#romantic music

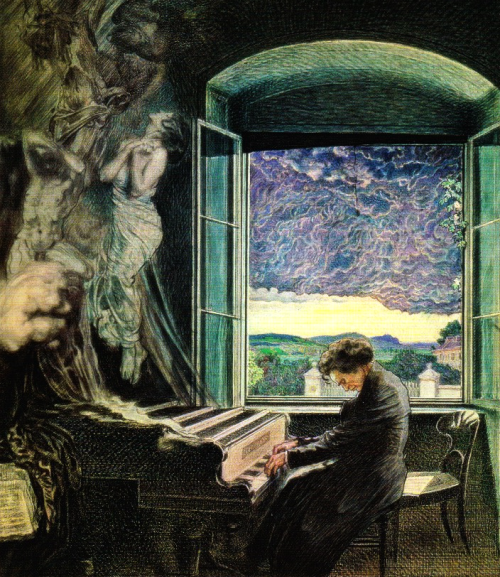

Allegory of the Genius of Beethoven by Sigmund Walter Hampel.

Allegorie des Genies Beethoven von Sigmund Walter Hampel.

Post link

Strauss - Symphonia Domestica (1903)

“What can be more serious than family life? I want the Symphonia domestica to be understood seriously.” For fun, friends will ask each other what their “guilty pleasure” music is, and usually I think “well, obviously none of my classical favorites count. what’s ‘guilty’ about classical music?” But that was me thinking with a kind of classical-superiority bias. There’s plenty of works that aren’t “great”, but are a lot of fun, for the sake of spectacle. In this case I’ll say that my recent 'guilty pleasure’ favorite is Richard Strauss’ last tone poem, the “Symphonia Domestica”. To me it kind of exemplifies reasons people would dislike late and post Romanticism. The “story” is a musical portrait of a daily life in a family. Specifically, Strauss’ family. He has a heroic theme for himself, the husband/father, a gorgeous Hollywood love theme for the wife/mother (the singer, Pauline), and the ferocious wailing of their crying baby. We hear the family having fun together, the baby crying, soothed by a lullaby (here quoting Mendelssohn’s Venetian Boat-Song op.19 no.6, another piece close to my heart), then an intimate scene when the parents are alone (another instance that made critics roll their eyes), then an argument or “merry dispute” in the form of a double fugue, with an over-the-top apotheosis of the themes. Filtering the model for the “traditional” family, an otherwise banal topic, with the sonic vocabulary of Wagner’s “Twilight of the Gods”, made a lot of audiences and critics roll their eyes. It also doesn’t help that the themes aren’t really transformed as much as they’re re-orchestrated. At the same time I think people are ignoring the Mozartian side of Strauss. This piece is silly, in good ways, and has charm and fun. I opened this post quoting Strauss about the music. Maybe it’s a good reminder that we can romanticize our own lives, and treat our daily struggles and interactions as being significant enough to be depicted with such lavishness. And that lavishness is why I enjoy this work, and many others by Strauss which I’m ok with admitting are “second rate” (as he said of himself, “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer.”) because of the shear sounds, textures, and colors he creates with the orchestra. Hans Richter poked fun at the baby’s depictions in this piece with “All the cataclysms of the downfall of the gods in burning Valhalla do not make a quarter of the noise of one Bavarian baby in his bath.” The intense orchestral noise here, the over-abundance, is what brings me back to Strauss again and again. I especially love the last five minutes of the finale, where the themes come back with more extravagant orchestration, and with a nod toward Haydn and Beethoven’s musical humor, the piece refuses to end!

Movements:

- Introduction and development of principal themes

2. Scherzo

3. Adagio

4. Finale

Jeanne-Louise Farrenc

( 31 May 1804 - 15 September 1875 )

Happy Birthday, Louise!

Brahms-Symphony no. 3 in F Major(1884)

Despite how often people say Brahms was a conservative (which is true to a point), I think a lot of people underestimate his intensity of expression. The volume, bombast, and sometimes theatrical or operatic drama, are all underscored by the more traditional minded attitude toward structure and making sure the musical components are “functioning” in a logical way. Take the old form, and make something new out of it. Brahms had preferred that view to the newer Romantic school of thought favoring free-form and new forms created by the musical ideas themselves. Because of that, Brahms will always be the old scruffy severe German looking down at you from his wizened beard. Tangential, but I’ve talked with people who don’t like Brahms and they seem to come from this popular image: “Old fashioned”, dull, too theoretical, no good melodies, and (one extreme opinion) not truly “artistic”. But if we ignore the baggage of academicism and the symphony as a serious genre for developing complex musical thoughts, we should be thrown at the edge of our seats from the sound of the orchestra, and the long emotional melodies that people say aren’t there. I’ll take a moment to be more personal: I was surprised to find out that I’d made blog posts about the other three Brahms symphonies, but not this one. It was the first one that I fell in love with way back in high school. I remember listening to it and imagining knights in armor and large gothic castles. Brahms would turn in his grave. I got the idea from the bold and majestic opening movement. It begins with a statement of F-Ab-F, standing for Brahms motto “Frie aber froh”, Free but Happy. Somewhat leaning toward the 19th century trend of cyclical works, this symphony’s opening idea comes back in later movements as well. The motto of free but happy seems to radiate strongest in this opening movement. My favorite moment here is when the music quiets down a bit and teh flutes and bassoons play a an arabesque-like wavy melody over the strings fragmenting the same material, growing into a loud and stormy proclamation with chromatic lines (a very “Romantic” sound from a ‘Classicist”). The andante builds out of a chorale theme introduced in the winds. This more pastoral sound reminds us that this was a “vacation” work written while he was staying by the Rheine in Wiesbaden. The next movement, despite the unassuming title ‘poco allegretto’, has one of the more gorgeous melodies Brahms had written. It sings out of the cello and is punctuated by longing harmonies. Typical of Brahms, these harmonies are written out through counterpoint of fragments based off the contour of the melody. The last movement brings back the heaviness of the opening through a modified sonata. In the minor, it opens with a long and somewhat bouncy melody that could be like a Bach fugue subject. The music builds up energy into more drama, before shifting right into the “happy” counter melody. You could imagine this theme coming back with golden brass chorales. Instead, despite the dizzying effects done with the themes, and the noisy development that doesn’t let up in tension, the piece starts to sizzle up in agitated strings. A soft chorale brings back the opening motif, and then the symphony sighs away into a soft F major chord.

Movements:

- Allegro con brio

- Andante

- Poco allegretto

- Allegro - Un poco sostenuto

Chopin-Variations in A, “Souvenir de Paganini”(1829)

Every now and then I fall into a listening rabbit hole where I explore music from one composer for a few days, sometimes spilling into weeks or months. Right now, I’m back with Chopin. Odd choice, because I’m already familiar with him, and there’s tons of works in my “to listen to” list that are gathering dust while I replay the same nocturnes again and again. Chopin was the first composer that got me into classical music, so maybe because of how stressful the world is to live in right now, I’m turning back to something comfortable and familiar. And despite the familiarity, some Chopin has been hitting my ears as if for the first time. This “souvenir” is a set of delicate variations on Paganini’s Carnaval of Venice. Instead of virtuosic scratching violin solos, we get Chopin’s delicate nocturne-style piano writing and compact variations over a simple repeating bass. A precursor to his later more elaborate Berceuse. And it’s probably the mix of being a charming melody with a simple harmony (I-V-V-I almost throughout) that got this piece stuck in my head. The earworm’s been living in my brain for three days, but I don’t mind too much. Each variation adds a new arabesque figure into the mix, new ornaments, glittering extra-notes, and baroque figurations. And the calmer atmosphere makes me feel like I’m listening to music that could go on forever, constantly playing around with the melody. Feeling like one of those summer afternoons you wish wouldn’t end.

Ogiński-Polonaise in a minor, “A Farewell to the Homeland” (unknown arrangement) (1794)

I’m not above using a Harry Potter reference, but remember when Hermione picked up that brick of a book and said she was doing some “light reading”? That’s how I feel carrying Alan Walker’s ~700 page biography “Fryderyk Chopin, A Life and Times” out of the library. The name Ogiński comes up in the early chapters on Chopin’s childhood compositions and performances. Prince Michał Ogiński was a diplomat, military leader, and national hero for late 18th/early 19th century Poland. He also composed polonaises for the piano, and this one “A Farewell to the Homeland” is the most popular. The impressionable Chopin was greatly influenced by this music. I was listening to this and struck by how much of a resemblance to his mature style is here…except this *isn’t* the original polonaise. I cannot find any information on this arrangement, but it is a lightly Chopin-ized version of the more simple original, with little ornamentations, modulations, and added voices. Unfortunately since this was my introduction to the piece, the original is somewhat disappointing (although, historically, more believable). Even with these post-Chopin elaborations, you can still hear the strong influence on Chopin’s style, and makes me wonder about the nature of a “piece” of music. Is this arrangement inauthentic for trying to recreate Chopin’s style? Or is it a loving performance of a traditional polonaise that tries to retroactively translate it into Chopin’s style because he defines the idiom of 19th century polonaise? It is a shame that I can’t find more information on who arranged this, and makes me think of a downside to the Internet where so much information is shared but can easily be severed from its source and be left to float around as a digital mystery. As far as I can tell, this youtube video is the only evidence of this arrangement existing. If anyone knows more, please reach out to me! The polonaise opens with a melancholic melody, and the phrase ends with a gorgeous sighing cadence. We jump up the keyboard a bit into a B section that features a very flashy, more Lisztian cadenza that even evokes cimbalom mallets. The trio is charming, bright, and more classical. It continues its homage to Chopin’s style by recreating military fanfare. I am disappointed that I’ve fallen in love with this obscure rendition of the work, where there are no other recordings and where it wrongfully presents itself as the 1794 Ogiński original. But at least this arrangement is its own act of composition, even while being derivative of Chopin’s ‘juvenile’ style (which despite using this word, is nowhere near “juvenile” in its musical brilliance).