#specialcollections

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 3 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is Part 3 of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, if you missed Part 1orPart 2, feel free to check them out first!

Not long after I finished treating my set of 1891 publisher’s bindings (see Part 2), I had the chance to conserve/preserve one of their Renaissance ancestors. The little book shown in Photos 1-2 is a 1541 Latin translation of a text by Aristotle, and its parchment cover is an example of 16th century recycling!

This type of binding is a “limp vellum” laced-in case, and it was made from a sheet of parchment that someone had previously used to sketch architectural columns (see Photos 3-4.)

In Photo 3, if you turn your head sideways, you can see the base of a column near the bottom left corner, and on the right side, near the spine, you can see a drawing of a Corinthian column. These drawings are difficult to see under normal lighting conditions, but the ink (probably iron gall ink) shows up very well under UV. The recycled parchment binding was probably very flexible when the book was bound, but today the cover is stiff and difficult to open. As you can see, it has also detached from the text, and it functions more like a protective folder than a book cover. Apart from this obvious structural problem, the book is in relatively good condition, and I took a minimally-invasive approach to treating it, under the supervision of Lou Di Gennaro, Special Collections Conservator.

I began by adding a few teeny tiny spine linings between the raised bands on the spine of the text block. The book originally had a pair of parchment spine linings, but these are still attached to the parchment text: in Photo 2, a pair of horizontal strips of parchment span the fold in the parchment case. These two strips of parchment were adhered to the back of the text, and this was the main attachment point between the text and the parchment covers. The text could still be handled and read without its original spine linings, but it was more vulnerable to damage (especially because the spine’s loops of sewing thread kept trying to slip off the raised bands!) We decided to apply small strips of Japanese long-fibered kozo paper between the raised bands (Photo 5). I applied these with wheat starch paste (Photo 6) and when they had dried they provided a measure of almost-invisible strength to the spine.

After the spine was consolidated with kozo paper, we considered how to address the binding. It would have been very satisfying to reattach the parchment case to the text… it was clear that this approach would have caused even more damage to the book eventually, though, because of the force that would be required to open it. Fifty or more years ago, conservators might have taken the text apart, washed all of the pages, resewn the book, and given it a brand new parchment cover. In the past, this was considered the best way to preserve a 480-year-old book, but today, most conservators agree that it’s better to preserve these books in their current condition, as much as possible. We decided to leave the parchment cover separate from the text, and to allow it to continue functioning as a protective wrapper. The only difficulty with this decision was that the inside of the parchment cover had several sharp edges that were scratching the outermost pages. Most books have a few blank pages at the beginning and end of the text (“endleaves”), because the first and last pages are very vulnerable to damage. This little book didn’t have any sacrificial endleaves, so we decided to add some (Photos 7-8).

I chose a modern paper of a similar weight and color, and I folded two pieces of it to create a pair of endleaves at both the front and back of the book. Using wheat starch paste, I adhered the folds to the very edge of the first and last pages. The new endleaves look a little too clean when compared to the original paper, but they will protect the first and last pages from abrasion. They can easily be removed from the book later, if another conservator disagrees with this approach, and believe me, there is a long tradition of conservators questioning the decisions of their predecessors! Finally, I created a custom-fit preservation enclosure for the book (Photos 9-10).

This 4-flap wrapper with a rigid outer case will protect the book from light damage, dust, and abrasion, and it’s always better to slap a barcode on the enclosure than on the rare book itself! Additionally, this wrapper will buffer the parchment from fluctuations in temperature and humidity; parchment can shrink or expand quickly, depending on how dry or humid the air is, and over time these cycles of expansion / contraction can weaken the binding. Again, this treatment involved a bit of “conservation” and “preservation.” The physical alterations that I made to the book were minimal, and these changes are more preventive / functional than aesthetic. The preservation enclosure will make the book look a little less pretty on the shelf, but it’s much safer now!

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series… I’ll discuss the preservation of a set of 24 unexposed Daguerreotype plates and the wooden box that they were purchased in (see photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 2 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is Part 2 of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series. If you missed Part 1, feel free to check it out first!

As I mentioned yesterday, “preservation” and “conservation” refer to slightly different activities in libraries and museums, but they both aim to prolong the lives of cultural heritage objects. Often, a conservation treatment can also qualify as a preventive measure (aka preservation), especially when the treatment reunites detached elements or returns a kinetic object (like a rare book) to a functioning state. This return to functionality preserves access to the text, which is especially important for out-of-print books, and those that haven’t been digitized yet. For example, the book shown in the photos below couldn’t be handled or read safely, because parts of it were broken, detached, and in danger of being lost:

This book is an example of a late 19th century publisher’s binding, and unfortunately, these colorful, mass-produced books are usually very fragile today. Publisher’s bindings were made to look attractive without being very expensive, so they were often produced using cheap, poor quality materials. For fragile books like this, damage usually occurs at the spine, because this area absorbs most of the physical stress imparted by reading. The damage shown in these pictures is commonly seen with 19th century publisher’s bindings: the spine cloth is brittle and torn in several places (Photo 1), and the sewing is breaking, resulting in the detachment of several pages (Photo 2). Ironically, this particular book may have been damaged by photocopying or by the process of microfilming, an outdated preservation technique that was popular in libraries until the advent of digital imaging. The simplest way to preserve this book might be to give it a custom-fitted box, which would protect the book from further harm and would hold all of the fragments together. Another way to preserve a book is to repair the damage and restore its function, in other words, to conserve it!

Under the supervision of Dawn Mankowski, Special Collections Conservator, I began conserving this book by carefully removing the book’s original spine lining, a piece of printed waste paper that was probably cut from an 1890’s magazine (Photo 3). This is much easier to do when the spine cloth is already torn! I put this interesting scrap aside, and I strengthened the spine with a new, stronger lining of Japanese long-fibered kozo paper (Photo 3). Next I took the detached pages and resewed them into the book, through the newly-strengthened spine. I then adhered the spine’s original printed waste lining on top of the work I had done, to ensure that none of the book’s original material was lost. Now that the structural work on the spine was finished, I could tackle the main aesthetic problem: the torn spine cloth. I laminated two sheets of kozo paper to make a thicker and stronger sheet, and I toned this laminated sheet dark blue with watered-down acrylics. I gently lifted the cloth away from the board joints and I adhered my blue kozo paper underneath the cloth on one side of the book (Photo 4). After the adhesive was dry, I molded the kozo paper around the curved spine and adhered it underneath the cloth on the other side of the book. I then adhered the original cloth fragments on top of the blue kozo paper, which acts as an invisible bridge underneath the torn cloth. Now the book can be handled and read without fear of exacerbating the old damage.

This was obviously a “conservation” treatment, because it involved a relatively invasive physical intervention to repair prior damage. This treatment has a significant element of “preservation” however, because all of the book’s original material was secured against loss, and the book’s kinetic function was restored, ensuring the preservation of the text. (Of course, another copy of the novel has been digitized and isavailable for free online, but you get the idea!) Throughout this process, I used water-based adhesives like methylcellulose and wheat starch paste, so that my work can be undone or redone by another conservator in the future. In book and paper conservation, we try to avoid synthetic adhesives like polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) as much as possible, because these tenacious glues are very difficult to remove. When we decide to conserve an object, we always strive for “reversibility” (or, more realistically, “re-treatability”) just in case our repairs fail or they cause unexpected harm to an object. Although it’s impossible to completely reverse the damage that occurred to this book over the course of 130 years, I have hopefully prevented the damage from worsening!

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series: I’ll discuss the conservation/preservation of a book published in 1541, bound in recycled parchment (see photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 1 :)

Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

I’m Cat Stephens, an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow studying Library & Archive Conservation at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts. At the IFA, I’m earning an MA in the History of Art and Archaeology, and an MS in the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, specifically in the conservation of books, paper objects, and photographs.

Students in my graduate program have the option to spend their year-long graduate internships almost anywhere in the world, but I chose to stick around and intern at the NYU Libraries’ Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department… In addition to being awesome at their jobs, the conservators here are excellent teachers, and I’ve always been impressed by the range and volume of treatments that they perform every year! Additionally, NYU has done an impressive job of reducing the spread of Covid-19 on campus, and I feel very lucky that my internship was not severely impacted by the University’s precautionary measures. Since September 2020, the library’s preservation staff and I have had the option to work in the library for 2-4 days every week, and we catch up on paperwork during our teleworking days.

Over the last seven months I’ve worked on many treatments that have helped me understand the finer points of library preservation, and I’ll describe four of my favorite preservation/conservation treatments for you over the next four days. These treatments include a 19th century publisher’s binding, a 16th century book bound in recycled parchment, a wooden box full of unexposed Daguerreotype plates, and … a skateboard??

But first, unless you’re a library or museum professional, you may be wondering what Preservation Week is, and how does “preservation” differ from “conservation?” For cultural heritage institutions, Preservation Week is a yearly opportunity to draw public attention to the importance of preserving cultural heritage materials of all kinds. These materials may include modern books, medieval manuscripts, audio/visual materials like VHS tapes and home movies, photographs, scrapbooks, textiles, digital data, paper documents, and metal, wood or glass objects, just to name a few. Many of these materials are held in libraries and museums for public enjoyment, but perhaps many more are sitting in our basements and attics! If you have special things at home that you want to preserve, there are many online resources available to you, and I’ve provided links to some of them at the end of this post.

For conservators and other preservation professionals, Preservation Week is a good time to consider the enormous range of objects that we’re tasked with caring for, and to think about new ways to preserve and conserve them for the next generations. In libraries and museums, “preservation” and “conservation” refer to slightly different activities, but they both contribute to the wellbeing of cultural heritage objects. “Conservation” refers to any physical interventions performed on an object, such as cleaning, making repairs, or compensating for parts that have been lost. A conservation treatment can reduce the stains in a flood-damaged drawing, or it can transform a pile of ceramic sherds back into an ancient vase. “Preservation” usually encompasses the activities performed aroundan object which will minimize the object’s chemical and physical deterioration over time. Preservation activities include the making of enclosures to protect objects from physical harm, dust, or light damage, the management of pests, and the careful control of temperature and humidity in storage facilities. Preservation and conservation are two sides of the same coin, and many argue that “preservation” is the broader term which includes conservation activities. This point of view is often held in libraries, where the objects (usually books) are not just static relics of the past, they are vehicles of information; to access this information, books must be handled, and they must be able perform a kinetic function. For this reason, any conservation treatment that restores functionality to a broken book can also be considered “preservation.” Of course, many old or rare books have been digitized and made available online, but even so, scholars often want to verify and augment their online research by perusing the original book… there’s no digital substitute for the real thing :)

Thanks so much for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, where I’ll discuss the conservation of a novel published in 1891 (photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

Some At-Home* Preservation Resources:

American Institute for Conservation (AIC): “Caring for Your Treasures”

American Library Association: “Saving Your Stuff”

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency): “Salvaging Water-Damaged Family Valuables and Heirlooms” … (Fact Sheets are available in English, Chinese, Vietnamese, Haitian Creole, Portuguese, and Spanish):

Minnesota Historical Society: Preserving “Clothing and Textiles”

National Archives: “How to Preserve Family Archives (Papers and Photographs)”

*But sometimes a problem is so complex that it requires a conservator… AIC’s “Find a Conservator” tool can help!https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/find-a-conservator

First and Second Edition copies of Thea von Harbou’s dystopian classic, Metropolis, the basis for the iconic 1927 Expressionist film by Fritz Lang (von Harbou’s husband). The second “photoplay” edition features stills from the film. From our collection of Utopian Literature [PT2615.A62 M4 1926 and PT2615A62 M487 1927] #dystopia #utopia #metropolis #specialcollections #iglibraries

Post link

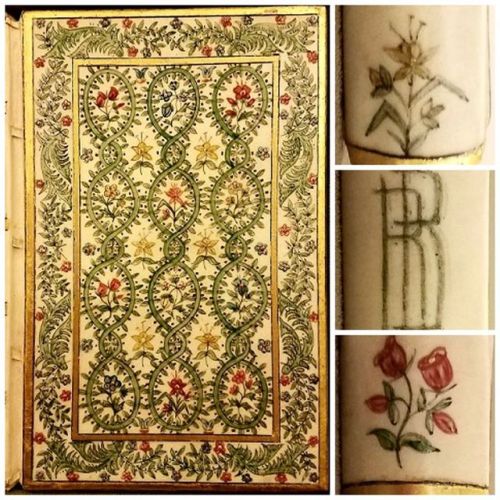

A beautiful #finebinding of Poetical Works of Robert Browning from the #lisabaskincoll. The binding was done by Zaehndorf’s of London for the Royal School of Art Needlework. The binding is hand- painted #vellum over stiff board that includes vine and flower motifs and the initials RB. #specialcollections #librariesofinstagram #bookbinding

Post link

From: The decorator and furnisher. New York : E. W. Bullinger, 1882-1898

NK1700 .D5 Dec. 1886

From: Beverley, Robert, approximately 1673-1722. The history of Virginia. London : Printed for F. Fayram, J. Clarke, and T. Bickerton, 1722

F229 .B62 1722

From: Newman, John B. The ladies’ flora. New York : T.L. Magagnos, 1850s

QK50 .N5

From: Stokes, J. The complete cabinet-maker and upholsterer’s guide. London : Dean & Munday, 1838

TT197 .S8 1838

#MiniatureMonday

#PatSweetSeries

Vampire Hunter’s Kit

Happy Halloween (a day late)!

This impressive work is the final miniature from our Pat Sweet series, and it’s worth the wait!

This kit comes with everything a very small vampire hunter would ever desire for the slaying of equally tiny vampires!

It includes four books (all handstitched, with readable text) on the Uncanny, including Compte d'Erlette’s Culte des Goules and a journal, that ends in a crimson splash, and the warning to the next owner “DO NOT LET HIM LIVE”.

“Stained walnut box partially covered with draped brown kid leather with brass fixtures, filigree protective corners, clasp, and bat-shaped handles. Maker’s label on interior of box: Jos. Nightengale & Sons, Supernatural and Metaphysical Supplies, Mordwyth, Yorkshire.” –Catalog

Hope everyone had a great Halloween!

^Stay safe from mini Vampires, little kitten!

–Diane R., Special Collections Graduate Student