#mieko kawakami

MK: I’m talking about the large number of female characters who exist solely to fulfill a sexual function. On the one hand, your work is boundlessly imaginative when it comes to plots, to wells, and to men, but the same can’t be said for their relationships with women. It’s not possible for these women to exist on their own. And while female protagonists, or even supporting characters, may enjoy a moderate degree of self-expression, thanks to their relative independence, there’s a persistent tendency for women to be sacrificed for the sake of the male leads. So the question is, why is it that women are so often called upon to play this role in Murakami novels?

HM: Now I see, okay.

MK: Would you mind sharing your thoughts on that?

HM: This may not be the most satisfying explanation, but I don’t think any of my characters are that complex. The focus is on the interface, or how these people, both men and women, engage with the world they’re living in. If anything, I take great care not to dwell too much on the meaning of existence, its importance or its implications. Like I said earlier, I’m not interested in individualistic characters. And that applies to men and women both.

MK: Most women in the real world have had experiences where being a woman made life unlivable. Like victims of sexual assault, who are accused of asking for it. It comes down to the fact that making a woman feel guilty for having a woman’s body is equivalent to negating her existence. There are probably some women out there who have never thought this way, but there’s an argument to be made that they’ve been pressured by society into stifling their feelings. Which is why it can be so exhausting to see this pattern show up in fiction, a reminder of how women are sacrificed for the sake of men’s self-realization or sexual desire.

HM: I think that any pattern is probably coincidental. At a minimum, I never set things up like that on purpose. I guess it’s possible for a story to work out that way, on a purely unconscious level. Not to sound dismissive, but my writing doesn’t follow any kind of clear-cut scheme. Take Norwegian Wood, where Naoko and Midori are respectively grappling with their subconscious and conscious existences. The first-person male narrator is captivated by them both. And it threatens to split his world in two. Then there’s After Dark. The story is propelled almost exclusively by the will of the female characters. So I can’t agree that women are always stuck playing the supporting role of sexual oracles or anything along those lines. Even once I’ve forgotten the storylines, these women stay with me. Like Reiko or Hatsumi in Norwegian Wood. Even now, thinking about them makes me emotional. These women aren’t just novelistic instruments for me. Each individual work calls for its own circumstances. I’m not making excuses. I’m speaking from feeling and experience.

MK: I see what you mean. As a writer myself, I’m thoroughly familiar with what you mean by feeling. At the same time, I can see how readers might come away with the kind of reading experience we’ve been discussing.There’s something really important to me about what you’ve been saying, this idea that in your opinion, women can go beyond sexualization, or exist wholly apart from it, and take the story in an entirely different direction.

HM: Right. I do feel that women have rather different functions from men. Maybe it’s cliché, but this is how men and women survive—helping each other, making up for what the other lacks. Sometimes that means swapping gender roles or functions. I think it depends on the person, and on their circumstances, whether they see this as natural or artificial, as just or unjust. Whether they see gender differences as involving stark opposition, or being in harmonious balance. Perhaps it’s less about making up for what we lack, so much as cancelling each other out. In my case, I can only tackle these complicated questions through fiction. Without demanding it be positive or negative, the best that I can do is approach these stories, as they are, inside of me. I’m not a thinker, or a critic, or a social activist. I’m just a novelist. If someone tells me that my work is flawed when viewed through a particular ism, or could have used a bit more thought, all that I can do is offer a sincere apology and say, “I’m sorry.” I’ll be the first guy to apologize.

A Feminist Critique of Murakami Novels, With Murakami Himself (Mieko Kawakami Interviews the Author of Killing Commendatore)

–

“If you look for women in fiction, you’ll find them everywhere—novels, movies, and of course in anime, perhaps Japan’s main cultural export—but they are almost always assigned supporting roles, sexualized and self-sacrificing. It doesn’t matter how young or old the woman is, it would seem she has no choice but to walk one of two paths: the mother or the whore.”

“Then, about ten years ago, men and women alike started asking one question with particular urgency: “How do you feel about Murakami’s representation of women?” The question had such gravity that it was impossible to ignore. Answers ran the gamut. Some wished that he would handle women with the same creativity that he summoned when writing about men (or wells). Some said “The women make themselves unreasonably available,” while others said “I don’t see anything wrong with this.” Meanwhile, some said they actually thought Murakami’s depictions of women were realistic—even convincing.

Then they would turn to me and ask: “What do you think?”

I understand what’s at stake. Among the true pleasures of reading a tale spun by Murakami is the way he makes the world we know a foreign place. Oftentimes, sex functions as a skeleton key, allowing his protagonists access to other worlds. As these protagonists are overwhelmingly heterosexual and male, women must take on the role of sexual accomplice. I recognize that this pattern is present in no small number of his works, and I can understand that there is something to be learned from paying attention to this pattern. But what can we actually understand from this sort of pattern? The author’s personal ethics, obsessions, or attitude toward the world? Does it speak to something in his work obscured beneath the surface? All of the above? When we uncover these patterns, how does that substantively transform the thing we’ve read?”

“We just need to recognize that there is no single standard by which all works ought to be evaluated. The possibilities are infinite. Feminist criticism is one such possibility—one among many—but one that offers insights not otherwise available.”

Acts of Recognition: On the Women Characters of Haruki Murakami (Mieko Kawakami Considers the Work of One of the World’s Great Novelists)

Title: Heaven

Author:Mieko Kawakami

Translators: Sam Bett and David Boyd

Publication Date: September 2009 (original), May 2021 (translation)

Publisher: Europa Editions

Genre: fiction

Not that you can ever be in the right mindset to read about violent bullying, but I couldn’t get into the deeper themes of power and (self-)perception that Kawakami had woven into the story. She uses bullying as the tool to get those points across, and frankly, it was a bit gratuitous at times.

I also felt the story itself didn’t quite come together in a way that would hold your attention, most likely because I was taken aback by the sheer amount of bullying that was happening across the pages. However, even without the exorbitant amount of bullying, the story felt a bit disconnected. I can’t quite tell if this is a translation issue (which I don’t think it is, because Breasts and Eggs was fine) or what, but I felt something was missing. There was also that ending that I had mixed feelings about that kind of lean towards negative.

Kawakami still writes with a distinct voice and does an amazing job with imagery (well, maybe for worse in this case…) that I think makes her stories worth reading. However, I wasn’t as invested in Heaven as I was in Breasts and Eggs.

Content Warning: bullying, violence, suicide/suicidal thoughts, eating disorder, physical and emotional abuse, ableism, body shaming

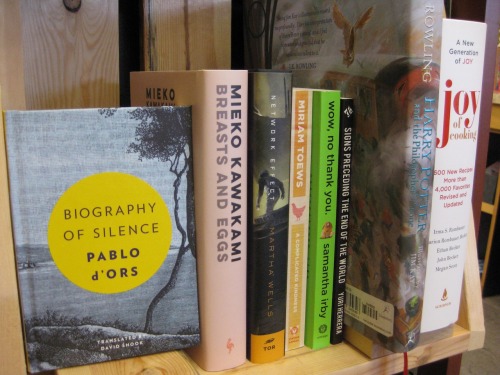

Our first week open to browsing has gone wonderfully! Thanks to everyone who’s come in to show their support. You guys are the BEST.

As a thank you and maybe some enticement, here are some of our favourite reads of the year. What are yours?

Post link

Moodboard: A Gemini Winter Book List.

- Heaven by Mieko Kawakami.

- All’s Well by Mona Awad.

- Mansfield Park by Jane Austen.

- The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell.

- Valerie and Her Week of Wonders by Vitezslav Nezval.

Post link