#cultural landscape

A Landscape of Change: Cape Hatteras Light Station

Twenty years ago, in the summer of 1999, the Cape Hatteras Light Station was moved 2,900 feet from the spot where it had stood since 1870.

As the natural process of shoreline erosion transformed this dynamic coastal environment, the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States now stood dangerously close to the ocean’s edge.

The remarkable undertaking including efforts to protect the structures, maintain the coastal setting of the original site, and preserve the original orientation to the shoreline and spatial arrangement of historic structures in the landscape.

Discover more about the transformation and preservation of this cultural landscape: Landscapes of Change: Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

- Photo album of the 1999 Cape Hatteras Light Station move

- Cape Hatteras Light Station Cultural Landscape Report

- Cape Hatteras Light Station Cultural Landscape Inventory

- Cape Hatteras National Seashore website

- More about cultural landscapes

Driving the lighthouse along the beach to its new location on June 24, 1999 (NPS).

Post link

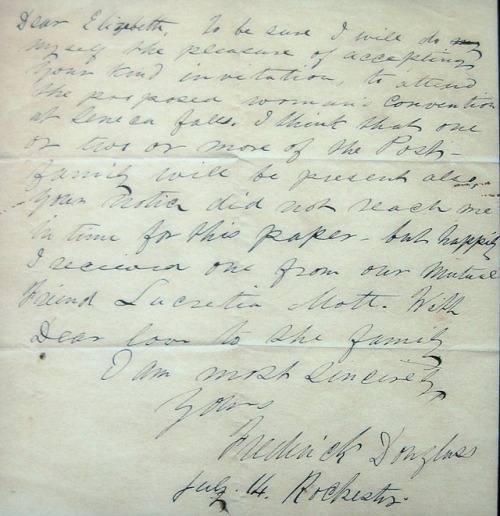

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

- 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution

Convention Days at Women’s Rights National Historical Park

The year 2020 will mark the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment.

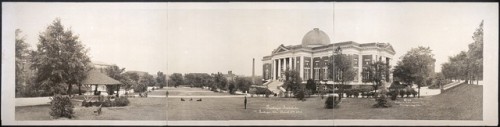

Early women’s rights activists dedicated years, and in some cases most of their lives, advocating for the right to vote. Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, New York commemorates one of the earliest women suffrage movements in United States history. It was here the first Women’s Rights Convention took place in 1848, attracting nearly 300 men and women to debate and exchange ideas regarding the social, civil, and moral rights of women.

The park tells the story of this event through a variety of sites including Wesleyan Chapel, where the convention was held, as well as the homes of renowned women rights activists Jane Hunt, Mary Ann M'Clintock, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton who launched the women’s rights reform movement. They contributed to the creation of the Declaration of Sentiments, which proclaimed that “all men and women are created equal.”

If you find yourself in Seneca Falls this weekend, the park is hosting Convention Days on July 19-21, 2019.

The event is a unique opportunity learn about the early days of the women’s rights movement and the factors that impacted its development. Not-to-miss events include ranger-guided tours, reenactments of the Declaration of Sentiments speech, and the opportunity to meet Coline Jenkins, great-great granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who will present the keynote address!

Learn More

- You can explore some of the other locations marking the women’s rights movement in this country with this Story Map: Women’s Suffrage and the Ratification of the 19th Amendment.

- Find other NPS resources related to Women’s History, including a timeline of the state-by-state race to ratification of the 19th amendment.

Stanton House and surroundings at Women’s Rights National Historical Park in New York (NPS).

Post link

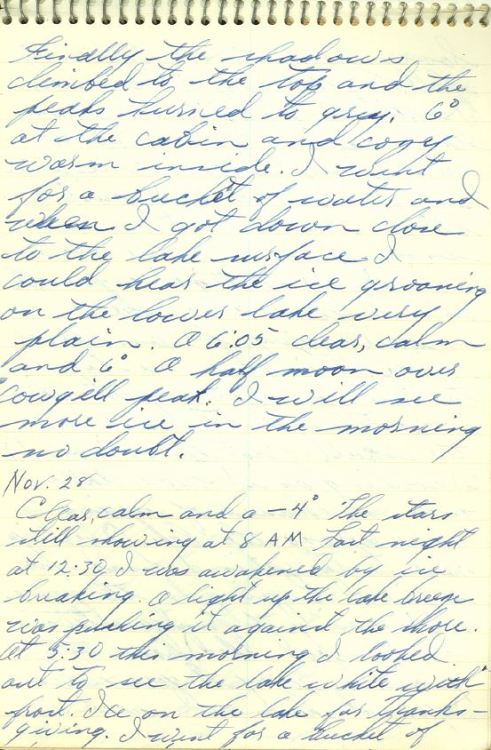

“My plastic water bucket dripping a bit so I mixed up a little epoxy, which is the one item more than anything else that holds ‘One Man’s Wilderness’ together.”

- Richard Proenneke, March 11, 1978, in More Readings from One Man’s Wilderness: The Journals of Richard L. Proenneke, 1974-1980 (p. 258)

Landscapes of Literature: Richard Proenneke

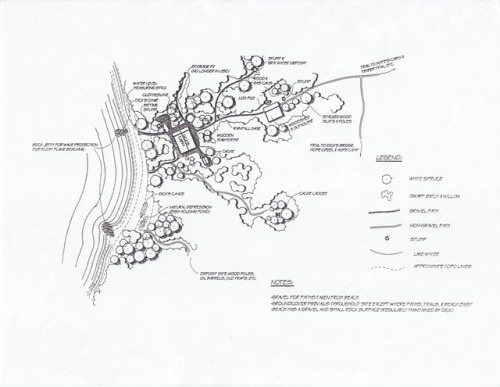

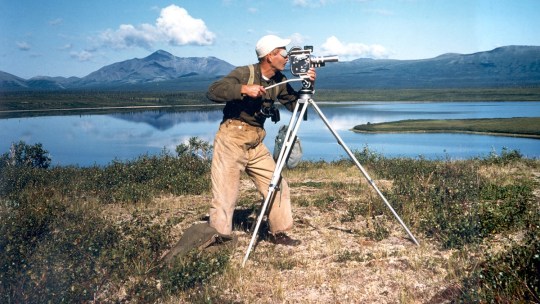

Richard “Dick” Proenneke built his cabin on the shore of Upper Twin Lake during the summers of 1967 and 1968. While it wasn’t the first or the largest cabin ever to be constructed in the Alaskan Bush, it stands out for its remarkable craftsmanship and for his documentation of the construction process.

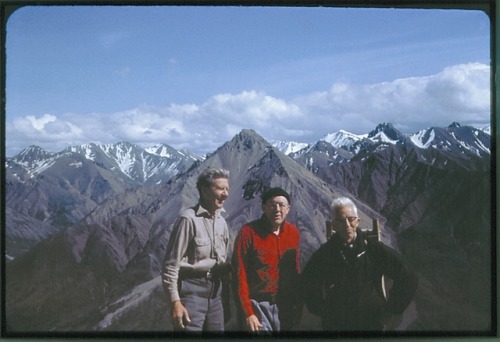

Richard Proenneke at Snipe Lake filming movie clips in 1975. He and his brother Raymond flew there in the J3 Cub. (Photo courtesy of Raymond Proenneke, from NPS / Lake Clark National Park & Preserve website).

Proenneke built an elevated log cache, a combined woodshed/outhouse, and constructed the stone fireplace in the cabin by hand. His building style responded to the unique area and was intended to be both aesthetically appealing and functional for year-round living at Upper Twin Lake.

Proenneke lived in the cabin for 30 years without electricity, running water, a telephone, or other modern conveniences. Despite his remote location and fierce independence, he did not live removed from society. Proenneke maintained friendships, wrote letters, and interacted with pilots, fishermen, neighbors, and park rangers.

He chronicled his experiences and observations at Twin Lakes through correspondence, annotated calendars and maps, films, and journals. He always tacked a pin in a map before he would set out hiking, the marker showing where he intended to go and the holes across the map’s surface telling of past destinations.

Proenneke used the elevated cache to store various goods, including flour, candy, clothing, filming equipment, and aircraft parts (NPS).

Richard Proenneke was also intimately connected to his natural surroundings. As a result of his observations and advocacy, he became well known during the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) debate of the 1970s, inspiring several books and films and encouraging public support for wild lands in Alaska.

A strong proponent of preservation of the Twin Lakes-Lake Clark country, he gradually came to support the establishment of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. He became a volunteer with the park, helping NPS personnel to monitor weather, collect botanical specimens, assist with aerial wildlife counts, and coordinate float plane pickups between rangers and visitors.

Icicles frame a view of the mountains and lake visible from Richard Proenneke’s cabin (NPS).

Dick Proenneke kept a journal from his first visit to Twin Lakes in 1962. The publication of some of those journals in 1973 as One Man’s Wilderness (edited by Sam Keith) was largely responsible for bringing wider public recognition to Proenneke and Twin Lakes. Eventually, additional journals were published and documentary profiles were created using Proenneke’s own film footage, showing his relationship to the landscape.

Watch it:

In 2000, he and his brother, Raymond, donated all his journals to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

Proenneke’s voice was influential in shaping the preservation of wilderness in Alaska. His words and films reflect his pragmatism and care for this place and profoundly shaped public awareness of the values of Alaska’s wilderness. Richard Proenneke died in 2003, but the values of wilderness preservation and resource protection that he embodied live on through his journal entries and in the features of the cultural landscape.

Learn More

- To find journals, video, landscape details, and inspiration from Dick Proenneke, start here at the Lake Clark National Park & Preserve website: Richard L Proenneke

- Virtual Tour: Explore Lake Clark Wilderness at Upper Twin Lake

- More about ANILCA and Alaska Wilderness (NPS Alaska Nature and Science)

- What are cultural landscapes?

Post link

Landscapes of Literature: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Tucked away in a pleasant, residential neighborhood, not too far away from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

Each spring, lilacs bloom on the hedges surrounding Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site (NPS).

This site preserves an elegant house which served as headquarters for General George Washington during the Siege of Boston and as the home of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807 -1882), one of the most famous American poets of the 1800s. For 45 years, Longfellow lived here with his family in the Georgian style mansion, looking out upon picturesque estate grounds that included a formal garden, woodland walk, lilacs, elm trees at the front of the house, a view to the Charles River, and outbuildings like the carriage house.

River! that in silence windest

Through the meadows, bright and free,

Till at length thy rest thou findest

In the bosom of the sea!

Four long years of mingled feeling,

Half in rest, and half in strife,

I have seen thy waters stealing

Onward, like the stream of life.

Thou hast taught me, Silent River!

Many a lesson, deep and long;

Thou hast been a generous giver;

I can give thee but a song.

Oft in sadness and in illness,

I have watched thy current glide,

Till the beauty of its stillness

Overflowed me, like a tide.

– excerpt from “To the River Charles” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in Ballads and Other Poems(1842)

While in residence, he published eleven poetry collections, two novels, several plays, three epic poems, including Paul Revere’s Ride,The Village Blacksmith,Evangeline,The Song of Hiawatha, and notable translations such as Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

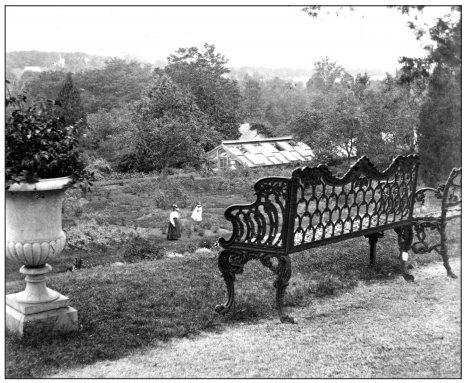

The Formal Garden

Longfellow and his daughter, Alice, shared an interest in landscape architecture, represented by the formal grounds, including a garden on the northeast end of the property which they carefully designed over time. Longfellow imported a variety of exotic evergreen trees from as far as the Himalayas, Northern Europe, and Oregon with help from renowned botanist Asa Gray.

In 1847, he sought the assistance of landscape architect Richard Dolben to create a new designed garden. Following Longfellow’s death, the formal garden was renovated by his daughter to its current Colonial Revival layout in 1904-05 and 1925.

In 2005-06, the garden was restored based on historical documentation in the site’s archives, largely based on the earlier 1925 rehabilitation by noted landscape architect Ellen Shipman. A large European linden stands in the east lawn toward the rear of the house, where this garden remains on the footprint of the original 1847 design.

Formal garden, looking northwest toward arbor. Wheelchair is visible in garden with occupant (possibly Alice Longfellow, 1888-1928), ca. 1904-C1928. The arbor was added by Martha Brookes Hutcheson (1904) and removed (1932/34). (National Park Service / Longfellow House Washington’s Headquarters, LONG 7503).

Expressions

From the time that he first starting renting two rooms on the house’s second floor, the letters and journals of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow expressed that the history and character of the grounds were a source of both pleasure and inspiration for him.

In one journal entry, he writes, “How glorious these Spring mornings are! I sit by an open window and inhale the pure morning air, and feel how delightful it is to live! Peach, pear and cherry trees are all in blossom together in the garden.” [1]

Later, in an 1843 letter to his father, Longfellow described the past and future of the landscape:

We have purchased a mansion here, built before the Revolution, and occupied by Washington as his Headquarters when the American Army was at Cambridge. It is a fine old house and I have a strong attachment from having lived in it since I first came to Cambridge. With it are five acres of land. The Charles River winds through the meadows in front and in the rear I yesterday planted an avenue of Linden trees, which already begin to be ten or twelve feet high. I have also planted some acorns and the oaks grow for a thousand years, you may imagine a whole line of little Longfellows, like the shadowy monarchs of Macbeth, walking under their branches for countless generations, “to the crack of doom,” all blessing the men who planted the oaks.[2]

South facade of Longfellow House taken from outside fence on Brattle Street, 1910 (National Park Service, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters, Archives Number: 3008-1-1-17).

Longfellow Summer Festival

If you find yourself in Cambridge on a summer day, celebrate the history of the cultural landscape and contemporary poets and creators at the annual Longfellow Summer Festival. The festival, a tradition nearly as old as the park itself, brings music and poetry alive at the Longfellow House on Sunday afternoons through August.

- For the schedule of upcoming events: 2019 Summer Festival

Garden in bloom at Longfellow House - Washington’s Headquarters NHS (NPS).

Learn More

- Longfellow House - Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site Digital Archive

- Longfellow House - Washington’s Headquarters Landscape Cultural Landscape Inventory

- Cultural Landscape Report: Longfellow National Historic Site, Volume 1, Site History and Existing Conditions

- Cultural Landscape Report: Longfellow National Historic Site, Volume 2, Analysis of Significance and Integrity

- Plan Your Trip: Longfellow House - Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site park website

- What are cultural landscapes?

*Thanks to the Longfellow House - Washington’s Headquarters NHS and others for help preparing this story!*

[1]Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Journals, Cambridge, May 20, 1838, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, as cited by Evans in Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, Volume 1: Site History and Existing Conditions, 1993, 33.

[2] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Ferdinand Freiligrath, November 24, 1843, as cited by Luzader in Historic Structures Report, Longfellow House: Historical Data, 1974, 23.

Post link

Reading the Landscape

This month, we are celebrating a few of the authors, journalists, and poets associated with places that we now know as part of the National Park System. The NPS helps to preserve the legacy and perspective of writers through park cultural landscapes, allowing us to envision the places in which their words were imagined.

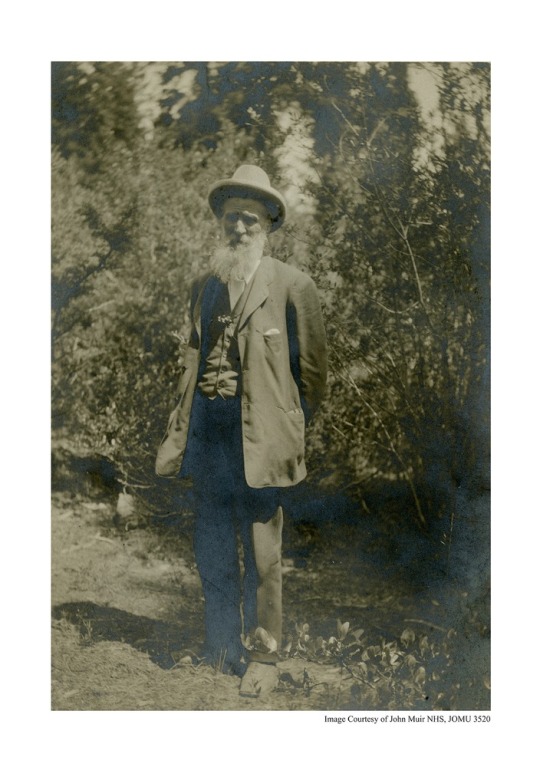

The NPS preserves places that are associated with the literary contributions of specific individuals, like John Muir National Historic Site andEdgar Allan Poe National Historic Site, but literary discoveries are not limited to those parks.

John Muir, ca. 1910 (NPS / JOMU 3520)

Some of these written expressions are our first introduction to a place, leading us to it or reflecting the historic character of a park cultural landscape. Others reveal the author’s unique relationship to those surroundings. Sometimes, the landscape acts as the entryway to discover the writing, giving dimension to the words.

Whether you are planning summer reading or a summer road trip, we hope you find new places to explore in our landscapes of literature mini-series.

Follow along, catch up, or add you own favorites with #literarylandscapes.

Featured:

- Adolph Murie: Wildlife Biologist, Conservationist (Denali National Park & Preserve)

- Writings of John Muir (Sierra Club)

Post link

50 Years Since Stonewall

Located in New York City’s Greenwich Village, Stonewall National Monument is a National Park Service site dedicated to a key turning point in the modern lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer civil rights movement.

On June 28, 1969, patrons, employees, and police clashed during a raid on the Stonewall Inn. The confrontation spread into the neighboring streets and adjacent Christopher Park. The days-long uprising marked a significant moment in the struggle for LGBTQ rights, providing momentum for the movement well beyond the streets of New York City. Within two years, gay liberation groups were established in almost every major city across the U.S.

The Stonewall Inn in 2016 (NPS / Schenck)

The National Park Service is committed to telling the history of all Americans in all of its diversity and complexity.

- Discover more about LGBTQ heritage with NPS resources

- Stonewall National Monument: Rising for Equality - Step into the landscape (revisiting a 2017 article)

- What are cultural landscapes?

Post link

Parterre Planting

In 2010, the Falling Gardens at Hampton National Historic Site were rehabilitated to reflect their historic configuration. The six parterres that comprise the Falling Gardens were re-defined on the turf-carpeted terraces and replanted to represent circa-1867 planting schemes.

The garden rehabilitation helped evoke the grandeur of the historic landscape, which had fallen into disrepair by the mid-1900s with missing and overgrown vegetation.

The Falling Gardens and Greenhouse #2 from the Great Terrace, looking southwest, 1872 (NPS/HAMP 3493, in Cultural Landscape Report).

The work didn’t end there, however.

Annuals are planted in the parterres each spring. This year, park staff, a summer work crew of 6 people, and volunteers planted 3,398 plants over a 2-week time period.

Want to see more of the 2019 parterre planting at Hampton National Historic Site?

(Recorded by and shared with permission of Tim Ervin, via Flickr.)

How do Cultural Landscape Reports inform landscape preservation?

Discover history, plant lists, before and after photos of the Falling Gardens, and more about Hampton National Historic Site cultural landscape :

- Cultural Landscape Report, Volume I (Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation)

- Cultural Landscape Report, Volume II (Treatment and Record of Treatment)

The Falling Gardens and Greenhouse #2, c. 1935 (NPS/HAMP 19240, in Cultural Landscape Report).

Post link

Cultural Landscape Preservation

It’s already the end of May, which means that Preservation Month is coming to a close. Here are just a few ways to continue exploring cultural landscape preservation in the National Park Service:

You can also find access to the Integrated Resource Management Applications (IRMA) Portal there, an NPS-wide repository for documents, publications, and data sets related to natural and cultural resources of the National Park Service. The cultural landscape documents in this growing collection contain history, analysis, and treatment recommendations to support the management of cultural landscapes.

These videos highlight preservation projects in various park cultural landscapes, revealing how management documents (like Cultural Landscape Reports) guide preservation treatment that can impact the experience of historic places.

Keep celebrating preservation all year!

Post link

Beautification: A Legacy of Lady Bird Johnson

“The environment after all is where we all meet; where we all have a mutual interest; it is the one thing all of us share. It is not only a mirror of ourselves, but a focusing lens on what we can become.”

- Lady Bird Johnson, “Speech at Yale University,” (New Haven, Connecticut, October 9, 1967).

As a champion of conservation efforts and environmental causes, Lady Bird Johnson initiated the Beautification Project to improve the quality of life for residents of Washington, D.C. through the renewal and improvement of public spaces. The environmental and aesthetic improvements of Beautification included tree-lined avenues, floral displays, design guidelines, improvements to pedestrian circulation, renovation of historic buildings, and litter clean-up.

Beautification Luncheon. Foreground L-R: Sec. Stewart Udall, Lady Bird Johnson, Laurance Rockefeller looking at an architectural model of the Washington DC Mall area during a Beautification Luncheon in the White House State Dining Room. The 1967 luncheon in part discussed proposed changes to the Mall (Robert Knudsen, LBJ Library, White House Photo Office collection (C5209-33).

Beautification was far more complex than a garden club project.

According to Johnson, “Though the word beautification makes the concept sound merely cosmetic, it involves much more: clean water, clean air, clean roadsides, safe waste disposal and preservation of valued old landmarks as well as great parks and wilderness areas. To me…beautification means our total concern for the physical and human quality we pass on to our children and the future.”

Lady Bird Johnson and two young people standing among blooming white azaleas during a Beautification Tour of Washington, D.C. (Robert Knudsen, LBJ Library, C1754-25).

Lady Bird Johnson selected her adopted hometown of Washington, D.C. as the pilot city to show the nation how Beautification could enhance the overall quality of life. The city afforded Johnson the perfect opportunity to showcase the potential of the program. The prominence of Washington, D.C. garnered national visibility to highlight the progress of the effort.

“The Story of Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson’s Beautification Program” is from the LBJ Library moving picture collection created by the White House Naval Photographic Unit, aka the Navy Films. The films consist of monthly reports on the activities of President and Lady Bird Johnson from 1963-1969. This edited content is from the LBJ Library audiovisual archives.

Lady Bird Johnson formed a coalition of both public and private entities, involving Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, local officials, planners, landscape architects, citizens, and school groups.

Spring brings color to the trees on the East Potomac Golf Course at Hains Point in Washington, D.C. (NPS Photo).

Lady Bird’s legacy is still evident in Washington, D.C. today.

Daffodil drifts soften the hillsides of the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway, as well as the George Washington Memorial Parkway and Lady Bird Johnson Park. Cherry trees line the road of Hains Point, sprays of blossoms frame views in the monumental core, and the Floral Library near the Washington Monument bursts with color in the springtime. Street trees shade avenues throughout the city, and efforts to clean the city’s waterways have continued into the present.

Find more in the full article at nps.gov: Beautification: A Legacy of Lady Bird Johnson

Post link

Landscape Design at Cabrillo National Monument

San Diego, California

Cabrillo National Monument was established in 1913 to commemorate explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, who led a European expedition to the west coast of what is now the United States. A statue of Cabrillo gazes out over the San Diego Bay, where his sails arrived ashore on September 28, 1542.

The historic importance of Cabrillo National Monument is associated with multiple resources and periods of time.

Before it became part of the National Park System, it was part of Fort Rosecrans, the headquarters of the WWII harbor defenses of San Diego. Several lighthouses have shone from this shoreline location, aiding navigation and attracting visitors.

Point Loma Lighthouse at sunset (NPS Photo).

More recently, the Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center Historic District landscape is associated with the modern design principles of the NPS Mission 66 program.

Mission 66

Mission 66 was a period of profoundly new design ideas in national parks, expressed through a system-wide program of development. In response to the increasing crowds and automobile traffic of the 1950s, and in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the NPS in 1966, the agency embarked on a plan to overhaul park facilities with an emphasis on improving roads and parking, visitor facilities, and administration, housing areas, and concessionaire areas.

The Cabrillo National Monument was one of the parks that would undergo extensive changes during Mission 66, a critical factor in the development of the site into a modern and fully accessible park. Between 1963 and 67, the Mission 66 master plan added a new entrance road, parking areas, and a Visitor Center with an interior courtyard and series of interconnected indoor and outdoor landscape spaces. It is an example of how Mission 66-era development used concepts associated with modernism in landscape architecture, expressed in a southern California coastal context.

Walkway to the Cabrillo statue at the Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center Historic District landscape (NPS Photo).

More about the Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center Historic District landscape

- Learn more in the Cultural Landscape Inventory report

- Explore the cultural and natural resources at Cabrillo National Monument

- Cultural Landscape Profile: Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center Historic District

Read more about Mission 66

- How Mission 66 Shaped the Visitor Experience at National Parks (National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2/8/17)

- Mission 66 Visitor Centers: The History of a Building Type(Sarah Allaback, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2000) - online book

- Mission 66: Modernism and the National Park Dilemma (Ethan Carr, University of Massachusetts Press in association with Library of American Landscape History, 2007)

Post link

Appomattox Court House Village, April 9

On April 9, 1865, the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia signaled the end of the Civil War. The landscape at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park marks the beginning of the country’s transition to peace and reunification following four years of war. The rural landscape is also significant in areas of architecture and conservation.

In commemoration of the 154th Anniversary of Lee’s surrender to Grant, learn more about the park’s cultural landscape through a new video and the recently published Cultural Landscape Report:

- Discover the Appomattox Court House Village landscape through the latest video from the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation

- TheCultural Landscape Report Treatment Implementation Plan guides long-term management and preservation decisions for this historically significant landscape.

- Visit the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park website to learn more and plan your visit

- More information about the Appomattox Court House Landscape

Thereconstructed McLean House at Appomattox Court House, the site of the surrender on April 9, 1865 (NPS Photo).

The Agricultural Landscape at a Presidential Home

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York

We can almost smell summertime in the latest video from the NPS Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation.

The short video celebrates the agricultural landscape of Lindenwold, President Martin Van Buren’s home and farm, and encourages viewers to learn more about the landscape’s past, present, and future through the lens of the recently published report “Agricultural Management Guidelines for the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site.”

Cover of the management document for the agricultural landscape at Martin Van Buren National Historic Site (NPS Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation).

At the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, the National Park Service collaborates with Roxbury Farm CSA, the Open Space Institute, and the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation to preserve President Martin Van Buren’s historic farmland by supporting sustainable agriculture now and for generations to come.

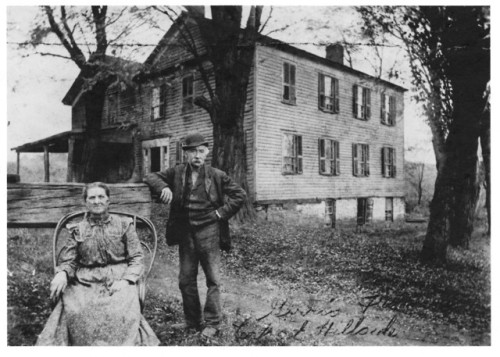

David Williston

David Williston’s legacy can be seen through his work as landscape architect, educator, and horticulturalist.

Recognized as the first professionally-trained African American landscape architect, Williston oversaw the development of the Tuskegee Institute campus, where he also taught as professor of horticulture.

Discover more:Learning from Leaders: David Williston

Post link

Learning in Action

The Designing the Parks program is not your typical internship.

Each year since 2013, the program has introduced a cohort of college students and recent graduates to National Park Service design and planning professions through projects related to cultural landscape stewardship.

In the internships, hosted by the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation and made possible by partner organizations, each participant focuses on an in-depth project that directly engages with a national park unit.

Designing the Parks

Our most recent article highlights the Designing the Parks program, including recent projects and partner organizations: Designing the Parks: Learning in Action

Also, don’t miss the Designing the Parks blog written by the team of interns. Seriously, it’s good.

Discover More:

Video Production Intern, Vanessa Hartsuiker, films on the grounds at Chatham Manor at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park for a cultural landscape report video (NPS Photo).

Post link

The Cultural Landscape at Harriet Tubman National Historical Park

Our nation has a rich legacy of cultural landscapes – from carriage roads to battlefields, designed gardens to vernacular homesteads, and industrial complexes to river valley settlements. The NPS Park Cultural Landscapes Program promotes the stewardship of significant landscapes through research, planning, maintenance, training, and education.

This video introduces the cultural landscape at Harriet Tubman National Historical Park and invites viewers to learn more. NPS staff from the park, descendants of Harriet Tubman, and other people associated with the area describe the features and significance of this unique landscape and actions that have been taken to preserve it.

This video, announced on March 10 in honor of Harriet Tubman Day, is the latest in a series of videos designed to facilitate the transfer of knowledge gained through cultural landscape research and communicate unique aspects of a particular landscape’s history and significance.

- Watch other videos in the series and find audio-described versions: Cultural Landscape Video Series from the NPS Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation

Summer Internship Opportunity

Join the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation this summer as a Digital Media Resource Assistant, supported in partnership with the nonprofit American Conservation Experience.

As the Digital Media Resource Assistant, you will create ArcGIS StoryMaps and other digital media products for a national audience that convey a strong sense of place, sharing stories that capture the diverse perspectives shaping our cultural landscape heritage.

- Don’t miss the Designing the Parks blog to see what other interns with the Olmsted Center have been doing.

- Learn more about the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation.

[Image description: A group of Olmsted Center Associates, interns, gather on a rocky mountaintop in Acadia National Park, overlooking an expanse of trees and water below.]

Post link

Internship Opportunity

Join the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation this summer as a Digital Media Resource Assistant supported through the Latino Heritage Internship Program!

The Digital Media Resource Assistant will create ArcGIS StoryMaps for a national audience that convey a strong sense of place and share stories that are inclusive and capture the diverse perspectives that shape our cultural landscape heritage.

If you have interest and experience in cultural resource management and digital media/GIS, check out the full posting and apply through Environment for the Americas: Digital Media Resource Assistant

More Information

Photo: Reflections in the water in front of Stone Cottage at Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site, which is one of the places this intern will be profiling through the ArcGIS Storymaps.

Post link

Preservation Profile: Dennis Lewarch

Since the late 1960s, the Suquamish Tribe of Washington State has organized to demand their legal and civil rights in a path toward self-determination. Along the way, non-Indian partners like Dennis Lewarch have played important roles as allies.

The Park Cultural Landscapes Program recently had a chance to meet (safely) for conversation with Dennis. He shared reflections on serving the interests of the Suquamish as their first Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO), focusing on completion of a Traditional Cultural Place (TCP) nomination for the National Register.

- Read the Preservation Profile

- More ways to recognize Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian history and heritage, during Native American Heritage Month and year-round: Native American Heritage Month with NPS and partners

Post link

Stewardship at Grand Portage National Monument

The Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and the National Park Service work together at Grand Portage National Monument to support, interpret, and protect the lifeways of the Ojibwe people, including the preservation of historic landscape features of the Grand Portage trail.

The Grand Portage was a vital part of both American Indian and fur trade transportation routes because of the area’s geology, topography, natural resources, and strategic location between the upper Great Lakes and the interior of western Canada. Grand Portage National Monument is in the homeland of the Grand Portage Ojibwe. The Band has long been involved in stewardship of the Monument, where tribe members play a critical role in management, landscape maintenance, and historic preservation.

- Discover more about this agreement, ethnobotanical restoration, the role of the Civilian Conservation Corps – Indian Division during the 1930s, and the youth contributions of the Grand Portage Conservation Crew: Stewardship at Grand Portage National Monument

- Learn more about Grand Portage National Monument

Historic bridge at Grand Portage National Monument before work, date unknown (NPS).

Post link

Internship Opportunity!

Join the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation team this winter (remotely) as a Geographical Information Systems/App Development Intern to help build a web-based mobile app for tree assessment to improve management in the National Park Service.

This individual will build and beta-test a web-based mobile app for tree inventory and condition assessment which will allow for integration of data collection with the arboricultural field manual. They will support and participate in the collection of field data using GIS and develop GIS data structures to capture information through the ESRI Collector. The 1200-hour position is supported through a partnership with the National Council of Preservation Education.

If you have interest and experience in cultural resource management and GIS, check out the full posting and apply through the Handshake job portal (position #4160631) or at PreserveNet.

Details

- Direct link to the position announcement: Geographical Information Systems/App Development Intern

- Find more about the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation: OCLP Internships

- What does an internship with the Olmsted Center look like? Don’t miss the Designing the Parks blog for notes from the field.

- *Closes November 11, 2020*

Post link

Army Corps of Engineers Road System Added to the National Register

Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

The Army Corps of Engineers Road System at Crater Lake National Park is among Oregon’s latest entries in the National Register of Historic Places.

The National Park Service accepted the nomination on August 12. NPS staff historian Stephen Mark took the lead in writing the nomination, which centered on a previously little-known effort by the Army Corps in highway engineering and construction that happened from 1910 to 1919 in the park.

The Army Corps of Engineers Road System, a precursor to the historic Rim Drive, is significant for its association with the earliest period of highway engineering in Oregon.

As Stephen Mark describes, “Unlike today’s roads, this system came into being with hand tools, horse power, and a couple of wood-burning steam shovels.”

The road system was the first federally funded and supervised highway project in Oregon and is the only road project in Oregon attributed to the Army Corps of Engineers.

The road system is the fourth historic district listed at Crater Lake National Park, with others at Rim Village, at Park Headquarters and along Rim Drive.

- Discover more about the nomination and the history of the road system: News Release: “National Register Listing for Army Corps of Engineers Road System”

- Visit the park website to plan your visit: Crater Lake National Park

- Find more from the National Register of Historic Places

A car on a road in front of impressive snow banks, almost completely obscuring a house, shows the winter conditions at Crater Lake, 1949.

(NPS/Harpers Ferry Center Archives)

Post link

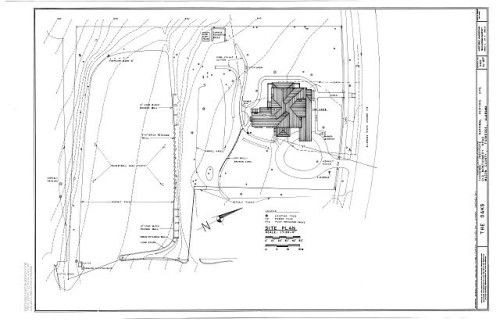

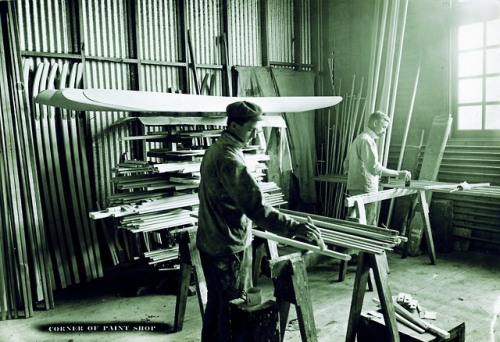

The Wright Company

Brothers Wilbur Wright (1867-1912) and Orville Wright (1871-1948) built their first experimental airplanes in the back of their bicycle shop at 1127 West Third Street in Dayton, Ohio. They formed the Wright Company in November 1909. The Wright Company started manufacturing airplanes in Dayton, and it coordinated the Wright Exhibition Team and Flying School at Huffman Field to help market their invention.

The Wright Exhibition Team operated only briefly from 1910-1911, while the Flying School lasted through 1916. Civilians and military aviators trained at the Flying School at Huffman Field, which was characterized by uneven and sometimes marshy terrain.

“Here we must depend on a long track, and light winds or even dead calms. It is skirted on the west and north by trees. This not only shuts off the wind somewhat but also probably gives a slight downtrend. However, this matter we do not consider anything serious. The greater troubles are the facts that in addition to cattle there have been a dozen or more horses in pasture and as it is surrounded by barbwire fencing we have been at much trouble to get them safely away before making trials. Also the ground is an old swamp and is filled with grassy hummocks some six inches high so that it resembles a prairie-dog town.”

–Wilbur Wright to Octave Chanute, June 21, 1904, cited in the Huffman Prairie Flying Field Cultural Landscape Report (pg. 13)

The Wright Company started by producing airplane engines and drive trains in their bicycle shop before eventually moving into their new factory.

On September 9, 2019 the Wright Company Factory was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Dayton’s identity as a city of innovation and industry allowed the Wright Company better access to skilled workers and machinery. The Wright Company produced approximately 120 airplanes in 13 different models and introduced industrial aviation.

Explore this history through some of the cultural landscapes of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park:

More:

- Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park: Visit the park website to learn more and plan your own visit

- “Wright airplane factory placed on national historic registry,” Dayton Daily News, September 16, 2019

- The Wright Company Factory Site, National Aviation Heritage Area

- Wright Brothers Photograph Collection: Wright State University Special Collections

- Wright Brothers Negatives Collection: Library of Congress

- What are cultural landscapes?

Post link

The Legacy and Landscape of Harriet Tubman

To help honor Harriet Tubman’s first attempt at self-emancipation on September 17, 1849, the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation has created a short video highlighting Harriet Tubman, the remarkable landscape of Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland, and some of the cultural landscape research they’ve conducted there to date.

“The Cultural Landscape at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park” is the latest addition to the Olmsted Center’s cultural landscape video series. Each video highlights the unique aspects of a particular landscape’s history and significance, and together they help to communicate the process and outcomes of cultural landscape research.

- Find the full series at the link below, or at the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation website

Stewart’s Canal at dusk, at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park (NPS).

Discover More

- Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park website

- Underground Railroad: More on this subject from the National Park Service

- Journeying toward Freedom and New Beginnings: A cultural landscape perspective of Harriet Tubman and the Jacob Jackson home site on the Eastern Store of Maryland

- Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation video series (YouTube)

- More about NPS cultural landscapes

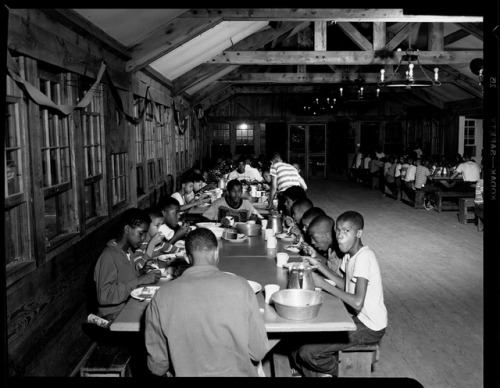

Field School at Prince William Forest Park

September has arrived. It’s the time of year when many people return to classrooms and get ready for the school year ahead. It’s also a great time to reflect on ongoing educational partnerships and the year-round learning that takes place out of the classroom.

Beginning in summer of 2018, students from the University of Mary Washington participated in a field school to document two cultural landscapes at Prince William Forest Park, Cabin Camp 2 and Cabin Camp 4. The Cabin Camps at Prince William Forest Park were developed in the 1930s as part of the Recreation Demonstration Area program.

The typical four-person sleeping cabin in Cabin Camp 2 at Prince William Forest Park (NPS).

Over several weeks, the students documented existing conditions of landscape features. In addition to the hands-on experience, their documentation will be used to complete Cultural Landscape Inventory (CLI) reports, which are an important tool for the continued management of park cultural landscapes.

The outcomes and lessons learned by the National Park Service, UMW faculty, and students helped shape the 2019 field season and will serve as a model for future iterations of the field school.

- Learn more about this educational partnership to document these cultural landscapes and the history of the cabin camps in our latest article: Field School at Prince William Forest Park

- More about Prince William Forest Park

- Historic Preservation at University of Mary Washington

- What are cultural landscapes?

(Thanks to colleagues in the National Capital area for assistance with this article!)

Post link

The Valley Railway

Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Ohio

By the 1850s, railroads began to replace canals and riverboats as a more efficient transportation option. The Cuyahoga Valley Railway served as the primary rail transportation for the Valley from 1871 to 1915, and the railway evolved into a part of everyday life for residents throughout Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley.

Along the Valley Railway, new structures were built to accommodate the goods and people moving along the route. Bridges allowed the railroad to cross the ever changing topography. Mills which soon grew into company towns were constructed along the expanding route, as farmers embraced the railroad to ship their products to markets in Cleveland or Akron.

The ultimate end of the Valley Railway’s existence came in 1915 when the B&O assumed complete ownership of what had by that time been renamed as the Cleveland, Terminal and Valley Railroad. Five years later, in 1920, rail companies nationwide were forced to examine their role with the realization that there were cheaper and more efficient modes of transportation capable of carrying loads of coal, heavy ores, passengers and a wide variety of materials via the use of semi-trucks and more powerful locomotives. Because the region – and the nation – was now experiencing the positive commercial effects of alternative shipping methods, heavy reliance on rail service in the Cuyahoga Valley declined.

When interest in the line was renewed as a scenic excursion route in the early 1970s, the Cuyahoga Valley Preservation and Scenic Railway Association was formed. Originally known as the Cuyahoga Valley Line, the scenic railroad now operates as Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad. Although it’s just one part of the transportation history of this area, the vital role of the Valley Railway can still be seen across the landscape at Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Read the full article at nps.gov: Find more about the transportation history of this area, the development and decline of the Valley Railway, and the features of the cultural landscape: Cuyahoga Valley Railway Cultural Landscape

Thanks to Historian Larry Johnson for contributing this article!

Post link

Point Reyes Lifeboat Station Cultural Landscape

Point Reyes has the only surviving lifeboat station on the Pacific Coast with an intact marine railway. The lifeboat station has stood at the eastern tip of the Point Reyes peninsula (part of Point Reyes National Seashore) since 1927. In June of 2019, a crew launched a restored lifesaving boat along the marine railway and into the water of Drakes Bay.

From 1927 to 1968, the Pacific Area U.S. Coast Guard officers and crew members used motorized lifeboats to aid ships in distress. During World War I and World War II, the primary operations of the life-saving station shifted to coastal defense and harbor patrol.

- Take a look at our latest article for more about this cultural landscape, including several 360 degree photos that document the landscape and the interior of the boat house: Remembering Maritime Life: The Point Reyes Lifeboat Station Historic District

- For more information or to plan your own visit, find the park website: Point Reyes National Seashore

- More about NPS cultural landscapes

Post link

Links to the Past: Public Golf Courses of Washington, D.C.

The three National Park Service golf courses in Washington, D.C. have a fascinating and complex history. Initially built between 1918 and 1939, the courses have hosted numerous tournaments, presidents of the United States, renowned American golfers, and countless local citizens.

The golf courses also played a role in the civil rights movement. Activists successfully protested for equal access to the courses and helped inspire the integration of the city’s recreational facilities in 1941.

TheNPS has completed studies on the history and design of the three golf courses (East Potomac Golf Course, Langston Golf Course, and Rock Creek Golf Course), including treatment guidelines for the long-term stewardship of the courses.

Now, a long-term lease opportunity is available for the golf courses, and the NPS is in search of an operator who’s committed to providing affordable and easy-to-access golfing, to improving facilities and courses, and to preserving the unique histories and landscapes of each of these courses.

For information about developing and submitting a proposal:

- News release: “Hole-in-one business opportunity with the National Park Service”

- Request for Proposals (RFP)

- Proposals must be received by the NPS by 4pm EST on November 27, 2019.

Langston Golf Course, first opened in 1939, is one of three 18-hole golf courses on National Park Service land in Washington, D.C. (NPS).

Post link

Caroline Lockhart: Author, Newspaper Publisher, Investigative Reporter, Rancher

Caroline Lockhart began her career as a journalist at the age of 18. In 1889, she became a reporter on the Boston Post. She quickly became known for her adventuresome, independent spirit, pursuing tough assignments as she developed one of her literary principles: “…I have endeavored to know what I am writing about before I write.”

Later, traveling on assignment for a story about the Blackfeet Indians, Lockhart found Cody, Wyoming and the surroundings to be to her liking. It was also a useful backdrop and inspiration for her books, often focused on western themes and characters.

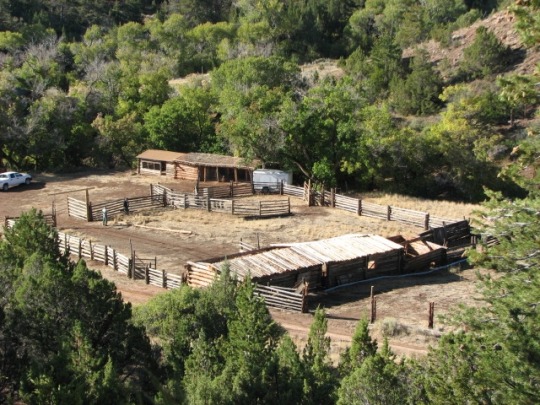

The Lockhart Ranch

In 1926, she purchased a ranch in Montana, located in what is today Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. She inherited a two-room cabin, a few run-down sheds, and 20 acres of cultivated ground from the previous owners of the ranch. In addition to it being her residence and a retreat in which to pursue her writing, she added to the acreage and developed a sizable commercial ranching operation. She landscaped the area around the cabin with irises and hollyhocks, planted cottonwood trees for shade, and built stone pathways. She also constructed fences, corrals, irrigation systems, and additional structures.

Main ranch house at Lockhart Ranch (NPS).

Life on the ranch, which she expanded in size to over 6,034 acres, was mostly self-sufficient, as evidenced by features of the landscape. A storage building was used to keep potatoes, apples, and meats. Milk, butter, and eggs from ranch cows and chickens went from the milk shed and the chicken coop to the spring house to chill. A small apple orchard was an important part of the ranch agriculture. Maintaining equipment, repairing items, and shoeing horses made the blacksmith shop a necessity. In the corrals, livestock were branded and separated for sale.

Corral at Lockhart Ranch (NPS).

Today, the ranch landscape appears much as it did when Caroline Lockhart was living there. It provides visitors with a window to the operations of a ranch in the Dryhead area during the first part of the 1900s and an introduction to the spirited woman who embraced this part of the country in both her life and her writing.

An ornamental willow gate hangs partially open, welcoming visitors to the Lockhart Ranch (NPS).

Sources and More

- Caroline Lockhart and the Caroline Lockhart Ranch, Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area

- Caroline Lockhart Ranch: National Register of Historic Places Nomination

- Historic Ranches of Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area

- Caroline Lockhart Ranch, Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area (Draft, 1981)

- Images of Lockhart Ranch

- Artist-in-Residence Program at Bighorn Canyon

- More about NPS cultural landscapes

This month, we are exploring a few of the NPS cultural landscapes associated with writers and writing. Catch any you missed or add your own favorites with #literarylandscapes

Post link

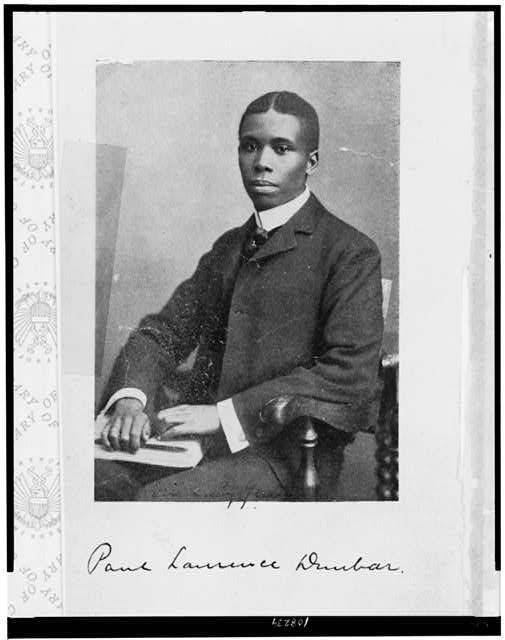

Literary Landscapes: Paul Laurence Dunbar

There are writers that find stories to write about, and there are stories that find a writer to tell them. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) can easily be characterized as the later. Born in Dayton, Ohio, to parents that endured slavery, Dunbar attended public schools and discovered a love for sharing wisdom and words. He was involved with the school newspaper and active in both debate and literacy societies. It was in school that Paul first became acquainted with Orville Wright, of the famed Wright Brothers, who eventually would print the newspaper that Paul published and edited for the African American community of west Dayton.

After high school Paul secured employment in Dayton operating an elevator, while he continued to write short stories and poems. In 1892, he was asked to speak at the Western Association of Writers in Dayton, where he met poet James Newton Matthews. Matthews encouraged Paul to publish his first collection of poetry, Oak and Ivy, in 1893. His writing continued to garner high levels of praise and expose him to influential people such as Frederick Douglass andCol. Charles Young.

Paul Laurence Dunbar portrait, 1905 (Illus. in: Lyrics of sunshine and shadow / by Paul Laurence Dunbar. New York : Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905, frontispiece. Source: Library of Congress).

Paul’s life was marked by the successes and pitfalls that sometimes afflict artists. He toured the United States and Great Britain delivering public readings of his work. He published a newspaper and wrote novels, plays, and song lyrics, finding accomplishment in his own right while also advocating for the rights of others. He found camaraderie with fellow poets and scholars and, after a courtship by letter, eloped with poet Alice Ruth Moore in 1898. His diagnosis with tuberculosis in 1899 and resulting self-medication regime with alcohol lead to his separation from Ruth in 1902 and his return to his mother’s home, where he died in 1906.

The Paul Laurence Dunbar House Historic Site was the first state memorial in Ohio dedicated to an African American (in 1936) (NPS).

Dunbar’s legacy lives on for the world through his literary works and in the sites that commemorate and interpret his accomplishments. Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry influenced the 1920s Harlem Renaissance writers James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, and Claude McKay, and and continues to influence American literature. As an African American writer, he shared the African American experience of his time to the world and became a voice that spoke of humanity and not stereotypes.

“I did once want to be a lawyer, but that ambition has long since died out before the all-absorbing desire to be a worthy singer of the songs of God and nature. To be able to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that after all we are more human than African.”

– July 13, 1895, Dunbar letter to Dr. Henry Tobey

Paul Laurence Dunbar Home

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s family home, purchased by his mother Matilda in 1904, is located at 219 N. Paul Laurence Dunbar Street (formerly N. Summit) in Dayton, Ohio. After his passing in 1906, Paul’s mother maintained the home in memory of her son and his accomplishments until her death in 1934.

The state of Ohio purchased the home, opening it to the public in 1938 as a house museum. The site is significant for its association with Dunbar and was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1962 - the first in recognition of an African American individual. Today, the site remains owned and managed by the state of Ohio and is jointly managed by National Park Service staff and the organization Dayton History. In 1992, the 0.2 acre property became part of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park.

The NPS also interprets Paul Laurence Dunbar life and accomplishments at the Wright-Dunbar Interpretative Center, providing photographsandwritten works of Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Carriage House/Garage at Dunbar House (NPS / MWRO).

Stay Tuned:

Historic Structure Report and Cultural Landscape Report for the Paul Laurence Dunbar Home

The National Park Service is currently preparing technical guidance for management of the site, in the form of a Historic Structures Report and Cultural Landscape Report (release estimated in 2020). This document will guide the property’s physical treatment to ensure it retains integrity for future generations to enjoy.

Learn More

- Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park

- Dunbar Historic District - National Register of Historic Places nomination, National Archives

- West Third Street Historic District Cultural Landscape Inventory - The district is tangentially associated with internationally renowned, African‑American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Dunbar was raised in a home just outside of the district.

- More about NPS cultural landscapes

This month, we are exploring a few of the NPS cultural landscapes associated with writers and writing. Catch any you missed or add your own favorites with #literarylandscapes

Post link

Landscapes of Literature: Frederick Douglass at Cedar Hill

At the Washington, D.C. home where Frederick Douglass lived from 1877 until his death in 1895, his relationships to language and to the landscape continue to come alive.

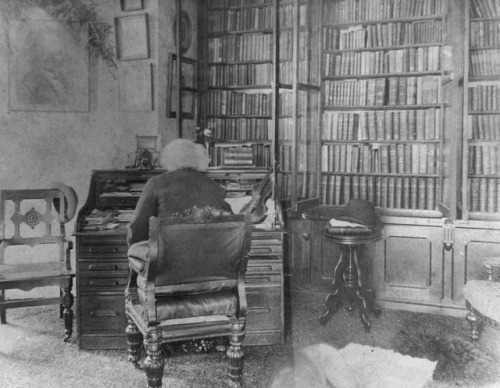

In the home known as Cedar Hill, bookcases line several walls of thelibraryaround the heavy wooden desk where Douglass read and wrote.

What books and booklets were in Frederick Douglass’s collection? Find a list of items in the NPS collection.

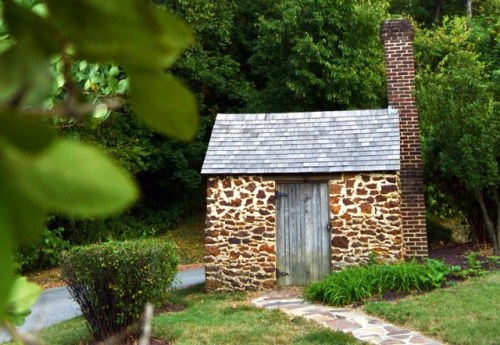

A walkway from the back of the house leads to a cozy windowless retreat, where Douglass kept a second desk filled with books and paper to write, read, and quietly contemplate. He called the structure the “Growlery,” a title used by characters of several Dickens novels to describe “a retreat for times of ill humour.” In the comfortable sanctuary of his Growlery, Douglass was able to study and write in peace. Once draped in vines and surrounded by fragrant shrubs, the structure is also thought to have fulfilled Douglass’s desire to work in a natural setting.

Photograph taken in the 1930s looking south from the historic house. Frederick Douglass’s Growlery (left) and barn (right) are visible, and a clothesline stretches between two trees over the backyard (NPS / Frederick Douglass National Historic Site).

Every year, the NPS hosts an oratorical contest in the auditorium at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site for students in grades 1-12. The goal of the contest is for students to experience the same transformative power of language that Frederick Douglass experienced as a young man.

This year’s contest will be held on December 6-7, 2019, and students from across the country are invited to apply.

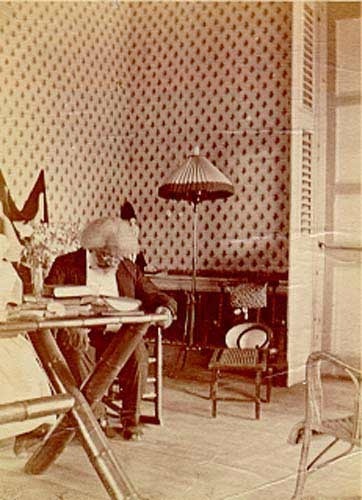

The house and surroundings of Cedar Hill, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (NPS).

Discover More

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site website

- Cedar Hill: Frederick Douglass’s Rustic Sanctuary

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site Cultural Landscape Inventory

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site Landscape Preservation Maintenance Plan

Additional image information can be found in NPGallery.

This month, we are exploring a few of the NPS cultural landscapes associated with writers and writing. Catch any you missed or add your own favorites with #literarylandscapes

Post link

For anyone who understands some German: this is a classic, early defence of the biologically diverse and beautifully sweet, traditionally tended European cultural landscape, and a cry of outrage against the destruction, disintegration and dismemberment of an ancient and rich nature, sacrificed on the altar of profit and ignorance.