#seed dispersal

When Acorn Masts, Rodents, and Lyme Disease Collide

When Acorn Masts, Rodents, and Lyme Disease Collide

“‘Mast years’ is an old term used to describe years when beeches and oaks set seed. In these years of plenty, wild boar can triple their birth rate because they find enough to eat in the forestes over the winter… The year following a mast year, wild boar numbers usually crash because the beeches and oaks are taking a time-out and the forest floor is bare once again.” — The Hidden Life of Trees by…

The Weeds in Your Bird Seed

The Weeds in Your Bird Seed

With February comes the return of the Great Backyard Bird Count, a weekend-long, worldwide, bird counting event that Sierra and I have enjoyed participating in for the past few years. While you can choose to count birds anywhere birds are found, part of the appeal of the event is that it can be done from the comfort of one’s own home simply by watching for birds to appear right outside the…

Winter Trees and Shrubs: Northern Catalpa

Winter Trees and Shrubs: Northern Catalpa

The names of plants often contain clues that can either help with identification or that tell something about the plant’s history or use. The name, catalpa, is said to be derived from the Muscogee word, katałpa, meaning “winged head,” presumably referring to the tree’s winged seeds. Or maybe, as one writer speculates, it refers to the large, heart-shaped, floppy leaves that can make it look like…

Seed Shattering Lost: The Story of Foxtail Millet

For a plant to disperse its seeds, it must first let go of them. Sounds obvious, but it is a key step in the dispersal process and an act that is actually coded in a plant’s DNA. As fruits ripen and seeds mature, an abscission layer is formed that separates the seed-bearing fruits from the plant. No longer attached to their parents, seeds are left to their own devices. If all goes well, they will…

Violas keep a secret hidden below their foliage. Sometimes they even bury it shallowly in the soil near their roots. I suppose it’s not a secret really, just something out of sight. There isn’t a reason to show it off, after all. Showy flowers are showy for the sole purpose of attracting pollinators. If pollinators are unnecessary, there is no reason for showy flowers, or to even show your…

Dispersal by Open Sesame!

Dispersal by Open Sesame!

In certain instances, “open sesame” might be something you exclaim to magically open the door to a cave full of treasure, but for the sesame plant, open sesame is a way of life. In sesame’s case, seeds are the treasure, which are kept inside a four-chambered capsule. In order for the next generation of plants to have a chance at life, the seeds must be set free. Sesame’s story is similar to the…

Burr Tongue, or The Weed That Choked the Dog

Burr Tongue, or The Weed That Choked the Dog

It is said that the inspiration for Velcro came when Swiss inventor, George de Mestral, was removing the burrs of burdock from his dog’s coat, an experience we had with Kōura just days after adopting her. I knew that common burdock was found on our property, and I had made a point to remove all the plants that I could easily get to. However, during Kōura’s thorough exploration of our yard, she…

The Serotinous Cones of Lodgepole Pine

The Serotinous Cones of Lodgepole Pine

Behind the scales of a pine cone lie the seeds that promise future generations of pine trees. Even though the seeds are not housed within fruits as they are in angiosperms (i.e. flowering plants), the tough scales of pine cones help protect the developing seeds and keep them secure until the time comes for dispersal. In some species, scales open on their own as the cone matures, at which point…

Book Review: In Defense of Plants

Book Review: In Defense of Plants

Many of us who are plant obsessed didn’t connect with plants right away. It took time. There was a journey we had to go on that would ultimately bring us to the point where plants are now the main thing we think about. After all, plants aren’t the easiest things to relate to. Not immediately anyway. Some of us have to work up to it. Once there, it’s pretty much impossible to go back to our former…

Weeds of Boise: Railroad Tracks Between Kootenai Street and Overland Road

Weeds of Boise: Railroad Tracks Between Kootenai Street and Overland Road

Walking along railroad tracks is a pretty cool feeling. It’s also a good place to look for weeds. Active railroad tracks are managed for optimum visibility and fire prevention, which means that trees and shrubs near the tracks are removed creating plenty of open space on either side. Open areas in full sun are ideal places for a wide variety of weed species to grow. Trains passing through can…

Bananas are one of the most popular fruits in the world. Love them or hate them, most of us know what they look like. Despite their global presence, few stop to think about where these fruits come from. That is a shame because bananas are fascinating plants for many reasons but now we can add blue fluorescence to that list.

Before we dive into the intriguing phenomenon of fluorescence in bananas, I think it is worth talking about the plants that produce them in a little more detail. Bananas belong to the genus Musa, which is located in its own family - Musaceae. Take a step back and look at a banana plant and it won’t take long to realize they are distant relatives of the gingers. There are at least 68 recognized species of banana in the world and many more cultivated varieties. Despite their pan-tropical distribution, the genus Musa is native only to parts of the Indo-Malesian, Asian, and Australian tropics.

Banana plants vary in height from species to species. At the smaller end of the spectrum you have species like the diminutive Musa velutina, which maxes out at about 2 meters (6 ft.) in height. On the taller side of things, there are species such as the monstrous Musa ingens, which can reach heights of 20 meters (66ft.)! Despite their arborescent appearance, bananas are not trees at all. They do not produce any wood. Instead, what looks like a tree trunk is actually the fused petioles of their leaves. Bananas are essentially giant herbs with the aforementioned M. ingens holding the world record for largest herb in the world.

When it comes time to flower, a long spike emerges from the main growing tip. This spike gradually elongates, revealing long, beautiful, tubular flowers arranged in whorls. For many banana species, bats are the main pollinators, however, a variety of insects will visit as well. In the wild, fruits appear following pollination, a trait that has been bred out of their cultivated relatives, which produce fruits without needing pollination. The fruits of a banana are actually a type a berry that dehisce like a capsule upon ripening, revealing delicious pulp chock full of hard seeds. Not all bananas turn yellow upon ripening. In fact, some are pink!

For many fruits, the act of ripening often coincides with a change in color. This is a way for the plant to signal to seed dispersers that the fruits, and the seeds inside, are ready. As many of us know, many bananas start off green and gradually ripen to a bright yellow. This process involves a gradual breakdown of the chlorophyll within the banana skin. As the chlorophyll within the skin of a banana breaks down, it leaves behind a handful of byproducts. It turns out, some of these byproducts fluoresce blue under UV light.

Amazingly, the fluorescent properties of bananas was only recently discovered. Researchers studying chlorophyll breakdown in the skins of various fruits identified some intriguing compounds in the skins of ripe Cavendish bananas. When viewed under UV light, these compounds gave off a luminescent blue hue. Further investigation revealed that as bananas ripen, their fluorescent properties grow more and more intense.

There could be a couple reasons why this happens. First, it could simply be happenstance. Perhaps these fluorescent compounds are simply a curious byproduct of chlorophyll breakdown and serve no function for the plant whatsoever. However, bananas seem to be a special case. The way in which chlorophyll in the skin of a banana breaks down is quite different than the process of chlorophyll breakdown in other plants. What’s more, the abundance of these compounds in the banana skin seems to suggest that the fluorescence does indeed have a function - seed dispersal.

Researchers now believe that the fluorescent properties of some ripe bananas serves as an additional signal to potential seed dispersers that the time is right for harvest. Many animals including birds and some mammals can see well into the UV spectrum and it is likely that the blue fluorescence of these bananas is a means of attracting such animals. Additionally, researchers also found that banana leaves fluoresce in a similar way, perhaps to sweeten the attractive display of the ripening fruits.

To date, little follow up has been done on fluorescence in bananas. It is likely that far more banana species exhibit this trait. Certainly more work is needed before we can say for sure what role, if any, these compounds play in the lives of wild bananas. Until then, this could be a fun trait to investigate in the comfort of your own home. Grab a black light and see if your bananas glow blue!

Many of us were taught in school that one of the key distinguishing features between gymnosperms and angiosperms is the production of fruit. Fruit, by definition, is a structure formed from the ovary of a flowering plant. Gymnosperms, on the other hand, do not enclose their ovules in ovaries. Instead, their unfertilized ovules are exposed (to one degree or another) to the environment. The word “gymnosperm” reflects this as it is Greek for “naked seed.” However, as is the case with all things biological, there are exceptions to nearly every rule. There are gymnosperms on this planet that produce structures that function quite similar to fruits.

The key to understanding this evolutionary convergence lies in understanding the benefits of fruits in the first place. Fruits are all about packing seeds into structures that appeal to the palates of various types of animals who then eat said fruits. Once consumed, the animals digest the fruity bits and will often deposit the seeds elsewhere in their feces. Propagule dispersal is key to the success of plants as it allows them to not only to complete their reproductive cycle but also conquer new territory in the process. With a basic introduction out of the way, let’s get back to gymnosperms.

There are 4 major gymnosperm lineages on this planet - the Ginkgo, cycads, gnetophytes, and conifers. Each one of these groups contains members that produce fleshy structures around their seeds. However, their “fruits” do not all develop in the same way. The most remarkable thing to me is that, from a developmental standpoint, each lineage has evolved its own pathway for “fruit” production.

For instance, consider ginkgos and cycads. Both of these groups can trace their evolutionary history back to the early Permian, some 270 - 280 million years ago, long before flowering plants came onto the scene. Both surround their developing seed with a layer of protective tissue called the integument. As the seed develops, the integument swells and becomes quite fleshy. In the case of Ginkgo, the integument is rich in a compound called butyric acid, which give them their characteristic rotten butter smell. No one can say for sure who this nasty odor originally evolved to attract but it likely has something to do with seed dispersal. Modern day carnivores seem to be especially fond of Ginkgo “fruits,” which would suggest that some bygone carnivore may have been the main seed disperser for these trees.

The Gnetophytes are represented by three extant lineages (Gnetaceae, Welwitschiaceae, and Ephedraceae), but only two of them - GnetaceaeandEphedraceae- produce fruit-like structures. As if the overall appearance of the various Gnetum species didn’t make you question your assumptions of what a gymnosperm should look like, its seeds certainly will. They are downright berry-like!

The formation of the fruit-like structure surrounding each seed can be traced back to tiny bracts at the base of the ovule. After fertilization, these bracts grow up and around the seed and swell to become red and fleshy. As you can imagine, Gnetum “fruits” are a real hit with animals. In the case of some Ephedra, the “fruit” is also derived from much larger bracts that surround the ovule. These bracts are more leaf-like at the start than those of their Gnetum cousins but their development and function is much the same.

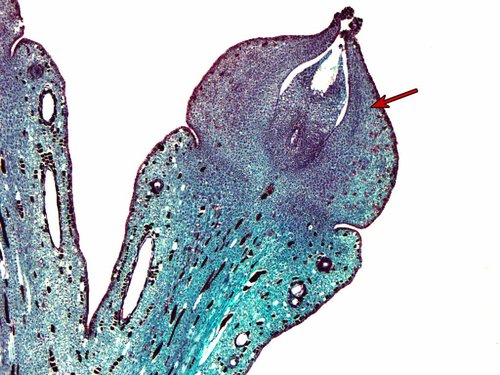

Whereas we usually think of woody cones when we think of conifers, there are many species within this lineage that also have converged on fleshy structures surrounding their seeds. Probably the most famous and widely recognized example of this can be seen in the yews (Taxus spp.). Ovules are presented singly and each is subtended by a small stalk called a peduncle. Once fertilized, a group of cells on the peduncle begin to grow and differentiate. They gradually swell and engulf the seed, forming a bright red, fleshy structure called an “aril.” Arils are magnificent seed dispersal devices as birds absolutely relish them. The seed within is quite toxic so it usually escapes the process unharmed and with any luck is deposited far away from the parent plant.

Another great example of fleshy conifer “fruits” can be seen in the junipers (Juniperus spp.). Unlike the other gymnosperms mentioned here, the junipers do produce cones. However, unlike pine cones, the scales of juniper cones do not open to release the seeds inside. Instead, they swell shut and each scale becomes quite fleshy. Juniper cones aren’t red like we have seen in other lineages but they certainly garnish the attention of many a small animal looking for food.

I have only begun to scratch the surface of the fruit-like structures in gymnosperms. There is plenty of literary fodder out there for those of you who love to read about developmental biology and evolution. It is a fascinating world to uncover. More importantly, I think the fleshy “fruits” of the various gymnosperm lineages stand as a testament to the power of natural selection as a driving force for evolution on our planet. It is amazing that such distantly related plants have converged on similar seed dispersal mechanisms by so many different means.

The plight of the kākāpō is a tragedy. Once the third most common bird in New Zealand, this large, flightless parrot has seen its numbers reduced to less than 150. In fact, for a time, it was even thought to be extinct. Today, serious effort has been put forth to try and recover this species from the brink of extinction. It has long been recognized that kākāpō breeding efforts are conspicuously tied to the phenology of certain trees but recent research suggests one in particular may hold the key to survival of the species.

The kākāpō shares its island homes (saving the kākāpō involved moving birds to rat-free islands) with a handful of tropical conifers from the families Podocarpaceae and Araucariaceae. Of these tropical conifers, one species is of particular interest to those concerned with kākāpō breeding - the rimu. Known to science as Dacrydium cupressinum, this evergreen tree represents one of the most important food sources for breeding kākāpō. Before we get to that, however, it is worth getting to know the rimu a bit better.

Rimu are remarkable, albeit slow-growing trees. They are endemic to New Zealand where they make up a considerable portion of the forest canopy. Like many slow-growing species, rimu can live for quite a long time. Before commercial logging moved in, trees of 800 to 900 years of age were not unheard of. Also, they can reach immense sizes. Historical accounts speak of trees that reached 200 ft. (61 m) in height. Today you are more likely to encounter trees in the 60 to 100 ft. (20 to 35 m) range.

The rimu is a dioecious tree, meaning individuals are either male or female. Rimu rely on wind for pollination and female cones can take upwards of 15 months to fully mature following pollination. The rimu is yet another one of those conifers that has converged on fruit-like structures for seed dispersal. As the female cones mature, the scales gradually begin to swell and turn red. Once fully ripened, the fleshy red “fruit” displays one or two black seeds at the tip. Its these “fruits” that have kākāpō researchers so excited.

As mentioned, it is a common observation that kākāpō only tend to breed when trees like the rimu experience reproductive booms. The “fruits” and seeds they produce are an important component of the diets of not only female kākāpō but their developing chicks as well. Because kākāpō are critically endangered, captive breeding is one of the main ways in which conservationists are supplementing numbers in the wild. The problem with breeding kakapo in captivity is that supplemental food doesn’t seem to bring them into proper breeding condition. This is where the rimu “fruits” come in.

Breeding birds desperately need calcium and vitamin D for proper egg production. As such, they seek out diets high in these nutrients. When researchers took a closer look at the “fruits” of the rimu, the kākāpō’s reliance on these trees made a whole lot more sense. It turns out, those fleshy scales surrounding rimu seeds are exceptionally high in not only calcium, but various forms of vitamin D once thought to be produced by animals alone. The nutritional quality of these “fruits” provides a wonderful explanation for why kākāpō reproduction seems to be tied to rimu reproduction. Females can gorge themselves on the “fruits,” which brings them into breeding condition. They also go on to feed these “fruits” to their developing chicks. For a slow growing, flightless parrot, it seems that it only makes sense to breed when food is this food source is abundant.

Though far from a smoking gun, researchers believe that the rimu is the missing piece of the puzzle in captive kākāpō breeding. If these “fruits” really are the trigger needed to bring female kākāpō into good shape for breeding and raising chicks, this may make breeding kākāpō in captivity that much easier. Captive breeding is the key to the long term survival of these odd yet charismatic, flightless parrots. By ensuring the production and survival of future generations of kākāpō, conservationists may be able to turn this tragedy into a real success story. What’s more, this research underscores the importance of understanding the ecology of the organisms we are desperately trying to save.