#pleistocene

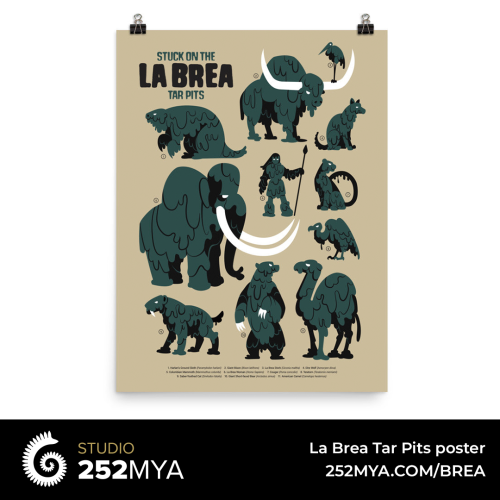

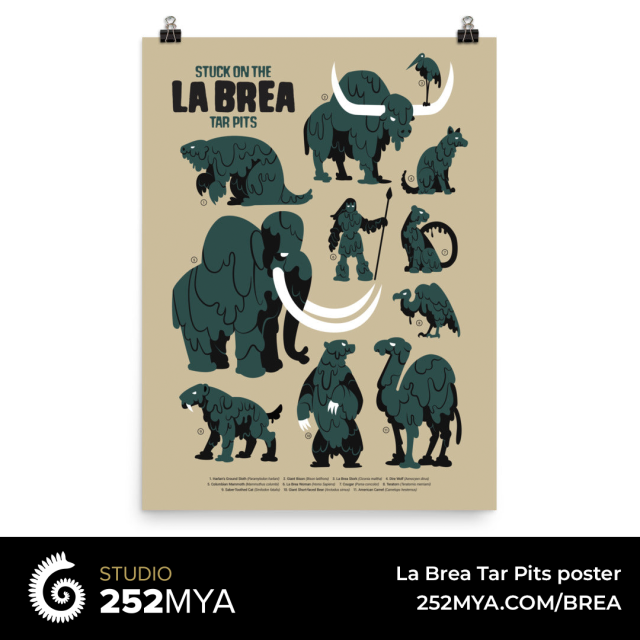

La Brea Tar Pits poster

Design by Greco Westermann

A poster featuring some noteworthy victims of the the La Brea Tar Pits. Mammoths, ground sloths, dire wolves and other animals from the last glaciar period that were unfortunate enough to get stuck in the tar.

sulc.us/brea

Design by Greco Westermann

Post link

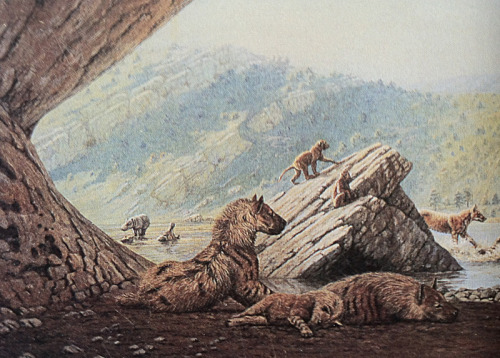

Dire wolf / CAS-G 61485

Scientific name: Canis dirus

Age: Pleistocene

Locality: California, USA, North America

Department: Invertebrate Zoology & Geology, image © California Academy of Sciences

Post link

Pachycrocuta - The Giant Hyena

Mounted specimen from the Zhoukoudian Museum, Beijing.

Reconstruction by Mauricio Antón

When: Pliocene to Pleistocene (~ 5 million to .5 million years ago)

Where: Europe, Asia, and Africa

What:Pachycrocutais a prehistoric member of the Hyaenidae. Today hyenas are restricted to Africa and western Asia, but their fossil record has revealed they were once much more wide spread. Pachycrocuta has been found in Africa and Asia, but most specimens have been found in Europe, with many localities in the Iberian Peninsula. The largest species was Pachycrocuta brevirostris, which stood over 3 and a half feet (~100 cm) at the shoulder and is estimated to have weighed over 400 lbs (190 kg). This makes it about the size of a modern lioness! Cave deposits in both Spain and China have revealed multiple almost complete skeletons, suggesting that these animals lived in packs and utilized these caves as their dens.

As Pachycrocuta is even more heavyset and adapted for bone crunching than the living bone-crunching hyenas, it has been suggested that this fossil form was even more dependent on scavenging kills than living species. But there really is not much evidence to pack this up other than thought-experiments. As it appears that some large cat species were displaced when Pachycrocuta moved into their ranges, it is more likely it was a direct hunter that would take advantage of pre-killed remains when it could drive away other predators. Like 99% of carnivores today. The predator/scavenger divide is really not a fast or hard line at all. Even more evidence of hunting comes from the remains of interactions between PachycrocutaandHomo errectus. These two species overlapped and bones of our poor relative have been found in Pachycrocuta dens in China!

Post link

Procoptodon - The giant short faced kangaroo

Mounted skeleton on display at Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Caves National Park, South Australia

Reconstruction by Peter Trusler.

When: Pleistocene (~ 2 million to 15,000 years ago)

Where: Throughout Australia

What:Procoptodon is a giant fossil kangaroo. Exactly how ‘giant’ it is has been a bit exaggerated, heights of up to 10 feet (~3 meters) have been reported, but this would have been its maximum height when it reared up fully on its hind legs, with its arms reaching up for high branches. Procoptodon was capable of this posture, but (like living kangaroos) it did not stand fully upright most of the time. In its normal feeding (and most everything else) poster it would have stood about 6.5 feet (~ 2 meters) tall; about the same height as the largest of the modern red kangaroos. Procoptodon was not the same size as these animals though, it was much more massive and would have been over twice the weight of a red kangaroo of equivalent height.

Procoptodon was very well adapted for the semiarid conditions that characterized much of Australia during the Pleistocene, but fossil remains have also been found in the more hospitable regions of prehistorical Australia. The marsupials of Australia are well known for their convergence evolution upon forms from other continents (such as the tasmanian tiger and the marsupial mole), but the kangaroo does not look like any placental mammal known. However, in terms of its lifestyle, the ecological niche that it inhabits, the group is convergent upon hoofed animals, such as deers! Procoptodon overlapped with human habitation of Australia, and it is thought some Aboriginal folktales are about this massive kangaroo.

Procoptodon is a member of the group Sthenurinae - the shortfaced kangaroos. As you probably guessed these kangaroos had much shorter snouts than the modern species of kangaroos. This group is completely extinct. It is one of the subgroups of the Macropodidae, the clade of marsupials that contains all kangaroos and wallabies, as well as a few other groups. It has been proposed that within the Macropodidae the closest living relative of Procoptodon is the Banded hare-wallaby, though this is not universally accepted.

In the prehistoric outback Procoptodon would have co-exsited with the largest marsupial of all time Diprodoton and was a hunted by the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. And the second link you can see this marsupial predator hunting a close relative of Procoptodon!

Post link

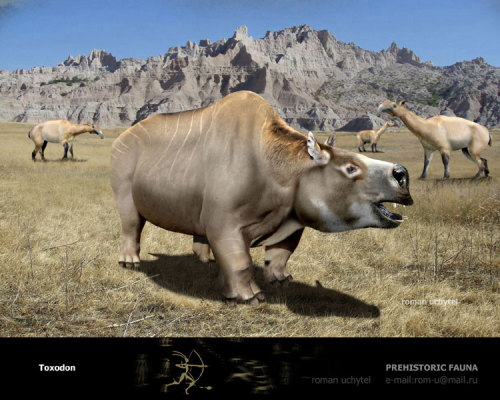

Toxodon

Mounted specimen on display at Harvard Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Roman Uchytel

When: Pleistocene (~2.6 million to 16,000 years ago)

Where: South America

What:Toxodon is another one of the large herbivorous animals that roamed over South America. Charles Darwin purchased the skull of the first Toxodon known to the Old World during his journey on the Beagle. This skull was sent back to England were Sir Richard Own described it and named the animal Toxodon - ‘bow teeth' based on the curving nature of its gigantic molars. Soon complete skeletons of this amazing animal were known. The first interpratations reconstructed Toxodon as a semi-aquatic animal, much like the modern hippo, but later studies of the limbs and teeth of speciemens show this was incorrect. Toxodon was more the analogue of today’s rhinos than a hippo, a fully terrestrial animal with teeth well adapted for grinding tough plants in somewhat arid environments. Some Toxodon specimens have been found associated with arrowheads, showing that the first people to emigrate into South America had contact with these animals, and appear to have hunted them.

Where does Toxodon fit into the tree of life? Like its contemporary Macrauchenia (which you can see in the background of the reconstruction), its relationship to living mammals is uncertain. It falls into the larger clade of Notoungulata, literally Southern Ungulates, but the placment of this group within placental mammals is highly uncertain. They maybe have a close relationship with animals in the group Afrotheria but research in mammalian systematics is only beginning to be able to evaluate that, and other hypotheses. So what is Toxodon? We just don’t know.

Post link

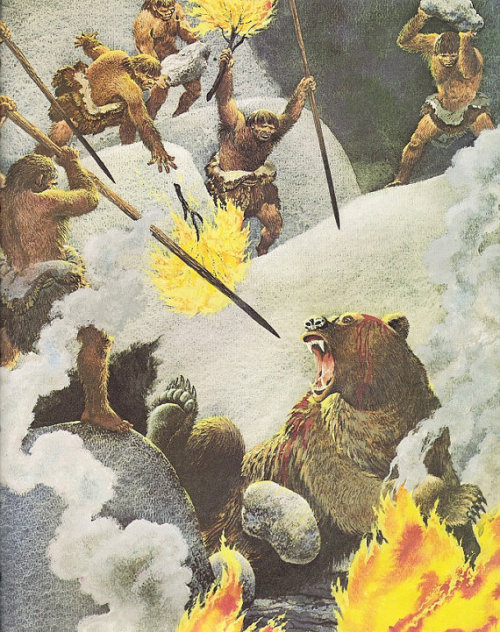

Neanderthals and cave bear, Rod Ruth, c. 1974

The cave is flooded with sound—the roar of the torches, the howls of the men, the cry of the bear, the clatter of the stones, the echoes off the walls. The smoke blinds, chokes, intensifies the noise and the violence.

The bear’s eyes glint from the flames. She is losing. Blood seeps through the fur of her head. One leg will not move as it should; a boulder crushed it. The cave was quiet and dark before these gibbering fire-holders came—the only warmth was her own, the only sound was her heartbeat. Then fire and stones and sticks rained down. At first it was confusing, now it is terrifying. Another rock strikes her and sparks cloud her vision. The cave feels small now, or rather, it feels as if it’s getting smaller, folding, slowly, steadily, finally, like a great eye closing to go to sleep.

Post link

Smilodon Attacking Wild Horses, Roy G. Krenkel

Death clutches at the horse in an emptiness. The horse feels naked here. All that lays below is earth, and all that rests above is sky, and vulnerability flows between the two. It is a lonely place. Though the hooves of its companions thunder nearby, the horse does not hear them, just its own heartbeat and the big cat’s breath and the last desperate drummings of its feet against the dirt.

Post link

Way to go, ground sloth, it’s not like he was using that tree as cover or anything.

Twitter|Facebook|Livestream|DeviantArt

Post link

OH MY GOD LOOK AT THIS POSTCARD FROM 1880 IN THE MANCHESTER MUSEUM ARCHIVES

“festive image of Pleistocene mammals”

“a rink in the glacial period”

THIS IMAGE HAS SINGLE-HANDEDLY PUT ME IN THE FESTIVE MOOD

MERRY CHRISTMAS

That’s a vibe

Winter fieldwork

Post link

George Church on Mammoths

George Church is a professor of Genetics at Harvard University and one of the world’s leading geneticists. He recently published a book with Ed Regis called Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves. Church and his team are using CRISPR, a gene editing technology, to insert parts of mammoth DNA into the Asian elephant genome. Ideally, this one day result in a whole population of cold-resistant, hairy pachyderms suited for life in the arctic–animals that are physically, behaviorally, and genetically very similar to the extinct woolly mammoth. This interview has been edited and condensed for length.

How is your lab hoping to make a mammoth embryo?

People go into the Siberian ice to get mammoth remains, and you can get broken DNA, and you can use a sequencing device to turn that into a computer data version of the mammoth genome. You put all the little parts together to make a complete mammoth genome, or you can take important parts of the genome and put them on an Asian elephant’s DNA. Then we put the sequence into an Asian elephant’s egg and get it to start multiplying.

In what ways will the mammoth be different from an elephant?

Reblogging my interview with George Church because mammoth resurrection is back in the news. I have to point out that, while cloning mammoths appears to be trending, not a lot has changed. Except, Church now says that he wouldn’t want to use an elephant to gestate a mammoth fetus, he’d want to use an artificial womb, if anyone ever invents one. Specifically, a womb large and effective enough to gestate a baby pachyderm for more than a year.

Should we?

Post link

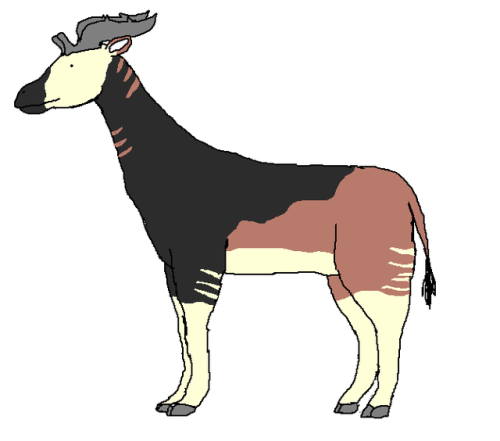

Sivatherium – Early Pliocene-Late Holocene (5-0.008 Ma)

Welcome back to Mammal Town! We’re talking about terrestrial animals again, and today’s featured landlubber is Sivatherium. The fun thing about Cenozoic mammals, especially when you get close to the current day, is that they tend to look generally similar to what we have today, but sometimes with a pinch of What the fuck. Sivatherium is a good example of that, and let’s talk about why:

Sivatherium lived very recently, maybe up to as recently as 8,000 years ago. Rock paintings of roughly that age have been found in India and the Sahara desert, and they look a whole lot like Sivatherium. As you can see, they were closely related to the giraffes and okapis of nowadays. Giraffids used to be a widespread, super diverse group before dwindling down to the two genera alive today. Sivatherium was like an okapi who spec’d hard into defensive traits. It was several feet taller and hella bulkier. It’s the largest giraffid known (even though giraffes are taller, they’re way more slender and lightly built, so they’re considered smaller), and maybe the biggest ruminant in the history of the universe.

Other than its size, the most defining features of Sivatherium are the pair of bone crests on its head. Sure, it has the classic giraffid forehead prongs, but also sported huge, heavy antlers. It must have had beefy shoulders, if it was going to be able to hold those antlers up. I want to be clear, this was an absolute unit of a giraffid. A built motherfucker.

This animal also has a bit of history to its research. When it was first classified in 1836, it was thought to be some kind of elephant. Then, it was thought to be something like a moose. While we were still figuring this guy out, it was generally thought that it had a fleshy trunk, or maybe a really prehensile lip, because the shape of its skull had room for muscles to move such a thing around. This idea was pretty much canned after we found out it was a giraffe cousin, though.

It’s generally assumed to have had a lip similar to giraffes and okapis because of a method called phylogenetic bracketing. What that means is, basically, we propose a trait in something extinct, usually something that doesn’t fossilize like a trunk. Then we look at its close relatives and ask, “Do they have it?” If the answer is “Yeah,” it’s pretty likely. If the answer is “Nah,” you can almost guarantee it’s not there. Since giraffes and okapis—both of which are REALLY close cousins to Sivatherium—don’t have a trunk or a really prehensile lip, it’s pretty likely it had a normal okapi face. And there’s nothing wrong with that. He’s still beautiful.

That’s a basic rundown of Sivatherium and… I guessan unplanned overview of phylogenetic bracketing. It’s always fun to see where these animals take me when I write about them. The next animal ought to be something much older, and maybe a little squishier. I don’t want to get too predictable here.

Post link

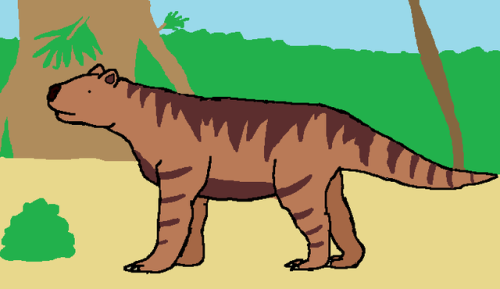

Thylacoleo carnifex – Early-late Pleistocene (1.6-0.46 Ma)

It’s been a long and very unannounced hiatus, but today is the day it ends. I’ve been extremely busy, but now I’m not. In the meantime, I learned about a fascinating little Australian named Thylacoleo carnifex. It’s commonly known as the marsupial lion, but is a lion in the same way a sea lion is. That is to say, it can hardly be considered a lion at all. It isa marsupial, though, and a member of the same order as kangaroos, koalas, and wombats. There are three total species of Thylacoleo, but T. carnifex is the best understood and most well-known, so I’ll talk about that one.

Australia has been disconnected from every other continent for more than 80 million years, splitting from Antarctica during the Late Cretaceous. During most of the Age of Mammals, metropolitan groups of mammals like cats, rodents, and ungulates (hoofed mammals), were unable to reach it. As a result, the marsupials and monotremes who were already there took over, and things got weird.

Thylacoleo lived during the Ice Age, but isn’t typically what we think of when it comes to Ice Age animals. Australia didn’t witness the huge ice sheets seen in North America and Eurasia, but colder worldwide climates meant Australia’s iconic outback was covered in temperate forests. Thylacoleo lived here. At roughly the size of a small tiger, it was the largest carnivorous mammal to ever live in Australia. It’s shaped roughly like the big cats dominating the rest of the Pleistocene world. This isn’t the only example of convergent evolution with Australian mammals. Palorchestes was another giant marsupial that evolved into something that looked like a tapir. In fact, certain body shapes pop up again and again among isolated ecosystems. Apparently, there is an optimal body plan when it comes to fulfilling certain roles.

ButThylacoleo has a few key differences from its distant feline cousins, and these give clues about its lifestyle. It had a stocky body and big, powerful forelimbs, along with a thick tail. It wasn’t chasing down prey at all, and was probably an ambush hunter that wrestled prey with its front limbs, using its tail for balance. Weirdly enough, it has a lot in common with Smilodon, the saber-tooth cat. Evolution really do be like that sometimes. But there’s something else about this animal, something best explained by showing you. So, now’s the part of the show where it sings us a soulful ballad and—

GOOD LORD WHAT IS HAPPENING IN THERE?

Now, mammals are famous for having weird teeth. Mammal teeth are weird enough that a whole lot of fossil mammals are… just teeth. But Thylacoleo is special. Its incisors were sharpened, acting like the canine teeth of other predatory mammals. Those big rectangular teeth acted like scissor blades for cutting meat and bone. They’re (very) elongated versions of teeth called carnassials. Most carnivorous mammals have a less wild version. If you look inside your dog’s mouth, they’re the two pairs of big, pointed teeth towards the back of their mouths. Cats have them too, but they’re a lot less pronounced.

Having weird-ass teeth like this means their hunting strategy was a little unorthodox. Big cats hunt by sinking their fangs into the neck of their prey, blocking its windpipe until it suffocates. Woof. Thylacoleo couldn’t really do that, thanks to its carnassials. Thylacoleo hunted its prey by crushing the windpipe and spinal cord of its prey with those mouth blades. It also had the strongest relative bite force of any mammal we know of, so it was pretty good at what it did.

So, what happened to the marsupial lion? It went extinct around 50,000 years ago, along with a lot of the other Australian megafauna. That’s probably not a coincidence. Thylacoleo was fantastic at bringing down large prey, but very poorly-adapted to hunting smaller animals. Such heavily specialized animals are often the first to go in extinction events. The Australian climate was beginning to shift as well, beginning to resemble modern Australia. This brought with it all the calamities, big and small, of climate change. Oh, and humans showed up around 60,000 years ago. There is evidence of interaction between Thylacoleo and Aboriginal Australians, in the form of cave paintings of a pouched carnivore. Aboriginal tradition also describes monsters and animals that may have been inspired by Thylacoleo. Methods of farming used by ancient humans may have further destroyed the forests Thylacoleo depended on for hunting, as well.

Thylacoleo is essential to understanding Ice Age Australia. It lived in an ecosystem that doesn’t really exist there anymore, and was specialized in hunting prey that mostly perished alongside it. It showcases both sides of island evolution: The unique traits, as well as the convergent ones. Its extinction marked the end of an era, one dominated by marsupials since the wake of the K-Pg impact event. Australia is still unique today, but there still isn’t a predator around quite like this one.

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

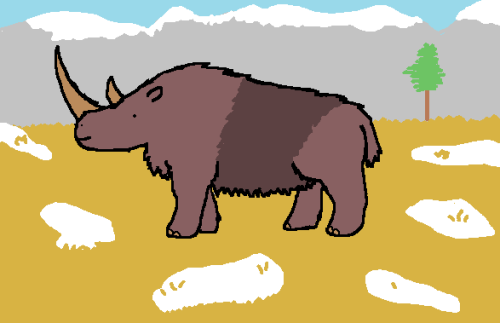

Woolly Rhinoceros – Late Pliocene-Late Pleistocene (3.6-0.01 Ma)

We’re getting iconic again, and talking about yet another ice age megafauna. This is the woolly rhinoceros, the best rhino ever. It might seem like a pretty basic animal, just a fluffy rhino. But, like most of the big ice age mammals, we have a comprehensive knowledge of this animal, from its appearance to its lifestyle to even its genetics.

Like with the mastodon, ‘woolly rhinoceros’ is a common name. Its scientific name is Coelodonta antiquitatis, which means ‘old hollow tooth.’ If that sounds kind of bland, that’s because it was named in 1807, and was one of the first extinct animals described, although it had been known as the woolly rhinoceros for a while before being formally named. Woolly rhinos evolved on the Tibetan plateau at the end of the Pliocene. When the Pleistocene began and the earth grew colder, woolly rhinos spread, migrating all across Eurasia. They were the most widespread and successful species of rhinoceros to ever live, and their remains are pretty common. Along with a lotof skeletal remains, a few frozen specimens have been found in Siberia, with flesh and even fur intact. Because of that, we’ve been able to study their DNA and learn that their closest living relative is the Sumatran rhino.

Like the rhinos we know, love, and desperately try to protect today, these boys had horns. Two of them. One really big one on the tip of the snout, and a smaller one between the eyes. When these horns were first discovered, they were thought to be the talons of a giant bird, but now we know they belonged to a rhino adapted to life in the cold. The horns were used the same way any rhino uses its horn, for defense and as a mating display, but also used them to clear snow from the ground as they looked for something to eat. They were mostly solitary animals, although they sometimes traveled in groups of a few individuals.

Although they sported thick, shaggy pelts and other adaptations for the cold, woolly rhinos were perfectly capable of living in warmer climates, and didn’t die off because the earth got warmer, like we previously thought. They were generalist herbivores, and while their populations were certainly affected by the end of the ice age, many of them carried on business as usual. While it’s hard to say what exactly drove a prehistoric animal to extinction, generally, we think human hunters are to blame. They valued woolly rhinos for their meat and thick pelts, and since early humans had no idea about abstract ecological concepts like extinction, they probably hunted them until they stopped finding them.

It kind of sucks that here we are, thousands of years later, still killing all the rhinos. Except now we just kind of do it for fun, and we really should know better.

I mentioned woolly rhino DNA, and there’s more to say about that. Just before woolly rhinos went extinct, there’s evidence for a genetic bottleneck. A genetic bottleneck (also called a population bottleneck) happens when a population is heavily reduced, leaving only a few members. This cuts down the genetic diversity down accordingly. Genetic diversity is the key to survival of a species, and in a bottleneck situation, this diversity is limited. This makes it more difficult for the population to adapt, making them more vulnerable to extinction. Small population size often leads to inbreeding in severe bottleneck scenarios, which causes negative mutations. These mutations can’t be selected against, because there are no genetic alternatives, and eventually can pile up until the population spirals to extinction.

That being said, bottlenecks aren’t necessarily a death sentence for a population. Several other animals have been able to bounce back from them in the past. That includes our own Australopithecine ancestors about 2 million years ago, and it’s been suggested Homo erectus experienced one or two as well. There are still repercussions to such an event, though. Diversity builds up very slowly, and it can take a long, long time to recover even a fraction of that former diversity. Case in point, humans are still experiencing aftershocks of our ancestral bottleneck. As a species, we have infamously low genetic diversity, to the point that there are several other subspecies with more diversity than all of the human genome put together.

Only tangentially related, but this is why eugenics is an inherently unevolutionary idea. The ideal of the “master race” calls for the elimination of every single other characteristic, thus shrinking our already minuscule gene pool. All this would do is make Homo sapiens significantly weaker, especially in the long-run.

Back to our friend the woolly rhino, there’s evidence for a bottleneck in their history. Many specimens from just before the woolly rhino went extinct share an unusual feature. Their last neck vertebra has a pair of holes where ribs would fit. The genes responsible for cervical ribs are also linked with juvenile leukemia and a host of birth defects. A combination of overhunting and the recession of ice age glaciers likely shrank their populations, and if our ancestors didn’t finish them off, the rampant diseas and birth defects likely did. We’ve seen a similar pattern in mammoths, too.

I swear, I’m going to say everything there is to say about mammoths before I even get around to drawing one.

On a more charming note, Woolly rhinos were a popular subject of cave paintings. These works of art have been found all along their range, most famously in the Chauvet cave in France. In a lot of these paintings, the rhinos are shown with a band of dark fur on their midsection. I decided to take some advice from my forebears and add that to my own drawing. Thousands of years later, and we’re still here, painting woolly rhinos. Except I’m doing it on a computer and there’s a lot more guesswork involved.

Woolly rhinos are one of the most iconic prehistoric mammals, and have appeared in all sorts of media. If you’re a paleontology enthusiast, I probably don’t even need to tell you where you’ve seen one. For me, the first thing that comes to mind is the sixth episode of Walking with Beasts, “Mammoth Journey.” Beastsreally was the passion project of the Walking with team, and it really shows in the finale. It’s a beautiful snapshot of Pleistocene life, with our own ancestors playing second fiddle to a herd of mammoths. Like with the rest of the Walking with series, the CGI and some of the science hasn’t aged perfectly, but a documentary has yet to match it in aesthetic presentation, if you ask me. It simultaneously feels like the falling of the last curtain on prehistory, and the prologue to our own story. Even though the woolly rhino is only a minor player in the episode, it left a lasting impression on me as a kid, and I spent a lot of time drawing them when I was supposed to be paying attention in school.

While I could probably gush about Walking with Beasts for another few hundred words, it’s late, and I’m going to close off the post before it gets too off-topic.

P.S. I can’t promise that every drawing will have a background now, I drew this guy a little on the small side and wanted to spice the drawing up a little bit. The backgrounds are definitely fun to draw, though…

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link