#quaternary

Global late Quaternary [132,000 to 1,000 years ago] Megafauna Extinctions linked to humans, not climate change

Christopher Sandom, Søren Faurby, Brody Sandel and Jens-Christian Svenning (Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Denmark)

— Proceedings of the Royal Society / Biological Sciences, 22 July 2014AbstractThe late Quaternary megafauna extinction was a severe global-scale event. Two factors, climate change and modern humans, have received broad support as the primary drivers, but their absolute and relative importance remains controversial. …

We present, to our knowledge, the first global analysis of this extinction based on comprehensive country-level data on the geographical distribution of all large mammal species (more than or equal to 10 kg) that have gone globally or continentally extinct between the beginning of the Last Interglacial at 132 000 years BP and the late Holocene 1000 years BP, testing the relative roles played by glacial–interglacial climate change and humans.

We show that the severity of extinction is strongly tied to hominin palaeobiogeography, with at most a weak, Eurasia-specific link to climate change. …

IMAGE Global maps of late Quaternary [a, b] large mammal extinction severity, [c] hominin palaeobiogeography, [d] temperature anomaly and [e] precipitation velocity. [More detail here…]

Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change is an open access article.

Post link

American Mastodon – Late Miocene-Late Pleistocene (5.3-0.011 Ma)

Welcome, one and all, to a new feature on the blog, where I listen to music and review it! Today’s band is Mastodon, who I think is from Scandinavia? I dunno, I listened to one of their albums once and it was alright. 7/10. Join us tomorrow for a review of Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer!

But really, today’s animal is the mastodon. Specifically, M. americanum, the American mastodon. This is the youngest animal we’ve talked about so far, living from the late Miocene all the way to the end of the Pleistocene, about 10-11,000 years ago. It was first discovered in New York in 1705, a hundred years before paleontology proper was even an established science.

It lived all over North America during the last glacial period, and lived and looked much like an elephant. There were some key differences that can help you identify a mastodon from a mammoth or an elephant. They were stockier, with shorter legs and bigger muscles. Their tusks were really something, around 8 feet (5 meters) long. That’s longer than your modern elephants’ tusks, but shorter than a mammoth’s. They also had smaller ears than their modern cousins, to conserve heat. Modern elephants have such big floppy ears to keep cool, which mastodons absolutely did not need to do.

Where, oh where, did the mastodon go? It was one of the animals implicated in Quaternary extinction, which was when a bunch of big animals died out at the end of the last glacial period, for a lot of different reasons. Some animals stump us with how they managed to get wiped out, but we have a very likely suspect for mastodons.

This would normally be the part where I describe the suspect in vague terms and eventually reveal the suspect with the expectation that you’d be all like “Oh shit!” But I think you know where I’m going with this so I’m gonna cut right to it. It’s people. People probably killed mastodons to death. Paleo-indian people arrived in the Americas 13,000 years ago, and, well, we munched down on them and they went extinct.

Do you guys like taxonomy? Because I do! Taxonomy is the sorting system we use for living things, based on their relation to each other. It deals with assigning names and classifications to animals. The old mantra you had to memorize in school, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, etc., that’s taxonomy. It’s a million times more jumbled and complicated than I was led to believe initially, but I learned some fun things about Mastodon taxonomy while researching it.

Mastodons aren’t as closely-related to elephants as mammoths are. Mammoths, for reference, are really closely-related to modern elephants. In fact, they’re more closely-related to Asian elephants than both species of African elephant. They were essentially fluffier elephants. Mastodons, though, diverged way earlier, splitting around 38 million years ago. Wack.

You may have also noticed I’m not italicizing or capitalizing “mastodon,” like I do with every other animal I’ve talked about so far. That’s because “mastodon” isn’t the genus name for this animal. It used to be, though. There’s a rule in taxonomy, where the first name given to an animal always wins out. If a genus turns out to be synonymous with another, that animal’s name changes to the older one. That’s why Brontosaurus is called Apatosaurus now. Well, there’s more to that, but let’s stay out of that for now.

This animal was given the name “Mastodon” in 1817. Buuuuuuut, scientific writer Robert Kerr had named it Mammut americanum in 1792, so that name took priority, so its official genus is Mammut. People thought “mastodon” sounded better, though (even though it means “nipple tooth…”) and used it as an informal name, so that’s what it’s known by most popularly. It’s not “wrong” to call it mastodon, in the same way it’s not wrong to call an Equus a horse. It’s just not its genus name.

That does it for today’s taxonomy lesson. I liked mastodons as a kid, but let’s be real, who didn’t? Ice age animals are really cool, and I’m willing to bet there are very few children who saw something like this in a book and said “Eh, whatever.” Elephants are cool, so taking something like it, covering it in fur and giving it bigger tusks and saying “It’s not here anymore” makes them even more exciting. I talked about mastodons today because so far, I haven’t really given Cenozoic mammals enough attention. I also really wanted to practice drawing mammals because I’m bad at it.

Au revoir! I haven’t decided what the next animal will be, but expect something decidedly Mesozoic.

Post link

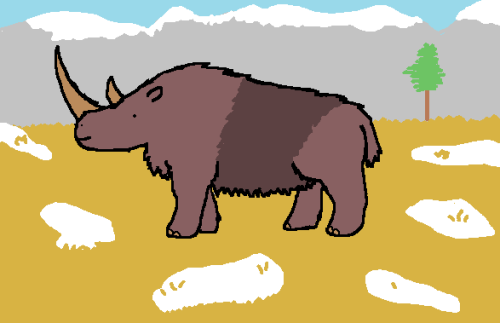

Woolly Rhinoceros – Late Pliocene-Late Pleistocene (3.6-0.01 Ma)

We’re getting iconic again, and talking about yet another ice age megafauna. This is the woolly rhinoceros, the best rhino ever. It might seem like a pretty basic animal, just a fluffy rhino. But, like most of the big ice age mammals, we have a comprehensive knowledge of this animal, from its appearance to its lifestyle to even its genetics.

Like with the mastodon, ‘woolly rhinoceros’ is a common name. Its scientific name is Coelodonta antiquitatis, which means ‘old hollow tooth.’ If that sounds kind of bland, that’s because it was named in 1807, and was one of the first extinct animals described, although it had been known as the woolly rhinoceros for a while before being formally named. Woolly rhinos evolved on the Tibetan plateau at the end of the Pliocene. When the Pleistocene began and the earth grew colder, woolly rhinos spread, migrating all across Eurasia. They were the most widespread and successful species of rhinoceros to ever live, and their remains are pretty common. Along with a lotof skeletal remains, a few frozen specimens have been found in Siberia, with flesh and even fur intact. Because of that, we’ve been able to study their DNA and learn that their closest living relative is the Sumatran rhino.

Like the rhinos we know, love, and desperately try to protect today, these boys had horns. Two of them. One really big one on the tip of the snout, and a smaller one between the eyes. When these horns were first discovered, they were thought to be the talons of a giant bird, but now we know they belonged to a rhino adapted to life in the cold. The horns were used the same way any rhino uses its horn, for defense and as a mating display, but also used them to clear snow from the ground as they looked for something to eat. They were mostly solitary animals, although they sometimes traveled in groups of a few individuals.

Although they sported thick, shaggy pelts and other adaptations for the cold, woolly rhinos were perfectly capable of living in warmer climates, and didn’t die off because the earth got warmer, like we previously thought. They were generalist herbivores, and while their populations were certainly affected by the end of the ice age, many of them carried on business as usual. While it’s hard to say what exactly drove a prehistoric animal to extinction, generally, we think human hunters are to blame. They valued woolly rhinos for their meat and thick pelts, and since early humans had no idea about abstract ecological concepts like extinction, they probably hunted them until they stopped finding them.

It kind of sucks that here we are, thousands of years later, still killing all the rhinos. Except now we just kind of do it for fun, and we really should know better.

I mentioned woolly rhino DNA, and there’s more to say about that. Just before woolly rhinos went extinct, there’s evidence for a genetic bottleneck. A genetic bottleneck (also called a population bottleneck) happens when a population is heavily reduced, leaving only a few members. This cuts down the genetic diversity down accordingly. Genetic diversity is the key to survival of a species, and in a bottleneck situation, this diversity is limited. This makes it more difficult for the population to adapt, making them more vulnerable to extinction. Small population size often leads to inbreeding in severe bottleneck scenarios, which causes negative mutations. These mutations can’t be selected against, because there are no genetic alternatives, and eventually can pile up until the population spirals to extinction.

That being said, bottlenecks aren’t necessarily a death sentence for a population. Several other animals have been able to bounce back from them in the past. That includes our own Australopithecine ancestors about 2 million years ago, and it’s been suggested Homo erectus experienced one or two as well. There are still repercussions to such an event, though. Diversity builds up very slowly, and it can take a long, long time to recover even a fraction of that former diversity. Case in point, humans are still experiencing aftershocks of our ancestral bottleneck. As a species, we have infamously low genetic diversity, to the point that there are several other subspecies with more diversity than all of the human genome put together.

Only tangentially related, but this is why eugenics is an inherently unevolutionary idea. The ideal of the “master race” calls for the elimination of every single other characteristic, thus shrinking our already minuscule gene pool. All this would do is make Homo sapiens significantly weaker, especially in the long-run.

Back to our friend the woolly rhino, there’s evidence for a bottleneck in their history. Many specimens from just before the woolly rhino went extinct share an unusual feature. Their last neck vertebra has a pair of holes where ribs would fit. The genes responsible for cervical ribs are also linked with juvenile leukemia and a host of birth defects. A combination of overhunting and the recession of ice age glaciers likely shrank their populations, and if our ancestors didn’t finish them off, the rampant diseas and birth defects likely did. We’ve seen a similar pattern in mammoths, too.

I swear, I’m going to say everything there is to say about mammoths before I even get around to drawing one.

On a more charming note, Woolly rhinos were a popular subject of cave paintings. These works of art have been found all along their range, most famously in the Chauvet cave in France. In a lot of these paintings, the rhinos are shown with a band of dark fur on their midsection. I decided to take some advice from my forebears and add that to my own drawing. Thousands of years later, and we’re still here, painting woolly rhinos. Except I’m doing it on a computer and there’s a lot more guesswork involved.

Woolly rhinos are one of the most iconic prehistoric mammals, and have appeared in all sorts of media. If you’re a paleontology enthusiast, I probably don’t even need to tell you where you’ve seen one. For me, the first thing that comes to mind is the sixth episode of Walking with Beasts, “Mammoth Journey.” Beastsreally was the passion project of the Walking with team, and it really shows in the finale. It’s a beautiful snapshot of Pleistocene life, with our own ancestors playing second fiddle to a herd of mammoths. Like with the rest of the Walking with series, the CGI and some of the science hasn’t aged perfectly, but a documentary has yet to match it in aesthetic presentation, if you ask me. It simultaneously feels like the falling of the last curtain on prehistory, and the prologue to our own story. Even though the woolly rhino is only a minor player in the episode, it left a lasting impression on me as a kid, and I spent a lot of time drawing them when I was supposed to be paying attention in school.

While I could probably gush about Walking with Beasts for another few hundred words, it’s late, and I’m going to close off the post before it gets too off-topic.

P.S. I can’t promise that every drawing will have a background now, I drew this guy a little on the small side and wanted to spice the drawing up a little bit. The backgrounds are definitely fun to draw, though…

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

![mucholderthen: Global late Quaternary [132,000 to 1,000 years ago] Megafauna Extinctions linked to mucholderthen: Global late Quaternary [132,000 to 1,000 years ago] Megafauna Extinctions linked to](https://64.media.tumblr.com/104acfb5a9a09f60a9a4e69dfbe911da/tumblr_n8s612mmnq1rhb9f5o2_r1_500.jpg)