#poetry month

REFUSAL TO MOURN

In lieu of

flowers, send

him back.

ANDREA COHEN

ANDREA COHEN

ARROW

There will be loss so great it will divide the gods up into teams. And the horses. The ones that could kill you, the ones that killed us, are making their way across the green river, that’s how cold. That’s how serious. You won’t remember because the light is soft. & the trees. & your son will say the moon. & your daughter will say Venus. & the baby baby of every song on the radio. & a horse will walk up to the locked gate. & a horse will eye your car. & a man will say careful honey. & you will throw your head back and touch the cross you wear. & he will say careful honey & you will pull back the bowstring at full draw. & he will say careful honey & you run the wind at her own game & have now. Let go.

KATHERINE OSBORNE

IN THE BAD DAYS

I am writing to you

from deep in the bad days,hoping you will hear me

wherever you are,far away in a better time —

+

In a better time,

hoping you will hear me,

far away,

wherever you are:

I came upon a heron

late at night,deep in these bad days.

+

Late tonight,

deep in our bad days,

he plucked a frog from the waterfilled ditch.

His eye

was black glass. I am writing

to you,

wherever you are

+

late in my bad days.

The frog’s neck

was broken,

so its legs dangled.

The heron eyed me

blackly

from the wet ditch.

I am writing to you

+

from deep in the black days.

The dead

dangled.

I watched from the sidewalk.

The heron’s glass eye

eyed me

in the streetlight’s glare.

Wherever you are

+

in a better time:

people were dying.

I am writing to tell you

people are dying.

Remember that

while you tie your shoes

to go for your walk

through the song-filled

night,

through the beautiful night

of another time.

KEVIN PRUFER

NEST

And then there came a day that was a day

a world of my wanting with you in it

and all the small creatures came to our side

mewing and cheeping as small creatures do

a day I had wanted for a long time

a small-creature hour in the life of our day

where there were many places to lie down

and sigh and sleep and cogitate and hug

a huge happening among the small lives

a little cuddle with a dream in it

a coddled egg an apron with a bib

a nest for nourishing the ragged nerves

O robin O rabbit O bat O tiny vole

all flyers and burrowers come to us now

through our heat ducts and tear ducts and chimneys

come to us with your small-world intentions

that place where only we know how to live

where no one else knows what we say and do

no one knows the crumbs or the flies we eat

or the silly songs we hum as we sleep

SARAH ARVIO

ATLIEN FREESTYLES OVER “WHEELZ OF STEEL”

Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.

—Toni Morrison

A paralytic sickness bias white flame burning thru red & blue cells

A ring around the revolver barrel roulette wheelz Russian clan-

destine war imagined happened & thus foreseeable Moral schism

hard for them to swallow as cod liver oil: filet mignon backmasked: rods &

cotton scalps & cod Give a woman a fish & watch her envision an end

to famine [which is the beginning of living upright] Teach a man to fish

a market & he will lure you w/ the chummy glint of an iced out life as he

guts your public for trophies Do check for trout lips at mention of any

“system” | counter- clockwise prison built to omit marrow in its

trappings E.g. shackles into handcuffs into plantation industries

into wireless tethers into “job growth” Landlord says raining dollar bills

where i hear bills dollar raining When i say precipitous one of us pictures

a cliff though we share the same broken elevator pulley- steel eyez

If only in the beginning someone said i wish us both to do more than survive

MARCUS WICKER

I’M SORRY

I want to apologize. I’m sorry that I have had to pull you down with me into this antechamber full of cold blood bags. It’s hard to believe such a room exists, that there is really a room where they just put bags of blood. But they stack up and stack up. When I got here, they didn’t cover the door, but they do now. I don’t think anyone ever comes for the blood bags again. No, really. It’s drafty. I’m so sorry.

Hold one of the bags, and feel the blood inside.

This is my mothering instinct talking.

I’m sorry for how this ends, in a chamber that used to lead somewhere.

NIINA POLLARI

NOT EVERYTHING IS A POEM

or has a poem inside it, but god help me

if I can’t find one when I empty

my son’s pockets before I do

the wash: one acorn, two rocks

(one smooth and gray, one rough

and glittering, flecked pink),

a chunk of mulch, a wilted

dandelion. The poem is there,

I think, pressing itself against

the grit or splinter or bitter

yellow, but I question its mother-

softness, suspicious of flowers

and laundry. I swear I’ve seen

poems riding my boy’s back

as he runs around our weed patch

of a lawn, letting crabgrass

saw his ankles because killing it

would mean killing the wild

violets, his sister’s namesakes.

I don’t dare look for poems

in spring even if all the purple

and green are on clearance then.

Two springs ago, my son

was so ill, he smelled bad-sweet,

and one morning he woke

shitting blood, saying my name,

my name, my name. No poem

kept his body from bruising

purple that would fade to green,

his skin a field of flowers—

no, not this poem and not

a poem at all. But he lived.

It’s spring again and he lives.

It’s spring again and his pockets

are full of petals and stones.

MAGGIE SMITH

CITY LAKE

Almost dusk. Fishermen packing up their bait,

a small girl singing there’s nothing in here nothing in here

casting a yellow pole, glancing at her father.

What is it they say about mercy? Five summers ago

this lake took a child’s life. Four summers

ago it saved mine, the way the willows stretch

toward the water but never kiss it, how people laugh

as they walk the concrete path or really have it out

with someone they love. One spring the path teemed

with baby frogs, so many flattened, so many jumping.

I didn’t know a damn thing then. I thought I was waiting

for something to happen. I stepped carefully

over the dead frogs and around the live ones.

What was I waiting for? Frogs to rain from the sky?

A great love? The little girl spies a perch

just outside her rod’s reach. She wants to wade in.

She won’t catch the fish and even if she does

it might be full of mercury. Still, I want her

to roll up her jeans and step into the water,

tell her it’s mercy, not mud, filling each impression

her feet make. I’m not saying she should

be grateful to be alive. I’m saying mercy

is a big dark lake we’re all swimming in.

CHELSEA DESAUTELS

SECOND ESTRANGEMENT

Please raise your hand,

whomever else of you

has been a child,

lost, in a market

or a mall, without

knowing it at first, following

a stranger, accidentally

thinking he is yours,

your family or parent, even

grabbing for his hands,

even calling the word

you said then for “Father,”

only to see the face

look strangely down, utterly

foreign, utterly not the one

who loves you, you

who are a bird suddenly

stunned by the glass partitions

of rooms.

How far

the world you knew, & tall,

& filled, finally, with strangers.

ARACELIS GIRMAY

ICYMI, our new partnership with Manual Cinema in honor of 100 years since the end of World War I is here! Three World War I Poems brings a selection of poems to life with innovative paper puppetry and animation work, each vignette sharing a different experience of “the war to end all wars” from a soldier’s point of view.

[video: Three interwoven vignettes of interpretations of “The Owl” by Edward Thomas, “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen, and “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae.]

In the second installment of Word: Collected Poetry Trace DePass contemplates how poetry can entrap, rather than release, past traumas and hardships. Filmed on location at Kenkeleba House Garden in the East Village.

[[Video: An exploration of the Kenkeleba House Garden, an outdoor green space in New York City filled with sculptures by African-American artists, the film begins by coming through the front gate and panning around to view a person (Trace DePass) sitting in the garden, then at the various installations in it. This happens throughout the film, interspersed with shots of the life happening in the neighborhood outside the garden and Trace interacting with the space. The film returns several times to a realistic metal sculpture of a man standing, his next straining to one side and a more abstract sculpture of a figure made out of metal and blue glass.]]

Thank you for reading and listening and watching—for being part of our community—throughout this month. With final good wishes for the health of all, here is Frank O'Hara (1926-1966), one of the presiding spirits of Knopf Poetry for his generosity on the page, his pursuit of beauty in its myriad forms, his boundless sense of adventure and of literature’s possibilities. May soft banks enfold you until we meet again over a poem.

River

Whole days would go by, and later their years,

while I thought of nothing but its darkness

drifting like a bridge against the sky.

Day after day I dreamily sought its melancholy,

its searchings, its soft banks enfolded me,

and upon my lengthening neck its kiss

was murmuring like a wound. My very life

became the inhalation of its weedy ponderings

and sometimes in the sunlight my eyes,

walled in water, would glimpse the pathway

to the great sea. For it was there I was being borne.

Then for a moment my strengthening arms

would cry out upon the leafy crest of the air

like whitecaps, and lightning, swift as pain,

would go through me on its way to the forest,

and I’d sink back upon that brutal tenderness

that bore me on, that held me like a slave

in its liquid distances of eyes, and one day,

though weeping for my caresses, would abandon me,

moment of infinitely salty air! sun fluttering

like a signal! upon the open flesh of the world.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Selected Poems by Frank O'Hara, edited by Mark Ford

- Learn more about Frank O'Hara

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

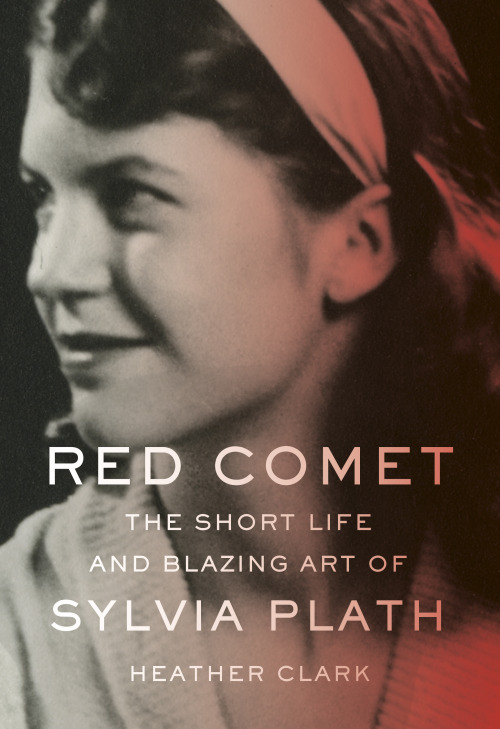

Today we present a preview of a major new biography of Sylvia Plath, Red Comet, coming this fall. Through committed investigative scholarship, Heather Clark is able to offer the most extensively researched and nuanced view yet of a poet whose influence grows with each new generation of readers. Clark is the first biographer to draw upon all of Plath’s surviving letters, including fourteen newly discovered letters Plath sent to her psychiatrist in 1961-63, and to draw extensively on her unpublished diaries, calendars, and poetry manuscripts. She is also the first to have had full, unfettered access to Ted Hughes’s unpublished diaries and poetry manuscripts, allowing her to present a balanced and humane view of this remarkable creative marriage (and its unravelling) from both sides. She is able to present significant new findings about Plath’s whereabouts and her state of health on the weekend leading up to her death. With these and many other “firsts,” Clark’s approach to Plath is to chart the course of this brilliant poet’s development, highlighting her literary and intellectual growth rather than her undoing. Here, we offer a passage from Clark’s prologue to the biography, followed by lines from one of Plath’s celebrated “bee poems.”

fromRed Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath

The Oxford professor Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf’s biographer, has written, “Women writers whose lives involved abuse, mental-illness, self-harm, suicide, have often been treated, biographically, as victims or psychological case-histories first and as professional writers second.” This is especially true of Sylvia Plath, who has become cultural shorthand for female hysteria. When we see a female character reading The Bell Jar in a movie, we know she will make trouble. As the critic Maggie Nelson reminds us, “to be called the Sylvia Plath of anything is a bad thing.” Nelson reminds us, too, that a woman who explores depression in her art isn’t perceived as “a shamanistic voyager to the dark side, but a ‘madwoman in the attic,’ an abject spectacle.” Perhaps this is why Woody Allen teased Diane Keaton for reading Plath’s seminal collection Ariel in Annie Hall. Or why, in the 1980s, a prominent reviewer cracked his favorite Plath joke as he reviewed Plath’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Collected Poems: “ ‘Why did SP cross the road?’ ‘To be struck by an oncoming vehicle.’ ” Male writers who kill themselves are rarely subject to such black humor: there are no dinner-party jokes about David Foster Wallace.

Since her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath has become a paradoxical symbol of female power and helplessness whose life has been subsumed by her afterlife. Caught in the limbo between icon and cliché, she has been mythologized and pathologized in movies, television, and biographies as a high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death. These distortions gained momentum in the 1960s when Ariel was published. Most reviewers didn’t know what to make of the burning, pulsating metaphors in poems like “Lady Lazarus” or the chilly imagery of “Edge.” Time called the book a “jet of flame from a literary dragon who in the last months of her life breathed a burning river of bale across the literary landscape.” The Washington Post dubbed Plath a “snake lady of misery” in an article entitled “The Cult of Plath.” Robert Lowell, in his introduction to Ariel, characterized Plath as Medea, hurtling toward her own destruction.

Recent scholarship has deepened our understanding of Plath as a master of performance and irony. Yet the critical work done on Plath has not sufficiently altered her popular, clichéd image as the Marilyn Monroe of the literati. Melodramatic portraits of Plath as a crazed poetic priestess are still with us. Her most recent biographer called her “a sorceress who had the power to attract men with a flash of her intense eyes, a tortured soul whose only destiny was death by her own hand.” He wrote that she “aspired to transform herself into a psychotic deity.” These caricatures have calcified over time into the popular, reductive version of Sylvia Plath we all know: the suicidal writer of The Bell Jar whose cultish devotees are black-clad young women. (“Sylvia Plath: The Muse of Teen Angst,” reads the title of a 2003 article in Psychology Today.) Plath thought herself a different kind of “sorceress”: “I am a damn good high priestess of the intellect,” she wrote her friend Mel Woody in July 1954.

Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote of Sylvia Plath, “when the curtain goes down, it is her own dead body there on the stage, sacrificed to her own plot.” Yet to suggest that Plath’s suicide was some sort of grand finale only perpetuates the Plath myth that simplifies our understanding of her work and her life. Sylvia Plath was one of the most highly educated women of her generation, an academic superstar and perennial prizewinner. Even after a suicide attempt and several months at McLean Hospital, she still managed to graduate from Smith College summa cum laude. She was accepted to graduate programs in English at Columbia, Oxford, and Radcliffe and won a Fulbright Fellowship to Cambridge, where she graduated with high honors. She was so brilliant that Smith asked her to return to teach in their English department without a PhD. Her mastery of English literature’s past and present intimidated her students and even her fellow poets. In Robert Lowell’s 1959 creative writing seminar, Plath’s peers remembered how easily she picked up on obscure literary allusions. “ ‘It reminds me of Empson,’ Sylvia would say … ‘It reminds me of Herbert.’ ‘Perhaps the early Marianne Moore?’ ” Later, Plath made small talk with T. S. Eliot and Stephen Spender at London cocktail parties, where she was the model of wit and decorum.

Very few friends realized that she struggled with depression, which revealed itself episodically. In college, she aced her exams, drank in moderation, dressed sharply, and dated men from Yale and Amherst. She struck most as the proverbial golden girl. But when severe depression struck, she saw no way out. In 1953, a depressive episode led to botched electroshock therapy sessions at a notorious asylum. Plath told her friend Ellie Friedman that she had been led to the shock room and “electrocuted.” “She told me that it was like being murdered, it was the most horrific thing in the world for her. She said, ‘If this should ever happen to me again, I will kill myself.’ ” Plath attempted suicide rather than endure further tortures.

In 1963, the stressors were different. A looming divorce, single motherhood, loneliness, illness, and a brutally cold winter fueled the final depression that would take her life. Plath had been a victim of psychiatric mismanagement and negligence at age twenty, and she was terrified of depression’s “cures,” as she wrote in her last letter to her psychiatrist—shock treatment, insulin injections, institutionalization, “a mental hospital, lobotomies.” It is no accident that Plath killed herself on the day she was supposed to enter a British psychiatric ward.

Sylvia Plath did not think of herself as a depressive. She considered herself strong, passionate, intelligent, determined, and brave, like a character in a D. H. Lawrence novel. She was tough-minded and filled her journal with exhortations to work harder—evidence, others have said, of her pathological, neurotic perfectionism. Another interpretation is that she was—like many male writers—simply ambitious, eager to make her mark on the world. She knew that depression was her greatest adversary, the one thing that could hold her back. She distrusted psychiatry—especially male psychiatrists—and tried to understand her own depression intellectually through the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, Erich Fromm, and others. Self-medication, for Plath, meant analyzing the idea of a schizoid self in her honors thesis on The Brothers Karamazov.

Bitter experience taught her how to accommodate depression—exploit it, even—in her art. “There is an increasing market for mental-hospital stuff. I am a fool if I don’t relive, or recreate it,” she wrote in her journal. The remark sounds trite, but her writing on depression was profound. Her own immigrant family background and experience at McLean gave her insight into the lives of the outcast. Plath would fill her late work, sometimes controversially, with the disenfranchised—women, the mentally ill, refugees, political dissidents, Jews, prisoners, divorcées, mothers. As she matured, she became more determined to speak out on their behalf. In The Bell Jar, one of the greatest protest novels of the twentieth century, she probed the link between insanity and repression. Like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the novel exposed a repressive Cold War America that could drive even the “best minds” of a generation crazy. Are you really sick, Plath asks, or has your society made you so? She never romanticized depression and death; she did not swoon into darkness. Rather, she delineated the cold, blank atmospherics of depression, without flinching. Plath’s ability to resurface after her depressive episodes gave her courage to explore, as Ted Hughes put it, “psychological depth, very lucidly focused and lit.” The themes of rebirth and renewal are as central to her poems as depression, rage, and destruction.

“What happens to a dream deferred?” Langston Hughes asked in his poem “Harlem.” Did it “crust and sugar over—/ like a syrupy sweet?” For most women of Plath’s generation, it did. But Plath was determined to follow her literary vocation. She dreaded the condescending label of “lady poet,” and she had no intention of remaining unmarried and childless like Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop. She wanted to be a wife, mother, and poet—a “triple-threat woman,” as she put it to a friend. These spheres hardly ever overlapped in the sexist era in which she was trapped, but for a time, she achieved all three goals.

They thought death was worth it, but I

Have a self to recover, a queen.

Is she dead, is she sleeping?

Where has she been,

With her lion-red body, her wings of glass?

Now she is flying More terrible than she ever was, red

Scar in the sky, red comet

Over the engine that killed her—

The mausoleum, the wax house.

from “Stings” by Sylvia Plath

More on this book and author:

- Learn more aboutRed Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plathby Heather Clark

- Learn more about Heather Clark

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

Dan Chiasson’s The Math Campers, to come this fall, is a book in part about fatherhood and adolescence—his own, his kids’, and the new freedoms as well as existential threats that shape their world. Today’s poem, from a multipart piece entitled “Over & Over,” is dedicated to his sons.

from “Over & Over”

my awareness seems to extend this day

past the trap my body set for me

past its small, pitiful adjustments

of head here wings here antennae here

what does it matter, the head and wings

and antennae if my awareness

soars over the tops of the pines

with their spiny flowers still green

like a drone flown by a teenage pilot

over the rooftops, silent yawp

past near meadows over the stop and shop

its dragonfly landing gear ready

now it zooms in on the roots which grip

the soil and feed on its decay

your hand and mine at the same angle

you there, in the future, fleeing me

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about Dan Chiasson’s forthcoming collection, The Math Campers

- Browse other books by Dan Chiasson and catch up with him on Twitter, @dchiasso

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

Post link

In the “Other Countries” section of her now classic collection My Wicked Wicked Ways, Sandra Cisneros pens lines from Venice, Paris, Trieste, the old market in Antibes, the Greek island of Hydra in pouring rain, and Sarajevo, as below.

Peaches—Six in a Tin Bowl, Sarajevo

If peaches had armssurely they would hold one another

in their peach sleep.

And if peaches had feet

it is sure they would

nudge one another

with their soft peachy feet.

And if peaches could

they would sleep

with their dimpled head

on the other’s

each to each.

Like you and me.

And sleep and sleep.

More on this book and author:

- Learn more about My Wicked Wicked Ways by Sandra Cisneros, and follow her on Instagram (@officialsandracisneros).

- Browse other books by Sandra Cisneros, including her forthcoming Martita, I Remember You / Martita te recuerdo, to be published in a dual-language edition translated by Liliana Valenzuela.

- Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

- To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

Post link

No place hosts foes like the soul does:

The soul’s a field on which all of the soldiers

Are pitched in a conflict of emotions,

The victor of which will control personas;

Some souls see more wars than others

Where Hope’s men fall in appalling numbers

And there’s a significant proportion of us

Wishing for a clear field, where all is summer…

Some souls see trauma suffered -

On these fields is the battle most passionate;

There’s Fear and Mistrust ganging up on Happiness -

They’re strong by themselves, lethal in aggregate -

Indifference looks on, inanimate

As Love shrugs off Doubt, gives Lust an uppercut

And Shame knifes Pride, letting out its blood and guts;

Seems the rule of this fight is ‘double up,

Be scheming, or else get squashed like butternut’…

My soul -

Was unquiet;

See, in there, Despair had run riot;

Frustration sent Hades one client

(He’d slain Patience), and Grace lay dying,

Hastened to grave by a shot from Jealousy

Who’d sniped her from the very top of the lemon tree…

Troops marches to Malice’s drumroll,

Advancing to castle where Joy was holed up,

Mourning the loss of Optimism, who Woe just

Dismembered and left as conducts for vultures;

Seemed they’d won the day, but their way

Was blocked at the gates by Hatred and Rage -

They knew, in this fable of Aesop,

That negatives need positives to feed off

So they advised these troops to ease off

But the closing part of the team-mates’ speech was:

‘Every now and then, we can’t keep the pressure up

On this soul, or it will be the death of us;

Too much violence will leave the soul crushed,

Since there’s a fine line between diamonds and coal-dust;

You know what? Let’s retreat for now;

Let’s allow Joy to hang out with Relief for now;

Let’s let this soul’s esteem be repaired -

But when we return, they’d better be prepared.’

- from ‘Eating Roses for Dinner’ (2015)

Musa Okwongae, photographed by Naomi Woddis