#sacred twenty eight

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Nott and Rowle

Ergi, the Rowles called them

And sneered,

But the Notts only smiled

And wove on in silence.

They might be ergi,

but they were seiðmenn

And they would never be blót.

The common wizards and witches of Britain had their own version of a very muggle saying - out of the frying pan and into the fire. Theirs was a little… different. For it went like this:

Fleeing the Blacks

only to cross the Notts.

The Blacks were dangerous, but nine times out of ten you knew precisely where you stood with them - they wore their hearts on their sleeves. If you insulted them, you could rest assured they would curse you, probably using some obscure dark curse no one had heard of and things would be well. Mostly.

But if you crossed a Nott, you’d never know it. They merely smiled and continued as though nothing were wrong at all. Excessively well-bred, always courteous - haute ton. But once you had left, they would return home, still smiling, and take down an ancient distaff and spindle; magical objects passed down from generation to generation for each Nott versed in the magical art of Seiðr.

Magical Britain laughed at divination and called it a fuzzy art with no magical grounding, for charlatans and their ilk, and the Notts agreed with them. Crystal balls, tea leaves, reading sticks - amateurs. The future was what people made it, what a talented seiðmenn orseiðkonurcould make it. The future was whatever the Notts chose to weave on their tapestries. Each thread, carefully placed, turning thought into reality, fiction into non-fiction, lies into truth.

None knew this better than the Rowles. They had learnt firsthand, many centuries ago, that mocking the Notts - these students of Odin - came with a price. A blood price that might have been honor to those who paid it but was a blood price nonetheless.

The Rowles might have been warrior-shamans; berserkers invulnerable in battle; but the might of the sword or even crude magical power could not withstand the implacable weaving and reweaving of reality and fate that the Notts took part in. Theirs was deeper magic, darker magic, terrifying magic and when the Rowles and Notts came to England with the first of the Vikings to rule Scotland, they brought rumours of what the Notts could do to people when crossed and people fearedthem.Fearedthese mild mannered men and women who refused to let this new religion called Christianity and its sociopolitical order sway them; who failed to conform to the new order’s strict regimentation of gender and male and female occupations; who smiled when people spurned them and smiled even wider when their mockers were slowly ruined piece by piece.

So not a murmur was heard when Proserpina Nott, aged 16, took up the family seat in the Wizengamot in 1734 though she was the youngest of the Notts and had not yet finished her schooling. The Ministry kept mum when Tiresias Nott refused to use their curriculum when teaching divination and instead taught his pupils trance magic and weaving: the beginnings of Seiðr. Wizengamot members cast their eyes downwards when Isembardus Nott stood up to make speeches, lest he see the judgement in their eyes when he painted his face and persisted in wearing pompadour wigs in public (it was 1854). People turned the the other way when Cantankerus Nott, pureblood fanatic extraordinaire, put half his fortune into muggle stocks and bonds. And no one dared say a word when Charles Nott stood a little too close to Antinous Lestrange at Ministry press conferences.

No. Only the foolish with a death wish ever crossed the path of a Nott. For they would have their revenge, these children of Guðrún, protégés of Odin and their revenge would be cold, dark and terror-filled as the houses of Hel.

[Picture sources: Shadows on Parade by Nicol Vizioli, CALLE 20 by Jose Herrera, The Essence by Spencer Hansen, Norns Bruk, A Golden Thread by John Melhuish Strudwick, screencaps from Vikings and 1066: the Battle for Middle Earth]

Post link

The Sacred Twenty Eight: the Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Mulciber, Rosier and Malfoy. (3/3)

The Malfoys, to their dismay, were not even deemed worthy of an insulting gift. Pretenders, the Mulcibers called them and blithely dismissed them as being generally unworthy of a gift. Their lineage was not old enough - even though they could trace their line back all the way to the Merovingian dynasty at least (more than several other families they could name) - and they had no dedicated family craft or magical art to speak of. That they had risen from obscurity and become one of the most powerful families in wizarding Britan seemed to matter very little to the Mulcibers. Parasites, said the Mulcibers, for the Malfoys thrived on the little games people in power played with each other and not on any magical skill of their own.

Worse still, the Malfoys were rather new when one compared them to the other families of the Sacred Twenty Eight. They could not trace their family line back all the way into legend as so many of the other families could - indeed they did not waste their time brooding over long family trees of dubious veracity. They did not claim divinity as the Lestranges did, nor did they claim to be descendants of famous and powerful sorcerers and sorceresses. No. They wore their badge of services rendered to William the Conqueror with pride - and wizarding society bought it for the most part. After all, not many could boast of having rendered services of a personal and delicate nature to the country’s monarchs.

The Mulcibers, however, proved to be a tiresome spanner in the works of the Malfoys’ carefully crafted story. Unspecified services to William the Conqueror were nothing to boast of, they said. Sailing with William the Conqueror was no great deed in itself. For all they knew, the Malfoys might have been William’s hangsmen - in fact it was quite likely, given the Malfoy family’s reticence on the matter of the nature of these services. Neither were services rendered to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the First of England enough to make the Malfoys worthy in their eyes. Politics, the Mulcibers believed, was a game anyone with a modicum of sense could play and was not enough to make the Malfoys exceptional in their eyes.

Thus it was that the Malfoys had to remain content with those artifacts they seized from wizards indebted to them - need we mention the Weasleys were among one of the unlucky families to have lost their prized heirlooms to the Malfoys (forever a sticking point between the two families)? - all the while aware that families like the Blacks and Lestranges were quietly snickering at them when their backs were turned. Aware and unable to do anything, for a gift is a gift and cannot be forced out of the giver. The snubbed Malfoys simply had to make do with a second rate (but nonetheless very beautiful) family sword. Not forged by the Mulcibers.

Some things, the Malfoys acknowledged, to their shame, could not be bought with money.

Post link

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Mulciber, Rosier and Malfoy. (2/3)

Imagine the chagrin, then, of the Rosiers when their turn to receive a gift came round and they found themselves slighted by the choice of gift. Yet as the Mulcibers were quick to remind them in delicate terms, if it had not been for a favour they owed the Rosiers, the Mulcibers might have never chosen to give them anything at all. But since they were required, as a point of honour, to do so, they chose their gift very carefully indeed and made sure the Rosiers knew precisely what they thought of them.

A throne, they gave the Rosiers. To be precise, a crudely made throne of iron sheets, nailed together in the most rough fashion possible. It looked well enough - the Mulcibers could let their aesthetic sensibilities only be offended so far - but it was no crafty sword or delicate objet d'art. The message was quite clear. The Rosiers were extravagant, aye, but extravagance would never cover up their true nature - that is to say, a nature of the basest kind.

To add salt to the wound, the throne had no magical value at all. It was precisely what it seemed - an ordinary iron throne - and one that a Mulciber might have sold to a vain muggle nobleman for an exorbitant price. Of course, the Rosiers could not say a thing, for a gift is a gift and to shove it back in the Mulcibers’ faces when they had received it with such pomp and circumstance would come across as ungracious and boorish. Heaven help them, the Mulcibers already thought so poorly of them, it would hardly do to encourage the rest of the wizarding world to think of them in the same way.

So the Rosiers kept quiet and fumed quietly in their boots, cursing their ancestors for having had the misfortune to be imprudent, foolish and vain, and above all, for incurring the scorn of the Mulcibers.

Post link

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Mulciber, Rosier and Malfoy (1/3)

It is no mean feat to deliver a well-placed insult to one of the Pureblood families who make up that exclusive group known as the Sacred Twenty Eight.

To insult twoof these families and get away with it - well that takes extraordinary talent, particularly if the families concerned happen to be the Malfoys and the Rosiers. Both are proud families, rarely forgiving perceived slights against them.

Presumptious, the Mulcibers called them. They may have all sailed together with William the Conqueror, but the Mulcibers could tell you a thing or two about them. The Rosiers might be an old family, with a geneaology going all the way back to the early days of the Roman empire, but they were most assuredly Not Respectable. For one, they had boughttheir citizenship from Livia Augustus (the Mulcibers had earnedtheirs through extraordinary services rendered to the empire). For another, the Rosiers had always been involved in some scandal or the other - orgies, selling cases for pennies, plenty of by-blows, cheating at cards and all that sort of thing. Not at all the nobles they made themselves out to be.

The Malfoys, of course, were risible in their claim to greatness. The Rosier family, at least, was of note. The Malfoys were originally an obscure family, without renown at all, who won their lands in Wiltshire for services of a Most Delicate Nature rendered to the Conqueror. Services that almost certainly had nothing to do with prowess on the battle field or an ability to craft useful magical artifacts.

For that was the Mulcibers source of pride. They were an old, old family (old enough in lineage to rival even the Ollivanders who traced their line all the way back to the year 327 B.C.) of smiths , potioneers and alchemists whose metalworks were well known across the wizarding world even in the days when Rome was still a republic. Their fame was so widespread that even the muggles knew of the Mulcibers, but knew of them only as owners of excellent smithies with the best weaponry known to mankind. For wizards, however, the Mulcibers were far more than mere smiths (or even descendants of Vulcan as it may be) for to own an artifact forged by a Mulciber was the seal of highest approval, which stamped the wizard as one of truly great stock. One had arrivedwhen one was finally deemed worthy of having something crafted by a Mulciber.

Naturally, these artifacts were not lightly given to all and sundry. They could be purchased at a high price - but these were generally held to be of less value than those creations given as gifts to wizarding families. For each gift was made specifically for that family, drawing on what the Mulcibers thought of the family and how they thought they could aid them most. For the Lestranges, thrice-forged swords with runic inscriptions both for warding their wielders from harm and for killing effectively; for the Blacks, unmentionable artifacts (because of their highly dark nature, muttered their detractors); for the Notts, a distaff which spun pure gold wool; for the Prewetts, torcs which rendered them invulnerable to all but the darkest of dark curses; and so on and so forth. Even the Weasley family had once been given three daggers, which they had long since lost to various debtors.

A Mulciber-forged artefact was a badge to be worn, a trophy to be displayed. A sign of judgement and approval, more so than a list made by a crabbity old man.

Post link

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient House of Lestrange

Four heirlooms of the Strangers; powerful warlocks the muggle Gauls called sons of Toutatis. A death coin for enemies, a torc for luck, a sword for immunity and a dragon’s infinity knot.

There is little that the two branches of the Lestrange family agree upon - the longstanding disagreement between the French and the English line stems from a feud in the early 11th century which was never resolved satisfactorily. In fact, the only thing they do agree upon is their divinity. The Lestranges, unlike most venerable wizarding families, trace their descent to a wandering family of warlocks in Iron Age France whom the Gaulish tribes came to worship as protectors of the tribes and in time, war gods. (The other thing both lines of the Lestranges agreed upon was that blood was awfully nice and one could never have too much bloodshed.)

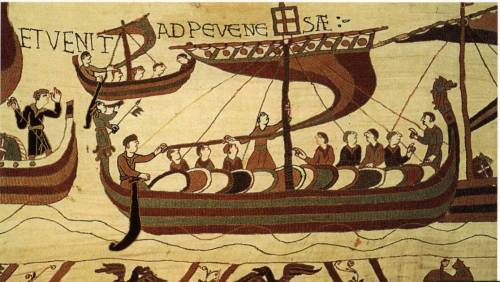

The feud between the two branches is a complex matter. It began in 1066 A.D. when the Lestrange patriarch died, leaving behind two sons and a tidy amount of gold, lands and peasants to be divided between them. His will was never found (destroyed, claimed each of the sundered lines of the Lestrange family) and the two were left to divide his wealth between them as they saw fit. It is here, in their telling of their history, that the stories of the English and the French Lestranges diverge and each side claims theirs was the truest, they were the most wronged.

The French Lestranges tell a story of greed and avarice. The younger, ambitious and hungry for a life far beyond his means, demanded he be given the lion’s share for he had plans that his elder brother lacked. His elder brother refused, quite rightly, but the younger was not content to let the matter lie. The younger Lestrange rallied a motley army of serfs,household knights and mercenaries to wage reckless war upon his elder brother. This proved to be his undoing for his brother held the stronger claim to the lands and wealth and the greater part of the family’s forces rallied to him. Thwarted, humiliated and bankrupted, the younger Lestrange - they claim - fled with his family on William’s ships to England with several priceless family heirlooms (stolen, not their own, ought to be returned), to escape the hand of justice which truly ought to have been their inheritance.

The English Lestranges tell a very different story altogether. In their tale, the elder Lestrange promised his brother the share of money their father would have wanted him to have. But when the time came to divide the wealth, the elder son turned his back on his brother and declared that this father would have never left the younger the share he demanded as his birthright - yea, would not have left his younger son any money at all if not for the tenderness of his heart. Greedy, the elder called him, irresponsible, frivolous, and so speaking, cast his brother out with nothing to his name.

Thus cheated of his inheritance, the English Lestranges claim the younger brother did what he could and attempted to rally the Lestrange fiefdom to his cause - failing only because they were niggardly cowards who lingered, tending their fields instead of fighting for him. Penniless and pursued by muggle bloodsuckers he fled with his family and came to England on William’s ships, with nothing but their clothes and some heirlooms which were theirs (not stolen, their own, made for them, owned by them). For their loyalty to William of Normandy and their prowess on the battlefield at Hastings, they were well rewarded and given a fiefdom of their own. This marked the beginning of the English line of the Lestranges.

The truth was such a complicated matter. Those who had looked into the matter, family biographers and the like, had ended up throwing their arms into the air in despair and given up - until finally they chose their sides by their proximity to each branch of the family. Those in France declared the French Lestranges wronged - the English dogs had stolen from them, ought to return the priceless goods stolen from them. In England, however, they sang a different tune: the frogs were penurious swindlers who had come by their just deserts when their brother had left, taking their most precious, most valued treasures, claiming it as his inheritance. Miserly swindlers who would cheat their brothers deserved as much.

As for the truth? Truth was cast to the wind - who knew what the actual truth was? History was, after all, nothing more than a set of lies those with power agreed upon.

Post link

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient House of Black

Three sisters: Morgana, Morgause and Elaine of Garlot. One dark, one brown, one fair. Three sisters: Bellatrix, Andromeda and Narcissa. One a warrior, one a rebel, one entirely unexceptional.

Of all the houses of the Sacred Twenty-Eight, the Blacks were the only ones who could trace their descent to an ancient royal family, canonized in both myth and legend. There were those who were openly skeptical that a wizarding family could claim to be related to Arthur, King of the Britons and his three half-sisters; Morgana, Morgause and Elaine of Garlot - such a claim, they said, was far too exaggerated and could never be proven (for none were allowed to see the Black family tapestry but the Blacks themselves). But most agreed - out of fear and awe - that the Blacks indeed were children of these great sorcerers.

For how could they dispute it when all the portraits of these mythical figures seemed to live again in the faces of the Blacks striding alongside them in the Ministry, studying at Hogwarts, holidaying with them in the South of France?

But if those concerned with the veracity of this outrageous claim had bothered to dig through records held in the Department of Mysteries - held purely for historical purposes, of course - they might have found a series of bills and commissions to various unknown artists and artisans of the early 11th century. Of early tapestry-weavers instructed to portray their patrons as characters from Arthurian legends - else face death (how wonderful those ancient times were, where the missing poor prompted no visits from the Auror department). Of mosaics and etchings presented to this family; all the children of the Lady Igraine shown with the high cheekbones, dark hair and pale faces particular to the Blacks. Of portraits and paintings and landscapes - all in the grand tradition of the rich families of those times. In time, any traces of the original Arthur and his half-sisters were lost and all the artworks concerning the Arthurian legends - even among the muggles - came to assign each character the same face over and over again; pale skin, dark hair (sometimes light for Elaine of Garlot was a fair young maiden), high cheekbones: trademark of the Black family.

And yet these records would mean nothing, not even in a history textbook, not after all this time. For who could say, after all these centuries, that the Blacks were not descended from Arthur, Morgana, Morgause and Elaine?

The Blacks were not practically royalty. They were royalty.

[Paintings: Morgan le Fay by Frederick Sandys, The Magic Circle by John William Waterhouse, The Accolade by Edmund Blair Leighton

Photo Credit: Helena Bonham Carter as Morgan Le Fay (Merlin, 1998), Katie McGrath as Morgana (Merlin, 2008), Imogen Poots as Fanny Knight (Miss Austen Regrets, 2007)]

Post link

Amar baccha! My children, listen, for I have a story to share with you.

In the beginning there was the Kund, the deep wellspring from where the first Ohm of the Universe flowed. Soon other sounds and utterances flowed through, forming brooks of syllables, joined into streams of words, joined into rivers of sentences, joined into seas of stories, joined into oceans of truth.

And each sound and syllable and word, each sentence and story and truth, each little drop carried with it the Power of Creation and Destruction, the Power of Language: together like the ebbs and flows of tidal waves, like drought and floods, like sunshine and rain.

Creation comes from Destruction comes from Creation.

And this Power, the Power of Language, this exists for all those who speak, listen, write, read. For all those that carry Language in their heads and in their hearts. For it is Language that is your birthright and it is Language that is your responsibility.

And Language is not to be restricted, to be hoarded as though it is some precious and rare gold or silver. No, Language is to be shared by all, for it is everyone’s birthright, and everyone’s responsibility, to partake in the ebbs and flows of Creation and Destruction.

You are not the Master of Language, much like you are not the Master of Water or Air. You, all of you, are in Service to Language, much like you are in Service to Water or Air - Powers that create you, Powers that sustain you, Powers that destroy you.

There are some of you that will be entrusted to ensure the safety, sanctity, sanctuary of Language. You will be known as the Compassionate Ones, the Shafiqs, caretakers and custodians of Language and all those that wield it. It is your responsibility to care for the hearts and heads of those you serve, to ensure that their needs and desires are met, that they remain safe and protected and well. It is your responsibility to ensure that Language is shared freely, that Language is served for the greater good, that all hold access to Language and that your Language does not die before it is time.

And oh how its time will threaten to come! For there will be forces that claim to be Masters of Earth and Fire, claim their right to ravage your lands and control your people with ever-changing boundaries and restrictions. Forces that claim to be Masters of Water and Air and destroy all which you build in symbiosis to create that which dominates. Forces that claim to be Masters of Language, their own Language, while denigrating yours as lesser-than, impure, powerless.

And then there will be forces of your own. You claiming responsibility as privilege and using your custodianship as cruelty. You forgetting your own birthright and believing those that say your power can only be accessed by a select few through specific means foreign to you. You letting go of your Language, that which gives you Life, and forgetting all the syllables and stories and truths that it carries.

Destruction comes from Creation comes from Destruction.

The Power will still manifest, still create and destroy, even without your wielding of Language, even without those who speak and listen and write and read. It is Power that has existed before there was Humanity and will exist after there is Humanity, for it is Power that has created the Universe and will destroy the Universe.

Learn to approach Language with respect and responsibility, and you will gain strength, fortitude, prosperity, livelihood. But treat Language as though it is something you can control, restrict, deny, destroy, and you will find that it will control, restrict, deny, and destroy you.

And if you ever find that you are close to the brink of no return, return to the Waters: the oceans, the seas, the rivers, the streams, the brooks. Return to the wellspring, to the Kund, and call out for a new Ohm.

Remember this, baccha, for forgetting is the first step to Destruction without Creation.

[[source:Belinda Meggit

So thepostmodernpottercompendium is hosting this really interesting series on the origins of magic which is now becoming an interesting story in progress. I have been meaning to write this story for a long time, ever since I found this picture in researching the bede, or gypsy boat people of Bangladesh:she’s one of them. I knew she was the face of thedainee that mysteriously guides the Bideshis as soon as I saw her picture, and now I want to write her story.

The line about the kund and the first ohm is from a piece by Minal Hajratwala, about being a kinky queer femme Indian woman. In the piece she plays a lot with language and draws the connection between “cunt” and “kund” - as in “kundalini”. The name of the piece escapes me right now but it was performed in this year’s Yoni Ki Baat in SF.]]

Post link

[[so ever since Shafiq appeared in the Sacred Twenty-Eight list on Pottermore it’s become a growingly-popular last name in fanfic, but there are some uses of Shafiq that kind of make me wince, even if unfairly.

The most jarring ones are the names where Shafiq is paired with a very bog-standard Anglo name - say Bob Shafiq or Jane Shafiq. Because the Potterverse isn’t white-washed enough as it is? I often have to check myself when I see this happen because my own name is an English word (Tiara) and there are Anglo names that travel (Daniel, Sara), but even within my family tree that’s fairly unusual.

The other extreme of this is picking very Arabic names and setting the characters as being from the Middle East. Yes, Shafiq is from Arab origin, but names travel! It’s a common-ish Muslim name, and Islam has a lot of roots outside the Middle East - hell there are a lot more Muslims in Asia than Arabia. A lot of Africa is Muslim, Bosnia and surrounding Central Asia/Eastern Europe esque countries are Muslim, and there’s all the converts and enclaves and intermarriages etc etc etc.

I’ve seen Bangladeshi Shafiqs and Malay Shafiqs (as well as variations on the spelling, such as Shafik and Syafiq) and I’m sure that there are Shafiqs of all sorts of ethnicities. I would love to see a lot more diversity not just in the naming, but also in the origin stories of these characters. How about, say, a Ali Shafiq, Malay wizard from Singapore? Or a Siti Nurain Shafiq from Jakarta? Or an Afroz Shafiq from the East Indian diaspora based in Kenya? Or or or…

So many possibilities for names, let’s look outside the bog standard!]]

thepostmodernpottercompendium:

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Shafiq and Shacklebolt (2/?)

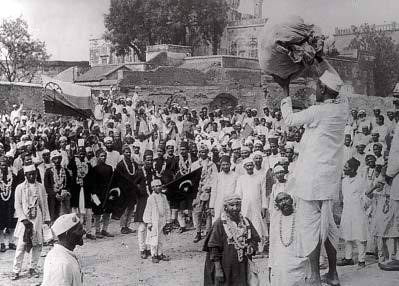

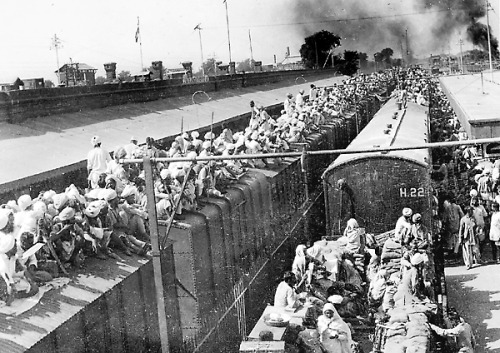

Pictures, left to right: Jallianwala Bagh Massacre 1919, Non Cooperation Movement 1920-21, Dandi Salt March 1930, Bengal Famine 1943, Trains during the Partition 1947, Indhira Gandhi visits Bangladeshi refugee camps in Bengal 1971.

He does not understand, when he is five, why his mother is weeping for people in a far away place with a strange name which is not home.

When he asks her, she only cries harder, and his father grips him roughly by his shoulder and pushes him away, admonishing him for troubling his mother. Someday, his father says, you will understand.

(He does not tell them, after asking his ayah, that he still does not understand why they care about wicked people who think they can get away with murdering innocent people. Why should they care? They are not theirpeople.)

He does not understand, two years later, when they return from the Halloween ball at the Ministry of Magic; the wrath of Kaliherself writ large upon his mother’s countenance (though she has long since given up her old family gods) and his father’s eyes shining with the same light of battle which must have once shone in their forefathers’ eyes as they swept out of the Hindu Khush following Muhammad of Gor.

Shafiqs are landowners and caretakers, yes, says his father, we grow and we create and we heal the land, but there is also anger in our hearts and when the time comes, we are warriors as well and all men quake when a Shafiq raises his arms to go to war.

(He tells his father he is not a Shafiq then, because there is no anger in his heart and his father only laughs and ruffles his hair and tells him that when he is older, the anger will burn in his heart too.

It is the last time, for a very long time, he hears his father laugh so openly.)

He does not understand, nearly twenty years later, why his mother both laughs and cries at the letter his father sends them from the old country, complaining about the damn bilatisthinking they’re clever by refusing to put us in prison. This is no laughing matter, being put in prison. It is wrongto break the law.

His mother silently hands him a book by a man called Olaudah Equiano and tells him that sometimes men make bad laws and it is for them, the ones who take care of their people, to fight those laws.

(He begins to understand, a few years later, when he realizes that his colleagues at the Ministry care more about Grindelwald’s war and its ill effects on England, not the millions starving back home, or the boats burning to keep the Germans (or the Japanese) from freeing his people; when they talk of oppression by mugglesand he wonders what the non magical folk have ever done to them that can be compared to what they have done to his people - then he understands, they do not look beyond their navels, so they exaggerate their pain, these pampered dandies.)

He does not understand why his father is grim-faced and his mother cries and cries and cries when Clement Attlee finally gives their countries Independence and the bilatisleave. It is a time for celebration - they have finally won their war. People die all the time. Let them die; they are not their own, they are mugglesthey do not have magic.

His mother goes into hysterics when he says this and his father fixes him with such a stare, he nearly wets himself.

Are you a Shafiq? His father asks him, are you my son or a son of a pig? A fool that you spew such nonsense? Are you blind? Have the bilatis turned your brain to porridge?

(He understands, a little, when as he watches his mother’s body burn on the funeral pyre, the tears begin to flow. Death is not easy to see. His father gruffly tells him to be a man and stalks away. Proud and tall as always.)

He begins to understand even more, when he meets his Anglo-Indian wife’s family and he listens to them drawling away about how the homeland is dirtyandstinky and his people are backward.They are your people, your forefathers he wants to yell, but smiles apologetically as his wife squeezes his hand sympathetically underneath the table.

He understands better, when he reads Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835) and he reads these words:

We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.

He finally understands properly, twenty three years later, why his mother wept when their people, once united by common cause against their oppressors, turn on each other and commit genocide over divisions created by those very same oppressors they fought to drive away. He understands, when not a murmur is heard in the Ministry of help to be sent to them - when British newspapers are silent about sending troops to help clear up the mess they made in the first place.

But by then it is too late to teach his son what it means to be a Shafiq; to be rich and yet have anger burn in your heart.

So he teaches his grandson instead. These are only stories to them both, but he sees the fire of anger in his grandson’s eyes when he teaches him the history they do not teach them at Hogwarts. Of how the men of this country went to their homeland and stole from them in the greatest sanctioned robbery in the history of the world - 2.5 billion pounds (probably a lot more) stolen to never be returned. Of how, for two hundred years, they were taught that their ways were inferior and foolish, based on superstition not science. Of how they burnt their boats and stole the very souls and identities of people by turning them British, by turning them against their own culture (like your father, he says regretfully).

Of how these very men turned their people against each other: one religion against each other, countries arbitrarily divided along the lines of religion leading to one of the largest massacres in history. Of how ten million of their people were displaced overnight, in a war caused by the same arbitrary division of nations along the line of religion and politicking - this time for culture and language, because truly what did people in Dhaka have in common with people in Islamabad besides a vague commonality the bilatisdecided superceded all other commonalities? But now ten million people fit neither here nor there - they were not Bengali because they were muslims but they were not Pakistanis either (how could they be, those northeners were so different.) Ten million people with no identity, always to live unsure of themselves. This was the story of their people; magical or not, allof them were theirs.

And then many years later, his eyes are misty with tears as he watches his seventeen year old great grandson snap his wand and declare that he will not live as a bilatiwizard among a people with no conscience and no guilt for their cruelty. He goes to muggleuniversity instead, and then returns to his homeland to make a difference by working in a muggleNGO, practicing their old magic. The magic of their forefathers. And nobody serves him notice for using magic in the presence of muggles.

It is a start, he supposes, and then imagines his father would be proud. The anger has burnt in his heart and he has passed the flame of anger on. They will be caretakers, they will be warriors.

There will always be a Shafiq as long as they remember.

[Pic sources will be added later. Many thanks to notyourexrotic for helping with various bits of information and shaping this story (also for their incredible project shafiq28 which, I’ll be honest, shaped the headcanons for this one in a hugeway). I never liked the whole Statute of Secrecy biz given its ramifications when you apply them to other countries outside of the Euramerican region - its similarities with the whole divide and rule policy which governed Brit colonial policies when they were leaving countries are far too close for comfort.]

[[re-reblogging for this as there’s been an update to the original.]]

Post link

[[entire discussion OOC]]

the thing that fucks me up most with harry potter headcanon as a mixed chicana w/ native+”mestiza” roots is that “purebloods” already wiped us the fuck out. you can play harry potter and pureblood as a metaphor for british classism all you want but don’t tell me that the Salem Witches academy wasn’t built on the site of native americans lands, don’t tell me that european wizards and witches didn’t come to the americas and slaughter those who weren’t secretive about their magic, who didn’t have muggles, don’t tell me they didn’t slaughter us/the american magical peoples, they didn’t convert as many of our ancestors to god-fearing religions as possible because then our brothers and sisters would fear the witches and force magic back into secrecy and out of the hands of our kings and queens, our chiefs, our sages, shamans, healers, don’t tell me that spanish and british and french wizards didn’t come to the americas and round us up, ripping the magic users away from their families to be schooled in proper wand-using magics instead of wandless or wordless or magic by other means in boarding schools which humiliated us, which stole our native tongues and obliterated our heritage and our native power and then mocked us for when we continued to strive to fit our own cultures into their tiny tiny molds

don’t tell me that abuelas and abuelos don’t whisper to their grandchildren the old spells they still know, that in secret, we still cling to magic that they could never understand

voldemort as a singular villain isn’t so scary when your people were raped, enslaved, and slaughtered across two continents for hundreds of years

imagine the bitter laughter of the elderly curandera — ay, now they’re worried about who is being killed

imagine the blood your headcanon is built upon

This is where I’m going with my Shafiq Twenty-Eight series, though it’s kind of a class divide on multiple angles. On the one hand, you have the general population of Bidesh (magical Bengal/Bangladesh area) who think the Bilatis (Brits) are stupid for trying to impose some sort of separation between magical and muggle and thinking that magic is so clearcut.

But on the other hand, you have the upper-class Shafiqs (who in my fic are more like feudal landlord types that may be loosely related to each other) who subtly look down on the commoners and disregard them as farmers or pheasants (though that’s not all the common folk do). I don’t think their disdain is malicious per se - ignorant condescending benevolence, perhaps. They didn’t get around to building a school and codified magical system until relatively recently, and most of that is because they notice that the commoners are itching for a revolt and the school is their means to quell the masses (especially if they offer scholarships to the high-achieving poor kids, like Ayesha’s mother Sabila).

The heart of jadu in Bidesh is in their culture and literature and language, which permeates the country and is the main reason for Bangladesh’s liberation and existence (hence the problematic nature of trying to impose the Statute on them). However, a lot of the practical skills of jadu,knowing how to harness that culture and language into magic, comes from the bede, the boat people, the villagers. They haven’t forgotten.

And in some way the Shafiqs, like Begum Indrajala, know this. Their job as a Shafiq is actually to be a trustee to this magical knowledge, to ensure that the culture stays intact and the heart still keeps beating. But somewhere along the way they got power-hungry, they got patronizing, they though protecting their people meant treating them as little children. They chased glory and forgot greatness.

Even as they fight off the British and Pakistani colonialists (magical or otherwise) for trying to suppress their culture, they are doing damage to themselves.

I was just on the phone with my mum, who didn’t quite get what I was trying to explore with the class divides in my story. She thought that Sabila being a bedewas nonsensical - surely she’s a lot more sophisticated than that (well, it was mostly because Sabila is inspired by my mum somewhat and she thought I was calling her uneducated). She also questioned my use of casi for the commoners because that’s what you call really backwards village uneducated folk. But that’s kind of the point - they’re actually the most educated out of everyone, but the Shafiqs in power don’t really respect that because the commoner education doesn’t look like the Shafiq education - it doesn’t look like their private tutors, it doesn’t look like Hogwarts or Durmstrang, it doesn’t look like the Cadet College. You want to be seen as worthy? Follow the structure. None of this loosey goosey business.

I’m also trying to figure out how this fits with the Trixie/1920s Bengali Harlem storyline. Her mother is from Louisiana Voodoo stock, so she would have learnt a lot of old magic that way, and her dad is a Shafiq, but pre-Cadet College. I’m thinking of how in Malaysia you’d have a lot of people that have hereditary title-names like Raja or Puteri or Syed and usually that hints to some royal lineage but they’re so far removed that functionally they’re like regular folk. Considering the way family trees work in Bangladesh I figure that Trixie’s dad is more of a distant relative than a direct descendent, having some cousin or other study at The Big Magic Schools, relatively middle-class by Bangladeshi standards - I mean, he’s an international merchant, he has a fair amount of money, but he hasn’t completely forsaken his roots.

I know stopdropandbeauty was planning on exploring issues of colonization and imperialism and native genocide in potential HP headcanon/fic, and I feel like some of the other headcanon blogs have touched on that one way or another. HP Headcanon Tumblrs seem to be a trend now, so maybe someone will pipe up and write something along those lines!

(also I wonder if part of the original meta is running under the assumption that only White people can be from Pureblood families, at least in JKR’s stated canon. I pounced on Shafiq when I saw it in the Sacred 28 list because that’s my last name, it’s a name rooted in a rich cultural history that is not White European, it’s real. The only other real-sounding last name on there is Abbott though I couldn’t be wrong. And there’s also Shacklebolt, and the one canon character we meet from that line is Black.)

My family were always very adamant about getting the best education possible. It was a conviction that went for generations, not just limited to Shafiqs or even jadukara: it permeated across Bengal, crossing through the Subcontinent, spreading through most of Asia. Education was the key to everything - livelihood, freedom, power, success. And for my family, only the best would do.

They did wish they could send me to the Cadet College where they met, but after the Liberation War there were just not enough resources left to bring it back to even just pure functionality, let alone its former glory. My parents left Bidesh, left Bangladesh, to find better futures - especially for me, their only child.

So I am well aware that I sound like a petulant, ungrateful child when I say that being in Hogwarts was very rough and difficult for me.

I arrived in Hogwarts a year or two after the Second Wizarding War, where Lord Voldemort was defeated in the Great Hall, causing the school to take a short hiatus to rebuild. I was both a little too young, and a little too transient, to really know much about the Bilati war. My parents had moved to England not too long before I was born and had mostly kept to Muggle society, since you were more likely to find other Bengalis there - even a few jadukara. They left to avoid the worst of the war - trying to get involved in another one would be folly.

When I arrived at Hogwarts - via an acceptance letter that my parents were both highly surprised and very elated to receive, since they were well aware of Hogwarts’ prestige but didn’t think immigrants were eligible - a lot of students had bonded over their shared experience of the war. Many had lost family or friends to it; a few had been in the frontline. I thought I might have something to contribute too - my family just went through a war themselves, my entire culture was at risk, I too am a war survivor. (Sort of. Maybe.)

But that didn’t seem like enough. Their war was sequestered away from the Muggle world; if you weren’t a wizard, you wouldn’t understand. My war made no magical distinction, but upheld a rich cultural heritage that underpinned our magical ability - a heritage alien to their world.

I didn’t quite know what to make of the Hogwarts letter. My family had talked about it, had talked to me about jadu and some of their experiences, but they mostly wanted me to adjust to regular British life. Sometimes I heard them grumble about how they weren’t as free to practice jadu as much as they wanted to because of the Statute, how they figured that their knowledge was probably banned in Bilat anyway (they did ban flying carpets, after all), how if there was no Operation Searchlight, no war, no suppression we could have had a very luxurious bountiful life of being a jadukaranoble.

Perhaps they felt that me being at Hogwarts meant that I could get the time and space for magic that they missed. I wouldn’t be bound by statutes or restrictions. I could really dive into my birthright. I could revive the name of Shafiq, return what had been forcibly taken from us by bands of colonizers.

All that ambition and desire for greatness was likely what got me sorted in Slytherin. There were a few others in my house that had descended from families of much renown, families who also treasured prestige and power. Like me, they were sent to Hogwarts with big expectations - to rebuild names that had been torn apart by battle.

But we were only eleven, twelve, thirteen. Not even puberty yet for some people. What would we know about power and prestige? We just wanted to play.

My house seemed to have a harder time at Hogwarts than most others. People talked about unearned bad reputations, about everyone else assuming that we must have been on Voldemort’s side, about how we can’t trust the other houses just yet, just because you don’t know how they’d regard you. The only ones you could trust were your fellow Slytherins: we took care of our own.

Except I’m not sure that quite happened for me. I wasn’t ostracised or bullied, oh no. I did manage to make some friends, and a lot of the classes were…not easy necessarily, but not agonizingly hard either. (History of Magic and Muggle Studies were the main ones that gave me headaches, only because they were both so restricted in subject matter and some of their facts were dubious. Not every magical culture uses a wand, for Gods’ sake.)

But I think when you’re entering a world that is already so abstract to you in multiple ways, when you’re somehow supposed to be part of the secret In-Crowd yet you feel like you’re only qualified enough to be the Outsider, when you’re having to navigate multiple new cultures at once…that gets tiring after a while.

I couldn’t trade war stories: I wasn’t there, no one I knew was there, we were all fighting a different war. I couldn’t talk about learning magic from a kindly elder as a child: the only elders I had were my parents and the odd uncle or two, but the very limited amount of magic they exposed me to wasn’t even the same sort my classmates learnt. I couldn’t talk about what my family did over the holidays - we had a completely different set of holidays to work with, and the extent of my participation with Christmas was to visit some friends of my family’s for dinner.

I generally got along better with the Muggle-borns; they too were grappling with culture shock, not quite knowing if they’re allowed to claim themselves as witches or wizards, not when the effects of the Muggle-Born Registries were still fresh. There were a few Muggle-borns that had arrived later to Hogwarts than usual because the War-time Ministry did not allow the school owls to let them know they were eligible to study, and they had to play catch-up a lot, possibly for the entirety of their school years. Always a little bit behind, never quite getting it, objectively skilled and competent but still struggling culturally.

And even then it was a little tricky, because they were British, always had been. Technically so was I: British culture was the best culture I knew, more than Bengali culture or any other culture my parents would have known. But it’s such a different experience of Britishness when you had kids stab you with ‘paki’, when people keep asking you to repeat yourself because 'your accent got in the way’, when no one quite believes you when you say you were born at the hospital down the road and instead insist that you were born in the Ganges River.

To Hogwarts’ credit, I didn’t get as much of the racist backlash here. But I still had to deal with the clueless questions, the people thinking my last name is Patil, the attempts to fix my accent in Charms class.

Maybe I’m just oversensitive. I don’t know. The whole school was recovering from major trauma. They don’t have time to deal with one student’s identity issues - not when the school had an identity crisis of its own. Especially Slytherin House: who were they, without the blood supremacist stigma, without the easy stereotyping of alliance? How do you maintain your own core being when everyone and everything else parses you by your supposed history? Who can you trust to be just youaround?

I don’t know if I am destined for greatness, power, prestige. I’m not sure the rest of my house, or my school, quite knew that either.

[[source:kawaii palace on flickr - her friend theladyvon makes the robes in the picture for AUD$60 plus s&h.

this piece was long delayed because I could not obtain any Slytherin art with someone vaguely resembling Ayesha in it. and my comp’s too old to really do graphics editing. sorry!]]

Post link

“Sabilabeta, please - please come to your senses!”

Mahmubah watched her daughter storm off in a huff, refusing to look back at her. Was this really her daughter? The one who thought her family was the universe, who would giggle as her mother and aunties braided her everlong hair, who would listen intently to stories of the dainee and annoyed her older cousins by being the favourite student of their jadukara elder (“she’s not even supposed to be here!”) and dreamed of mastering the difficult and arcane mysteries that were shopnojyoti?

Would her daughter really dare be so biadab to her elders, so stubborn and petulant? Well, Sabila was always stubborn, but normally she was stubborn for a good reason - like wanting to learn more and more, or wanting to help with the fishing and cooking.

But wanting to run off and marry a Shafiq?That was not a good reason.

“Maa! I have come to my senses! He is a good man, and we will have a good life. You can have a good life too, can’t you see?”

“A GOOD LIFE?! Is your life not good enough already, being with your family, living a simple village life?”

No, that goddamned Indrajala Cadet College corrupted her, taught her that her people’s ways were faltu and messy and old-fashioned, taught her that the only good way to do jadu was to be like the Bilatis: quick fixes and short sentences.

Taught her that the only good jadukara were the Shafiqs, because they owned land, and her people deserved to be ruled over because they were transient and spent more time in the rivers.

Casi, those Shafiqs called them. Peasant. Country bumpkin. Gravel and poison in their mouths.

Sabila looked back at her mother, not quite knowing which age to be: her body feeling out twenty, her mind fresh out of school and primed for a new adventure, her eyes with the same earnest twinkling from infanthood. Did her mother want her to be an independent adult or did she still see her as the child with the braids?

“Look, Maa! We live hand to mouth, hoping Allah will bless us with fish and rice, having to move around all the time because the cyclones and floods take everything away! Not even the strongest jadu of our kind can conquer Mother Nature! We are being destroyed, Maa - but this is our chance to survive.”

“IT IS THAT MAN’S FAMILY THAT IS DESTROYING US!” If Mahmubah was not too tired she would have slapped Sabila. “They pulled us from the rivers, our soul and blood, and made us come to land. They took away our connection to the water - that is why the cyclones and floods wash everything away. They have stopped paying respect to the water; instead they seek dominionandcontrol, as though they are Gods. As though they are the dainee! They and their Godforsaken school, wanting to control jadu, no respect for where it came from - the WATER!”

“You sent me to that school!” yelled Sabila. When she was not even ten, a couple of staff members from the relatively-new Begum Indrajala Jadukara Cadet College had visited their bank of the river to look for students. They were impressed enough by Sabila’s talents and sheer enthusiasm to offer her a full scholarship.

Sabila thrived in that school: her love of learning flourished as she was exposed to a wealth of subjects and skills, most of which she would never have imagined back in the river. She picked up TantramantraandAyurveda with ease, having had a lot of practice back home and relished the jadunai subjects like Mathematics and Art and English since they were so newandfresh to her.

(To her puzzlement the subject of shopnojyoti was barely mentioned anywhere in her studies - if it did it was only referenced as a lost, possibly mythical art. Sabila did spend some time trying to investigate what her teachers really knew about shopnojyoti, but after one too many deadends she dropped this line of inquiry and focused on regular schoolwork.)

Her absolute favourite school subject was Sahitya, Literature - a curious blend of jaduandjadunai. The works and writers she studied had achieved acclaim amongst the jadunai, even outside Bidesh, winning awards with strange names like No-Bell. Yet these works were so clearly written by jadukara, so infused were they with magic and power - the heart of jadu beating through the mastery of the Bengali language.

It was through Sahitya that Sabila lost her heart: to Faizal, a young man maybe a year or two older than her, as energetic and macho and boisterous as any other male his age - except he was a Shafiq. One of the Zamindars, the landowners. Probably a heir to the school. He wasn’t as passionate about learning as Sabila, indeed even with his family status he didn’t stand out much, but he was funny and had big ambitions and treated Sabila like a queen. Faizal watched Sabila recite some Chakravarti poetry at a joint recital, one of the few times the boys’ and girls’ sections came together, and fell in love with her beauty and depth of passion.

Their depth of passion sparked a love affair that had to be kept relatively secret during their school years - can’t destroy your dignityandhonour, you know - but after years of passing poetry back and forth and cheering on sports games and late-night walks with mishti and moonlight, Faizal proposed marriage.

“You are my sultana,” he said. “Let me give you the good life, be part of the Shafiqs, never a care or worry in the world. Be a real sultana.”

Sabila had been surrounded by Shafiqs - most of the school consisted of them or their peers, landowner families with privilege. There was even the odd Bilati or two, the occasional Cinadeshi and Japani, and a few who were like her - poor river people on scholarships. The Shafiq students didn’t talk to her much, but Sabila admired them all the same: their grace, dignity, ease with power. Their elegance and beauty. Their chatter about those strange exotic cities they would go to on holiday - London and New York, Alexandria and Istanbul. They had everything they ever wanted. They never needed to struggle.

Sabila remembered years of barely being able to eat when cyclones and floods would wreck their makeshift towns (a fairly common occurrence). She remembered the clothes getting threadbare, there was only so much that repair spells could do. She remembered late nights staring out onto the rivers, wondering why their boats would never travel further into the oceans, is that not what boats were for?

What was her life for, if not to explore with elegance and grow with grace? How could her mother not see how much better her life would be married to a Shafiq? Did her mother notwant her to have a good life?

“We sent you to school because we wanted you to have a chance at a good life.” Thought so! Just as Sabila was about to jump in:

“Butbeta, being a Shafiq? They are different from us. They don’t respect us. They are of the land; we are of the water. Let those of the land return to the land, and those of the water return to the water.”

“Didn’t you say all jadukara come from the water? That includes the Shafiqs. That includes Faizal.”

“THE SHAFIQS HAVE BETRAYED THE WATER! They have forgotten about the ways of the water! Did you not listen to me, baccha?! They turned their backs on the water to rule the land! They turned their backs on us, on you!”

“I AM NOT A BACCHA!”

Sabila was furious. Her mother saw her not just as a child, but a baby. Who was she to preach about respect when she wouldn’t respect her own daughter?

“Faizal did not choose to be a Shafiq,” said Sabila after a (slightly futile) attempt to calm down. “But he chose me. He could have chosen anybody, even another Shafiq or a Bilati girl, but he chose me. He wants me to be his sultana, Maa. He wants me to have the good life.”

“Does he want us to have the good life?” asked Mahmubah, losing patience with her daughter’s insolence. “You don’t just marry one person, you marry into their family, their community. Is he going to provide for us, or is he just going to rule over us and make us suffer so that we can provide for your sultanalife?”

“He will not make you suffer - I will not let him make you suffer.” Sabila was losing patience with her mother’s obstinance. “Please, Maa. Faizal is a good man. Just at least meet him. I promise, he’s not like all the other Shafiqs who don’t care. He cares. He cares about me and he will care about you.”

Sabila sat by her mother’s feet. She knew her mother had reason to doubt; she did lose her father, after all, to mysterious circumstances that left her mother barely able to take care of her even with support from extended family. But Faizal was different. She’s sure of it. If only her mother would give her a chance…

“Okay. I will meet him. But I cannot promise that I will approve. I need to make sure he is good enough for my daughter.”

Sabila kissed her mother’s feet in gratitude. Believe me, Maa - we will not let you down.

[[picture sources: articles on demotix (1,2) and sfgate about the Bede people-nomadic river-gypsies of Bangladesh that practice magic. (I’m aware that the term “gypsy” is a slur against Romani people; however, almost all my sources about the Bede people (inc from Bangladesh) use “river-gypsy” as a descriptor and I’m not sure what other terms are favoured by that community since they’re not English-speaking.

My computer can’t really deal with most graphics software and the originals of the demotic photos are about 55GBP each, so please excuse the massive watermark.

Sabila is the name of the woman whose photo I used to talk about a Bangladeshi magic wedding. Mahmubah and Faizal are named after my parents.]]

Post link