#kumu hina

Jennea’s story is a potent reminder of the difficulties that transgender youth face in school, and the need for clear and consistent policies and training that protect their right to a safe, respectful and inclusive learning environment.

Hawaii, which is fortunate to possess a rich cultural tradition that embraces gender diversity, has at least a basic framework of laws that protect people across the gender spectrum. But the state legislation that explicitly prohibits discrimination based on gender identity or expression in employment, public accommodations, and housing does not yet encompass schools. And although the State Department of Education has a general policy, there is no further guidance on what would constitute discrimination in a school setting. This absence of any specific rules or training by the Department of Education left Jennea’s principal free to interpret the regulations according to her own beliefs.

Nationwide, the majority of school districts have yet to offer any consideration whatsoever for transgender and gender nonconforming students. Worse, many states, including Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Washington and Wisconsin, are now considering legislation that would bring the same sort of discriminatory measures - made infamous by North Carolina’s recent “bathroom bill” - specifically to schools. The Wisconsin bill goes so far as to require school boards to designate each changing room in their facilities “for the exclusive use of pupils of one sex… as determined by an individual’s chromosomes.”

This lack of protection leaves transgender youth vulnerable to discrimination and mistreatment. Not surprisingly, ninety percent of them feel unsafe at school, and one-in-three have been physically assaulted. More than half have at some point avoided going to school due to harassment, and one-in-six have left school altogether, losing their best shot at a solid future.

It doesn’t have to be this way. School districts around the country have developed guidelines and best practices, such as those presented in GLSEN’s transgender model district policy, that protect the right of all students to a safe and secure education. A recent study of seventeen school districts, covering 600,000 students, that implemented such protections did not reveal a single incidence of the “confusion, harassment, or inappropriate behavior” that conservatives had predicted. Indeed, the United States Department of Education has advised schools that failure to treat students consistent with their gender identity leaves them open to legal prosecution under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.

Since Jennea’s video first appeared on Youtube, other students, teachers, and counselors, as well as a highly placed administrator, have come forth to corroborate her experiences at Kahuku High School. Fortunately, Jennea is a strong young woman, with a wonderfully supportive family and friends, and was able to complete all senior year requirements and receive her diploma with the same date as her classmates.

But a diploma is no substitute for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to walk at graduation, or the joy of appearing with your friends in a viral video. Those are gone forever.

This is why we started an online petition calling for the Hawaii Department of Education to establish clear and consistent guidance that will ensure that all students are safe, included and respected in school, regardless of their gender identity or expression. They should also conduct training, professional development and educational activities to ensure that this policy is known and implemented, and that teachers have the knowledge and tools they need to do right by their students.

As opponents of fairness and equality stir fear about transgender people for political purposes, it’s up to open-minded places like Hawaii to demonstrate that respect for diversity and inclusion across the gender spectrum is not just right, it makes us stronger.

You can help by signing this petition.

On Wednesday, April 6, Kamehameha Schools welcomes 1990 graduate Hina Wong-Kalu back to its Honolulu campus for a very special evening of film, music, and conversation.

The public is invited and all are welcome, so please share among friends and colleagues!

The main event will be a screening of A Place in the Middle, a youth-oriented educational video that emerged from Kumu Hina, the award-winning PBS film about her life and work as a teacher.

In addition to a lively talk story with Hina and the filmmakers, attendees will be able to get free copies of the educational toolkit, and be treated to a performance of Hina’s mele – including the inspirational anthem Ku'u Ha'aheo e ku'u Hawai'i - Stand Tall My Hawai'i.

Hawaiian Anti-Bullying Film to Screen at Libraries Statewide

An educational toolkit for safe and inclusive schools.

HONOLULU, HI, Sept. 14, 2015 - TheHawaii State Public Library System will present “A Place in the Middle” - a short Hawaiian film at the heart of a newbullying prevention campaign centered on cultural empowerment and gender inclusion - in a series of screenings at eight selected public libraries statewide from Friday, Sept. 18 through Wednesday, Oct. 28. (See list below for screening locations, dates, and times.)

Created by Kumu Hina Wong-Kalu, and directed by Emmy-winners Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson, “A Place in the Middle” tells the true story of a young girl who dreams of leading the boys’ hula troupe at her Honolulu school, and an inspiring teacher who uses traditional Hawaiian culture to empower her. After each screening, the team will talk story with the audience about the film and educational campaign - supported by Pacific Islanders in Communications, Hawaii People’s Fund, Ford Foundation, and PBS Learning Media.

“We encourage our patrons to learn more about Hawaii’s rich cultural heritage through our libraries’ resources and programs,” said State Librarian Stacy Aldrich. "As community hubs, libraries serve as the perfect venues to host discussions that enable our patrons to connect, learn and celebrate Hawaii’s indigenous and diverse cultures.“

This one-hour program is suitable for students, parents, and educators interested in Hawaiian culture and community-based efforts to make schools safe and inclusive for all. Free DVDs and teaching guides will be available for participants committed to using them in their work.

"A Place in the Middle” Film & Talk Story Events

Sept. 18 (Friday) - 6:00pm: Thelma Parker Memorial Public & School Library (Kamuela, Hawaii Island)

Sept. 29 (Tuesday) - 6:00pm: Kahuku Public & School Library (Oahu)

Oct. 3 (Saturday) - 3:00pm: Kihei Public Library (Maui)

Oct. 7 (Wednesday) - 6:30pm: Waianae Public Library (Oahu)

Oct. 14 (Wednesday) - 6:30pm: Waimanalo Public & School Library (Oahu)

Oct. 15 (Thursday) - 6:00pm: Hawaii State Library (Honolulu)

Oct. 22 (Thursday) - 6:00pm: Hanapepe Public Library (Kauai)

Oct. 28 (Wednesday) - 5:00pm: Molokai Public Library (Kaunakakai)

For more information, contact Library Development Services Manager, Susan Nakata, at (808) 831-6878.

Big Island Now - Sept. 10, 2015:

One Big Island public library will be among seven in the state to present “A Place in the Middle,” a Hawai’i-made anti-bullying film.

The film was made to support a culturally-centered campaign for safe and inclusive schools and will be shown at free screenings across the state between Sept. 18 and Oct. 28.

Thelma Parker Memorial Public & School Library is the film’s first stop. The showing will take place on Sept. 18 at 6 p.m. before traveling to Oahu, Maui, and Kauai.

“We encourage our patrons to learn more about Hawai’i’s rich cultural heritage throughout libraries’ resources and programs,” said State Librarian Stacey Aldrich. “As community hubs, libraries serve as the perfect venues to host discussions that enable our patrons to connect, learn, and celebrate Hawai’i’s indigenous and diverse cultures.”

The one-hour program, created by Kumu Hina Wong-Kalu tells the story of a young Hawaiian girl who dreams of leading a boys-only hula troupe at her Honolulu school and an inspiring teacher who uses traditional culture to empower her. “A Place in the Middle” was directed by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson.

Following the screening, a talk story session will take place with the audience about both the film and the educational campaign. Educational tools, including teaching guides and free DVDs, will be available following the program.

Those who need a sign language interpreter or another special accommodation should contact Thelma Parker Memorial Public & School Library by calling 887-6067 as soon as possible.

It’s back-to-school time in Hawaiʻi. Over 200,000 students will enter grades K-12 this year, full of curiosity and ideas. Unfortunately, many of them will have their studies disrupted and hopes crushed by bullying.

Despite our reputation as the “Aloha State,” surveys show that one-fifth to over one-half of students in both public and private schools have been bullied or harassed. And even though more than 90 percent of voters say that “bullying is important for the state of Hawai'i to address,” attempts to pass a statewide Safe Schools Act have failed repeatedly in the legislature. Some parents, such as a father whose two young children were bullied for years without intervention in East Hawaiʻi schools, have even resorted to suing the Department of Education.

We’re fortunate that several local groups have stepped in to develop their own anti-bullying programs; the E Ola Pono,Adult Friends for Youth Anti-Bullying and Violence Convention, and Mental Health America of Hawaii Pono Youth Program are outstanding examples. Even local comedian Augie T is helping out through B.R.A.V.E. Hawaiʻi, a program started by his daughter after she herself fell victim to bullying.

But bullying doesn’t occur in a vacuum; it’s the product of underlying stigma and prejudice. That’s why it’s time to move beyond telling children that it’s bad to be mean, and start showing them why it’s good to be inclusive and accepting - not just for the targets of bullying, but for everyone in the school and community.

We had the opportunity to witness first-hand the effectiveness of this approach during our two years of filming Kumu Hina, a nationally broadcast PBS feature documentaryabout a Native Hawaiian teacher who empowers her students at a small public charter school in downtown Honolulu by showing them the true meaning of aloha: love, honor and respect for all. It’s a powerful lesson for children and adults alike.

In order to make Kumu Hina’s teaching available to students and teachers in K-12 schools across the islands, we’ve produced a youth-friendly, short version of the film called A Place in the Middle that focuses on the story of one of her students, a sixth grade girl who dreams of joining the boys-only hula troupe. This might make her a target for ridicule and bullying in many schools, but the outcome of this story is very different. It’s a powerful example of why students who are perceived to be different, in one way or another, deserve to be celebrated precisely because of those differences, not simply tolerated despite them.

Overcoming bullying in Hawai'i requires a systemic, long-term, multifaceted approach. The true story of a local girl who just wants to be herself - and in so doing helps her fellow students and entire school - is a good place to start.

A Place in the Middle is available at no cost for streaming and download from PBS Learning Mediaand on Vimeo, and the accompanying Hawai'i Teacher’s Guide can be downloaded from the Hawai'i Educators Website. The program will be touring Public Libraries across the islands beginning this fall.

As the documentary Kumu Hina reveals, living between both genders is the more powerful “mahu" way.

byJade Snow - July 28, 2015:

In traditional Hawaiian culture, creative expression of gender and sexuality was celebrated as an authentic part of the human experience. Throughout Hawaiian history, “mahu” appear as individuals who identify their gender between male and female. Hawaiian songs often contain deeper meanings—called kaona—that refer to love and relationships that don’t conform to contemporary Western definitions of male and female gender roles.

Expressions of sexuality and gender by mahu individuals were often reflected in Hawaiian arts, particularly in traditional hula and music, which continue today. The 2014 documentary Kumu Hina follows the journey of Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu (“Hina”), a teacher—or kumu—at a Hawaiian charter school in Honolulu, who is mahu. Kumu Hina explores the role of mahu in Hawaiian society through the lens of a Native Hawaiian who is deeply rooted in the traditions of her ancestors and committed to living an authentic life.

As a 21st century mahu, Hina’s experience is not unlike many others who defy Western gender classifications. Born Collin Kwai Kong Wong, she struggled to find acceptance throughout her youth. Today, Hina presents herself as a female in her dress and appearance, though she embraces both masculine and feminine aspects of her identity equally. And while the film focuses on her journey to become Hina, it characterizes her by more than her gender identity. The film presents a portrait of Hina as a devout cultural practitioner and educator whose most fundamental identity lies in being Hawaiian.

As a kumu at the charter school Halau Lokahi, Hina instills time-honored traditions and cultural values in her students. One student in particular, middle schooler Ho‘onani, traverses the ever-treacherous waters of youth with the additional strain of identifying as being “in the middle.” Hina relates to Ho‘onani’s journey and challenges the students to create a safe and accepting environment. This proves transformative for Ho‘onani, as her determination to define herself and prove her capability garners her the lead role in the school’s all-male ensemble, which the boys do not dispute. Due to the example Hina sets, her classrooms embrace a new “normal” that openly acknowledges all identities. The result is a confident, empathetic community of young people who validate the complexities of Ho‘onani’s reality and provide her with a compassionate place to grow up.

“It’s all a natural thing,” Ho’onani explains. “Kumu’s in the middle too. Everybody knows that, and it’s not a secret to anybody. What ‘middle’ means is a rare person.” Under Hina’s mentorship, Ho‘onani flourishes, excelling in all areas of study, including music and hula, and earning the respect of her peers. As she prepares for a school event, Hina instructs that shell leis be worn by students based on color: white for the girls and yellow for the boys. Without hesitation, Ho‘onani suggests she wear both, and Hina agrees. “See, you get both—because she’s both,” she explains. This is Hawaiian mahu, unique in its perspective that an individual who has embraced both sides of their gender identity does not require exclusive definition. Those who identify with being mahu may exude more masculine or feminine qualities, but their inner experience is one that ebbs between the two with the grace and subtlety of the ocean tide.

When I interviewed Hina for MANA magazine’s 2014 feature “Beyond the Binary,” she explained: “A mahu is an individual that straddles somewhere in the middle of the male and female binary. It does not define their sexual preference or gender expression because gender roles, gender expressions, and sexual relationships have all been severely influenced by the changing times. It is dynamic. It is like life.” The “changing times” Hina refers to began with the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 1800s and the imposition of Western values on the Hawaiian community. They banned cultural expressions that celebrated diverse sexual views and traditions they believed to be profane, such as hula, and drove them underground. The suppression of traditional Hawaiian values and practices marked a turning point in Hawai‘i’s history, one in which mahu began a struggle to find acceptance.

One of the greatest journeys of the human experience is the struggle to accept oneself and live authentically. Kumu Hina lifts the veil on the misunderstood and marginalized experience of “other” gendered individuals whose identity cannot be defined by the broad strokes of contemporary Western categorization. For many Native Hawaiians, authenticity is at the heart of the human experience. Living authentically is one of the highest honors individuals can bestow upon themselves, their families, and their communities. By embracing her identity, Hina not only fulfills her own personal journey to find love and happiness, but she is able to positively influence the lives of students like Ho‘onani who are grappling with their own identities.

To continue promoting Kumu Hina’s message of acceptance, a 24-minute version of the film and teaching guide were created as an educational resource. This short film, called A Place in the Middle, premiered in February 2015 in Germany and played at Toronto’s TIFF Kids International Film Festival in April. According to co-producer Joe Wilson, the film “has struck a chord with educators and other professionals in need of resources on gender diversity and cultural empowerment.” The film demonstrates healthy ways to address gender identity in the classroom and promotes a safe academic environment for youth to thrive.

Thanks to the determination of Hina and others, the Hawai‘i Marriage Equality Act of 2013 was passed in November 2013. And though further efforts are needed to reach equality, Hina finds validation in her home. “I’m fortunate to live in a place that allows me to love who I love,” she says. “I can be whoever I want to be. That’s what I hope most to leave with my students—a genuine understanding of unconditional acceptance and respect. To me, that’s the true meaning of aloha.”

A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE tells the true story of an eleven year-old Hawaiian girl who dreams of leading her school’s all-male hula troupe. The only trouble is that the group is just for boys. She’s fortunate to have a teacher who understands what it means to be “in the middle” - the Hawaiian tradition of embracing both male and female spirit. Together they set out to prove that what matters most is what’s in your heart and mind.

This youth-focused educational film is a great way to get K-12 students thinking and talking about the values of diversity and inclusion, the power of knowing your heritage, and how to create a school climate of aloha, from their own point of view!

The film is accompanied by a Classroom Discussion Guide that includes background information about Hawaiian culture and history, discussion questions, and lesson plans aligned with the Common Core State Educational Standards and additional educational benchmarks.

The complete film, Discussion Guide, and other resources, including a displayable “Pledge of Aloha,” are available for freeatAPlaceintheMiddle.org. They are also available on the trusted educator’s website PBS LearningMedia, and in hard copy upon request.

From the Berlin and Toronto International Film Festivals to classrooms across the United States, A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE is proving to be a powerful tool to talk about the intersections between gender, identity and culture, and the positive outcomes that occur when schools welcome students with love, honor and respect.

What people are saying about A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE

“An inspiring coming-of-age story on the power of culture to shape identity, personal agency, and community cohesion, from a young person’s point of view.” –Cara Mertes, Ford Foundation

“A valuable teaching tool for students in elementary, middle and high schools, as well as for parents and teachers.” –Carol Crouch, Eleʻele Elementary School, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi

“An amazing tool to help educators understand the need for acceptance for each and every child regardless of gender expression.” –Tracy Flynn, Welcoming Schools

“One of the most positive films about the trans experience I’ve ever seen.” –Jennifer Finney Boylan, author and writer-in-residence at Barnard College

“Uniquely accessible for youth.” –Gender Spectrum

”A true-life ‘Whale Rider’ story.“ –The Huffington Post

Kumu means teacher, and Kumu Hina has a lot to teach the world about how to educate with aloha – love, honor and respect for all. We’ve developed tools to use with both the full documentary KUMU HINA, and a shorter kids’ film called A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE, with students from kindergarten through graduate school. Check it all out HERE.

A brief glimpse of “Kumu Hina” co-producer/director Joe Wilsonʻs June 24, 2015 visit to Mauna Kea. Mahalo nui loa to everyone who shared their manaʻo. View the video HERE. For more information please visit www.protectmaunakea.orgorfacebook.com/protectmaunakea.

A brief glimpse of “Kumu Hina” co-producer/director Joe Wilsonʻs June 24, 2015 visit to Mauna Kea. Mahalo nui loa to everyone who shared their manaʻo. For more information please visit www.protectmaunakea.orgorfacebook.com/protectmaunakea.

Film Explores the Beautiful Way Hawaiian Culture Embraces Trans Identity

San Francisco, Ca. - July 1, 2015: Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson’s Kumu Hina has received the Independent Lens Audience Award, recognizing its status as the highest-rated film of the 2014-2015 season on the acclaimed Emmy and Dupont Award-winning PBS documentary series.

The film tells the inspiring story of Hina Wong-Kalu, a transgender native Hawaiian teacher and cultural icon who brings to life Hawaii’s traditional embrace of mahu - those who embody both male and female spirit. Over the course of a momentous year, Hina empowers a young girl to lead the school’s all-male hula troupe, as she seeks love and a fulfilling romantic relationship in her own life.

“The national broadcast premiere of Kumu Hina happened just as the country was struggling to understand Bruce Jenner’s transition to Caitlyn,” said the filmmakers. “Kumu Hina introduced the American public, mired in the Western mind-set of gender as a simple male-female binary, to Hawaiian culture’s more inclusive and holistic philosophy, one that embraces rather than rejects those who, like Hina, inhabit a place in the middle of the gender spectrum.”

Recently Hamer and Wilson have launched an education campaign around a special children’s version of the film, called A Place in the Middle, that tells the story of the young student through her own words and colorful Polynesian-style animation. The filmmakers are distributing the short video and teaching guides for free on their website and in partnership with PBS Learning Media because “Young people deserve to see a school where everyone is accepted and included,” they said. “We hope this project will help spread Kumu Hina’s message of aloha - love, honor and respect for all - to schools and communities everywhere.”

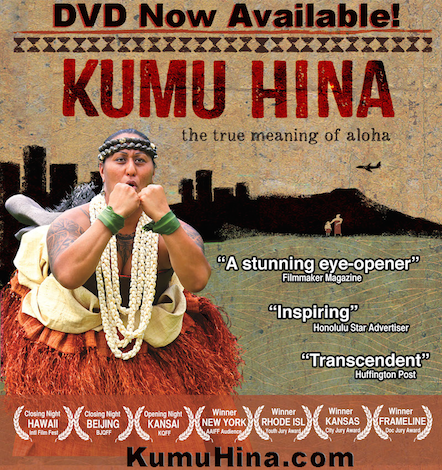

Kumu Hina was funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting,Independent Television Service (ITVS), and Pacific Islanders in Communications. Prior to its national PBS broadcast on May 4, it premiered as the closing night film at the Hawaii International Film Festival, and won numerous festival awards including the Frameline Jury Award for Achievement in Documentary.

Educational and home use DVDs are now on sale. You can also rent or buy a digital copy of the film on VimeooriTunes.

KUMU HINA is a powerful tool for addressing the intersections between culture, gender and identity and is well suited for classes on a variety of topics including Gender, Women’s Studies, Ethnic and Cultural Studies, Sexuality, Health, and Film Studies.

Theeducational DVD package ($295) includes a public performance license that permits unlimited screenings in classrooms and community assemblies. The accompanying Discussion Guide includes information about Hawaiian history, gender diversity around the world, and suggestions for thoughtful conversation and for action.

Kumu Hina herself is also available for personal appearances, either in-person or by Skype, to share her cultural expertise and participate in post-screening discussions.

Contact us for fees and availability. Email:[email protected]

Also, enjoy watching KUMU HINA in the comfort of your home.

Please note this DVD ($24.95) is strictly for personal use. Any school, educational use or public showing must include the purchase of an educational DVD with public performance rights.

There is a $7 shipping charge for destinations outside the USA.

Mahalo!

By Beth Sherouse, Ph.D., May 01, 2015:

Numerous indigenous cultures across the globe have traditions of recognizing a third gender, people who don’t fit within traditional gender binaries or whom we might now call transgender.

While European colonialism sought to suppress or marginalize these identities, some of these traditions have survived and are seeing renewed interest and attention. In some indigenous North American cultures, for example, people identify as two-spirit. In Thai culture, people assigned male at birth but who live as women identify as kathoey.

In native Hawaiian culture, people whose gender identity or expression is somewhere “in the middle” of the binary sometimes identify as māhū, which is the subject of the new documentary, Kumu Hina, premiering Monday, May 4 on the popular PBS series Independent Lens. The film follows the story of Hina, a teacher (or a Kumu in Hawaiian) who identifies as māhū, and her 11-year-old student, Ho’onani, who describes herself as “in the middle.”

The filmmakers, Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer have also made a shorter version of the film called A Place In the Middle – which focuses on Ho’onani and her dream of leading the boys-only hula group at her school – available as a resource for educators to help facilitate discussions on gender. The film is available to stream or download for free from their website.

Filmmaker Dean Hamer explains that “Kumu Hina recognizes that when the class lines up, boys on one side and girls on the other side, there needs to be a place, an actual physical space in the middle” for Ho'onani and other students who don’t naturally belong on one side or the other.”

“In the end, Ho'onani becomes an incredible force and leads the boys into the final performance of the school year, and they come to not only respect her, but really embrace her,” says Hamer. “The strong girl wins at the end.”

“Unlike most educational films, it’s not just about kids, it’s for kids,” says Hamer, and Ho’onani narrates much of her own story. Hamer and Wilson have prepared a guide to help teachers facilitate discussions based on the film about “how gender is interpreted by culture, and how instead of just accepting people who are ‘in the middle,’ this culture celebrates them.”

HRC Foundation Welcoming Schools consultant Tracy Flynn has used A Place In the Middle to work with educators on what welcoming school environments can look like for LGBTQ and gender-expansive kids.

“This film shows one culturally specific story with the universal message of acceptance,” Flynn explains. “It’s an amazing tool to help educators understand the need for acceptance for each and every child regardless of gender expression.”

For more ideas on talking about gender in the classroom, check out the resources available from HRC’s Welcoming Schools. For ways to support transgender and gender-expansive children and youth, visit hrc.org/trans-youth.

Janet Mock of MSNBC’s weekly talk show “So Popular!” talks about how the film title “Aloha” is misused and how Hollywood, in general, has a history of doing this with Hawaiian culture and language. Mock, who’s Native Hawaiian, is frustrated at how some people view Hawai‘i as a “pretty movie backdrop” and don’t learn or understand its culture.

“The ongoing appropriation and commercialization of all things Hawaiian only makes it clear as to why it is inappropriate for those with no ties to Hawai‘i, its language, culture and people, to invoke the Hawaiian language,” she says.

ClickHERE to watch video.

By Nina Wu - Sunday, May 3, 2015:

Standing by the Sun Yat-sen statue at the Chinatown Cultural Plaza, kumu Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu reflected on a recent journey to southern China to explore her family roots.

There, in a small village more than 5,500 miles from home, she found acceptance from long-lost relatives, a powerful testament to the role of family in self-identity.

Being a mahu, or transgender person, as well as both Hawaiian and Chinese, defines her identity “in the middle” and is the subject of a documentary film, “Kumu Hina,” which premieres nationally on PBS’ “Independent Lens” on Monday in celebration of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

The film, by Haleiwa filmmakers Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson, tells of Wong-Kalu’s evolution from a timid high school boy to a confident mahu and respected kumu and community leader in modern-day Honolulu.

All through her struggles, family is what gave her strength.

“My purpose in this life is to pass on the true meaning of aloha — love, honor and respect,” says Wong-Kalu in the film. “It’s a responsibility that I take very seriously.”

Born a boy named Collin, Wong-Kalu was raised by both a Hawaiian tutu on her mother’s side, Mona Kealoha, and a Chinese popo on her father’s side, Edith Kamque Luke.

“My Hawaiian tutu and popo were the most influential in my life,” Wong-Kalu said in an interview with the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. “Both of them raised me to be very cognizant and respectful, and to be very mindful of Hawaiian culture and Chinese culture.”

With both parents working full time, Wong-Kalu spent much of her childhood with extended family — the Hawaiian side in Mililani and the Chinese side in Liliha.

With the Hawaiian side, she was called the “pake child” because of her more Asian looks. The Chinese side referred to her as the “Hawaiian one” because of her darker skin and larger size.

“I grew up in the middle,” said Wong-Kalu, whose parents separated when she was in the second grade. “I grew up not belonging completely to one or the other. Being both, and going to one side, they always consider you ‘the other.’”

So it was, as well, with gender.

Wong-Kalu, 42, remembers from a very young age feeling that she was more female than male. She would sneak into her mother’s closet while she was away at work.

“I’d put on her clothes and high heels and prance around the house for hours on end,” she said. “I wanted to be as beautiful as my mother.”

It was after graduating from Kamehameha Schools in 1990 and attending the University of Hawaii at Manoa that Wong-Kalu fully emerged as a transgender, taking the name Hina.

Besides being teased in elementary and middle schools for being too girlish, she was also taunted for her Chinese name, Kwai Kong, with kids calling her “King Kong” or “Ding Dong.”

“It was very hurtful,” said Wong-Kalu.

She said she found refuge in Hawaiian culture, where mahu — those who embody both the male and female spirit — are respected as a source of ancient knowledge.

Her father’s Chinese side of the family also accepted her transition. During high school Wong-Kalu had stayed mostly in Liliha, becoming the primary caregiver for Luke up to her death in 1997.

“Because I was the caregiver for the matriarch and everybody loved her, they all loved and accepted me,” she said. “She was the kindest one.”

Wong-Kalu has three older siblings — two sisters and a brother, famed Honolulu chef Alan Wong. She said her father, Henry Dai Yau Wong, a former U.S. Army sergeant and man of few words, accepted her as well.

“No matter my father’s internal struggles — and he did struggle — with the changes in my life, he never, ever made me feel less than — ever.”

An invitation to join Hamer and Wilson at the Beijing Queer Film Festival in September turned out to be the perfect opportunity for Wong-Kalu to search for her father’s relatives, with whom the family had lost touch. Through research, Wong-Kalu was able to find the name of her grandmother’s village, Gam Sek, in southern China.

Her popo, Luke, had always kept a framed family portrait in a side cabinet and Wong-Kalu brought a copy of it with her when she and the filmmakers took a two-hour taxi drive past numerous factories to the stone gate at the entrance to the small village.

Upon entering, Wong-Kalu met Luc Lu Moy, wife of a distant cousin. At an ancestral shrine there, she found a matching copy of the family portrait. It turns out a great uncle from Honolulu had brought it with him in the 1970s.

“I burst into tears,” said Wong-Kalu. She placed her lei over the photo.

To introduce herself, Wong-Kalu showed the film to her relatives in China and found they embraced her despite her transgender identity.

“KUMU HINA” follows Wong-Kalu in her former role as cultural director of Halau Lokahi, a Hawaiian public charter school, as she prepares students for an end-of-the-year performance. According to the filmmakers, the documentary is as much about the importance of understanding one’s culture as it is about family and societal acceptance of those who are different.

“This is really a reflection, through Hina’s life, of what family values can mean in the most positive and comprehensive sense,” Wilson said. “With her (students), she often talks about no matter who you are, where you come from, you should know there’s a place in the middle for you.”

A 25-minute version of the film, titled “A Place in the Middle,” is available for free through PBS Learning Media along with a classroom discussion guide for educators.

For Wong-Kalu, finding acceptance from relatives in China, a country where most transgenders largely remain invisible, was affirming. It was in the same spirit of aloha that she lives by.

Standing in Honolulu’s Chinatown, Wong-Kalu cited an inscription below the Sun Yat-sen statue that reads, “All under heaven are equal.”

Besides Beijing, “Kumu Hina” screened at the Hawaii International Film Festival in April 2014 and has been shown on the U.S. mainland and in Tahiti.

“The film emphasizes my life as a Hawaiian, but I am also very influenced by my life as a descendant of some of the very first Chinese that came to Hawaii,” Wong-Kalu said. “The influence on me makes me very devoted to the name of the family and to honor my parents and grandparents.”

On the Net:

» Learn more about “Kumu Hina” - kumuhina.com.

» Learn about PBS/Independent Lens - pbs.org/independentlens/kumu-hina/.

» Watch the trailer - https://youtu.be/MWAM1738JbM.

» Order “A Place in the Middle” with free classroom discussion guide at aplaceinthemiddle.org.

The Huffington Post, April 28, 2015:

In traditional, Western culture, gender identity is often considered a binary concept: You are either male or you are female.

This restrictive and defining construct makes it difficult for our society to understand people like Bruce Jenner, who recently came out as transgender, because they don’t always fit neatly into a box. While some transgender people move from one end of the gender spectrum to the other when they transition, other transgender people exist somewhere in between, embracing both genders, neither genders or a multiplicity of genders.

Ultimately, by changing and broadening our definition of gender identity, we can not only better understand it, we can truly embrace it.

In Native Hawaiian culture, for instance, the idea of someone who embodies both the male and female spirit is a familiar and even revered concept. Gender identity is considered fluid and amorphous, allowing room for māhū, who would fall under the transgender umbrella in Western society.

“Māhū is the expression of the third self,“ Kaumakaiwa Kanaka‘ole, a Native Hawaiian activist and performer told Mana magazine. "It is not a gender, it’s not an orientation, it’s not a sect, it’s not a particular demographic and it’s definitely not a race. It is simply an expression of the third person as it involves the individual. When you find that place in yourself to acknowledge both male and female aspects within and accept the capacity to embrace both … that is where the māhū exists and true liberation happens.”

As an upcoming PBS/Independent Lens documentary "Kumu Hina,” about a transgender woman and teacher, shows, māhū are thought to inhabit “a place in the middle.”

Māhū are valued and respected in traditional Hawaiian culture because their gender fluidity is seen as an asset; the ability to embrace both male and female qualities is thought to empower them as healers, teachers and caregivers.

That ability also helps when it comes to navigating life’s challenges.

“I didn’t take to life as my family’s son,” Hina Wong-Kalu, the subject of Kumu Hina, says in Mana. “I wanted to be their daughter. However, for me to expand my own personal journey and the challenges in my life, I’ve had to embrace the side of me that is the more aggressive, the more Western-associated masculine when I need to. But that’s the beauty of being māhū, that’s the blessing. We have all aspects to embrace.”

Kumu Hina premieres on PBS on Monday, May 4 at 10pm EST (9pm CST).

Hawaiian culture empowers and inspires throughout the islands, from the beautiful dance of hula to the traditions of mahu. For Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu, a cultural advocate and transgender woman at the center of docu-drama Kumu Hina, this culture has defined her life.

Text by Kelli Gratz | Images by Kai Markell - Lei Magazine

In 2011, filmmakers and partners Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson began a cinematic journey—one that neither of them could have anticipated. The subject they started with was Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu, cultural advocate, transgender woman, and Director of Culture at Hawaiian values-based public charter school Halau Lokahi. For the next two years, they followed Wong-Kalu through an interesting time in her life—she had recently married Haemaccelo Kalu, a native of Tonga, and was facing the daily struggles of leading an all-male hula troupe. But throughout the filming process, another story presented itself in the form of a sixth-grade girl named Hoonani, who insisted on joining the troupe. The result of that collision of stories is the gorgeous, inspiring three-character docu-drama Kumu Hina, which comes to PBS in May.

Being in the spotlight seems natural for 42-year-old Wong-Kalu. For more than two decades, she has lived her life as a mahu wahine, or transgender woman, and hasn’t ever looked back. As a child growing up in Honolulu, Wong-Kalu, then named Collin Kwai Kong Wong, knew he was different. He played dress up in his mother’s closet, and as an adolescent attending Kamehameha Schools, was often teased for being too feminine. He felt pressured to be what biology and society deemed him—a boy. But, by the time he was 20 years old, he decided to stop the charade, and transformed into Hinaleimoana, or the goddess of the moon.

Since then, Wong-Kalu has made incredible contributions to the Hawaiian community. A founding member of Kulia Na Mamoa, a community organization aimed to improve the quality of life for mahu wahine, she now chairs the Oahu Burial Council and even ran for a board position on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, one of the first transgender candidates for political office in the United States. Clearly, she does not limit herself to anything or anyone, and believes in the cultural traditions of mahu, respected teachers and keepers of cultural traditions who were never stigmatized or discriminated. “They have the sensitivity for caring and the soft side which is more associated with wahine (women),”Wong-Kalu says. “Yet they have enough aggressiveness and enough strength—the backbone. Not to say that Hawaiian women were not strong … but the mahu had qualities of both man and woman in them.”

In person, Wong-Kalu is equally aggressive and nurturing. Her large figure, covered in Polynesian tattoos, is easily recognizable by many, and her presence is welcomed at community events and gatherings. I recall one in particular: the Hawaii Marriage Equality Bill signing in 2013. Her voice echoed through the corridors, and though I couldn’t understand everything she was saying since she was speaking in her native tongue, Hawaiian, I could feel her ha (spirit). Her oli (chant) was so powerful that days later, I would get chicken skin just thinking about it.

The film’s trailer has a similar effect. It’s a huge, controversial subject told through a captivating love story. A love between a man and a woman, a love shared between a teacher and student, and a love for culture and tradition. Kumu Hina examines the intricacies of a woman who struggled with her identity and the modern-day perceptions of what it meant to be a mahu. Always hovering in the “place in the middle,”Wong-Kalu is figuring out what her next move will be. No matter what, she will continue to speak her opinion, and inspire all around her.

Kumu Hina Premieres on Independent Lens Monday, May 4, 2015 on PBS. For more information, visit pbs.org/independentlens.

To learn more about the documentary and the woman who inspired it, visit kumuhina.comoraplaceinthemiddle.org.

The Birth of Hawai‘i, the Place

The ka‘ao, or sacred records, of the Hawaiian people inform us that the place and space known as Hawai‘i are themselves island descendants of Wākea (sometimes translated as “Sky Father) and Papahānaumoku (literally, the firmament or wide place who gives birth to islands, also referred to as Papa, the creator goddess of Hawai‘i), who conceived and gave birth to the islands of Hawai‘i.

Wākea has many other meanings, two of which speak to the “immensity of our celestial dome.” Another refers to “the zone of Kea.” Kea refers to “enlightenment” and “progeny.” Kea, in simple terms, translates both as “white,” a color associated with spiritual enlightenment and the white of “male procreative fluids.”

Hawaiian creation chants inform us that Papahānaumoku is an extension of Haumea (the-red-sacrifice). Haumea is the lava itself, which, after spewing into the atmosphere of Wākea becomes the solid foundation for living. This intercourse between Wākea and Papahānaumoku also produced the mountain child we know today as Mauna Kea. Mauna Kea isboth female and male. Mauna Kea’s physical manifestations of rock, soil, water and ice, are female attributes; his elevation establishes his maleness, as it brings him closer to the celestial seat of his father Wākea. The equitability of this female-male distribution establishes Mauna Kea as sacred and creates the piko kapu, or sacred center, of the island.

The Birth of Hawai‘i, the Native Being

The ka‘ao also informs us of the birth of Hawai‘i, the native being. Wākea and Papahānaumoku also gave birth to Komoawa and Ho‘ohōkūkalani. Komoawa is both son and high priest of Wākea. Together with Wākea, Komoawa and Ho‘ohōkūkalani established the ancient kapusystem to regulate human impact on the islands that are the sacred children of Wākea and Papahānaumoku.

Ho‘ohōkūkalani means the “creator of stars.” She, in union with Wākea, becomes the celestial womb from which Hawai‘i the original native being takes root, gestates, and is born into a sacred landscape. Yes, the Hawai‘i native, is the descendant of the celestial bodies, the stars themselves. And this moekāpi‘o, or coming together, of Ho‘ohōkūkalani and Wākea, is the primordial union that inserts the Hawai‘i native into the sacred parabola of life between the stars and the earth. The kuahuor shrine to this “arching reality” is Mauna Kea. At birth, the native being is born into a system that ensured thelongevity of the reality of environmental kinship we know as Hāloa.

For this reason, Mauna Kea is sacred. Mauna Kea is where heaven, earth and stars find union. Not just any heaven, but Wākea, not just any earth, but Papahānaumoku, and not just any constellation of twinkling lights, but Ho‘ohōkūkalani, whose children descend and return to the stars.

Mauna Kea ka Piko o ka Moku

Mauna Kea is “ka piko o ka moku,” which means “Mauna Kea is the navel of the island.” Understanding the word pikomay give a deeper understanding of why Mauna Kea is the piko, or navel, of the island.

In terms of traditional Hawaiian anatomy, three pikocan be found. The fontanel is the piko through which the spirit enters into the body. During infancy, this piko is sometimes “fed” to ensure that the piko becomes firm against spiritual vulnerability. For this reason, the head is a very sacred part of the anatomy of the Hawai‘i native. To injure the head of someone can mark the beginning of a long feud that may go on for generations, hence the need to refrain from insulting the head of a person.

The second pikois the navel. This pikois the physical reminder that we descend from a very long line of women. The cutting of this pikois done with ceremony. And when the stump of the piko falls from the belly, the piko“relic” is cared for and put in a location that will be beneficial in protecting the future role and function of the child. Should this pikobe lost or eaten by a rat, it is believed the child will become a wanderer or a thief. Therefore, the bellybutton piko was sealed either in rock or sunk to the bottom of the ocean or placed in the lava to protect it. The care of this piko ensured two things: the healthy function of the child and the certification that the child is a product of a particular land base.

The final piko is the genitalia. The genitalia are the physical instruments that enable human life to continue. The health of all piko ensures that the life of the native person will rest on an axis of spirituality, genealogy and progeny. The absence of one or more piko will prevent an entity from becoming whole or complete.

When we understand the three piko of the human anatomy, we may begin to understand how they manifest in Mauna Kea. Mauna Kea as the fontanel requires a pristine environment free of any spiritual obstructions. Mauna Kea as the umbilicus ensures a definite genealogy of indigenous relation and function. Mauna Kea as genitalia ensures that those who descend from Wākea (our heaven), Papahānaumoku (our land-base) and Ho‘ohōkūkalani (the mother of constellations) continue to receive the physical and spiritual benefits entitled to those who descend from sacred origins.

Thus, Mauna Kea can be considered the piko ho‘okahi, the single navel, which ensures spiritual connections, genealogical connections, and the rights to the regenerative powers of all that is Hawai‘i. It is from this “world navel” that the Hawai‘i axis emerges.

Par Marie-Ange Bartoli - Publié le 25/03/2015 - FranceTV

Hina, une jeune femme transsexuelle de Hawaï, professeur, défend l'image traditionnelle de “mahu” incarnant à la fois l'esprit masculin et féminin. Le documentaire raconte la transformation de Colin Wong, lycéen timide devenu Hina, femme mariée et directrice culturelle d'un école à Honolulu. Dans cette école, il y a une petite fille à la forte personnalité qui veut rejoindre la troupe d'Hina, une troupe de garçons.

See Video Report HERE

February 18, 2015 on the ancient Chinese lunar calendar is New Year’s eve. As I scramble to prepare traditional foods and rituals to usher in the year of the goat, I found myself reflecting on the powerful convictions of a great teacher. You may not have heard of her yet, but I’m sure that in due time, you will because Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu (黄貴光) has an inspiring spirit that shines bright on and off the screen. Hinaleimoana is the starring character in a feature documentary called Kumu Hina showing at CAAMFest this year. Here’s an excerpt of an interview I did with her and filmmakers Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson.

—Kar Yin Tham, Center for Asian American Media

Can you talk about how Hawaiian culture became such an important part of your life, in terms of teaching traditions?

Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu: Well, on both sides of my family, I was exposed to the strength [from] both my grandmothers actually. My Hawaiian grandmother, she insisted that I be staunch and fastidious about language and accuracy of our culture. She advocated for me to establish a Hawaiian sense of place, Hawaiian presence, Hawaiian manner, a Hawaiian sense of decorum. And she did this because Hawai’i in my growing up was such a rapidly changing place that I know now, later in life, that Hawai’i was so very different from what she knew.

So you were raised by your grandmother?

HW: I have been reared primarily by her and my Popo, my Chinese grandmother. She shared much with me that she did not share with my mother and her siblings. My Popo, in her own way, was the same kind of person but more from a place of being. You know, I had this engrained into me growing up that both grandmothers were staunchly holding on to what they could just by virtue of the fact that were bi-cultural.

During Chinese New Year, offering tea to our family is the one of the last few things that I still am able to do. You can’t replace that. [If] there’s any one day out of the year you can’t miss, it’s new year. A birthday you might be able to get away with. But you must show up for Chinese New Year, and wish your elders Gong Hei Fat Choy (“Happy New Year” in Cantonese).

Why is it so important for us to have that connection to tradition?

HW: What is modern life? And who dictates modern life? And who sets the standards? And who says that modern life is equated to Western life? And that it is better? For me, that’s been more detrimental. I’ve had to wrestle with, am I going to embrace the mainstream trends that assimilate my manner of engagement and my interaction with people to something more Western? And I say, no, this how I’m going to be. Because if I don’t say it, that I’m going to [live] in the way that I understand my people to be, then what’s the sense of holding onto language? What’s the sense of trying to hold onto culture? It would become a shell. If I were to engage in the Chinese language, but then I had no sense of the Chinese understanding of respect, but I just used the words, it’s an empty shell. Ornamental culture – I’m not a fan of that at all.

Is tradition something you try to communicate to the students? And do you feel like its working, because there are a lot of factors against it?

HW: Yes, It works in ways that are not always so obvious. They will realize what they’ve learned when they go. Just before I came up here (San Francisco), I ran into one of my former students. And he didn’t graduate with us, but he had a very, very rough road with us, and he was released because of it. He shared with me, “Thank you Kumu. You know, I remember you teaching us this.” He was extending a helping hand with someone he didn’t always get along with when he was in school [Hālau Lōkahi Public Charter School]. But this other former schoolmate was down and out. And he gave him a helping hand and he said, “I remember that you taught that to us. And that’s how it has to be.” So then I know that, this young man who has been through his life ordeals and now is a father of two is practicing what he was taught. So that’s one of the biggest rewards to have.

Can you talk more about how gender is portrayed in the film?

Dean Hamer: I’d say that, the way we made the film was simply to follow Hina. We didn’t set out to say we were going to make a film about gender. We said we were going to make a film about Hina. When Hina lives her life, gender comes up a lot.

HW: You know, in the Western context, for the transgender, “passing” or “being passable” for a female to male that has to tie her breasts, for the male the facial hair, an Adam’s Apple and all of these things that are the giveaways for what your true nature is, but in Pacific Island culture there’s more freedom and fluidity to be somewhere in between, but you find the conflict when you have to engage with Western society.

With more traditional elements of Hawaiian society, there are clear roles for the male and for the female, but the definition and the articulation of that is not the same as Western eyes would have it. So, when I say articulation, I mean the physical articulation of a male and a female.

In the film, it shows my friends on the island of Kauai and, you know, they’re certainly very, very androgynous. There’s elements of them that are feminine—Western feminine—and there’s also elements of them that are Western masculine. And there’s no issue.

These are all things that, by Western context, will divide you. Are you this or are you that? But really, it’s the roles that you live. So, the fluidity comes in when you consider that the mahu can exist somewhere in there, but it’s all context specific.

Joe Wilson: It is for Western audiences to view the film in a way that allows them to see how people live in family, community and society outside of construct of labels and who people are supposed to be.

DH: Outside of strict male female labels.

HW: Yes, and for me, I do not like the fact that we are consistently imposed upon by these values that … someone from within the LGBT Western perspective have to be so separate and distinct, and this whole idea about a way of life. But, I do not agree with that. I’d rather just be myself, and encourage others to participate in the larger fabric of community and family life.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kumu Hina screenings

Co-presented by Frameline and sponsored by Pacific Islanders in Communications and Cooper White & Cooper.

New People Cinema

March 13, 2015 7:40 pm

Buy Tickets

PFA

March 15, 2015 3:30 pm

Buy Tickets

byChad Blair for Hana Hou: The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines

There’sa scene in the filmKumu Hina in which the hula teacher at Halau Lokahi stands facing sixboys slouching in a doorway of the public charter school in Honolulu.The tattooed, five-foot-ten-inch-tall kumu (teacher) looks imposing despite the yellow plumeria tucked behind her ear. “Stand up straight. Stand tall,” she commands. She demonstrates: shoulders back, feet rooted. “I need this. This is what I need from you, all the time.” The boys comply, looking uncomfortable. Once the kumu is satisfied, she invites them to enter and sit before her. She belts the opening line of a chant from Hawai‘i Island hula teachers: “‘Ai ka mumu keke pahoehoe ke!” Her voice resounds in the huge space as she waits for them to repeat it.

It’s all in a day’s work for any kumu trying to whip a group of hula-challenged high school boys into performance-ready shape. Forty-two-year-old Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu is a kumu hula, cultural practitioner and activist; the acclaimed documentary film based on her life premiered in April 2014 at Hawaii Theatre and has been shown on the Mainland and in Asia. It will be featured at the Pacific International Film Festival in Tahiti this February and air nationally in the United States on PBS in May. Kumu Hina is a portrait of a respected cultural practitioner passing Native Hawaiian values to her students. It is a love story, too, between Hina and her Tongan husband. More than anything it is the story of what it means to be mahu.

Kumu Hina has a long way to go with these boys. They try sheepishly to imitate her chant, their voices weak. Hina gently mocks them by whispering back: “‘Ai ka mumu keke …? No. Listen to my voice. There’s nothing wahine [female] about my voice. It’s thick and it’s too low.” She clears her throat, then chants the phrase again, deeper, louder and with almost physical force. The boys laugh, embarrassed and unnerved. Then she addresses them seriously, directly. “When I am in front of the entire school,” she intones, “you guys know that I expose my life. What the younger kids think about me, that’s up to them. But you, as older people, know.” What the boys know—and accept without question—is that their kumu was born male. “Now you, gentlemen,” says Kumu Hina, “gotta get over your inhibitions.”

Before the arrival of American missionaries in 1820, Hina explains in the film, every gender—male, female, mahu —had a role. Native Hawaiians believed that every person possessed both feminine and masculine qualities, and the Hawaiians embraced both, regardless of the body into which a person was born. Those in the middle—mahu—were thought to possess great mana, or spiritual power, and they were venerated as healers and carriers of tradition in ancient Polynesia. “We passed on sacred knowledge from one generation to the next through hula, chant and other forms of wisdom,” Hina narrates. After contact with the West, however, the missionaries “were shocked and infuriated. … They condemned our hula and chants as immoral, they outlawed our language and they imposed their religious strictures across our lands. But we Hawaiians are a steadfast and resilient people. … We are still here.”

From an early age Collin Kwai Kong Wong knew he was “different,” as Hina puts it now. “I wanted to be as beautiful and glamorous and smart as my mother. I wanted to be this beautiful woman. When my mother would go to work and leave me at home alone, I was in her closet.” Hina laughs recalling this, but it was hardly funny when it was happening: Collin was teased for being too feminine, and he didn’t know how to talk to his family about what he was going through. He tried, like others in such situations, to conform. “I had girlfriends when I was younger, and I tried to play the role,” Hina recalls. “I tried to be the person that I thought my friends and family were expecting to see.”

Collin learned Native Hawaiian values through his grandmother, but it wasn’t until he enrolled at Kamehameha Schools that he learned the practices: hula, oli and ‘olelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language). After graduating he worked as an assistant to a kumu hula and traveled throughout the Pacific to places like Tahiti and Rarotonga.

Back home in the Islands, he connected with Polynesians from other island groups, particularly those from Samoa and Tonga, among whom he felt more comfortable expressing his feminine side. “They had a more inclusive way about them,” Hina says. “It seemed easier to migrate toward transitioning into how my heart and spirit felt and know that there would still be a place for me. That I could be myself and people wouldn’t look at me with such scrutinizing eyes.”

Hina was delicate with her family as she began to transition at 20 years old, though her Hawaiian mother nonetheless struggled with it. “How did I transition from being my family’s son to being my family’s daughter? Not by throwing it in their face. Not by being militantly loud and obtrusive,” she says. Her Chinese father, perhaps ironically, was more accepting. “He said, ‘I don’t care what you do in your lifetime, just finish school and take care of your grandmother.’ He didn’t impose other things on me, and that said to me that my father would accept me unconditionally.”

Collin chose the name Hinaleimoana. Hina is the Hawaiian goddess of the moon, among the most desired figures in Polynesian mo‘olelo (stories), a name she says honors her mother’s cultural heritage and one that Hina hopes to “live up to.”

Hina had been teaching at Halau Lokahi for ten years when filmmakers Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer met her in 2011 through a mutual friend, Connie Florez, who became a co-producer of Kumu Hina. Wilson and Hamer were already known for their Emmy-winning 2009 film Out in the Silence, which chronicles Wilson and Hamer’s same-sex wedding and the uproar it subsequently caused in Wilson’s Rust Belt hometown of Oil City, Pennsylvania. Wilson and Hamer saw Hina’s story as a fresh approach to the topic. “As people who come from the continent, we often have a superficial understanding of Hawai‘i,” Wilson says. “Meeting Hina introduced us to a Hawai‘i that we might not otherwise know about. When she embraced us as filmmakers to document her story, we realized that this is a Hawai‘i that everybody needs to know about.”

That Hina was both respected and approachable was evident from their first meeting with her. “As we went to dinner at Kenny’s in Kalihi, just walking from the parking lot to the restaurant took about thirty minutes,” says Hamer. “There were so many people who knew her and came up to her. Coming from the Mainland, where a mahu might be looked at as suspicious, it was so different and wonderful to see her as part of her community.”

The crew shadowed Hina for two years and just let the cameras roll, often capturing touching moments between Hina and her students as well as a surprisingly intimate and honest view of her marriage. They filmed at Halau Lokahi, in her home and in Fiji. Much of the film focuses on Hina’s poignant relationship with a tough and talented middle school student, Ho‘onani Kamai, a girl who, like Hina, is “in the middle” and who, despite being female and considerably younger, confidently directs the high school boys as they practice their hula and leads them during the end-of-year performance. Wilson and Hamer are editing an age-appropriate version of the film that emphasizes Ho‘onani’s story to be shown in Hawai‘i schools. (The working title: A Place in the Middle.) “It’s told through the students’ point of view,” Wilson explains. “The value of that film is to reach people in the classroom setting.”

For her part, Hina says she is happy with the film and its success, though she insists that she didn’t do it for the stardom. “I don’t need the glory, I don’t need the fame,” she says, “but who doesn’t appreciate a pat on the back? What I want to know is that there is value and worth in my life—not the everyday value, but the larger value. Can I serve our people? Can I serve our community in ways big and small? I firmly believe that through being oneself, through living one’s truths and embracing one’s realities, others may find strength and courage.”

Not only are Hawaiians “still here,” as Hina says in the film, but once-suppressed native traditions like oli and hula are flourishing, and aikane (same-sex) marriages are today protected by Hawai‘i state law.

During the 2013 bill-signing ceremony for same-sex marriage in Hawai‘i, Kumu Hina delivered a stirring oli that sounded as if it roared from the caldera of Kilauea. She chanted before a packed auditorium of government officials, marriage equality advocates and friends and families at the Hawai‘i Convention Center. Those in the audience who did not understand Hawaiian wouldn’t know that Hina sang of “a new dawn.” But when Hina chanted about “the precious day of the aikane and of the mahu,” many in the audience laughed, clapped and whooped upon hearing the word “mahu,” causing the kumu herself to stop for a moment and break into a smile. (You can view the clip, with English subtitles, on YouTube.)

While she says she was honored to be asked by then-Governor Neil Abercrombie to deliver the oli, she did so “to be a catalyst for this change” and not, she says, to become a standard-bearer for LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) issues. That’s not a label, she says, that suits her; “I am not someone who wants to embrace LGBT and apply it to myself,” she says. Rather, it is her Hawaiian identity that predominates; if working in support of LGBT issues helps to serve that larger purpose, Hina is willing. But she points out that LGBT interests might well be served indirectly. “I put my-self out there for the larger community,” she says, “and if I do good for the larger community, then a more positive light will be cast on people like me.”

Last fall Hina concluded thirteen years as cultural director at Halau Lokahi. She’s still considering what she’ll do next, but whatever it is, it’s likely that she will advocate on behalf of Native Hawaiians. In 2014 she ran unsuccessfully for a position on the board of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Hina also chairs the O‘ahu Island Burial Council, which ensures that iwi kupuna—the remains of Hawaiian ancestors—are treated properly when they are unearthed during construction projects. Jonathan Likeke Scheuer, who served as her vice chairman before his term ended last June, praises Hina’s ability to reach consensus between developers and descendants —no small accomplishment, he points out, given the intensity of the disputes that erupt over the treatment of iwi kupuna. “Her leadership comes from an absolutely culturally grounded place,” Scheuer says. “She is so comfortable in her own skin, in being the person she is. She embodies who she is in this wonderful way that is really the source of her power.”

“I really don’t know what’s in store,” Hina says at the end of the film, and though she’s referring specifically to her marriage, she might as well be talking about her life as a whole. “What I do know is that I’m fortunate to live in a place that allows me to love who I love. I can be whoever I want to be. That’s what I hope most to leave with my students: A genuine understanding of unconditional acceptance and respect. To me that’s the true meaning of aloha.”

KUMU HINA: A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE to Premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival, February 5–15, 2015

Produced & Directed by O'ahu residents Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson in association with Pacific Islanders in Communications, the film tells the story of a young girl who aspires to lead her school’s all-male hula troupe and a teacher who uses Hawaiian culture to empower her.

“A true life Whale Rider!” -Huffington Post

January 20, 2015 – (Haleiwa, HI) – KUMU HINA: A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE is one of 65 films from 35 countries selected for the 65th Berlinale’s Generation programme, a slate of state-of-the-art world cinema devoted to children and young people seen by more than 60,000 attendees annually.

Firmly grounded in their respective cultural contexts, the selected films paint sensitive portraits of extraordinary characters often living in hermetically sealed worlds. “We experience young people who bear too much weight on their shoulders,” as section head Maryanne Redpath describes one of this year’s recurring themes. “The high degree of self-determination with which these children and adolescents liberate themselves from their predicaments is striking.”

A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE is the educational version of Hamer and Wilson’s feature documentary KUMU HINA, which was the Closing Night Feature in the Hawai'i International Film Festival’s 2014 Spring Showcase. The film has traveled the world for festival, campus, and community screenings, and will have its national PBS broadcast on Independent Lens on May 4, 2015.

In A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE, eleven year-old Ho'onani dreams of leading the hula troupe at her Honolulu middle school. The only trouble is that the troupe is just for boys. She’s fortunate that her devoted teacher, Kumu Hina Wong-Kalu, understands first-hand what it means to be ‘in the middle’ – embracing both male and female spirit. Together, as they prepare for a big year-end public performance, student and teacher reveal that what matters most is what’s in one’s heart.

With nearly 500,000 visitors each year, the Berlinale is the largest publicly attended film festival in the world. A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE was one of over 5,000 submissions to the festival this year, and the only selection from Hawai‘i.

“An inspiring coming-of-age story on the power of culture to shape identity, personal agency, and community cohesion, from a young person’s point-of-view.” -Cara Mertes, Ford Foundation’s JustFilms

“I know that this film will bring understanding and enlightenment to all who view it.” -Leanne Ferrer, Pacific Islanders in Communications

Festival info: https://www.berlinale.de/en/presse/pressemitteilungen/alle/Alle-Detail_26456.html

Film web site: http://aplaceinthemiddle.org/

by Dean Hamer - Jan. 7, 2015:

My usual questions as I get ready for a film festival are whether we’ll be able to sell out the show and how the audience and local press will react. Preparing for the Beijing Queer Film Festival last September, I had a different sort of concern: would I be able to show our film without being arrested?

The festival had invited me, my partner Joe Wilson and our main character, Hina Wong-Kalu, to screen Kumu Hina, a documentary about Hina’s life as a highly regarded native Hawaiian teacher and cultural leader who just happens to be māhū, or transgender. Because China has a censorship law that prohibits any positive depiction of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender lives in movies or TV shows, mainstream venues were out of the question; the big international festivals in Shanghai and Beijing are devoid of gay-themed films, and DVDs of Brokeback Mountain are only available on the black market.

Which is exactly why the very existence of the Beijing Queer Film Festival is both so necessary and so audacious. Founded in 2001 by openly gay filmmaker Cui Zi’en, the early years were difficult. Screenings were cancelled by the security police at the last minute, films were moved from theaters and universities to bars and private homes, publicity was largely by word of mouth and organizers were threatened.

Then in 2013, for the first time, the festival went off without a hitch. Buoyed by the lack of governmental interference, the organizers for the 2014 edition decided to open up the festival by holding the screenings in a public cinema and marketing to the large Beijing LGBT community through social media.

Their timing was unfortunate. Last year was tough on progressive causes in China, as President Xi Jinping led a series of crackdowns on independent voices, arresting critics and shuttering NGOs. The most troubling was the brutal shutdown of the Beijing Independent Film Festival in late August. Authorities forcibly dispersed would-be audience members, shut off the venue’s electricity, and detained the organizers, seizing documents and precious film archives from their offices.

The Queer Film Festival organizers quickly recalibrated their approach, abandoning the idea of using a public cinema and cutting back on their social media activities. But the police were watching. Just weeks before the festival, two security officers paid a visit to festival co-director Jenny Man Wu — a young straight woman with a passion for queer cinema.

“We’ve tapped your phone and read all your emails,” they told her, “and if you go ahead with the festival as planned, there will be trouble.” These are not good words to hear out of the mouth of a Chinese policeman.

But LGBT Chinese are, by necessity, as resourceful as they are resilient. Shortly after arriving in Beijing, on the day before the opening of the festival, we received an email from an unfamiliar address telling us there was a new plan. We were instructed to go to the central Beijing railway station the next morning, purchase tickets for the 11:15 AM train to a town near the Great Wall, and proceed to car number 7. “Make sure to bring your laptops,” the note ended.

And so the next morning we found ourselves in a commuter train car filled with a colorful mixture of Chinese queer film buffs, filmmakers, academics, artists and activists. The organizers handed out flash drives containing the opening film, Our Story, an artful retrospective of the festival’s history. We counted down in unison, “san, er, yi”, then started our media players together. The Beijing Queer Film Festival was underway.

The rest of the festival went off without major incident.Most of the films were from China, which despite the pressure from the authorities has a growing gay indie movement, others from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea and Europe. There were features, documentaries, a variety of shorts including several student films, and panels on topics ranging from “Light Documentary, Heavy Activism” to “Women on Top.” Most of the screenings and panel discussions took place at the Dutch Embassy, beyond the purview of the Chinese authorities.

Kumu Hina, the closing night film, was screened in the basement of a nondescript building housing several NGOs. Despite its location in an obscure hutong, or old alley district, the room was packed and the reception ecstatic. There was even some press, which led to a feature article in “Modern Weekly” on Hina’s experience, as a person of mixed Hawaiian and Chinese descent, visiting the homeland of her father’s side of the family for the first time.

In the USA, many LGBT film festivals are struggling as queer movies become readily available in mainstream theaters and on TV and the web. For Joe and me, what made the Beijing screening among the most moving and memorable experiences we’ve had on the festival circuit was the realization that it was more than an entertainment, it was a statement. Every single person in the room was risking something – perhaps even their own freedom – just to be there. It was a rare opportunity to see how a community under duress depends on the power of film and storytelling to help bring about change.

by Cara Mertes, Roberta Uno, & Luna Yasui:

As grant makers at the Ford Foundation, we’re accustomed to collaborating. Our initiatives—Advancing LGBT Rights,JustFilms, and Supporting Diverse Arts Spaces—not only intersect; they also reinforce each other. When we work together, we’re reminded that three voices can truly sing louder than just one—an idea that was exemplified at a recent film screening and live performance.

On December 10, the foundation hosted 2014’s final JustFilms Philanthropy New York screening and performance series, this time celebrating cultural icon Kumu Hina, a transgendered Native Hawaiian activist and teacher, and the subject of the evening’s film. After her beautiful chanted greeting (a Hawaiian oli), she was joined on stage by world-renowned Hawaiian musicians Keali'i Reichel and Shawn Pimental, whose music brought the refreshing trade winds of Hawaii to a cold New York evening. By the time Kumu Hina returned to perform a hula, the 300-strong audience had been transported to a world of grace, revelation, and aloha.

The performances were the perfect prelude to the screening of Kumu Hina. Directed by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson, the film tells the inspiring story of Hina Wong-Kalu, also known as Kumu Hina. In high school, she was a young man named Colin Wong, who harnessed Hawaiian chant and dance to embrace his sexuality as a māhū, or transgender person. As an adult teacher, Kumu Hina supports a young girl student, Hoʻonani, as she fights to join the all-male hula troupe, pushing against the boundaries of conventional gender roles. Kumu Hina provides a holistic Native Hawaiian cultural context that affirms Hoʻonani as someone who is waena (between) and empowers her to move fluidly in her identity.

Kumu Hina’s story centers on the power of culture to shape identity, personal agency, and community cohesion. It transcends the cliché of a young person coming of age through dance, because it is grounded in a Pacific Islander value system that offers a fluid way of understanding and valuing identity—giving us all fresh ways to see each other with empathy. The film also points to Hawaii’s leadership as the first state to have two official languages, English and ʻŌlelo Hawai'i; as an early proponent of gay marriage; and as a model for a polycultural America, where culture and values influence each other and move fluidly across boundaries rather than live side by side, or in a hierarchy, as separate entities. But ultimately what makes this film so memorable is that it allows audiences to experience the incredible journey of one person and her community, teaching people everywhere to see, appreciate, and truly embrace LGBT people.

This special event demonstrated how arts and culture, including film, dance, and music, serve as a central means of self-expression and political activism for LGBT people of color. They also exemplify how partnerships—those three voices singing as one—can help amplify a powerful story and support our grantees as they reach for a wider audience.

Watch Hina in performance with Keali'i Reichel & Shawn Pimental here: