condescension that only the rich can afford.

ben’s insincere treatment to the poor is most obvious in his choice and treatment of his muses. his muses are always from lower socioeconomic backgrounds - hyemi worked parttime as a hostess at a shop event, and his next muse works as an assistant at a duty-free store that caters to chinese tourists. and he parades his muses in front of his circle of well-off friends, who goads hyemi to demonstrate the african “greater hunger” dance and encourages his next muse to talk about her disregard towards chinese tourists. the friends’ expressions belie holier-than-thou attitudes that mock the girls’ self-perceived worldliness, resting in the comfort of their gangnam homes that they would never need to encounter african salvation or chinese tourists. i found the echoing of these scenes (hyemi & his next muse) really effective - it hit home how deeply entrenched class divide is, beyond the superficial niceties exchanged between the rich and the poor. if parasite was a movie that delivered an absurdist criticism of class inequality, burning is a film that packs a subtle, realistic, and equal punch.

what i felt was a slight weakness to the film was the lack of development of hye-mi’s character. hye-mi’s character is a familiar one - the manic pixie girl whose gripes with life effortlessly charm the men she meets - and her easy servitude to ben was slightly off-putting. but her role, i guess, was a plot device meant to draw out larger themes in the film (e.g. hyemi is just one of the many poor girls that the rich play with, just as “there are many barns in korea’s countryside). more importantly, hye-mi’s unreliable character and her pantomime hobby - which bridges the real and the imagined, the present and the absent - weaves together themes of questioned memory and loss. is the tangerine real? does her cat exist? was there a well, and if yes did she fall into it? where.. is she?

as the film ends with jeong-soo’s gruesome act, we are reminded of hye-mi’s words at the beginning. she mimes peeling a tangerine to jeong-soo, who praises her. “you know why i am so good at it? the trick is to not think about whether the tangerine is present or not, but to not think about the tangerine at all.” – 9.5/10

poetry closely follows the life of Mi-ja (portrayed by Yoon Jeong-hee), who raises her only grandson who is in high-school. leading a humble life, she earns a partial income by cleaning for a well-off old man who had suffered from a stroke, and goes to poetry class after being diagnosed with alzheimer’s. there are 2 main plot lines in poetry - that of Mi-ja re-encountering poetry and reconnecting with her thoughts and the words that have seemed to slip by, and that of the sexual assault conducted by her grandson and his friends on their classmate, resulting in the classmate’s suicide.

i watched the film anticipating only the first plot line, expecting a bittersweet reflection of an old lady’s life reignited through poetry, and the beautiful flowering of a new phase of life enabled by poetry. but while the 2 plotlines were kept relatively distinct throughout the film, we observe how the former provides Mi-ja with an escape and coping mechanism to deal with the gravity of the latter. for instance, encouraged by her poetry tutor to really observe the world around her, Mi-ja gets carried away when talking to the victim’s mother about the countryside’s sweet tangerines and pleasant weather. in another scene, a burly man from her poetry reading club (who turns out to be a policeman) arrives as Mi-ja plays badminton with her grandson in the neighbourhood alley. acting as if there was no gravity moment happening in the background, Mi-ja nonchalantly continues playing badminton with the poetry-reading policeman, as her grandson is taken away in a policecar behind her. she is literally sustained by her engagement with poetry.

but the most significant convergence of the 2 plotlines is the ending. having struggled both with her consciousness as a poet and her conscience as the guardian of a rapist, Mi-ja finally arrives at an internal peace and disappears. against a beautifully arranged series of stills of the neighbourhood places that Mi-ja used to occupy, she narrates the poem that she finally put together. but the victim soon takes over the narration, as the scenes slowly trace the victim’s last day and end with the victim standing over the bridge, right before she jumps into the river. the trauma had provided Mi-ja with the impetus to become a “true poet”, but poetry had also helped her to articulate - and come to terms with - the complicated feelings that she had repressed about her grandson’s sins. just as how the film opened, where an extended shot of the stream’s gradual waves revealed the victim’s dead body, the film ends with an extended shot of the same stream’s waves.

being released a year after Bong’s Mother (and Yoon Jeong-hee winning the same best actress award that Kim Hye-ja did), and both being character studies of old poor women who are protective guardians of dismembered males, it is inevitable that the films draws some comparisons. while Kim Hye-ja’s character veered into histrionics at times, i found Yoon’s character to have been more charitably shaped in that she is given more nuance, conflict, depth, and room to develop. when her son is accused of sexual murder, Kim’s character plunges into a wholehearted self-delusional defence (only to be crushed at the realisation of the truth and her complicity in it). in comparison, Yoon’s character begins with self-denial, inaction, action, empathy with the victim, and finally personal resolution. the stories are slightly different that way - Mother brings light to the dangers of overwrought oedipal impulses that can ultimately incapacitate, while Poetry deprioritises the relationship between grandson and grandmother for the self-actualising relationship Mi-ja develops with herself.

while Mi-ja’s character frustrated me at times, particularly the way she carried herself, i enjoyed the side of her that deeply empathised with the victim. when Mi-ja has sex with the handicapped old man with a stony face and later asks him for money, she is subconsciously comparing her situation with the victim’s, realising that women usually only have an illusion of choice when dealing with men’s sexual devices. when Mi-ja remembers her childhood hopes of being a poet, she is drawing on these long-ago memories while mourning for the victim’s own early end of hopes and dreams.

this is my first film by lee chang dong, and i’m happy to say that i enjoyed the mood and tone of the film. either plotline had the potential to meander and explode into melodramatic territory, but the plotlines diverged and intertwined with such control, and the film always treated Mi-ja with a certain detachedness and delicate subtlety. i find myself more seriously moved by films that appear to not have much action appearing in them; the ability to pack waves of poignant revelations into minimal actions is a level of subtle story-telling that i really appreciate. – 8/10

how do you judge a film that centres around a modern historical event & biopic, written for a patriotic domestic audience whose minds are still afresh with emotions of the era?

song kang-ho plays enterprising tax-turned-human rights lawyer sung woo-suk, who is not so discreetly modelled after roh moo hyun, who was also involved in the 1987 uprisings against korea’s then-authoritarian rule and later became the president of korea. the film takes place in 1981, when the spectre of the 1980 gwangju uprising looms large in everyone’s minds. for historical context, the 1980s was a dark period in korea’s history, when korea was ruled by a series of authoritarian and heavy-handed presidents. the images of 1980 gwangju often remind people of tiananmen.

having been treated kindly by an ahjumae who sells gukbapwhen he was a poor construction worker studying to become a lawyer, song sacrifices his lucrative career to defend her son and university students, who have been arrested on the counts of studying contraband literature that promotes socialist unrest. in a plot that closely narrates reality, song sets out to prove the innocence of these university students and expose the inhumane torture methods employed by the police to extract confessions.

there is little room to comment on the plot itself, given that the film is so tightly tethered to historical events (in the same way that i am frustrated by the plot in juror 8). often i find that historical films get more creative leniency when remaking events that happen generations ago (say the age of shadows), or are based on unique strands (a taxi driver). but this film is so wholeheartedly patriotic and historical, that it loses nuance and self-awareness. in an impassioned exchange, the villainous cop instructs song that this is a case of national security, and the law does not apply to national security cases. the camera then closes up on song - “who decides what cases are of national security? you said the country? who constitutes the country? according to the constitution, the country is its people & their freedoms!” tell me this is not a clear appeal to the audience’s patriotism (don’t get me wrong, i actually liked this scene the most.. song’s acting brought tears to my eyes! it’s just in your face)

at 2h 17m, the film lags and drags on at certain moments too. a lot of background-setting around roh/sung, and plenty of police brutality scenes. when you know that there are no surprises round the corner, the scenes become slightly self indulgent.

and when historical films like these are made, characterisation is often sacrificed. song tried to imbibe his character with as much depth as possible (the everyman rockstar overcoming inner turmoil with a strong moral compass), and im si-wan did a deft job at portraying the emaciated soulless student. but those familiar with korean history will also know that roh, although very much celebrated as a folk hero through sung, committed suicide in 2009 after intense bribery allegations. given a somewhat divided national memory of roh, this film is uncomfortably generous in its praise and commemoration of his activist legacy. it is fine to celebrate his deeds independently of what he did before or after, but to do so without nuance is slightly irresponsible film-making.

ironically, what i got most out of the film was a critical appreciation of historiography and historical memory in film-making. being a trained historian, seeing e.h. carr’s what is history? accused of instigating fascism provoked a lot of thinking. on one hand, the above is criticism of the film, but on the other, it is a demonstration of how engaged i am with the film’s material. i think there are better films about 1980s korea, but here is a decent one if you need a nationalistic jolt. – 6/10

truth is, this was never going to be a genuine oscars foreign film contender (korea’s nomination should’ve been the handmaiden).the age of shadows is a move that delivers on execution but not plot. plot-wise it checks every trick that a double-agent movie could possibly possess, in five acts.

act i- seoul (or gyeongseong / keijo to be more accurate, which was seoul’s name during the japanese occupation). a group of korean rebels are out to import bombs from shanghai to resist japan’s occupation of korea in the 1920s, and two cops with the japanese forces (a deftly assuring Song Kang-ho plays the morally conflicted protagonist, and a scene-stealing Uhm Tae-goo plays the quick-to-anger, caricatured japanese) are tasked to arrest them alive. the cops make contact with the rebels (right hand man Gong Yoo), and the rebels take off to shanghai.

act ii- shanghai, republican china. Song is persuaded by Gongand his boss, leader of the rebel forces (played by Lee Byung-heon, who possibly is the only chungmuro star whose cinematic weight could convince viewers that he outranks SongandGong) to deceive the japanese police to buy the rebels time to export the bombs. Song remindsGong that “I cannot guarantee what form I’ll be in, the next time we meet”.

act iii- shanghai express train, and by far, the best act of the film. it is revealed that the rebels’ have a mole in their team, and SongandGong team up to out the mole (Shin Sung-rok).Song proves his loyalty to the rebels and kills Uhm, and parts with “The next time we meet, either I will be dead, you will be dead, or we will both be dead”. ok, we get it.

act iv- arrival back at seoul + bombs. the rebels are caught at the train station. who knew immigration checks could be so intense. Han Ji-min’s character, love interest to Gong’s, is captured and brutally tortured (her bloodcurling scream was genuinely memorable). Song is tasked to lure Gong in to prove his loyalty to the Japanese empire, and soothing lounge music is effectively deployed against objectively heart-wrenching scenes of Japanese forces capturing the other rebels. when asked by an ex-rebel, Songagrees to help Gong, but this turns out to be a trap by the Japanese forces, who had all along doubted Song’s allegiance because of his ethnicity.

act v- at trial, Song denounces his affiliation with the rebels and proclaims loyalty to the Japanese empire, and is acquitted. but this is all part of Gong’s plan, concocted upon realisation of the trap, when he begged Song to never admit his association with the rebels, so that Song could not let the other rebels’ sacrifice go to waste, continue the mission and bomb the japanese unit, which he did. i teared. we end with Lee’svoiceover (to a Korean patriot’s quote, i suspect), “we must step on the bodies that have sacrificed to stand closer to independence.” and Song, who is the only survivor of the attack, replies, “we must see each other again”

i especially enjoyed the film because i was familiar with the historical context and used to the anti-Japanese patriotic double-agent tropes that ever so often appears in korean / chinese films. and i suspect this is why international audiences may flounder slightly more with the convoluted side-switching in the film.

i really enjoyed the richness of the directing and cinematography. the shanghai express train act was very creative - the narrowness of the corridors emphasises the constraints of the rebels as they try to hide, but the lengthy expansiveness of the train itself allowed for the camera to whip back and forth to good storytelling effect. we follow the swivelling camera just as we follow in the confusion of Song,Gong, andUhm as they try to size each other up. i’ve never watched this director’s films before, but the good the bad the weird (affectionately called “nom nom nom” by locals) and i saw the devil have been on my list.

the weakness of the film is obvious. the cast, while pretty and undoubtedly capable, is imbalanced when put to use. Song practically carried the entire film, even patching up the gaps in the script and character development. Gong is charming but i personally think he has still a bit more to go before he becomes a truly charismatic chungmuro lead, in the same way that Song, Lee orYoo Ah-in are.Lee was technically a cameo, but his presence in the 3 extended cameo scenes was so important that it outshone Sung, who i thought was terribly underused in his role as a mole. i personally like Han as an actress a lot, and she pulled off her scenes brilliantly, but i related so little to her death because we had no real backstory.

regardless, once in a while you need a good espionage, double-agent, cat-and-mouse thriller, and the age of shadows delivers just that excellently. i think this is a slicker version of hong kong’s infernal affairs, and should be commended accordingly. –8.5/10

house of hummingbird is a coming-of-age tale of how an ordinary 14 year-old girl finds herself amidst the relationships she develops with the people around her. in doing so, the film draws on themes big and small, which effectively paints a scarred national psyche and depicts the struggles of normal people as they try to keep apace.

the film can be described as a quiet feminist criticism of gender inequality in a “modern” society. eun-hee and her good friend, ji-soo, are victims of domestic abuse by their older brothers, who have been conditioned by patriarchal notions that empower them to assault their sisters as a means of “reprimanding” them and keeping them in order. when eun-hee and ji-soo are caught for shop theft, ji-soo trembles at the fear of being hit by her brother back at home. when eun-hee bravely tells her parents over dinner, in the first third of the film, that her brother had hit her, her older sister gives her a glance. initially i thought the glance was a glance of surprise and reproach, as if to tell eun-hee to remain silent. but i later realise the glance meant that she herself was a victim of her brother’s abuse, and the glance was a pleasant surprise at her courage. the uncomfortable coexistence of domestic assault and women’s education empowerment (the daughters are enrolled for after-school tuition), points to how society’s claims of modernisation will always ring hollow if women cannot even have basic human rights.

the exhortations of gender inequality are constantly woven in the film. eun-hee’s mother knows that her father is having an extramarital affair, but never explicitly addresses it. nonchalantly asking eun-hee “what was your father wearing when he went out today?” and then checking his closet to see whether he wore his best suit out on a date, eun-hee’s mother is the film’s closest representation of the virtuous traditional asian wife. eun-hee almost walks in her mother’s footsteps - even after seeing her boyfriend flirt with her schoolmate, she takes him back immediately with little questioning. it is only with young-ji’s advice that she needs to not live her life passively that eun-hee starts to assert herself and retaliate. when eun-hee is caught for shoplifting, her father tells him he would rather the shopkeeper send eun-hee to the police station than send some rice cakes over as a “favour”. this is in contrast with her father’s treatment of her brother, offering him money to buy burgers to bribe his schoolmates to vote him as school president.

eun-hee’s relationship with yoo-ri, her junior at school, is less significant as an exploration of sexuality but rather an example of how eun-hee is desperately trying to find true companionship in the people around her. contrasting her friendship with ji-soo (they had a falling out but later reconciled) and her relationship with yoo-ri (yoo-ri fell out of affection and ended the relationship coldly), eun-hee learns that lasting relationships need to be built and are hard to come by. this is why her relationship with young-ji, a teacher at her chinese hakwon (after-school tuition), is extra special.

it is easy to see why teacher young-ji is a figure of admiration for the impressionable eun-hee. young-ji lives a quasi-ascetic and independent lifestyle - she dresses in baggy linen, brews oolong tea in a set of china, and in their first meeting teaches eunhee “out of all the people you’ve met in your life, how many of them really know you?” in hanja. she quits her job at the hakwon out of the blue, because she felt like it; she is on a long break from her undergraduate studies at Seoul University, because she felt like it. of course, this independence is afforded by young-ji’s privilege (her family is well-off). but her non-traditional behaviour teaches eun-hee that there are ways to live without conforming to society. she never talks to eun-hee with condescension, but treats her as a mature equal and genuinely cares for her in ways that eun-hee has never received.

in terms of style, i very much appreciated the sensitive directing of kim bora, which drew the viewer very close to the protagonist. there were very clever tricks deployed. there is a moment when eun-hee is caught shoplifting and the shopkeeper asks for her father’s number, to which she whispers “555-2589″. when eun-hee frightfully presses this number into the public phone after she sees the bridge collapse, kim borrows this memory, as the viewer knows who she is calling before she even says a word.

but the best moments were always personal. as a 24 year-old asian female, even the slightest scenes were poignant. when eun-hee ended off her never-delivered letter to young-ji with “when will my life start to shine?” i just started crying, because i wanted to tell eun-hee that her beloved teacher probably doesn’t know. i don’t know too. when the film ended with eun-hee having found an internal peace, through young-ji’s words of advice, that would help her navigate life’s tribulations - big or small - i started to cry again. we have all struggled to find ourselves, amongst the many expectations placed on us in the different roles we play in society. even though not all of us have a figure like young-ji when they were growing up, the answer to finding life tolerable is always the same.

i love this film - i really, really do. i am eun-hee when i was 12, i am young-ji now. i love this film with a camaraderie that is shared between all asian women who have struggled and are struggling to find their places in society. –10/10

this is an arthouse film that probably cannot be appreciated without knowing the tabloid gossip around hong sangsoo and kim minhee. an unapologetic mea culpa for kim through hong, the film is about an actress whose affair with a married director has brought her career to a halt. she returns to korea and her friends tiptoe around her, only alluding to the scandal for fears of her mental wellbeing and outbursts.

i found kim minhee’s character to be unlikeable and admirable - admirable because she defiantly tries to make herself happy at every turn, but unlikeable because this personality takes a toll on her friends around her. at times her friends have to cajole her “you’re really pretty / talented / charming, you know?” “don’t say that… i’m not” “really” “am i…? (in a coy voice) i guess i am … hahaha” – this gets nauseating and repulsive by the second occurrence. stop the self pity please.

i felt the film was hong’s way of apologising to kim, and kim’s way of trying to vindicate herself and gain sympathy with her audience. i appreciated, though, the simple style of hong, whose observation of daily conversations some may find boring. this is vastly different from the corner of korean cinema i have been dwelling in, where wretched histrionics and plot twists are generously employed. – 5/10

a psychoanalysis of an oedipal relationship between kim hye-ja’s nameless Mother and won bin’s mentally-handicapped do-joon, mother is a movie that i unfortunately could not love as much as i wanted to. perhaps its because i’m not a fan of kim hye-ja’s over the top acting (the same reason why i stopped watching the light in your eyes), that a character film built around her was bound to bore and frustrate me with her shaky voice and breathing. the plot was actually predictable with plenty of tropes.

bong’s films are sometimes about post-traumatic castrated males, with a good dose of social ire and commentary. but not really in mother. mother centers around the twisted and overbearing relationship between mother and child, that found little resonance or empathy in me. it offered no critique of people’s attitudes to the intellectually disabled (a rather kind depiction actually), slight critique of the welfare support for single mothers, and more criticism for the bumbling detectives and forensics for clumsily resolving the murder (a trope that is tired and more effective in memories of murder).

unfortunately won bin’s acting could not come to the fore, jin goo was one-dimensionally constructed, the police incompetent (but we already knew that, right), the schoolgirls nubile (waiting for a bong film that undoes this), so all we’re left with at the heart is kim hye-ja’s unloveable character with an over the top acting style that i don’t appreciate. chun woo-hee was the standout for me. – 3/10

(( Lady Vengeance - Just found this old painting on my hard drive from 2009. I did a project on Park Chan Wook films at University ))

Post link