#poem-a-day

Today, enjoy this audiogram of a poem by Catherine Cohen, a comedian and performer whose speaking voice—hot with self-critique and snark, and just a smidge of tenderness when she can’t take herself anymore—is perfectly suited to her verses.

poem I wrote after I tried to write a tweet about sparkling water

I’ve got a disease where I haven’t watched

an entire feature film since the aughts

do you like how I said “aughts”?

you don’t see that every day!

I’ve never been to a sex party

but one time I made fun of this girl

for bringing deviled eggs to an event

and then I ate six of them.

humiliation, satisfaction,

a long walk home in spring.

I love sex and I love before it—

the double vodka soda leg touch

Is it possible to miss everything at once?

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about God I Feel Modern Tonight by Catherine Cohen, also available as an audiobook read by the author.

- Learn more about Catherine Cohen.

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

With April comes the Knopf Poem-a-Day newsletter, a tradition since the late 1990s. Look out for a poem in your inbox each and every day of poetry month—and in the meantime, enjoy a taste of spring in these lines from Jill Bialosky’s book-length lyric sequence, Asylum.

& then we laughed so hard—what else could we do—

we scared the birds. We kept coming back, knowing

the flap of a butterfly wing, for instance, ripple of a storm,

invisible society of connected roots beneath the ground

(if you break one, you break the other) could change everything.

Thank you for reading and listening and watching—for being part of our community—throughout this month. With final good wishes for the health of all, here is Frank O'Hara (1926-1966), one of the presiding spirits of Knopf Poetry for his generosity on the page, his pursuit of beauty in its myriad forms, his boundless sense of adventure and of literature’s possibilities. May soft banks enfold you until we meet again over a poem.

River

Whole days would go by, and later their years,

while I thought of nothing but its darkness

drifting like a bridge against the sky.

Day after day I dreamily sought its melancholy,

its searchings, its soft banks enfolded me,

and upon my lengthening neck its kiss

was murmuring like a wound. My very life

became the inhalation of its weedy ponderings

and sometimes in the sunlight my eyes,

walled in water, would glimpse the pathway

to the great sea. For it was there I was being borne.

Then for a moment my strengthening arms

would cry out upon the leafy crest of the air

like whitecaps, and lightning, swift as pain,

would go through me on its way to the forest,

and I’d sink back upon that brutal tenderness

that bore me on, that held me like a slave

in its liquid distances of eyes, and one day,

though weeping for my caresses, would abandon me,

moment of infinitely salty air! sun fluttering

like a signal! upon the open flesh of the world.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Selected Poems by Frank O'Hara, edited by Mark Ford

- Learn more about Frank O'Hara

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

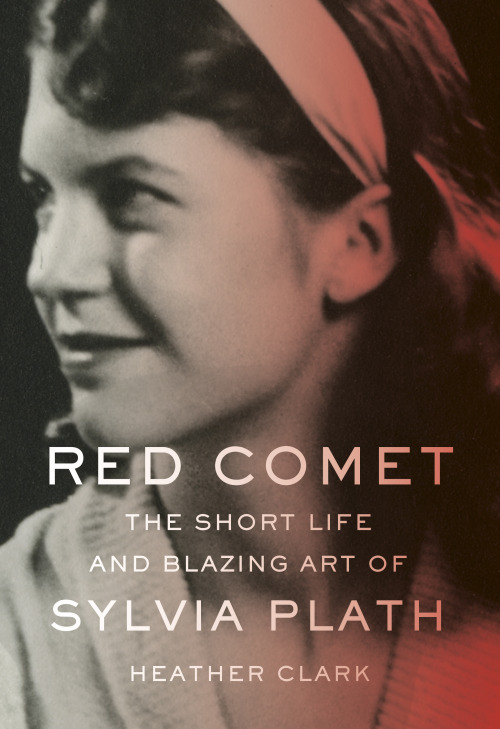

Today we present a preview of a major new biography of Sylvia Plath, Red Comet, coming this fall. Through committed investigative scholarship, Heather Clark is able to offer the most extensively researched and nuanced view yet of a poet whose influence grows with each new generation of readers. Clark is the first biographer to draw upon all of Plath’s surviving letters, including fourteen newly discovered letters Plath sent to her psychiatrist in 1961-63, and to draw extensively on her unpublished diaries, calendars, and poetry manuscripts. She is also the first to have had full, unfettered access to Ted Hughes’s unpublished diaries and poetry manuscripts, allowing her to present a balanced and humane view of this remarkable creative marriage (and its unravelling) from both sides. She is able to present significant new findings about Plath’s whereabouts and her state of health on the weekend leading up to her death. With these and many other “firsts,” Clark’s approach to Plath is to chart the course of this brilliant poet’s development, highlighting her literary and intellectual growth rather than her undoing. Here, we offer a passage from Clark’s prologue to the biography, followed by lines from one of Plath’s celebrated “bee poems.”

fromRed Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath

The Oxford professor Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf’s biographer, has written, “Women writers whose lives involved abuse, mental-illness, self-harm, suicide, have often been treated, biographically, as victims or psychological case-histories first and as professional writers second.” This is especially true of Sylvia Plath, who has become cultural shorthand for female hysteria. When we see a female character reading The Bell Jar in a movie, we know she will make trouble. As the critic Maggie Nelson reminds us, “to be called the Sylvia Plath of anything is a bad thing.” Nelson reminds us, too, that a woman who explores depression in her art isn’t perceived as “a shamanistic voyager to the dark side, but a ‘madwoman in the attic,’ an abject spectacle.” Perhaps this is why Woody Allen teased Diane Keaton for reading Plath’s seminal collection Ariel in Annie Hall. Or why, in the 1980s, a prominent reviewer cracked his favorite Plath joke as he reviewed Plath’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Collected Poems: “ ‘Why did SP cross the road?’ ‘To be struck by an oncoming vehicle.’ ” Male writers who kill themselves are rarely subject to such black humor: there are no dinner-party jokes about David Foster Wallace.

Since her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath has become a paradoxical symbol of female power and helplessness whose life has been subsumed by her afterlife. Caught in the limbo between icon and cliché, she has been mythologized and pathologized in movies, television, and biographies as a high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death. These distortions gained momentum in the 1960s when Ariel was published. Most reviewers didn’t know what to make of the burning, pulsating metaphors in poems like “Lady Lazarus” or the chilly imagery of “Edge.” Time called the book a “jet of flame from a literary dragon who in the last months of her life breathed a burning river of bale across the literary landscape.” The Washington Post dubbed Plath a “snake lady of misery” in an article entitled “The Cult of Plath.” Robert Lowell, in his introduction to Ariel, characterized Plath as Medea, hurtling toward her own destruction.

Recent scholarship has deepened our understanding of Plath as a master of performance and irony. Yet the critical work done on Plath has not sufficiently altered her popular, clichéd image as the Marilyn Monroe of the literati. Melodramatic portraits of Plath as a crazed poetic priestess are still with us. Her most recent biographer called her “a sorceress who had the power to attract men with a flash of her intense eyes, a tortured soul whose only destiny was death by her own hand.” He wrote that she “aspired to transform herself into a psychotic deity.” These caricatures have calcified over time into the popular, reductive version of Sylvia Plath we all know: the suicidal writer of The Bell Jar whose cultish devotees are black-clad young women. (“Sylvia Plath: The Muse of Teen Angst,” reads the title of a 2003 article in Psychology Today.) Plath thought herself a different kind of “sorceress”: “I am a damn good high priestess of the intellect,” she wrote her friend Mel Woody in July 1954.

Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote of Sylvia Plath, “when the curtain goes down, it is her own dead body there on the stage, sacrificed to her own plot.” Yet to suggest that Plath’s suicide was some sort of grand finale only perpetuates the Plath myth that simplifies our understanding of her work and her life. Sylvia Plath was one of the most highly educated women of her generation, an academic superstar and perennial prizewinner. Even after a suicide attempt and several months at McLean Hospital, she still managed to graduate from Smith College summa cum laude. She was accepted to graduate programs in English at Columbia, Oxford, and Radcliffe and won a Fulbright Fellowship to Cambridge, where she graduated with high honors. She was so brilliant that Smith asked her to return to teach in their English department without a PhD. Her mastery of English literature’s past and present intimidated her students and even her fellow poets. In Robert Lowell’s 1959 creative writing seminar, Plath’s peers remembered how easily she picked up on obscure literary allusions. “ ‘It reminds me of Empson,’ Sylvia would say … ‘It reminds me of Herbert.’ ‘Perhaps the early Marianne Moore?’ ” Later, Plath made small talk with T. S. Eliot and Stephen Spender at London cocktail parties, where she was the model of wit and decorum.

Very few friends realized that she struggled with depression, which revealed itself episodically. In college, she aced her exams, drank in moderation, dressed sharply, and dated men from Yale and Amherst. She struck most as the proverbial golden girl. But when severe depression struck, she saw no way out. In 1953, a depressive episode led to botched electroshock therapy sessions at a notorious asylum. Plath told her friend Ellie Friedman that she had been led to the shock room and “electrocuted.” “She told me that it was like being murdered, it was the most horrific thing in the world for her. She said, ‘If this should ever happen to me again, I will kill myself.’ ” Plath attempted suicide rather than endure further tortures.

In 1963, the stressors were different. A looming divorce, single motherhood, loneliness, illness, and a brutally cold winter fueled the final depression that would take her life. Plath had been a victim of psychiatric mismanagement and negligence at age twenty, and she was terrified of depression’s “cures,” as she wrote in her last letter to her psychiatrist—shock treatment, insulin injections, institutionalization, “a mental hospital, lobotomies.” It is no accident that Plath killed herself on the day she was supposed to enter a British psychiatric ward.

Sylvia Plath did not think of herself as a depressive. She considered herself strong, passionate, intelligent, determined, and brave, like a character in a D. H. Lawrence novel. She was tough-minded and filled her journal with exhortations to work harder—evidence, others have said, of her pathological, neurotic perfectionism. Another interpretation is that she was—like many male writers—simply ambitious, eager to make her mark on the world. She knew that depression was her greatest adversary, the one thing that could hold her back. She distrusted psychiatry—especially male psychiatrists—and tried to understand her own depression intellectually through the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, Erich Fromm, and others. Self-medication, for Plath, meant analyzing the idea of a schizoid self in her honors thesis on The Brothers Karamazov.

Bitter experience taught her how to accommodate depression—exploit it, even—in her art. “There is an increasing market for mental-hospital stuff. I am a fool if I don’t relive, or recreate it,” she wrote in her journal. The remark sounds trite, but her writing on depression was profound. Her own immigrant family background and experience at McLean gave her insight into the lives of the outcast. Plath would fill her late work, sometimes controversially, with the disenfranchised—women, the mentally ill, refugees, political dissidents, Jews, prisoners, divorcées, mothers. As she matured, she became more determined to speak out on their behalf. In The Bell Jar, one of the greatest protest novels of the twentieth century, she probed the link between insanity and repression. Like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the novel exposed a repressive Cold War America that could drive even the “best minds” of a generation crazy. Are you really sick, Plath asks, or has your society made you so? She never romanticized depression and death; she did not swoon into darkness. Rather, she delineated the cold, blank atmospherics of depression, without flinching. Plath’s ability to resurface after her depressive episodes gave her courage to explore, as Ted Hughes put it, “psychological depth, very lucidly focused and lit.” The themes of rebirth and renewal are as central to her poems as depression, rage, and destruction.

“What happens to a dream deferred?” Langston Hughes asked in his poem “Harlem.” Did it “crust and sugar over—/ like a syrupy sweet?” For most women of Plath’s generation, it did. But Plath was determined to follow her literary vocation. She dreaded the condescending label of “lady poet,” and she had no intention of remaining unmarried and childless like Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop. She wanted to be a wife, mother, and poet—a “triple-threat woman,” as she put it to a friend. These spheres hardly ever overlapped in the sexist era in which she was trapped, but for a time, she achieved all three goals.

They thought death was worth it, but I

Have a self to recover, a queen.

Is she dead, is she sleeping?

Where has she been,

With her lion-red body, her wings of glass?

Now she is flying More terrible than she ever was, red

Scar in the sky, red comet

Over the engine that killed her—

The mausoleum, the wax house.

from “Stings” by Sylvia Plath

More on this book and author:

- Learn more aboutRed Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plathby Heather Clark

- Learn more about Heather Clark

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

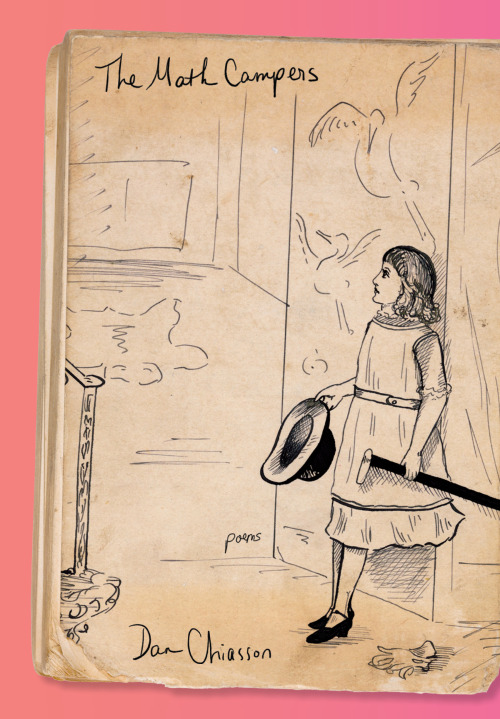

Dan Chiasson’s The Math Campers, to come this fall, is a book in part about fatherhood and adolescence—his own, his kids’, and the new freedoms as well as existential threats that shape their world. Today’s poem, from a multipart piece entitled “Over & Over,” is dedicated to his sons.

from “Over & Over”

my awareness seems to extend this day

past the trap my body set for me

past its small, pitiful adjustments

of head here wings here antennae here

what does it matter, the head and wings

and antennae if my awareness

soars over the tops of the pines

with their spiny flowers still green

like a drone flown by a teenage pilot

over the rooftops, silent yawp

past near meadows over the stop and shop

its dragonfly landing gear ready

now it zooms in on the roots which grip

the soil and feed on its decay

your hand and mine at the same angle

you there, in the future, fleeing me

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Dan Chiasson’s forthcoming collection, The Math Campers

- Browse other books by Dan Chiasson and catch up with him on Twitter, @dchiasso

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

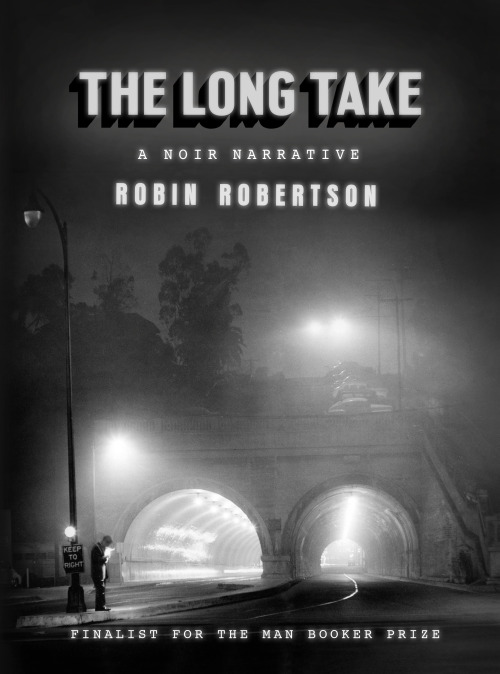

In these excerpts from the pages of Robin Robertson’s prize-winning The Long Take, soon to be published in paperback, we see New York City in 1946 through the eyes of Walker, a Nova Scotian D-Day veteran just landing on our shores. The book goes on to tell his story, as he makes his way west to become a journalist in Los Angeles, in the heyday of film noir.

from The Long Take

And there it was: the swell

and glitter of it like a standing wave –

the fabled, smoking ruin, the new towers rising

through the blue,

the ranked array of ivory and gold, the glint,

the glamour of buried light

as the world turned round it

very slowly

this autumn morning, all amazed.

And it stayed there, watching,

as they made toward it,

the truck-driver and the young man,

under pylons, wires, utility poles,

past warehouses, container parks,

deserted lots, between the long

oily marshes, landfill sites and swamps,

before slipping down

under the Hudson, and coming up

on the other side

to find a black wetness

of streets trashed and empty

and the city gone.

‘Try the docks. They can always use men.’

*

At night, the river rolls and turns like oil

under the bridges,

in through the slips.

He walked for hours –

following the glow

in the sky uptown he’d been told

was the lights of Times Square –

his shadow moving with him

below the street-lamps: dense, tight,

very black and sharp, foreshortened, but already

starting to lengthen as he goes, attenuating

to a weak stain. Then back in

under another streetlight, shadow

darkening again, clean and hard.

Who he really is, or was,

lies somewhere in between.

*

In the last splinter of sunlight allowed between the skyscrapers

an old lady is sitting with a book,

moving her chair every quarter of an hour

a little farther down the alleyway.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about The Long Take by Robin Robertson

- Learn more about Robin Robertson

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

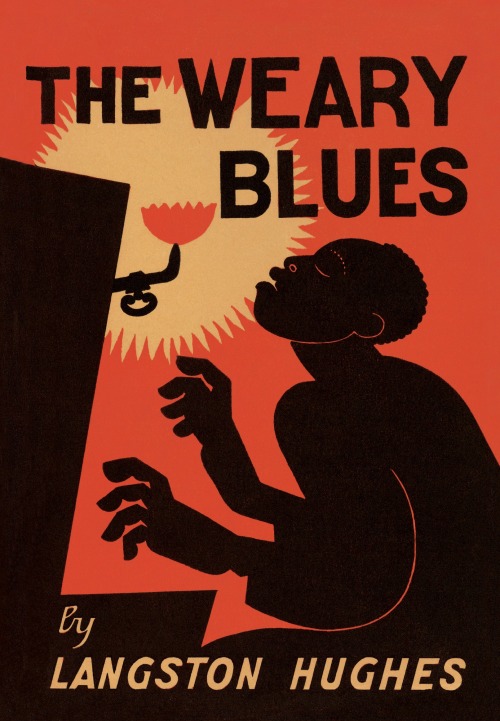

From the heart of a young Langston Hughes.

Poem

The night is beautiful.

So the faces of my people.

The stars are beautiful,

So the eyes of my people.

Beautiful, also, is the sun.

Beautiful, also, are the souls of my people.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about The Weary Blues by Langston Hughes

- Browse other books by Langston Hughes

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

In the work of Mark Strand (1934–2015), desolation and isolation come to have their own cadence — one of timelessness, acceptance, and even sly comfort extended to the reader. (This classic, known by heart to Strand’s fans, seemed to call out for a broadside.)

A Piece of the Storm

From the shadow of domes in the city of domes,A snowflake, a blizzard of one, weightless, entered your room

And made its way to the arm of the chair where you, looking up

From your book, saw it the moment it landed. That’s all

There was to it. No more than a solemn waking

To brevity, to the lifting and falling away of attention, swiftly,

A time between times, a flowerless funeral. No more than that

Except for the feeling that this piece of the storm,

Which turned into nothing before your eyes, would come back,

That someone years hence, sitting as you are now, might say:

“It’s time. The air is ready. The sky has an opening.”

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Collected Poems by Mark Strand.

- Browse other books by Mark Strand.

- Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

Post link

How we interact with our climate and nature, for good and too often for ill, is a pressing concern in the work of Jane Hirshfield, as in this piece from her latest collection, Ledger.

Corals, Coho, Coelenterates

I keep a white page before me.

Each time one

is marred with effort, striving, effect, I turn to another.

Corals, coho, coelenterates

inside the waving arms of your branches

that give off a scent intoxicant only to certain fish—

lichens, burdocks, mycelial mats between trees—

forgive this hubris.

Some hope is in it.

Your companions are new here.

A child who crayons does not know

her drawing leaves behind absence on forest, on ocean.

She falls into the colors.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Ledger by Jane Hirshfield.

- Browse other books by Jane Hirshfield.

- Hear Jane Hirshfield read in person and online in Newtown, PA (Wordsmiths Reaing Series, April 29).

- Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

Post link

In the “Other Countries” section of her now classic collection My Wicked Wicked Ways, Sandra Cisneros pens lines from Venice, Paris, Trieste, the old market in Antibes, the Greek island of Hydra in pouring rain, and Sarajevo, as below.

Peaches—Six in a Tin Bowl, Sarajevo

If peaches had armssurely they would hold one another

in their peach sleep.

And if peaches had feet

it is sure they would

nudge one another

with their soft peachy feet.

And if peaches could

they would sleep

with their dimpled head

on the other’s

each to each.

Like you and me.

And sleep and sleep.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about My Wicked Wicked Ways by Sandra Cisneros, and follow her on Instagram (@officialsandracisneros).

- Browse other books by Sandra Cisneros, including her forthcoming Martita, I Remember You / Martita te recuerdo, to be published in a dual-language edition translated by Liliana Valenzuela.

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

Post link

an obstacle

they said of the mountain

its white peak piercing

moonlit tapestry trembled

against the stone,

their complaints nothing but twigs

in feasting campfire.

-the mountain, Kelsey Ray Banerjee

Today my poem “Feast Green and Stained” is part of The Academy of American Poets’ “Poem-a-Day” series. My sincerest gratitude to guest editor Don Mee Choi! Thanks also to Francisco Márquez and everyone else involved!

Post link