#vetdownunder

Seven Species of Sea Turtle

Last year I was lucky enough to visit Sri Lanka and spend some time on the beautiful coastline. The water was so crystal clear and I was delighted to spot the odd turtle foraging close to the beach. I spent literally hours with my eyes glued to the water, waiting for them to pop up for a breath so I could catch a glimpse or snap a pic.

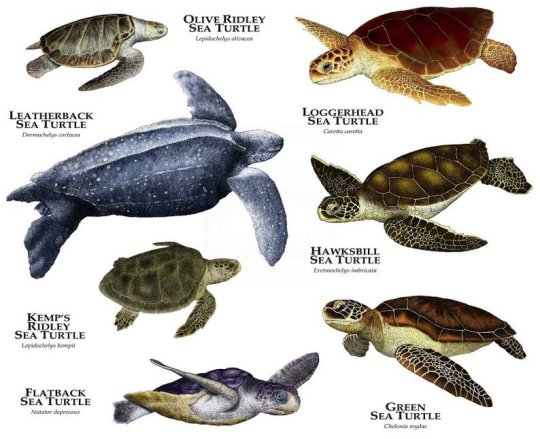

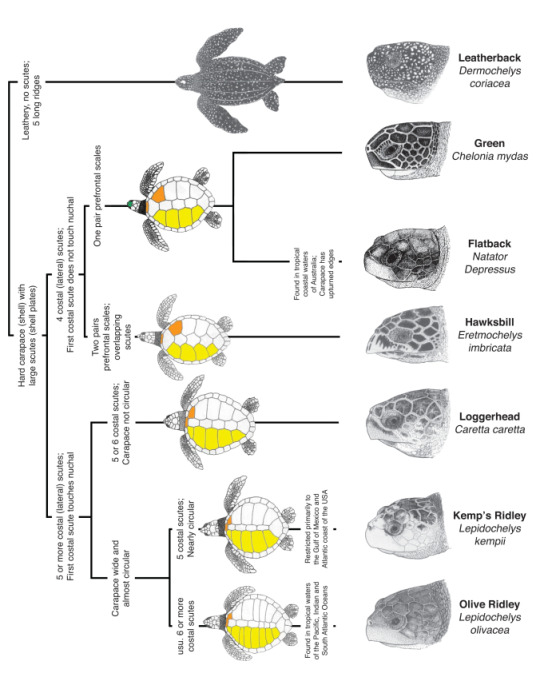

There are seven species of sea turtles currently in existence: leatherback, green, flatback, hawksbill, loggerhead, kemp’s ridley and olive ridley. Of these, six inhabit Australian waters. The IUCN classifies the hawksbill and kemp’s ridley turtles as critically endangered, the green turtle as endangered, and the other four as either vulnerable or data deficient. Some of the threats to sea turtles include poaching, bycatch, development, plastic debris, oil spills, climate change, predators and disease (namely fibropapillomatosis).

While the leatherback turtle has a unique appearance due to its size, huge front flippers and lack of a hard shell, the other species are a little more difficult to differentiate. Identification is done by counting the costal scutes (bony plates on the shell) and the pairs of prefrontal scales.

Looking at my turtle photos, I can count only one pair of prefrontal scales, which narrows it down to green and flatback. The latter is only found around the northern coastline of Australia, SO green sea turtle it is!

If you’re interested in learning more about sea turtles or want to contribute to their conservation, there are countless programs out there for vets, students, nurses and budding conservationists, where you can get hands on experience looking after turtles in rehabilitation centres, collecting data for research, protecting turtle nesting sites or cleaning up their habitats!

Post link

Most of my posts from the past year have been about my final year rotations and my experiences in each. Someone recently asked me to explain what rotations actually are and what they involve. I thought I’d take this opportunity to demystify the structure of vet school to any aspiring vet students out there. The following is based on my course in Australia, a 5 yearcombinedundergraduate(Bachelor of Science, BSc) and postgraduate(Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, DVM) degree, although many vet schools follow a similar system.

FIRST YEAR

Who am I and what am I doing here?

First year is, to put it bluntly, a bit of a waste of time. It comprises basic foundation units which are not at all veterinary related. I had cell biology, statistics, agriculture and even a unit called ‘What is Science?’, which left me more confused about science than before I began! I found myself twiddling my thumbs waiting for this year to be over so I could learn something relevant to my chosen profession.

The next few years of vet school are dedicated to learning (and cramming) theory - all the ‘-ologies’ (physiology, parasitology, pharmacology and so on). This is accompanied by placements, where students spend several weeks on farms and at veterinary clinics in order to gain experience in agriculture and practice. The number of placement weeks varies between courses. Mine entailed 7 weeks of farm placement and 15 weeks of clinic placement.

SECOND YEAR

What does a normal animal look like and how does it work?

Second year covers primarilyanatomyand physiology, as well as microbiology, parasitology and biochemistry. My lasting memories of this year involve rote learning the names of every bump on every bone and every detail of every organ in every species, to the extent that I could draw and label the outside and inside of any animal from memory.

THIRD YEAR

What does an abnormal or diseased animal look like and how does it go wrong?

After learning the normal body inside out in second year, this year is spent learning everything that can go wrong with the body - pathology. One of my units was called ‘Systemic Pathology and Medicine’, abbreviated to SPAM, which ruined the the Monty Python sketch (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gxtsa-OvQLA) for me forever. Pathology is accompanied by radiography, pharmacology, nutrition, toxicology, behaviour, welfare, an introduction to One Health, and the basics of surgery and anaesthesia.

In my course, a research project was also launched towards the end of third year, to be conducted throughout fourth and fifth year. This is a requirement of the masters level postgraduate degree (the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, DVM).

FOURTH YEAR

How do I fix an abnormal or diseased animal?

Fourth year is the dreaded year from hell, when students spend more time in the lecture theatre than they do at home. We often brought sleeping bags, pyjamas and kettles to class and basically moved in for the year. Lectures cover surgery, diagnostic imaging, theriogenology (reproduction) and medicine (small animal, production, equine, wildlife and exotics). This is the year when everything from the past four years starts to come together and students begin to feel like real vets.

FIFTH YEAR

Let’s give it a go!

During fifth year, students finally get to close the textbooks, step out of the lecture theatre and put all that new knowledge into action. This is the year you’re allowed all the fun of being a vet, but with just a fraction of the responsibility! It’s also the last chance to try things under supervision before you do it for real out in the big bad world.

The final year of my veterinary course (and most others I’m aware of) primarily consists of rotations. Veterinary medicine covers an enormous range of fields compared to that of human medicine (think of all the human medical specialties and then factor in all the different species vets look after). Rotations are short (one or two week) blocks dedicated to each major field or speciality of the veterinary industry. They are designed to provide students with a foundation in all aspects of the profession. The year group is divided into small groups of around eight students which rotate between 15 different rotations (listed below). These amount to a total of 24 weeks. During these rotations, students form part of the department’s veterinary team and have the opportunity to develop their skills in each area with the guidance of experienced vets. For example, during the two week equine rotation, students may accompany vets on lameness call outs, treat a foal in the hospital, or scrub into and assist with a colic surgery. Whereas, during the two week diagnostic imaging rotation, students may position a surgery patient for stifle radiographs, evaluate an echocardiogram, or radiograph the fetlock of a lame horse.

The other component of final year is streaming. A stream is a broad division of the veterinary industry by species: small animal, production animal, equine, mixed, and wildlife and zoological medicine. Students elect one stream in which to advance their knowledge and skills during final year. This is either the field the student wishes to pursue as a graduate vet, or simply one they have an interest in. A further 12 weeks of placement is undertaken in this field during final year. I selected the wildlife and zoological medicine stream, which allowed me to research platypus in Tasmania, spend two weeks with the vets at my local zoo and participate in wildlife field operations in South Africa.

- Primary care

- Small animal medicine

- Surgery

- Anaesthesia

- Diagnostic imaging

- Ophthalmology, shelter, wildlife and behaviour

- Emergency and critical care

- Dermatology and dentistry

- Equine

- Production

- Intensive industries

- Public health

- Anatomical pathology

- Clinical pathology

- After hours

I hope this post provides a bit of an insight into vet school and what to expect each year. To find out more about each rotation, have a read of my previous posts. As always, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to ask.

24 weeks of rotations, 15 weeks of placement, 1 postgraduate research project, over 50 assessments, 12 flights and 3 final exams later, I’ve finally reached the end of fifth year! We hit the ground running immediately after our fourth year exams and worked tirelessly right up until Christmas. Although I didn’t have a moment free to appreciate it at the time, fifth year gave me the freedom to explore my interests and presented countless opportunities to travel and work abroad. My experiences have allowed me to grow as a vet - taking charge of cases, making my own decisions and taking responsibility for the outcome. The past 13 months have without a doubt been the highlight of vet school.