#proenneke

“My plastic water bucket dripping a bit so I mixed up a little epoxy, which is the one item more than anything else that holds ‘One Man’s Wilderness’ together.”

- Richard Proenneke, March 11, 1978, in More Readings from One Man’s Wilderness: The Journals of Richard L. Proenneke, 1974-1980 (p. 258)

Landscapes of Literature: Richard Proenneke

Richard “Dick” Proenneke built his cabin on the shore of Upper Twin Lake during the summers of 1967 and 1968. While it wasn’t the first or the largest cabin ever to be constructed in the Alaskan Bush, it stands out for its remarkable craftsmanship and for his documentation of the construction process.

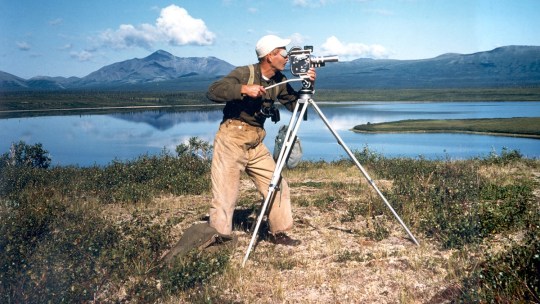

Richard Proenneke at Snipe Lake filming movie clips in 1975. He and his brother Raymond flew there in the J3 Cub. (Photo courtesy of Raymond Proenneke, from NPS / Lake Clark National Park & Preserve website).

Proenneke built an elevated log cache, a combined woodshed/outhouse, and constructed the stone fireplace in the cabin by hand. His building style responded to the unique area and was intended to be both aesthetically appealing and functional for year-round living at Upper Twin Lake.

Proenneke lived in the cabin for 30 years without electricity, running water, a telephone, or other modern conveniences. Despite his remote location and fierce independence, he did not live removed from society. Proenneke maintained friendships, wrote letters, and interacted with pilots, fishermen, neighbors, and park rangers.

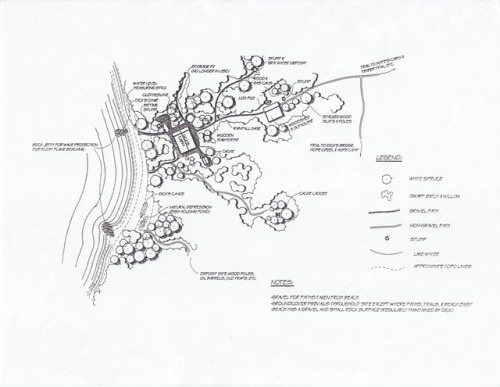

He chronicled his experiences and observations at Twin Lakes through correspondence, annotated calendars and maps, films, and journals. He always tacked a pin in a map before he would set out hiking, the marker showing where he intended to go and the holes across the map’s surface telling of past destinations.

Proenneke used the elevated cache to store various goods, including flour, candy, clothing, filming equipment, and aircraft parts (NPS).

Richard Proenneke was also intimately connected to his natural surroundings. As a result of his observations and advocacy, he became well known during the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) debate of the 1970s, inspiring several books and films and encouraging public support for wild lands in Alaska.

A strong proponent of preservation of the Twin Lakes-Lake Clark country, he gradually came to support the establishment of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. He became a volunteer with the park, helping NPS personnel to monitor weather, collect botanical specimens, assist with aerial wildlife counts, and coordinate float plane pickups between rangers and visitors.

Icicles frame a view of the mountains and lake visible from Richard Proenneke’s cabin (NPS).

Dick Proenneke kept a journal from his first visit to Twin Lakes in 1962. The publication of some of those journals in 1973 as One Man’s Wilderness (edited by Sam Keith) was largely responsible for bringing wider public recognition to Proenneke and Twin Lakes. Eventually, additional journals were published and documentary profiles were created using Proenneke’s own film footage, showing his relationship to the landscape.

Watch it:

In 2000, he and his brother, Raymond, donated all his journals to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

Proenneke’s voice was influential in shaping the preservation of wilderness in Alaska. His words and films reflect his pragmatism and care for this place and profoundly shaped public awareness of the values of Alaska’s wilderness. Richard Proenneke died in 2003, but the values of wilderness preservation and resource protection that he embodied live on through his journal entries and in the features of the cultural landscape.

Learn More

- To find journals, video, landscape details, and inspiration from Dick Proenneke, start here at the Lake Clark National Park & Preserve website: Richard L Proenneke

- Virtual Tour: Explore Lake Clark Wilderness at Upper Twin Lake

- More about ANILCA and Alaska Wilderness (NPS Alaska Nature and Science)

- What are cultural landscapes?

Post link