#vetstudentlife

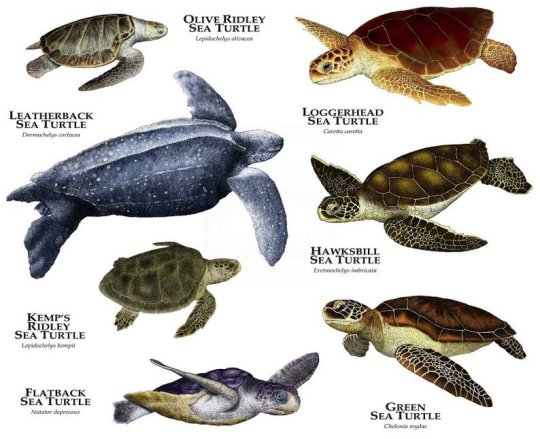

Seven Species of Sea Turtle

Last year I was lucky enough to visit Sri Lanka and spend some time on the beautiful coastline. The water was so crystal clear and I was delighted to spot the odd turtle foraging close to the beach. I spent literally hours with my eyes glued to the water, waiting for them to pop up for a breath so I could catch a glimpse or snap a pic.

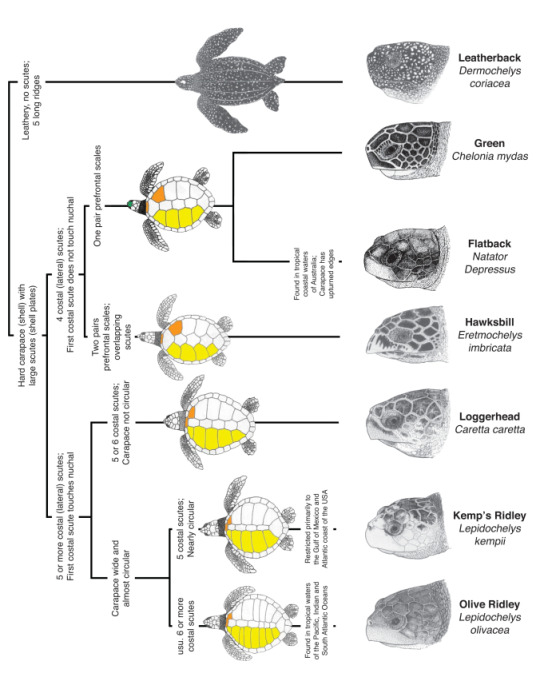

There are seven species of sea turtles currently in existence: leatherback, green, flatback, hawksbill, loggerhead, kemp’s ridley and olive ridley. Of these, six inhabit Australian waters. The IUCN classifies the hawksbill and kemp’s ridley turtles as critically endangered, the green turtle as endangered, and the other four as either vulnerable or data deficient. Some of the threats to sea turtles include poaching, bycatch, development, plastic debris, oil spills, climate change, predators and disease (namely fibropapillomatosis).

While the leatherback turtle has a unique appearance due to its size, huge front flippers and lack of a hard shell, the other species are a little more difficult to differentiate. Identification is done by counting the costal scutes (bony plates on the shell) and the pairs of prefrontal scales.

Looking at my turtle photos, I can count only one pair of prefrontal scales, which narrows it down to green and flatback. The latter is only found around the northern coastline of Australia, SO green sea turtle it is!

If you’re interested in learning more about sea turtles or want to contribute to their conservation, there are countless programs out there for vets, students, nurses and budding conservationists, where you can get hands on experience looking after turtles in rehabilitation centres, collecting data for research, protecting turtle nesting sites or cleaning up their habitats!

Post link

Surgery Rotation

My final rotation of the year! It seems like yesterday that I was following a hand drawn map of the hospital to locate the ophthalmology room for my very first rotation. How far I’ve come!

On this rotation we began with a small group of four students (rather than the usual eight) which was then divided in half, with two students beginning on soft tissue and the other two on orthopaedics. I was assigned to soft tissue surgery for the first week and it was hectic! My buddy and I were run off our feet trying to complete the work of four students. We arrived at 7:30 each morning and didn’t leave until after 7:00 at night when our patient records were completed. Once home, our evenings were spent frantically researching surgical procedures to avoid looking like complete idiots when the specialists inevitably quizzed us the following day.

Students were assigned to cases and responsible for collecting a history during the initial consultation with the owner, performing a physical examination, scrubbing into the surgery, writing a detailed surgical report, looking after the patient in hospital, administering medications, overseeing wound care, recording vitals and the progress of recovery, and eventually discharging the patient. Our ultimate goal was to get our patients through all of those stages and discharged as quickly as possible, to minimise the number of animals in our care and allow us to leave the hospital at a semi-reasonable hour each day.

Although being a group of just two students meant that we had an insane workload to keep on top of, we did get special treatment in the form of being allowed to scrub into almost every surgery! Students in previous groups were lucky to scrub into five surgeries during the whole rotation, whereas I scrubbed into ten just in the first week! Even so, being specialist surgery, our job primarily consisted of passing surgical instruments and cutting suture material (which was never quite the right length). One day towards the end of the first week, the surgeon surprised me by letting me place two sutures: a simple interrupted and a cruciate. That was two more than my fellow student, so I counted myself lucky!

During the first week, I was involved with a huge variety of soft tissue cases (prepare for big words) including an abdominal hernia repair, ventral bulla osteotomy, two dermoid sinus removals, multiple wound repairs, adrenalectomy, thyroidectomy, melanoma removal and skin flap, tongue biopsy, emergency plication to correct an intussusception, gastropexy, and ovariohysterectomy.

The most memorable case from this rotation was a soft tissue sarcoma removal from the hind leg of an elderly Golden Retriever. The surgery was performed on Monday and I arrived early the following day to find her leg very swollen. Over the week, the leg continued to swell and her condition steadily declined. By Thursday her breathing was laboured and I could hardly hear a heart beat. Our patient was transferred to the ICU to spend the night in an oxygen tank. The following morning she was much the same, still struggling for each breath. The vets had tentatively diagnosed her with von Willebrand Disease, an inherited clotting disorder caused by a defective or deficient protein. This meant the swelling in her leg was likely pooled blood as a result of uncontrolled bleeding from the surgical site. The disorder had never been detected previously and so it was an incredibly unfortunate and unforeseen complication. On Friday evening I went to check on her before heading home and reached the ICU just as someone yelled, “SHE’S ARRESTED!”. The emergency team sprung into action and began CPR. Her owners were contacted and the decision was made to let her go. It was a devastating end to what should have been a simple mass removal. Everyone involved was deeply affected by her death.

At the end of the first week, the resident came to see us in the student tutorial room. He told us we had done a fantastic job and he really appreciated our help. The hard work of final year students is often taken for granted, so the few times people have acknowledged and appreciated my efforts have really stuck with me!

Just as we were beginning to feel comfortable with soft tissue surgery, Monday came around and it was time to switch to orthopaedics. New surgeries, new patients, new team. At least I still had my student buddy for support and entertainment. There was an interesting mix of cases on orthopaedics, including bilateral hip dysplasia, intervertebral disc disease, two medial patellar luxations, shoulder arthroscopy, stifle arthroscopy and joint tap, and many tibial plateau levelling osteotomies.

Over the two week rotation, we had several tutorials on wound management, brachycephalic airway syndrome, neurology and fracture management. On the last Friday we had a short exam, followed by an orthopaedic cadaver lab, where we practiced our surgical approaches to the hip and stifle joints, and performed a femoral head ostectomy (a procedure in which the head of the femur is cut off to remove the hip joint).

The last surgery finished late on Friday and the hospital was eerily quiet. It was the strangest feeling saving my final reports, packing up my belongings and preparing to leave the hospital for the last time. The four of us didn’t really know how to react. We congratulated one another on finishing and headed home in stunned disbelief, unsure whether to laugh or cry. We didn’t have much time to process these feelings before our minds became consumed with panicked thoughts of the impending exams. It was time to put our heads down and bums up for one final push to the finish line!

Post link

Equine Rotation

I was looking forward to being back in the large animal hospital, in my overalls and boots, with the smell of fresh air, hay and manure wafting through the barn. Out of the group of eight students, only two of us had an interest in working with horses, which meant I’d have more opportunities to practice things over the next two weeks. It became evident early on that the equine department had an innate distrust for students and wouldn’t be allowing us to carry out anything but the simplest tasks under extreme supervision. This sentiment was only reinforced by a recent incident involving a student and a feisty stallion.

After a brief introductory session, a couple of the equine vets conducted a lameness practical with the assistance of two of the teaching horses. We practiced palpating limbs, using hoof testers, and performing flexion tests. After a couple of hours of trotting horses up and down the asphalt outside the barn, both students and horses were knackered.

Also on the first day, we assigned ourselves to each of the hospital cases which would be our responsibility until their discharge. We were to feed, water, medicate, exercise and groom our charges, take and record their vitals each morning and night, write their hospital records, communicate their progress to the responsible vet, perform any procedures required, and present a case summary to the group at morning and evening rounds. My first case was a two year old thoroughbred filly named Sentimental Queen who had a wound over her left elbow (due to a run in with a fence) and a septic joint was suspected. She was a gentle horse and I really enjoyed looking after her and following her case over the week she was hospitalised.

I am the first person to laugh at the ridiculous names given to horses, and for some reason I got it in my head that my horse’s name was instead Independent Sunshine. I made the mistake of sharing that with my fellow students, who then made it their mission to confuse me into calling her Independent Sunshine during rounds by dropping the two words into conversation just prior. I’m pleased to say they didn’t succeed, though there were often long stretches of silence while I tossed up which name was correct in my head.

After a couple of ultrasound scans, and an attempted arthrocentesis and joint flush, we concluded that the wound didn’t in fact communicate with the joint, which made the prognosis considerably more favourable. Each day I brought her into the stocks, cold hosed her leg for 10 minutes to reduce the swelling, re-bandaged her leg, administered her penicillin intramuscularly and phenylbutazone orally, and gave her plenty of love and attention. The swelling over her elbow gradually reduced, as did her temperature, and the wound healed steadily.

It often seemed as though the equine staff were out to get us. They just revelled in any opportunity to scold us for the silliest things. One of the hospital patients developed a case of diarrhoea and I enthusiastically volunteered for the glamorous job of collecting a fresh sample. I gloved up, armed myself with a faecal pot, and stood ready for the next stream. When it came, I extended my arm from where I stood safely at the horse’s side, and filled the pot with the green goodness. At that exact moment, about three voices all yelled at me simultaneously to stay away from the horse’s rear. Err… how can I collect a freshsample without standing in the vicinity of the horse’s rear?

It wasn’t long before we got to put our new skills from Monday’s practical class to the test with the endless flow of lameness cases that graced the hospital. Solar abscesses, ligament injuries, joint disease… it was one lameness examination after another! The students watched as a nurse trotted the horses up and down in front of us. We scrutinised every movement, wishing so hard to see a head bob or a hip hike that half the time it was imagined. Just when I thought I’d localised the lameness to a single limb, the horse would trot back and I’d pick the opposite limb. The movements were so subtle that I often doubted whether the vet could see it either. Afterwards they would turn to the group of students and say, “you could see that lameness in the the near fore, couldn’t you?”. “Yes” was the answer, whether we could or not!

During the first week, I went on a couple of call outs with a fellow student, a vet and a nurse. At the first property, the owner was really friendly and while the vet was taking radiographs, she showed us around and took us to meet all her horses. When she introduced a gelding as Dark Romance, I struggled to contain a snigger, but she quickly followed with, “I know the name is ridiculous, he came with it”. Finally, someone who understands the joke, I thought. With a straight face, she continued, “I would’ve named him Demi Devine!”. It was too much. I had to turn away to hide my laughter!

Students also took responsibility for outpatients, and a single student was assigned to each case. When my grey warmblood mare arrived at the hospital, I introduced myself to the owner and attempted to gather a detailed history for when the vet arrived. Each of my questions was met with either a single word or a grunt. The man couldn’t have made it plainer that he didn’t want to speak to me. Of course, when the vet arrived, he became Mr Chatterbox and the history changed entirely. Charming.

Towards the end of the first week, the vet responsible for Sentimental Queen (Independent Sunshine) approached as I was hosing her leg and expressed his delight at her progress. He congratulated me on my work and suggested she could be discharged on Friday. It was really gratifying to receive some praise for my efforts - a rare occurrence for a vet student! Friday rolled around and it was a bittersweet moment when she was loaded onto the float and driven home.

For two weeks I had my fingers crossed for a colic case. Please let me have just one more before I graduate! Finally, on the second last day of the rotation, we had an urgent call from an owner whose horse had been collicking since the day before. Supportive treatment from the regular vet had little effect, so she’d opted to bring him to the specialist hospital. A combination of the signalment, history, physical exam and ultrasound findings lead to the decision to perform an exploratory laparotomy. Our patient was anaesthetised and prepped for surgery. The surgeon allowed me, as the primary student, to scrub in and I couldn’t have been more excited. He suggested I wait until he had opened the abdominal cavity and determined the cause in case it was irreparable. Soon after the first incision was made, a horrible rotten smell filled the room and black fluid leaked from the abdomen. The cause was a strangulating lipoma - a small fatty mass which restricts the passage of digesta and the blood supply to the intestines. The built up pressure had resulted in a perforation, explaining the black fluid within the abdomen. The vet identified an 18 foot section of necrotic intestine which would need to be resected if the horse was to have any chance of survival. Even if that went ahead, the prognosis for recovery was grim. The owner opted for euthanasia, which everyone agreed was the kindest option. Instead of scrubbing in, I changed into my overalls, put a rectal palpation glove on each arm, and helped the vet stuff the organs back into the abdomen and suture it closed for disposal. The job was comparable to stuffing a sleeping bag into a too-small sack - far easier said than done!

As usual, the final day of the rotation was reserved for assessments. After our morning computer exam, we all reluctantly moved into the conference room for grand rounds. This involved each student presenting on a topic related to one of our cases during the rotation. I chose septic arthritis as my topic. Public speaking is not my strong point and I was relieved when it was over.

Mid afternoon, one of the vets informed us that a newborn foal was en route to the hospital. The mare had sadly died during birth and the foal had not received sufficient colostrum. We were all super excited for the new arrival. The foal was less than a day old, yet almost equal to me in weight, with limbs to rival a spider monkey, and a whole lot of attitude! It took four of us to restrain him on his side and stop his knobbly legs from flaying everywhere while we did a plasma transfusion. With the new addition to the hospital requiring constant monitoring and frequent bottle feeds, we had our work cut out for us on the weekend shifts!

Post link

Diagnostic Imaging Rotation

I had been dreading this rotation all year and it was finally upon me. Countless stories of students crying and having breakdowns were circulating and didn’t inspire a great deal of enthusiasm. The first couple of days were really quite overwhelming. It seemed as though there was a new assessment every five minutes!

Each day generally began with an online quiz for which we frantically revised the night before. Once finished, we would convene in front of the light boxes for interpretation rounds. This involved five students being selected at random to look at a series of radiographs we’d never seen before, interpret them using a systematic approach, and arrive at a diagnosis. This was both timed and assessed. Each day would cover a different topic: musculoskeletal, thorax, abdomen, equine, and so on. In a desperate attempt to beat the tears, our group diffused the tension with humour. I don’t remember how it started, but we began referring to interpretation rounds as ‘the grilling’ or ‘the roasting’. The puns were endless. When asked if we were ready, the response was “I’ve been marinating all night!”. As the first person of the day stepped up to the hot seat, someone would mime lighting a grill. If the radiologist was being especially harsh, we’d say “the grill is hot today!”, and if they were giving someone a hard time, someone would make a sizzling noise in the background. Laughter was the only way to get through it.

On the first day, we had a short ultrasonography tutorial and a quick practice scanning a nurse’s dog. Each student was assigned a day of ultrasonography during which we observed the specialist performing scans and pretended to understand the grey shapes on the screen. Another day was spent on ‘interpretations’ where we interpreted all of the radiographs taken that day. The remaining students were assigned to radiography, which involved positioning real patients and taking the radiographs according to requests from clinicians. These were also timed and assessed, with many ways to instantly fail. If there weren’t any real patients, we were assessed on the dummy dog (named Emily) who was frustratingly inflexible. In the evenings, we would convene again for rounds and share any interesting cases with the group.

Towards the end of the second week, we had yet another timed exam where we had to take radiographs of a horse’s foot, fetlock or carpus. I forgot to check the exposure parameters on one of my shots, but it happened to be on the right setting by coincidence. On the final morning, we had an online theory exam.

As much as it pains me to admit it, I think I actually enjoyed diagnostic imaging! It was great to finally learn how to read radiographs and I improved considerably over the two weeks. Not a single tear was shed in our group, which was perhaps our greatest achievement.

Post link

Public Health Rotation

The rotation that converts the masses to vegetarianism! This is a week spent in lab coats, hard hats and gumboots, visiting a range of local abattoirs (chicken, sheep, cow and pig) and learning about public health issues. The following account describes my observations in detail and doesn’t skirt around difficult and controversial issues. If you do not want to know about animal slaughter, stop reading now and find another blog that talks about happy things like puppies and kittens! However, I encourage you to educate yourselves about where your meat comes from so that you can make informed lifestyle decisions. After all, eating animals is a privilege, not a right!

On Monday we were re-introduced to the concept of ‘One Health’ (a multidisciplinary approach to health issues at the human, animal and environmental interface), revised zoonotic diseases (those transmitted naturally between humans and vertebrate animals), and learnt about food safety.

The following day we kicked off the abattoir visits with a tour of a chicken factory. The disposable onesies we were given for hygiene purposes made us look like giant white chickens ourselves. It was a dangerous situation for chicken-lookalikes to be in! Our guide was way too enthusiastic for a slaughter house and seemed to be operating under the illusion that he was instead working at a fun fair. We walked through a set of doors to reveal the most bizarre scene I think I’ve ever seen. Everywhere I looked, there were plucked chickens gliding along on tracks, hanging by their legs, at various stages of disassembly. I was half expecting circus music to start playing in the background. Despite the horror of the situation, I actually struggled not to laugh at the absurdity of it all. After showing us around the meat processing areas, our guide took us to see the slaughter. Groups of chickens were contained in crates, which were passed individually through a gas chamber. The chickens were gassed with CO2 and exited the chamber unconscious. Workers then hung them by their feet, and they moved along the line past a blade which cut their necks, causing them to bleed out. Just before their necks are cut, a muslim man standing with a hand outstretched, touched each chicken as they went by, apparently saying a prayer for them (not that it did any good). This ensures the final product is ‘halal’ certified.

On Wednesday, we all piled into the university vehicles for a long drive down south. Our first stop was a sheep abattoir. This one was quite crowded and we had to jump between moving carcasses, hop over piles of congealed blood, and dodge swinging knives. This abattoir also produces ‘halal certified’ products. The sheep were stunned with an electric stunner before having their necks cut by a muslim man. Workers are supposed to check the corneal reflex prior to cutting the neck, and re-stun if there is a blink response. In the five minutes I spent watching this process, I didn’t once observe anyone checking the corneal reflex, and I am confident that one sheep was not effectively stunned before having its neck cut. This sheep continued to kick and struggle until it eventually bled out. I found this deeply unsettling.

After a quick lunch break at the nearby farmer’s market (I can assure you there was no meat in my sandwich!), we headed to our next stop - a beef abattoir. I had already visited this abattoir in my second year of vet school, so I was prepared for the horrors ahead. Although the sheer size of the animals made it more confronting than the other abattoirs, I was generally impressed with the efficiency and welfare standards. This abattoir also produces ‘halal’ products. The cows are stunned with a non-penetrative captive bolt (NPCB) and their corneal reflexes are checked to ensure they are unconscious. A muslim man performs two cuts: the first is a religious cut across the neck and the second severs the major thoracic vessels causing faster bleeding. The corneal reflex check and second thoracic cut make this method more foolproof than that used at the sheep abattoir. I was surprised by the number of late-term foetuses I saw going around the conveyor belts with the other organs. According to the OPV (on plant vet), these foetuses die from anoxia (lack of oxygen) over about a ten minute period. This didn’t sit well with me. Apparently there is no law against slaughtering pregnant animals, but pregnant animals are not ‘fit to load’ (legally allowed to be transported) during late gestation. This, however, does not appear to be enforced. The OPV explained that the abattoir makes a lot of money from foetal products (such as foetal blood drained from the heart), so there is no incentive to prevent this practice.

It was an emotionally draining day and I decided I had earned some comfort food. I stopped at the grocery store on my way home to buy some chocolate. Just as I got there, I watched a dog run across the road and get hit by a car. I sprinted over and was the first on the scene. The dog was bleeding profusely, an eye was hanging out, and the the owner was screaming and panicking. I tried to assess the dog and take control of the situation. The dog rapidly turned white and I couldn’t feel a heart beat or pulse. It was a quick death, most likely caused by a splenic rupture and huge internal bleed. I left the owners to grieve and managed to hold the tears back until I got home. It was just a bit too much death for one day!

On Thursday, we wrapped up the grand abattoir tour with a visit to a pig abattoir. They were reluctant to show us much, which of course made us assume the worst. However, we did get to see some of the carcass processing post-slaughter. It was a different kind of weird, perhaps because their pink hairless bodies look oddly human-like. The carcasses were hung by the hind legs and moved slowly around a track through all the processing stages. They got dunked in a trough of water, causing it to slosh over the sides periodically, then set alight by a jet of flames which singed off hairs and cleaned the skin, before being disembowelled. Although we didn’t see the slaughter, the method was described to us. Small groups of pigs are gassed in a CO2 chamber which renders them unconscious. Their necks are then cut individually. Larger pigs are stunned with an electric stunner followed by a captive bolt, prior to having their necks cut. Pig products, of course, are not halal, so there were no religious slaughter methods used.

Back at uni, we conducted a quick food hygiene experiment. We inoculated a slab of meat with bacteria and made cuts with a knife to mimic the work of abattoir employees. We then dunked the knife in two different water temperatures and compared the bacterial load between them. The higher water temperature resulted in a significantly reduced bacterial load. This technique of dunking knives in hot water between cuts is utilised in abattoirs to reduce food contamination.

On the final day of the rotation, we did our group presentations on zoonotic diseases. My group was assigned Ebola virus. I found this topic fascinating and really enjoyed researching the disease. During the presentation, I stumbled on a word and got the giggles. I couldn’t stop laughing and every time I managed to gain control of myself, I would see one of my friends shaking with laughter and it would set me off again! Sorry team! After the presentations, we sat a short end-of-rotation exam, which was very reasonable. Much to our delight, we finished early and got the afternoon off!

All in all, I thought this rotation was a confronting but very necessary experience. I think welfare issues regarding slaughter need to be tackled head on. Turning a blind eye is the convenient option, but it doesn’t mean that animals aren’t suffering. Most people today are so far removed from the slaughter process that it’s easy to forget that meat comes from animals rather than the supermarket, and take their lives for granted. I strongly believe that anyone who eats meat should be made aware of the slaughtering process, and ideally witness it. If you can’t stomach the animal slaughter, you shouldn’t stomach the meat!

Have a read of my next post about religious slaughter.

Post link

Have You Got a Job Lined Up Yet?

Fresh off the plane from Sri Lanka, I had a mere three nights in my own bed before re-packing my bags and setting off on yet another veterinary expedition. This time I’d be driving several hours south for two weeks of clinical placement at my favourite country practice. I spent my first ever week of placement at this clinic, and during the drive down it dawned on me that this would be my last! Two more weeks of being ‘the student’. Next time I find myself in a clinic, I’ll have the title and responsibility of ‘veterinarian’!

It was nice to see some familiar faces when I arrived and catch up on some of the country gossip - most of which revolved around sightings of a panther that had escaped from a circus over 70 years ago, and a thylacine (an extinct carnivorous marsupial) *eye roll*. I stayed with a couple of the vets, both of whom I really admire and look up to as mentors, on their new farm just out of town.

The first week was pretty eventful and I saw my fair share of interesting cases and procedures, including a steer with a corneal ulcer, several non-healing wounds, a dog with an acute hepatic injury, two ram castrations, a horse dental float, a cat with pericardial effusion, a lame bull, a sheep with lambing paralysis, lymphoma in a dog, a recumbent horse, and a cow that had retained foetal membranes, metritis, mastitis andpneumonia.

One of the vets introduced me to the clients by saying, “this is Steph - she’s an almost-vet”. Every single person I met during the first week asked me if I have a job lined up at the end of the year. I hadn’t even started looking! I wasn’t at all concerned until now! The vets also started testing my knowledge by saying, “you’re going to be a vet in a few months - how would you treat this case?”. Generally I was pretty wrong, but at least I know the answers now… and I still have five months to learn everything!

The vets I was staying with killed one of their sheep and I spent an evening helping them cut up the carcass. It was quite an experience and oddly relaxing! Their four year old son gave us all an anatomy lesson as we worked. Once every last scrap of meat had been scraped off the bones, we chucked some on the barbecue and had lamb chops for dinner. The real country experience!

One morning during my second week, I had the choice of getting a lift with one of the vets who had a gelding to do, or driving to the clinic myself to help another vet with a lame bull. After much deliberation (and being acutely aware that whichever I chose would be the wrongchoice), I decided on the bull. After listening to the first vet’s car engine fade into the distance, I hopped in my own car and turned the key. It wouldn’t start. Brilliant. I just sat there for a second, mentally kicking myself. Typical! Most of my day was spent getting lifts from other people, on the phone to mechanics, and organising the car to be towed into town. I ended up missing out on going to see the bull anyway, and the other vet rubbed salt in the wound by telling me he had an exciting day involving a foetotomy, prolapsed uterus in a cow, and two equine geldings!

In between frequent trips to the auto shop, I observed and assisted with some interesting procedures during my second week. There was a ferret dental, entropion corrective surgery, a grid keratotomy and third eyelid flap on a dog with corneal ulceration, another equine dental, a couple of colic cases, and a dog with sudden onset blindness in both eyes. The vets let me do a few sterilisation surgeries as well, and I impressed them with my intradermal suturing skills acquired from my recent placement in India. I also got to extract a canine from a cat (the tooth variety, not the barking type).

Towards the end of the second week, the practice owner tracked me down and interrogated me about my interests and plans for next year. It was obviously an interview and everyone in the clinic went quiet to listen in. I was really put on the spot! She explained they had plans to hire a new graduate vet next year and then invited me to dinner the following night. Once she left the room, everyone said, “oooh, she’s sussing you out Steph!”. I was admittedly a little terrified about the invitation, but it was actually very casual and enjoyable. As soon as I arrived, I was put to work drenching their newly acquired sheep. I suspect that was a subtle test as well! We had pork chops for dinner (again, meat from their own pigs). The following day, I accidentally walked in on a discussion between the practice owner and some of the staff about potential candidates for the vet position. I didn’t hear a lot, but I guess time will tell.

Despite my misfortunes, I really enjoyed my final two weeks of placement and learnt a whole lot. Although I’m terrified of graduating and stepping out into the big wide world, I’m also really excited about becoming a vet in just a few short months. It’s time to dust off the old CV and start hunting down some referees!

Post link

Rabbit Cadaver Workshop

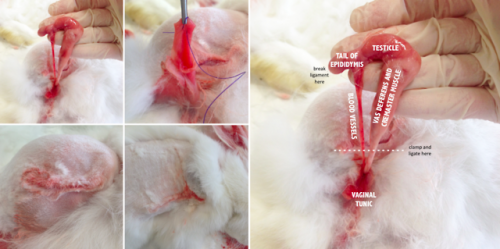

Yesterday I went to university for the first time in three months. It was a strange feeling being back, especially on a Sunday! I joined a small group of my classmates for an optional rabbit workshop lead by an exotic animal veterinarian. Using rabbit cadavers, we learnt how to perform castrations, limb amputations and dental extractions. It was a fantastic opportunity to practice these procedures under close supervision and without any risks to the patient. It was also great to catch up with a few of my friends who I haven’t seen in yonks! For my own benefit more than anything else, here are the procedures for rabbit castrations and limb amputations.

Castration

- Clip and scrub surgical site

- Scrotal incision: incise vaginal tunic and exteriorise testicle (open castration)

- Identify structures (vas deferens and cremaster muscle are together, blood vessels are separate)

- Separate the tunic from the tail of the epididymis by breaking down the ligament

- Clamp spermatic cord

- One cerclage ligature in crush mark

- Remove testicle

- Close tunic with cruciate suture

- Apply digital pressure to skin edges (no need to suture)

Hindlimb Amputation

- Circumferentially incise skin and muscle at level of stifle

- Ensure patella is removed (if ligament is cut distal to patella, patella will shoot proximally)

- Blunt dissect muscle away from femur

- Use a bone saw to cut femur, leaving about one third of the length

- Suture muscle, subcut and skin (intradermal skin sutures)

Forelimb Amputation

- Incise skin along scapular spine

- Circumferentially incise around limb

- Dissect supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles off scapula and dissect beneath scapula

- Remove forelimb

- Suture muscle layer closed

- Suture subcut and skin (intradermals) in upside down ‘T’ shape

Post link