#armistice

Boston Post, Massachusetts, January 5, 1921

The Post’s famous feline (at left) and his former arch enemy, snapped by a Post photographer yesterday shortly after they had signed articles of peace and formed the League of Catdom. Hindy is to retain his title of Post Cat-In-Chief, and Tom will be his assistant.

Post link

Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow Nation, pictured at the burial of the Unknown Soldier. The sarcophagus familiar to modern visitors was not completed until 1931.

November 11 1921, Arlington–On Armistice Day 1920, the United Kingdom and France had both buried unknown soldiers in places of honor–the former in Westminster Abbey, the latter under the Arc de Triomphe. In 1921, the United States followed suit. An unknown soldier was transported back across the Atlantic from France, where he laid in state in the Capitol rotunda for two days. On Armistice Day, the same day that the peace treaty with Germany would finally enter into effect, the casket was at the front of a procession down Pennsylvania Avenue as far as the White House, followed on foot by President Harding and General Pershing.

Wilson in a carriage at the end of the procession down Pennsylvania Avenue.

At the end of the procession were Woodrow and Edith Wilson in a rented carriage. The New York World wrote that the “pale face of the man who gave his health and strength to uphold the same ideals for which the Unknown Soldier died seemingly unleashed the pent-up emotions of the watchers.” Wilson did not continue on to Arlington, due to a combination of his health concerns preventing him from climbing the stairs at the amphitheater there, and Harding’s desire not to be upstaged by his predecessor.

General Jacques of Belgium, General Diaz of Italy, Marshal Foch of France, General Pershing of the United States, and Admiral Beatty of the United Kingdom, pictures at the dedication of the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City on November 1.

At the service in Arlington, President Harding gave a brief speech. He was followed by General Jacques of Belgium, Admiral Beatty (who presented the Unknown Soldier with the Victoria Cross), Marshal Foch, and General Diaz. The four military men were at the end of a tour of the United States, along with General Pershing, which also included the groundbreaking of the Liberty Memorial (now the National World War I Memorial) in Kansas City on November 1. Also in attendance were a large number of foreign civilian notables, among them Arthur Balfour and French PM Briand, who were in Washington for the start of the Washington Naval Conference on arms limitation the next day.

The burial service ended with a brief statement by Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow Nation, the sounding of “Taps” on a bugle, and a twenty-one gun salute.

Sources include: Patricia O’Toole, The Moralist (includes image credit for the picture of Wilson).

A massive crowd rallies outside the former Royal Palace and the Kaiser Wilhelm Monument, expressing their support for the Republic. Both structures were demolished by the East German government after World War II, though a reconstruction of the palace was completed in 2020.

August 31 1921, Biberach–Matthias Erzberger, leading advocate of peace since July 1917 and signer of the Armistice, quickly became a bête noire to the German right, who viewed him as a traitor. By 1921, he had retreated to the backbenches of the Reichstag. Organisation Consul, a violently anti-Semitic and ultranationalist terror group formed after the dissolution of the Ehrhardtbrigade (the main force behind last year’s Kapp Putsch), assassinated Erzberger on August 26. The two assassins escaped Germany and would not stand trial until after World War II.

His funeral, on August 31, became a political rally for his Zentrumparty; the keynote speaker was his long-time ally, Chancellor Joseph Wirth. In Berlin, over 100,000 workers, mostly members of the SDP and other left-wing parties, demonstrated in support of the fragile German Republic.

The Cenotaph, pictured between 10:30 and 11AM on November 11, 1920. The casket of the Unknown Warrior, drawn by a gun carriage, is partially obscured behind a tree.

November 11 1920, London–The official Victory Parade, celebrating the Allied victory in the war, was held in July 1919. It featured a cenotaph–an empty tomb–commemorating all the soldiers of the British Empire who had fallen overseas, their bodies buried there. The 1919 cenotaph was a temporary construction, but it was so popular (over a million people visiting the structure in the week after the parade) that there were soon calls for a permanent version.

The permanent Cenotaph, built on the same site in Whitehall as the temporary one, was built between May and November 1920, ahead of the unveiling on the second anniversary of the Armistice. As part of the ceremony, it was also decided to exhume an unidentified British soldier from France and bury him as the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey (not in the Cenotaph itself, which was intentionally empty).

At 11 AM, exactly two years after the Armistice went into effect, King George V pulled a lever, revealing the Cenotaph from under the two large Union flags that had covered it. The crowd stood in silence for two minutes, the “Last Post” was sounded on bugle, and the King laid a wreath before the unveiled cenotaph before the procession continued to Westminster Abbey. There, the pallbearers, which included Marshals Haig and French and Admiral Beatty, bore the casket inside, where it was interred after a brief and solemn ceremony.

Until closed at midnight, crowds filed by both the Cenotaph and the tomb in Westminster Abbey. Within a week, well over a million had paid their respects, and the Cenotaph was partially buried in a pile of wreaths and flowers over ten feet high.

In the Spring of 1919, six months after Armistice Day, the 28th Division returned home to Philadelphia. They were welcomed by a crowd of thousands, who joined them in parade down Chestnut Street.

Happy Veterans Day!

Return of 28th Division from World War. Phila. Pa., Spring of 1919.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Robert Laurence Binyon

from “For the Fallen”

When the Imperials came, they seriously upset the power structure in Morrowind as well as establishing some trade relationships that might be seen as exploitative. Their relationship with most Dunmer (at least ones that did not directly profit from this arrangement) was thus somewhat tense.

Politics

The Empire is largely responsible for the confusing spagetti-like nature of Morrowind’s politics. Traditionally the country was a theocracy ruled by the Tribunal and the Grand Council, with local political matters handled by individual Great Houses. In order to consolidate power in Morrowind, the Imperials imposed a completely different political system over top of the native one, and they exist concurrently. This takes the form of system of Dukes and Governors, presided over by a figurehead King. The Skeleton Man Interviews also mention an ineffectual “Imperial Proconsul” stationed in Narsis. These figures were largely selected from the Empire-friendly Hlaalu faction, which caused bitter tensions between ruling groups, and directly caused the decline of House Indoril, who had been the dominant House for three thousand years prior to Imperial rule. “On Morrowind” describes how the armistice sparked a power grab by Hlaalu, taking over a number of Indoril towns in a series of bloody coups.

We also see tensions between the religious leadership and the imperialized leadership: for example, the power struggle between Hlaalu Helseth and Almalexia in Mournhold. The Imperially sanctioned rulers hold a great deal of power in Morrowind, and the construction of all settlements on Vvardenfell are at the Duke’s discretion. A number of these individuals, such as Governer Ordal Helvi are corrupt leaders. Most Dunmer see the King as an imperial puppet and prefer council rule according to morrowind dialogue. At best, the Dunmer tend to see the Imperial leadership as ineffectual and out of touch with the Province, while at worst they see them as hostile and exploitative invaders attacking their institutions and exploiting their resources. The old guard views Imperial rule as inherently blasphemous and a large number of Indoril leaders actually committed suicide when the armistice was signed.

The Imperial Office of Census and Excise is an administrative arm responsible for conducting headcount, assessing and collecting taxes, handling import licenses, incorporating mercenary guilds, and investigating tax evasion and smuggling. I’m not sure what their relationship to the Duke/King/Emperor is.

In terms of law, again Morrowind is under two coexisting systems, the Imperial and the native. Conflicts between these are governed by the Armistice, which mostly settles in favour of Dunmer tradition in regards to slavery, religion, necromancy and the authority of the great houses. It seems the Empire was willing to make concessions in favour of protecting Dunmer religion and self governance in exchange for very strict control of Morrowind’s resources and economy. They’re kind of hands off, letting Hlaalu use the puppet government for their political advantage while focusing mainly on their trade relationships with morrowind.

Economics

The Imperials forced Vvardenfell to be opened up for trade and settlement so that they could profit from the Ebony, Dwemer artifacts, and other resources in the area. Since prior to this the island was a sacred temple reserve, the move did not really endear them to the religious Dunmer, although a number of factions (especially the Telvanni) used it as an opportunity to expand their holdings. They established the East Empire Trading Company to handle extracting these resources from the region, an organization which proved to be as problematic as its real-world counterpart. The board of directors is appointed directly by the Empire and acts in accordance with Imperial interests. Despite the Empire’s official anti-slavery stance, the company had no problem exploiting local customs and ran an enormous Ebony mine out of Caldera which appears to be one of the largest slave-holders in Vvardenfell. The Empire profited enormously from this hypocrisy.

The Empire had a chokehold on trade and services in Morrowind. The EEC had a legislated monopoly on the trade of all Dwemer artifacts from the region, meaning that the Dunmer had no right to the history and artifacts of their own land. These sorts of restrictions are part of why smuggling is such an enormous industry in Vvardenfell. They also held a monopoly on raw ebony, glass, and flin. It is illegal to mine or export Ebony without an imperial charter. The monopoly had the unintended consequence of fueling an enormous black market headed by the heavily anti-empire Cammona Tong crime syndicate. Even for items which they do not have sole authority over, the EEC enjoys favourable tariffs and regulations that give them the upper hand in exportation. The Armistice also grants the Mages’ Guild a monopoly on magical training and services, a situation you are asked to negotiate in the House Telvanni questline.

There is also something kind of shady going on where the Empire has a high tax on local alcohol and a low tax on Flin imported from Cyrodiil, which the EEC just happens to have an import monopoly on. Essentially they are preventing Dunmer from affording their native liquors in order to sell them cheap flin, which only the EEC is allowed to import. Again, this fuels a smuggling ring for local alcohols which appears to have ties to the Sixth House.

Many Dunmer seem to have been hoping to return to an independent Morrowind. The Nerevarine cult believed that the Nerevarine would deliver Morrowind from Imperial rule, while the Sixth House also had a mandate to drive out the Empire. The Cammona Tong sympathized with them for this reason. Hlaalu found their relationship with the Empire profitable, but even Helseth wanted to shrug off some Imperial control and consolidate native power. In my opinion however, the Empire’s real strategy was not to control Morrowind politically so much as economically, since resource exploitation was their true motive. As soon as the relationship was no longer profitable to the Empire post red-year, the province was largely abandoned to its own devices and the feudal kingship system the imperials introduced disappeared.

ICYMI, our new partnership with Manual Cinema in honor of 100 years since the end of World War I is here! Three World War I Poems brings a selection of poems to life with innovative paper puppetry and animation work, each vignette sharing a different experience of “the war to end all wars” from a soldier’s point of view.

[video: Three interwoven vignettes of interpretations of “The Owl” by Edward Thomas, “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen, and “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae.]

‘Men Marched Asleep’ (2018)

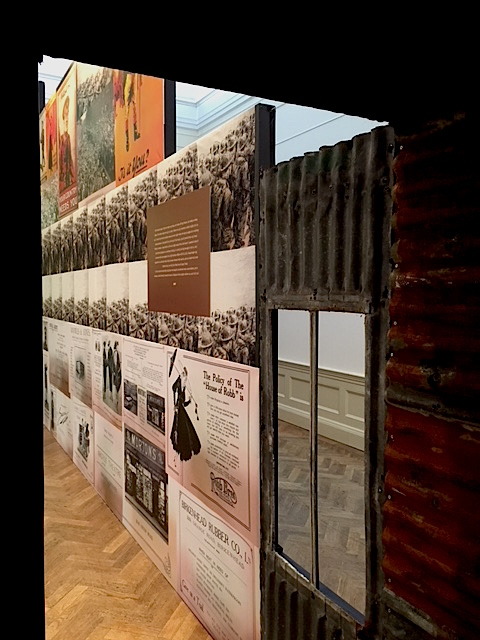

Williamson Museum and Art Gallery, Merseyside, CH43 4UE

Nov - Dec 2018

Heritage Lottery Funded

The title of the installation takes its inspiration from the fifth line of the Wilfred Owen poem: Dulce et Decorum Est

…a poem which provides a deeply evocative description of men exhausted by battle but continuing on. It’s a journey-narrative saturated by time-and-toil, regimental history and personal loss during the Great War. This sense of movement is conveyed in parallel by the installation itself as a series of historical objects, personal photographs and artworks created by the local community transport the visitor through an immersive and evocative environment peppered with lines taken from the poetry of Owen alongside a life-size trench.

Serving & former soldiers contributed to a workshop programme alongside members of The Spider Project, a creative arts and well-being recovery community programme.

Post link

Calling Lost Families by Eunsook Lee

This powerful project was installed in South Korea on the 60th anniversary since the armistice of the Korean War.

Post link

Wednesday Armistice Warmup

Self-reblogging some badass ladies

another reblog of an oldie for Westworld Day!

Post link