#tar-miriel

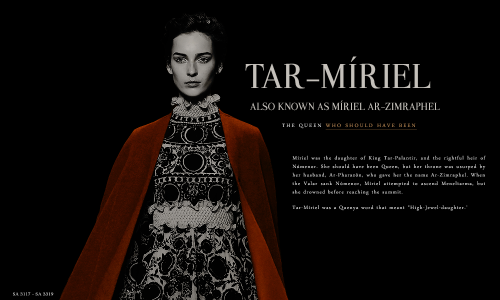

Tar-Míriel was the daughter of Faithful King Tar-Palantír and should have become the fourth Ruling Queen of Númenor. She herself would have continued her father’s stance, but her cousin Ar-Pharazôn usurped her throne and rule, eventually bringing about the ruin of the island through Sauron’s plotting. She died in the Downfall of Númenor.

Post link

AoAA: The Zigûr in the Court of Ar-Pharazôn– RivkaZ 2016

Sauron addresses Ar-Pharazon and Tar-Miriel in the court of Armenelos.

Post link

Huevember Day 22.

And last of all the mounting wave, green and cold and plumed with foam, climbing over the land, took to its bosom Tar-Míriel the Queen, fairer than silver or ivory or pearls. Too late she strove to ascend the steep ways of the Meneltarma to the holy place; for the waters overtook her, and her cry was lost in the roaring of the wind.

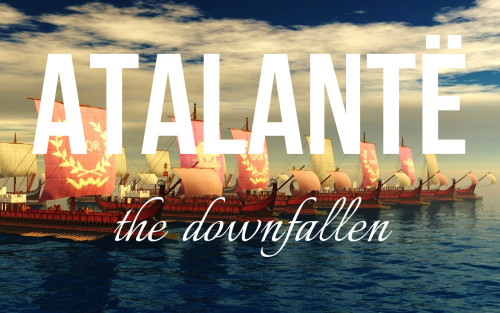

And men saw his sails coming up out of the sunset, dyed as with scarlet and gleaming with red and gold, and fear fell upon the dwellers by the coasts, and they fled far away… Then he sent forth heralds, and he commanded Sauron to come before him and swear to him fealty.

And Sauron came.

– Ar-Pharazôn (Mark Strong) and Tar-Míriel (Leila Nda)

Post link

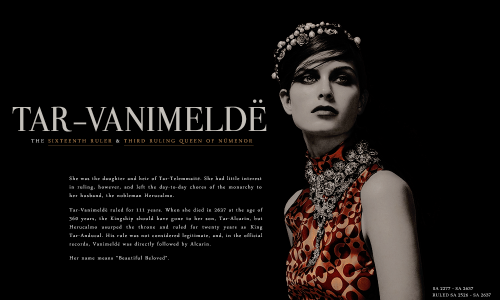

The Ruling Queens of Númenor were Dúnedain women who ruled the kingdom of Númenor. Out of its twenty-five rulers, only three were female. In the early days of Númenor, succession followed the principle of agnatic primogeniture that is, rule passed to the oldest male offspring of the King. Tar-Aldarion, the sixth ruler of Númenor, had only one child: a daughter, Ancalimë. To prevent the throne from passing to his nephew, Soronto, he changed the law to allow full cognatic primogeniture, under which rule would pass to the oldest child of the ruler, whether male or female. (x)

Post link

Tar-Míriel my poor little meow meow I want to understand you.

Some day Míriel will rule the world.

This has been known since she was small, when her father’s efforts to fill his house with faith-filled children failed. It is not his fault or mothers’s, they started late. His father, Tar-Telemnar, threatened to take his children to the palace and raise them against the Faith; it wasn’t until the old king was too ill to carry out his threats that they dared have Míriel.

Even knowing the impossibility, she often prays to the Allfather for a brother (or even a sister!) too take the scepter from her. The world is such a large thing to hold. She’d prefer to rule Rómenna, or her Armenelos at a stretch. Cities can be cupped in the palm of your hand, if you stand somewhere tall enough. No one except the Star Queen can scoop up Arda—even Eärendil is not far enough to view the whole expanse of mankind’s domain. At least that is what the astronomers tell her.

She has to spend a lot of time with the astronomers, the architects, the legal scholars, the city officials, the mariners. Because she will someday rule the island and all its territories her education is thrice as intensive as that of a normal girl.

Her primary tutor is the head of Armenelos’ foremost college for young boys. He teaches her history, the complexity of law, the basics of natural philosophy. For more intricate lessons she must turn to experts in each field, or sit at her father’s feet and simply listen to his daily toiling.

When Father goes to his tower in the west, his regent, a good man, a Faithful man, who harbored elf ships even in the worst days of the crackdown, rules in his place. The petitioners get rowdier then; Míriel watches as they posture, pretending that the king is gone forever when he’s only been out of the city for a week.

Listening to the Navigators’ Guild blustering and the Army threatening is enough to put anyone off the idea of rulership. When the stress gets to be too much, Míriel runs to her mother. She knows no one else with a clearer sense of responsibility, and its boundaries.

“The Faith needs you, and you need them,” Mother tells her as she plucks her eyebrows thin and paints her hairline low—anything to hide the aging gauntness to her face. “If you abandon them, they’ll abandon you, and you’ll be alone, a lamb left out for eagles. Your uncle would gladly slit your throat and step over your body to take the throne.”

Uncle Elrond (he prefers Gimilkhâd but she can only call him that outside the palace) is always kind to her, so aggressively, insistently kind that she cannot help but believe her mother’s characterization of him.

He’s not as honest as his son, who pushed her into a puddle and called her an elf-whore when they were seven. His behavior has improved significantly since he befriended dear Amandil, who could reform the Dark Spider herself with a cup of tea and a few gentle words. Now Calion is, tentatively, a friend, but still a brash bully, the sort to drive a servant to tears and then spend the rest of the day apologizing. Of the two she prefers an unambiguous unkindness to sweet words without substance—better a knife in the front than in the back.

“What if I gave it to him?” she asks. Mother allows these questions, whereas the mere idea of turning over all the progress the Faith has made would send Father into a spiral of anxiety; Míriel loves him too much to ever hurt him like that.

Eyebrows and hair done, mother moves onto the small wrinkles around her eyes, filling them in with a thick creamy makeup and then powdering over the top, adding spots of blush high on her cheeks. “He’d still probably kill you, or lock you up somewhere, or marry you to one of his lapdogs who would treat you as your grandfather treated your grandmother.”

Míriel learned of the indignities heaped upon Inzilbêth by her husband before she could walk, the way she learned the names of the Valar and persecution of the Faithful. Her catechism was a long story of suffering. Often her grandmother would narrate it in person, telling Míriel how she was separated from her eldest son once her beliefs were discovered, how her younger son was taken from her so young that he forgot her face, how her allowances were reduced and she was exiled to a corner of the palace, how her servants were fired and blacklisted from future employment.

The idea of peace and quiet, an escape from a marriage she clearly resented, always seemed nice to Míriel. When she voiced this one day, Grandmother’s lips puckered. Two mornings later she introduced Míriel to another old lady, equally frail and wrinkled but with weathered hands when she took off her decency gloves, and the deep tan of a seaman cast across her features.

At Grandmother’s prompting, the woman spoke of her life; she’d been one of Grandmother’s maids, hired shortly before it had all fallen apart. Afterwards she’d been able to find no work with any decent family, not as a maid, a cook, or even a laundrywoman. Her husband had thrown her out, and she’d been left alone with a young daughter. She’d taken a job on the docks weaving coarse canvas sails but because of the many slaves brought from the territories, whose cheap and nimble labor drove down wages, she’d barely been able to afford bread. Finally she’d given her daughter to a friend desperate for a child and hidden on a cart bound for Rómenna, where Grandmother’s family had helped her find a place in a respectable household.

“A queen’s fall is mostly cushioned by those below her,” Grandmother had said ominously, “She pays half the price her followers do.”

It had terrified Míriel. Under circumstances like these, how could anyone want to be queen?

“It’s not about what you want,” Mother says, for she has a large measure of the foam-blood, that divine gift of the kings, in her veins. She often responds to what your heart says, instead of your lips. “A birthright is not a gift, it is a demand. By birth is is right that you take this.”

“So many birthrights, eventually I’ll have a birthleft,” Míriel mutters mutinously, flinging herself onto an oversized pouf, stuffed with ostrich feathers from a southern colony. The downy dust it throws up makes her nose itch.

Mother is not impressed— birthrights are her favorite topic. Whenever Father takes Míriel up the Meneltarma the first thing he says afterwards is always “See what wonder the Valar have given us?” It is a little tradition, and the traditional response is for mother to scoff.

“They did not give us anything we did not deserve. Our land and supremacy are not a favor, Princess, they are the payment for our ancestor’s sacrifice, weregild for a father taken from his son. A gift is granted, a debt is owed, yet it is only yours if you can collect it, it only stays yours if you can keep it.”

“Then we must thank the Allfather,” Father always continues, insistently cheery. “For without him we would not be here to make demands of such great beings, to owe or collect, see or appreciate.” Only then will Mother nod, for she’s a purist at heart. She’s fond of the Valar, fonder of Uinen, but Eru alone she worships.

Now she just scowls, pinning Míriel with her piercing gaze as if she can beam the memory of a hundred childhood lessons back into her brain. Though she holds out in silence for a few minutes— longer than most people beneath Mother’s stare— Míriel eventually wavers.

“Why must the world make so many demands of me?” she asks, aware that she sounds silly, like a child denied sweets.

In the silver backed mirror, Mother rolls her eyes. “Because you have been raised in palaces, with silk dresses and lamb in your bowl every evening. Because the Allfather wills it. Because you are unlucky.”

Mother is good for feeling out the edges of political possibility, she’s just not very sympathetic. For consolation and cuddles, Míriel goes to her Nurse.

Nursey has taken care of her since her infancy, soothing her at night, putting her to her mother’s breast and then taking her away, playing with her during those first lonely days in Armenelos when Father ascended the throne and the world was in chaos, when Míriel was a political target to be locked in a small courtyard away from danger. These days, with so much education on her plate and the responsibilities of rulership looming, Míriel does not see her often. But Nursey still lives in the palace, while other old servants might retire to stay with their families, Nursey has remained, for she has no family in Númenor.

She never actually speaks of her home— when Míriel was younger she would ask but she quickly learned to leave the topic alone. It’s not unusual for freedmen to be sensitive about their origins. Father’s ban on slave markets (public markets, he still struggles to crack down on private sales and covert importation through smaller ports) has slightly lessened the prejudice against Low Men but resentment lingers. And there is sorrow as well, even if Westernesse is the greatest land, most beloved of Eru, foreigners still miss their homes.

Nurse has never revealed what her life was like before Míriel’s father rescued her. Míriel had to coax the story of her purchase out of Grandmother on one of her gossipy days.

Back when he was Inzildûn, Tar-Palantir would sometimes lurk by the great flesh markets at port. His guilt drove him, though there was little he could do as a prince except watch in misery. “A waste of time,” Grandmother opined, though she conceded that he sometimes found those too injured or old to be auctioned and convinced the sellers to let him take them for free. His household was full of the unfashionably elderly and damaged in those days; and the fear of catching death helped keep his father from interfering too much with him.

Nursey was not so old to be frightening, or so hurt to be helpless, at least not then. She must have been young, given how fast the mayfly men of the territories age. Míriel’s earliest memories suggest she was beautiful as well. And though she cannot possibly have any foam-blood, no gift from the ancient kings, no calling of Elros’ line, she has witchcraft of her own, for that day she found Father amid all the other faces in the crowd and stared at him, unblinking. Frightened that his thin disguise had been seen through and that his identity would be revealed, he’d brought her home, where she’d promptly taken over his hospice of ailing men.

In Rómenna, when Father married Mother, she’d helped run the household, even bringing cakes outside to the spies Tar-Telemnar sent to watch them. When Míriel was born she’d watched her every moment with all the care she gave the dying.

Now, Nurse is in the process of dying herself. Oh, it’s a slow decline. It may take decades more. But it’s all the more fascinating to Míriel for its honesty. Unlike Mother and Grandmother, she never hides her wrinkles. She des not dye her silvering hair black, wear wigs to cover up her thinning scalp, or pin back the sagging folds of her face with tiny needles.

The Faithful do not fear death, that old and gentle friend, but they do not welcome the lingering house guest age either. Death comes once, a sudden absence, and it is undeniably a gift from Eru. Age goes on and on, stealing one faculty after another. Some sects argue that it is not even Eru’s own working but a ploy of the Dark Lord.

Yet Nursey goes around with her paper skinned hands bare. She laughs with her crackling old lady voice and bares her worn, yellowed teeth. She does not seem to realize what is being stolen from her, even though she is surrounded by others who age slower, who are more blessed. It fascinates Míriel, she cannot stop returning to the concept, picking at it like a scab.

Now, as Míriel curls in her lap, Nurse’s arthritic hands pet her hair and she whispers soothing nonsense. “There, there,” and “you’ll be all right, a good strong girl like you.”

“What if I don’t want to be strong?” Míriel asks, muffled by Nurse’s apron. The hands in her hair still.

“My bitterness, some of us never get a choice.” Nursey has never scolded her, even the hint of reproach in her voice makes Míriel curl up in shame.

The kingdom must not fall, the White Tree must not die, the line of Eärendil must go unbroken. Númenor must continue to share its prosperity with the world, must continue to recover from the days of paranoia and hatred that drove the elves from their shores. All this is their fate, their truest destiny, for they were elevated to elevate other men.

Yet Míriel sometimes wishes her birthright did not come with so many dangers attached, she wishes ruling the world did not come with the possibility of dooming it. Even her father seems more certain of his choices than she is; and he spends much of his time paralyzed by guilt, staring at the horizon praying for a glimpse of the wandering isle to put his mind at ease. She wishes she were Tindómiel, who spent her days in rapturous prayer, who helped formalize the festival sacrifices and learned all the names of the Valar, and sailed in her last days to parts unknown. Instead she is left as Ancalimë, forever isolated, trapped with those who despise her.

“I was only born so I could be stuffed beneath a crown,” she whines to Nursey. “No one but Eru would love me if I gave it up.”

This is not wholly true. Her father reads her stories and takes her to tend the Tree, and slips her sips of wine on feast days. Her mother takes her down to the beach and shows her how to talk to the sea, how to crack open clams and throw the shells back for Uinen. They shaped her a princess to save the Faithful but they have loved her all the same. Their love just doesn’t exceed their duty, and she wants it too.

“Your Eru put you here, didn’t he?” Nursery’s rasp is like a pat on the back. “Would your god give you anything you can’t handle?”

The right answer, the one Mother and Father and Grandmother would expect, is No. But Míriel has read her history books, the old stories of brutal times before the land was given to Númenoréans, the more recent ones of dirty deeds that somehow took place on the most blessed island in the world. If even the Allfather’s chosen—Túor and Huor, Tar-Alcarin whose own father turned against him, Tar-Ardamin who was assassinated young— can live impossible lives ordained by the gods then Míriel is surely doomed.

“He would give me death,” Míriel tells Nursey, who cannot understand the impossible position the Allfather is held in. “And it would be called a gift. He has given me the world though he knows I cannot keep it.”

Try as she might to rule it, existence will always slip like water through her hands.

“There, there,” Nurse sighs. “Better to rule than look on helplessly as others do, you’ll learn that someday.”

My@officialtolkiensecretsanta gift for the wonderful @lavender-lighthouses<3

One o your favourite characters is Tar-Míriel, whom I have never drawn but was very excited to!It’s always great to look up other people’s favourite characters, whom you might have verlooked before :)

Happy Holidays everyone, and a happy new year!

Post link

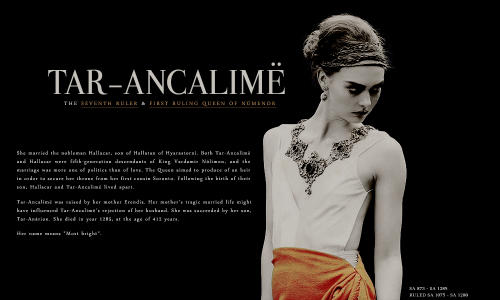

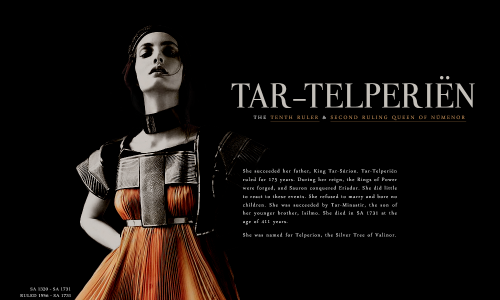

Queens of Numenor ⤅ Míriel

Miriel was the daughter of King Tar-Palantir, and the last rightful heir of Númenor. She should have been the fourth ruling queen of Numenor but her cousin, Ar-Pharazôn, userped her throne and forced her to mary him. Miriel died in the destruction of Numenor. It is unknown if she had any children.

Post link

tolkien south asian week day five | nazgûl ♦ foils |the witch-king and the chancellor |@arwenindomiel

The Nazgûl were they, the Ringwraiths, the Enemy’s most terrible servants; darkness went with them, and they cried with the voices of death.

―The Silmarillion, “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age”

Post link

Tar-Míriel be like: I know Tar-Mairon is obviously plotting my husband’s downfall but tbh so am I. mlm wlw solidarity.

Tar Miriel and Tar Mairon on their way to ruin Ar Pharazon’s life: