#pilgrimage

Cloister from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert

French

Late 12th c.

Limestone

‘Situated in a valley near Montpellier in southern France, the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert was founded in 804 by Guilhem (Guillaume) au Court-Nez, duke of Aquitaine and a member of Charlemagne’s court. By the twelfth century, the abbey had been named in honor of its founder and had become an important site on one of the pilgrimage roads that ran through France to the holy shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. With the steady visits of travelers en route to the shrine and the gifts they brought with them, a period of prosperity came to the monastery. By 1206 a new, two-story cloister had been built at Saint-Guilhem, incorporating the columns and pilasters from the upper gallery seen here. Most of these columns are medieval versions of the classical Corinthian column, based on the spiny leaf of the acanthus. This floral ornamentation is treated in a variety of ways. Naturalistic acanthus, with clustered blossoms and precise detailing, is juxtaposed with decoration in low, flat relief, swirling vine forms, and even the conventionalized bark of palm trees. Among the most beautiful capitals are those embellished by drill holes, sometimes in an intricate honeycomb pattern. Like the adaptation of the acanthus-leaf decoration, this prolific use of the drill must have been inspired by the remains of Roman sculpture readily available in southern France at the time. The drilled dark areas contrast with the cream-colored limestone and give the foliage a crisp lacy look that is elegant and sophisticated.

Like other French monasteries, Saint-Guilhem suffered greatly in the religious wars following the Reformation and during the French Revolution, when it was sold to a stonemason. The damages were so severe that there is now no way of determining the original dimensions of the cloister or the number and sequence of its columns. Those collected here served in the nineteenth century as grape-arbor supports and ornaments in the garden of a justice of the peace in nearby Aniane. They were purchased by the American sculptor George Grey Barnard before the First World War and brought to this country. A portion of the original cloister remains at Saint-Guilhem.’

The cloister is in the collection of The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Description and image taken from the Met’s website. You can see more photos of the cloister here on their site.

(**Tour 4/5)

Post link

THE EINSIEDELN ITINERARY

The library of the Benedictine monastery of Einsiedeln contains a miscellany (Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek Codex 326) compiled over the 9th and 10th centuries at unknown German monastery. The two most important texts, the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae and the Itinerarium Urbis Romae, were composed in Rome in the early 9th century. The author is known today as the Anonymous of Einsiedeln because the only surviving copy of his work is located in the Stiftbibliothek; the author had no connection to the Swiss monastery. The Einsiedeln texts were redacted by a northern scribe in a clearly-legible Caroline miniscule, from either a German or Italian manuscript source.

TheItinerarium (fols. 79v-89r) is a topographical guide to the principal monuments of the city. Composed for pilgrims visiting the city, the text consists of a series of walks across the city beginning and ending at different city gates. Both pagan and Christian monuments are indicated. For most monuments, the text is only list of names with no descriptions. Many of those casually mentioned names—Theatrum Pompei, Septizonium, Thermae Traiani, Capitolium—however, grip the modern reader’s attention, reminding him/her of how many major monuments of which no trace remains today, were still standing and correctly identified in the Carolingian period.

The itinareries are accompanied by the Inscriptiones Urbis Romae (67r-79v). This collection records epigraphic inscriptions seen on bridges, temples, arches, baths, basilicae, column and statue bases, and so on. As the majority of those monuments no longer survive, the Einsiedeln transcriptions are of vital importance to any understanding of ancient Roman topography, imperial patronage, and architectural and urban history. In the few cases where the source of a redaction by the Anonymous still exists, his transcritions have proved to be accurate.

Given its usefulness, the text must have been popular among foreign visitors to Rome. The Einsiedeln manuscript however, is the only known copy of the ItinerariumandInscriptiones.Although the volume had entered the library’s collection in the 17th century, those texts were “discovered” and correctly identified only in the 19th century.

Just watched Pilgrimage with @eggscargo and it was really good!! Closed my eyes for the gorey bits though oof

Medieval souvenirs

Thin pieces of metal that are bluntly attached to precious illuminated pages. It is not something you see every day in a medieval book - or imagined to see at all in such delicate objects. They are pilgrim’s badges, mementos purchased during pilgrimages to holy sites in medieval Europe. They are really not very different from the Eiffel Towers, baseball caps or Big Bens that we carry home in our suitcases today: they are mass-produced, cheap and highly portable souvenirs. If you went to see the shrine of St Thomas Becket, you would take a badge home, partly to show that you had been (like this one). The badges above are special because the pilgrim attached them to the pages of his prayerbook when he came home, which is how they survived. The shiny pieces of metal are religious instruments, of course, but they also proudly emphasize that the owner of the book went on a real pilgrimage: been there, done that!

Pics: Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce MS 51 (Book of Hours, Flanders, c. 1490). More images and information here. More about medieval pilgrimages here. A safer (but not cheaper) alternative was to have pilgrim’s badges painted into a book (here).

Post link

Princess Grace of Monaco and her son, Prince Albert, on the pilgrimage to Lourdes, July 3, 1979.

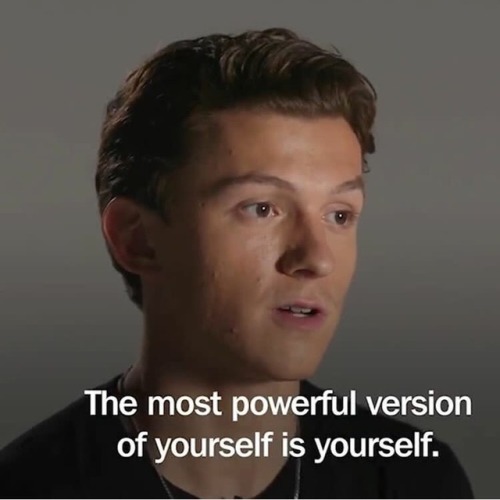

Cause if you’re gonna be cute might as well be a good role model too, huh? gosh darn tom you’re murdering me.

Post link

Tom doing ballet cause he’s cute af

Tom talking about breaking his nose! (which explains the slight crook)