#pliocene

Grinning tun (sea snail) / CAS-G 60811

Scientific name: Malea ringens

Locality:Baja California, Mexico

Age:Pliocene

Department:Invertebrate Zoology & Geology, image © California Academy of Sciences

Post link

Pachycrocuta - The Giant Hyena

Mounted specimen from the Zhoukoudian Museum, Beijing.

Reconstruction by Mauricio Antón

When: Pliocene to Pleistocene (~ 5 million to .5 million years ago)

Where: Europe, Asia, and Africa

What:Pachycrocutais a prehistoric member of the Hyaenidae. Today hyenas are restricted to Africa and western Asia, but their fossil record has revealed they were once much more wide spread. Pachycrocuta has been found in Africa and Asia, but most specimens have been found in Europe, with many localities in the Iberian Peninsula. The largest species was Pachycrocuta brevirostris, which stood over 3 and a half feet (~100 cm) at the shoulder and is estimated to have weighed over 400 lbs (190 kg). This makes it about the size of a modern lioness! Cave deposits in both Spain and China have revealed multiple almost complete skeletons, suggesting that these animals lived in packs and utilized these caves as their dens.

As Pachycrocuta is even more heavyset and adapted for bone crunching than the living bone-crunching hyenas, it has been suggested that this fossil form was even more dependent on scavenging kills than living species. But there really is not much evidence to pack this up other than thought-experiments. As it appears that some large cat species were displaced when Pachycrocuta moved into their ranges, it is more likely it was a direct hunter that would take advantage of pre-killed remains when it could drive away other predators. Like 99% of carnivores today. The predator/scavenger divide is really not a fast or hard line at all. Even more evidence of hunting comes from the remains of interactions between PachycrocutaandHomo errectus. These two species overlapped and bones of our poor relative have been found in Pachycrocuta dens in China!

Post link

Sand dollar (Anorthoscutum interlineatum) fossil

Pliocene epoch, found near Pacifica, CA

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

South America//Pliocene (~2 million years ago) // Sparassodonta//image source

While it appears to be a sabre-toothed cat like Smilodon, Thylacosmilus was actually a marsupial (or at least a very close relative of them), making it a prime example of convergent evolution.

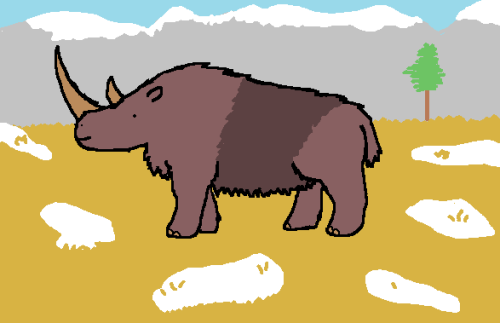

Woolly Rhinoceros – Late Pliocene-Late Pleistocene (3.6-0.01 Ma)

We’re getting iconic again, and talking about yet another ice age megafauna. This is the woolly rhinoceros, the best rhino ever. It might seem like a pretty basic animal, just a fluffy rhino. But, like most of the big ice age mammals, we have a comprehensive knowledge of this animal, from its appearance to its lifestyle to even its genetics.

Like with the mastodon, ‘woolly rhinoceros’ is a common name. Its scientific name is Coelodonta antiquitatis, which means ‘old hollow tooth.’ If that sounds kind of bland, that’s because it was named in 1807, and was one of the first extinct animals described, although it had been known as the woolly rhinoceros for a while before being formally named. Woolly rhinos evolved on the Tibetan plateau at the end of the Pliocene. When the Pleistocene began and the earth grew colder, woolly rhinos spread, migrating all across Eurasia. They were the most widespread and successful species of rhinoceros to ever live, and their remains are pretty common. Along with a lotof skeletal remains, a few frozen specimens have been found in Siberia, with flesh and even fur intact. Because of that, we’ve been able to study their DNA and learn that their closest living relative is the Sumatran rhino.

Like the rhinos we know, love, and desperately try to protect today, these boys had horns. Two of them. One really big one on the tip of the snout, and a smaller one between the eyes. When these horns were first discovered, they were thought to be the talons of a giant bird, but now we know they belonged to a rhino adapted to life in the cold. The horns were used the same way any rhino uses its horn, for defense and as a mating display, but also used them to clear snow from the ground as they looked for something to eat. They were mostly solitary animals, although they sometimes traveled in groups of a few individuals.

Although they sported thick, shaggy pelts and other adaptations for the cold, woolly rhinos were perfectly capable of living in warmer climates, and didn’t die off because the earth got warmer, like we previously thought. They were generalist herbivores, and while their populations were certainly affected by the end of the ice age, many of them carried on business as usual. While it’s hard to say what exactly drove a prehistoric animal to extinction, generally, we think human hunters are to blame. They valued woolly rhinos for their meat and thick pelts, and since early humans had no idea about abstract ecological concepts like extinction, they probably hunted them until they stopped finding them.

It kind of sucks that here we are, thousands of years later, still killing all the rhinos. Except now we just kind of do it for fun, and we really should know better.

I mentioned woolly rhino DNA, and there’s more to say about that. Just before woolly rhinos went extinct, there’s evidence for a genetic bottleneck. A genetic bottleneck (also called a population bottleneck) happens when a population is heavily reduced, leaving only a few members. This cuts down the genetic diversity down accordingly. Genetic diversity is the key to survival of a species, and in a bottleneck situation, this diversity is limited. This makes it more difficult for the population to adapt, making them more vulnerable to extinction. Small population size often leads to inbreeding in severe bottleneck scenarios, which causes negative mutations. These mutations can’t be selected against, because there are no genetic alternatives, and eventually can pile up until the population spirals to extinction.

That being said, bottlenecks aren’t necessarily a death sentence for a population. Several other animals have been able to bounce back from them in the past. That includes our own Australopithecine ancestors about 2 million years ago, and it’s been suggested Homo erectus experienced one or two as well. There are still repercussions to such an event, though. Diversity builds up very slowly, and it can take a long, long time to recover even a fraction of that former diversity. Case in point, humans are still experiencing aftershocks of our ancestral bottleneck. As a species, we have infamously low genetic diversity, to the point that there are several other subspecies with more diversity than all of the human genome put together.

Only tangentially related, but this is why eugenics is an inherently unevolutionary idea. The ideal of the “master race” calls for the elimination of every single other characteristic, thus shrinking our already minuscule gene pool. All this would do is make Homo sapiens significantly weaker, especially in the long-run.

Back to our friend the woolly rhino, there’s evidence for a bottleneck in their history. Many specimens from just before the woolly rhino went extinct share an unusual feature. Their last neck vertebra has a pair of holes where ribs would fit. The genes responsible for cervical ribs are also linked with juvenile leukemia and a host of birth defects. A combination of overhunting and the recession of ice age glaciers likely shrank their populations, and if our ancestors didn’t finish them off, the rampant diseas and birth defects likely did. We’ve seen a similar pattern in mammoths, too.

I swear, I’m going to say everything there is to say about mammoths before I even get around to drawing one.

On a more charming note, Woolly rhinos were a popular subject of cave paintings. These works of art have been found all along their range, most famously in the Chauvet cave in France. In a lot of these paintings, the rhinos are shown with a band of dark fur on their midsection. I decided to take some advice from my forebears and add that to my own drawing. Thousands of years later, and we’re still here, painting woolly rhinos. Except I’m doing it on a computer and there’s a lot more guesswork involved.

Woolly rhinos are one of the most iconic prehistoric mammals, and have appeared in all sorts of media. If you’re a paleontology enthusiast, I probably don’t even need to tell you where you’ve seen one. For me, the first thing that comes to mind is the sixth episode of Walking with Beasts, “Mammoth Journey.” Beastsreally was the passion project of the Walking with team, and it really shows in the finale. It’s a beautiful snapshot of Pleistocene life, with our own ancestors playing second fiddle to a herd of mammoths. Like with the rest of the Walking with series, the CGI and some of the science hasn’t aged perfectly, but a documentary has yet to match it in aesthetic presentation, if you ask me. It simultaneously feels like the falling of the last curtain on prehistory, and the prologue to our own story. Even though the woolly rhino is only a minor player in the episode, it left a lasting impression on me as a kid, and I spent a lot of time drawing them when I was supposed to be paying attention in school.

While I could probably gush about Walking with Beasts for another few hundred words, it’s late, and I’m going to close off the post before it gets too off-topic.

P.S. I can’t promise that every drawing will have a background now, I drew this guy a little on the small side and wanted to spice the drawing up a little bit. The backgrounds are definitely fun to draw, though…

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

Primelephas — Late Miocene- Early Pliocene (7-2 Ma)

I love elephants. I came out of hiatus just to say that. They’ve always been one of my favorite animals, and prehistoric proboscideans were one of the first paleontology topics I was really interested in as a kid. That probably shows, considering this is the third one I’ve drawn for this blog. BUT, this is the first true elephant to be featured here, and fittingly enough, its name means “first elephant.” Let’s pretend I did that on purpose and didn’t realize it as I was typing this just now.

Primelephas is pretty mysterious, even though it only went extinct pretty recently. We know a lot about the Miocene/Pliocene as a whole, but we only have a few remains of Primelephas. Those few remains have been found in Africa, although it was probably more widespread than that. It packed the setup we’ve come to expect of an elephant: A long, grasping trunk that doubled as a bendy straw, big, sturdy legs, and a stocky body. We can pretty reasonably assume it was mostly hairless, too, considering the environment it lived in. It sounds an awful lot like a modern elephant, doesn’t it? The main difference is the pair of tusks on the tip of its jaw. Elephant tusks come in all shapes and sizes, so I tried to draw this one with a pair of upper tusks that properly show off the bottom pair.

Oh, also, Primelephas is the common ancestor of three genera of elephant: Mammuthus,Elephas, and Loxodonta. I mention this because those are, in order, the Woolly Mammoth, the Asian Elephant, and the African Elephant. That’s why it looks so much like a modern elephant, because it’s only one step removed. The best part about the Cenozoic is how well we understand the taxonomy of the animals who live in it. Not to mention, cats evolved during the Cenozoic, and I personally find that very important.

If you don’t know elephant taxonomy (and I don’t blame you if you don’t), you might find it weird that 1) African and Asian elephants are different genera, I didn’t know that until recently, and, 2) the Woolly Mammoth shares such a recent common ancestor with them. The other furry proboscideans, the Mastodons, diverged from their modern cousins during the Oligocene, around 30 million years ago, so it would make sense if mammoths did that, too. Except, they didn’t, because there are no rules in biology. Here’s a chart showing the family tree of modern elephants. Like the last time I did one of these, it’s very simplified and only shows the stuff that’s relevant.

So, as you can see, mammoths are descended from Primelephas, just like modern elephants. Not only that, but mammoths are more closely-related to Asian elephants than Asian elephants are to African elephants. Considering mammoths evolved so recently from an ancestor who most likely only had sparse hair like a modern elephant, and considering just how close they are to Asian elephants, it’s very likely that heavier fur is a trait that’s relatively easy for natural selection to “turn on” or “turn off” in proboscideans. Also keep in mind this happened more than once, because Mastodons did it too. This is something we’ve studied pretty closely, and this is actually tapping on the window of a really cool subject that will have to be covered another day. For now, I have to crawl back into my hiatus cave and do some more research. I’ll see you all next week!

**********************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

Chalicotherium – Late Oligocene-Early Pliocene (28-3 Ma)

You know what? I’m bored of prehistoric animals. Starting today, I’m just gonna pull a Jurassic World and start making shit up. Here’s my OC, it’s a gorilla horse and its name is Steven.

Just kidding, this is a real animal. It’s not a particularly obscure one, so I probably didn’t fool a lot of you. Also, I’m bad at lying so that doesn’t help my case.

So, continuing with the theme of weird-ass mammals from the Cenozoic, we’re talking about Chalicotherium. What’s the deal with Chalicotherium? Every detail about it only makes it weirder. It was a knuckle-walking herbivore from Eurasia, with the head of a horse. Its forelimbs were elongated and tipped with long claws. Its hind limbs were shorter, and it probably spend a long time sitting back on them. Despite this, Chalicotherium was a peaceful animal. It used its claws to pull branches down and munch on soft vegetation. It probably walked on its knuckles to avoid wearing the claws down. Juveniles had incisors and canine teeth at the front of their jaw, like we do, but as they matured, the teeth fell out and weren’t replaced, leaving only the molars. When they were younger and smaller, they probably only had access to the tougher plants close to the ground. But as they matured and could reach higher plants, they no longer needed teeth for cutting and stripping leaves. Adult Chalicotherium were probably picky eaters. And since they were the tallest animals in their ecosystems, they could afford to be. As far as we know, there weren’t any other animals gunning for that good, good vegetation up there. Or at least, not animals that could reach it.

Chalicotherium was an odd-toed ungulate, and its closest living cousins are tapirs, horses, and rhinos. The Chalicothere family was long-lived, first evolving from small woodland types in the Eocene. Their ancestors probably looked a lot like early horses, chubby little animals with short toes. As grasslands became increasingly prevalent in the Cenozoic, Chalicotheres diverged into two groups: One that stayed in the woodlands and took care of business as usual, and another group that took advantage of this strange new ecosystem and populated the grasslands. Chalicotherium belonged to the latter. The family survived until surprisingly recently, with the most recent member living until about 700,000 years ago.

Depending on who you ask, Chalicotherium might even still be hanging around (DISCLAIMER: Almost certainly not). A Kenyan cryptid called the Nandi Bear has been speculated by some to be a Chalicothere, given the description of an animal with a sloped back and sharp claws. Although, the Nandi Bear is supposed to be a carnivore, so that doesn’t really vibe with our friend the Chalicotherium. According to local tradition, the Nandi Bear eats only the brains of its victims, and that’s definitely not what this animal was about. Chalicotherium just wanted to wander around and eat leaves. It wasn’t a violent animal. So yeah, it’s not true, but it’s fun to talk about.

I’ve wanted to draw Chalicotherium for a while. It’s such a bizarre animal, and I love the detail with which we can analyze the mammals of the Cenozoic. I first heard about this family from Walking with Beasts. I’ve kind of inadvertently covered most of the animals from “Land of Giants”. The first mammal I talked about was the star of that episode, Paraceratherium, and the last Cenozoic animal I discussed was an Entelodont. Oh well. I just think they’re neat.

Post link