#wellesley in the world

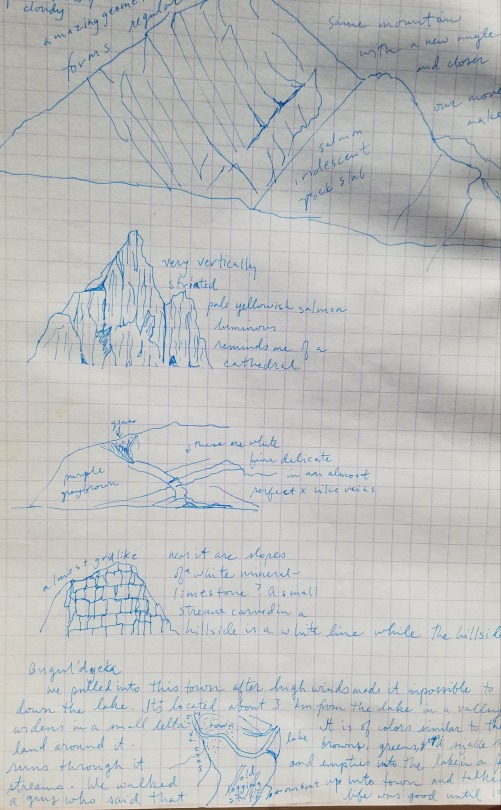

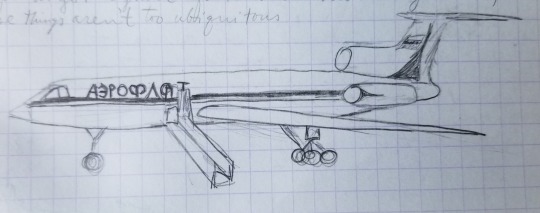

In early August 2001, I set down my bag in a simple dormitory in the village of Bol’shie Koty on the coast of Siberia’s Lake Baikal. “We each get a bed, cupboard, and closet space, and there’s a cool Russian stove. Our room overlooks the lake!” I enthused in my journal. Bol’shie Koty, whose 150 summer residents dwindle to only 80 in the deep Siberian winter, is, like many communities along the nearly 400-mile-long lake, accessible only by boat. The crescent-shaped lake is the world’s deepest (over a mile), the world’s oldest (at least 25 million years), and holds the most water of any lake (around 22% of the planet’s fresh surface water). Unique as well as superlative, Baikal hosts hundreds, if not thousands of animal species found nowhere else on earth, including sponges, fish, amphipods, and a freshwater seal. In remote southern Siberia, its watershed drains vast expanses of Mongolian steppe and Russian taiga, and the lake holds a somewhat mythical place in Russian culture. As part of the inaugural expedition of the Wellesley-Baikal program, which paired a spring course on Baikal history, literature, and ecology with summer study at the edge of the lake, I had rejoined my classmates after graduating from Wellesley and spending a summer in my home state of Vermont.

Over three weeks we explored the lake and its surrounding towns and forests, taking water samples and plant inventories and meeting local scientists, artists, land managers and even a shaman with a double thumbnail. On that gravelly shoreline, while also at the figurative shore where college meets adulthood, I was enchanted by the ways this place burst with both novelty and familiarity, and I immersed myself in observation to make connections between them.

On our misty boat ride to Bol’shie Koty, I saw eerie expanses of ghostly, bare tree trunks near the head of the Angara River, the bare, pointy stems resulting from an intense local outbreak of Siberian silk moth caterpillars. I was fresh from a field technician job counting invasive insects and inventorying disease in white pine stands for the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation, and diligently took photos for my boss back home.

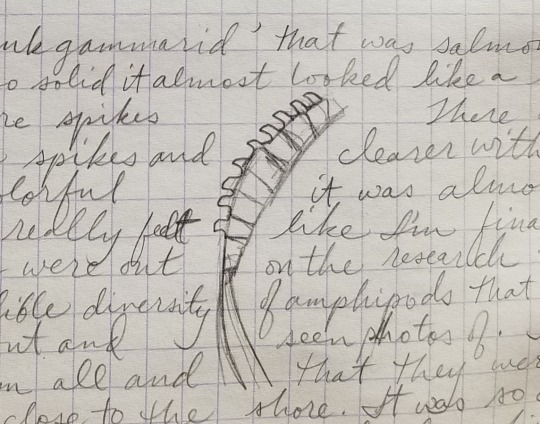

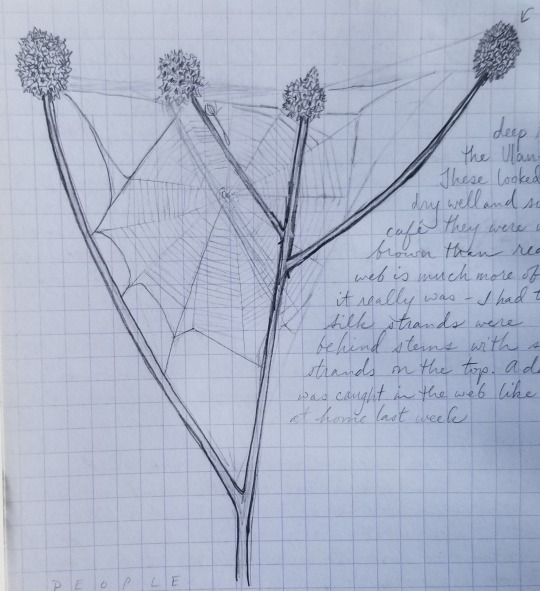

A few days after, I observed a female Siberian silk moth, “a beautiful creamy shimmery color with delicate folds,” alight on our boat in the lake, whose water looked “almost glacial in its deep blue green, slightly milky texture.” As I watched from where my classmates and I were taking samples, “one moth took off from our boat and flew valiantly toward shore, only to come closer and closer to the water until finally landing, becoming a creamy speck on the blue-green Baikal waters.” Later, I felt an odd surge of recognition - as well as horror - when one of us turned back a bedspread (“of a smooth cotton and muted brown/blue/purple/pale pink weave”) to find the grayish, fibrous lump of a silk moth cocoon. The caterpillars of Dendrolimus superans sibiricus defoliate Siberia’s characteristic coniferous forests, devouring needles of tamarack, pine, spruce, and fir.

Twenty years later, I’m back in Vermont, reading these somewhat overwrought - and repetitive! - words of my younger self while the larvae of Lymantria dispar (their common name, ‘gypsy moth’, is a derogatory ethnic slur) devastate trees around me during one of the worst outbreaks in Vermont in 30 years. Lymantria dispar larvae, like their distant Siberian cousins, feed on trees that distinguish Vermont’s forested landscape, though they defoliate oaks and other hardwood trees rather than the needle-leaved conifers that the Siberian caterpillars eat. I work as an ecologist and spend much of my time on projects that protect another huge lake, Lake Champlain, and its watersheds. I still love Russian literature, saunas, and dill, my appreciation for all of which sharpened during my time at Baikal. The world changed forever just three weeks after we returned from the far side of it that year. Yet in my own life, throughlines from those days along the crumbling shoreline continue to surface and reverberate in the present. Like the fine threads of a Siberian silk moth cocoon, these connect my past and present selves, shaping and in turn being shaped by perspectives and decisions that continue to unfold.

I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, but on rereading my excruciatingly detailed journal, I can see that this trip to Russia was the first time that I, at age 21, saw myself as a witness to and participant in the churning path of history, rather than merely a visitor to museums and ruins clearly separating past and present. Opposing truths can exist at the same time, the past continually bumps up against the present, and these moments and impressions form part of an unfolding and messy whole.

I marveled at juxtapositions. The beauty of the silk moths and the devastation of the forests in their wake. Wild-looking river deltas along the lake, thick with larch and cobble, that were in fact just decades out from the ecological and human devastation of slave-powered gold mining and deforestation. The expanse of lake viewed from an old rayon factory in Baikalsk, where I pondered a failed Soviet scheme to make airplane tires from wood pulp. A wolf wandered the shoreline and lynx pelts adorned the walls of a village home. Cows wandered the lanes and wooded margins of Bol’shie Koty, while rough fences kept livestock out of yards instead of in pastures, where they would have been in my familiar Vermont. Yet this surprising settlement pattern recalled early New England villages modeled after those in England, where overgrazing of common areas inspired the ecological and economic concept of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ in the mid-nineteenth century.

In Russia I saw academic concepts like this embodied in the land and lives around me, and the contrasts activated my thinking. Primed by the wide-ranging spring course with Tom Hodge and Marianne Moore, big thinkers with endlessly curious minds, I filled my journal with lists of plants, records of weather, notes from lectures and questions to consider.

One day our group got to witness the value of a long-term journal first hand. Talking with biologist Lyubov Izmesteva, in her dusty lab, we learned that her grandfather, Mikhail Kozhov, had begun recording ecological data on the lake in 1945, offshore from Bol’shie Koty. He passed the pen to his daughter and now granddaughter, and their collective decades of observation yielded a unique record of the lake’s health. Marianne Moore recognized the value of this careful record in 2001 and has shared it more broadly in the years since that trip. Reaching through and beyond the Soviet era, this family project is now helping the rest of the world understand how climate change is impacting Baikal.

Though I lacked a deep grounding in Russian political history, I felt a momentum in Russia, which seemed like it was still actively turning a corner from the drudgery and oppression of the Soviet era toward the complexities of democracy and capitalism. I knew the forested hills, river valleys, and watery depths around me held painful histories, like the cut-short lives of “uncounted, unregistered hundreds [of political hostages], unidentified even by a roll call” deliberately drowned in Baikal around 1920 as part of Russia’s post-revolutionary, pre-Stalinist horrors, and described by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago. In Moscow in 2001, I snapped a photo of a billboard advertising chewing gum, looming over a Soviet-era statue. The frivolity of the gum, its promise of a tiny personal diversion, seemed to contrast in a fascinating way with the stern Communist officer on his horse, frozen in metal.

In Moscow, I wrote, “Miles & miles from the city center are 6-lane streets, long apartment buildings, stores (many for furniture/home furnishings), people strolling, hurrying or waiting, painting, digging, talking, rolling out sod, carrying wallpaper, buying clothes, selling watermelons, riding bikes, doing exercises, kissing”. The pendulum seemed to be swinging toward growth and expansion. Yet other pieces just hadn’t caught up yet. I remember a car pulling another car on a busy city street with only a thick piece of rough twine, goldenrods and tall grasses adding a surprising wildness to the edges of city sidewalks, the shopkeeper in Bol’shie Koty calculating change with an abacus. I observed these dynamics with curiosity and delight.

In 2021, Baikal is an Instagram backdrop and Russia, presided over by a former KGB officer, a shaky mix of democracy and authoritarianism. I haven’t been back, but I wonder if the residents of that busy Moscow street still feel the forward-looking momentum I observed. Are they still carrying wallpaper and rolling out sod, shaping their spaces? As influencers filter images for fantastic effect and shadows of the Soviet era continue to loom, I can’t find the photos I took with film on that trip, or the paper (the last of my college career) that I wrote by hand on the porch at Bol’shie Koty. I still keep methodical notes about land for my job, but my personal journal these days contains mostly scattered thoughts on parenting, relationships, and career, quotes from podcasts, and conceptual brainstorms. I write in it to get ideas out of my head and process the complex dynamics of life, not to record anything for posterity. But in reflecting on Baikal two decades later, I realize my younger self gave me a gift in the form of her obsessively detailed notebook. She helped me decipher the throughlines that connect me to her, through a trip we both took to the other side of the world. My work now is to figure out how to pay this gift forward, to whatever selves come next.