#yuri kochiyama

I don’t want to mythologize or co-opt the memory of someone I admired so much, and I want to be especially cautious as I didn’t meet up with her much in person or get a chance to work with her often. But I felt compelled to share this nonetheless. One of the only times I’ve ever been speechless in my adult life was when I met Yuri. From what I recall, it’s because I agreed to be a part of an awareness-raising event for Viet Mike Ngo and Eddy Zheng, two inmates trying to start an Asian American studies program in prison. And at the same time, students at Berkeley were trying to raise awareness about deportations. Yuri was involved in both causes, no doubt many more, and activist Anmol Chaddha asked me if I would like to meet her. What do you say to her? She had done so much through history, for so many different communities and people, was inspiring countless young Asian Americans and other people. And yet, she never projected a demand for respect or to be deified. She was sincere, down to earth, fierce, smart, humble, inquisitive. She had political stickers all over her walker. Pictures of loved ones and I seem to recall, Hello Kitty, all over her walls. I wanted to learn all I could about her but instead found myself answering her questions about me as she jotted down notes in various notebooks with different colored pens. Anmol gave her a ride to a poetry reading I did on his motorbike. I was an even shittier poet back then, yet she was gracious and kind about my work. I didn’t get to hang out with her much or work with her much. But she did so much in her long life that inspired me. I feel like a failure all the time. All the time. Yuri’s great gift to us was to show by example that through all the important work she did, she remained a supportive, intelligent, warm and generous human being. Activists don’t have to be cold, strident, or stoic. Activists are human beings. They are not hero figures but members of the communities that they fight for. There are not words enough to thank her for that. My heart goes out to her family and the members of the community she worked with most closest. May she rest. And may the rest of us work.

Bao Phi is a poet & activist.

The Day I Read Aloud to Yuri Kochiyama

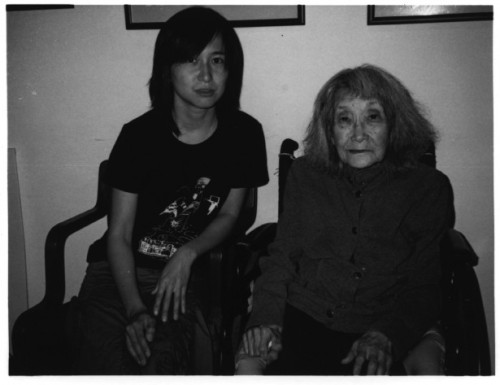

I didn’t meet Yuri Kochiyama until three years ago. By then, she was a few weeks short of her 90th birthday, living in an assisted living facility and no longer making public appearances. I was lucky. This summer, the renowned Japanese-American human rights activist passed away on June 1 at the age of 93.

For more than a decade before I ever shook her hand, Yuri Kochiyama had a huge influence on me. During my early years, as I tried to figure out my place in the prison justice and abolitionist movements of New York City, I was often the only Asian in the room. I didn’t know any other Asian involved in anti-prison organizing nor, did it seem, did any of the black, brown or white people with whom I connected. Sometimes, it felt like people were wondering why I was trying to be involved with anti-prison organizing instead of, say, organizing against anti-Asian violence or for the rights of Chinatown restaurant workers. Others were more hostile. The decade had started with the shooting of a 15-year-old black girl by a 51-year-old Korean grocer and, several years later, distrust and hostilities had yet to heal. Feeling as if I were lumped into the same category as the trigger-happy grocer made me feel like an unwelcome intruder at more than a couple of events. But still, I persevered, seeking out people and groups that didn’t automatically make assumptions based on my ethnicity. In part, this was because of Yuri.

Yuri Kochiyama still lived in New York City in the 1990s. I didn’t know her, nor did I travel in any of the same circles, but I knew that she existed and was, at least in my (teenage) mind, somewhat of a legend. Here was an Asian-American woman who had been working for prison justice for longer than I’d been alive. People respected both her and the work that she’d been doing. While we never organized (or even were in the same room) together, I’m pretty sure no one gave her a side-eye glance as if to silently ask, What is she doing here? This was Yuri Kochiyama, the woman who had lived through a Japanese internment camp during World War II, been a part of Malcolm X’s burgeoning Organization of Afro-American Unity and cradled him in her lap as he lay dying on the floor of the Audubon Ballroom. In addition to all that political activity, I also knew she had children and had raised them all to be political people as well. (I wouldn’t learn the magnitude of this until years later, when I read her memoir.)

So, even though I had never met her, I was inspired by her example.

In 1998, there was a march in Washington, D.C., demanding freedom for all political prisoners and prisoners of war in the United States. A bus of Asian-American activists supporting political prisoners was organized to leave from New York City. While the 4 a.m. sky was still dark, I boarded that bus with dozens of other Asian-American activists, including Yuri Kochiyama. That day, I was too shy to approach her, or to even talk to anyone I didn’t know, but it was obvious how respected and loved she was.

Hours later, we piled off the bus under a very sunny D.C. sky. As the 77-year-old Yuri slowly walked towards the action, people approached her, offering her wide smiles, adulation and teddy bears. (Over 10 years later, I learned that Yuri was known for her collection of K-bears, short for Kochiyama bears, that began as her children grew up and left home in the 1970s.) She accepted them graciously and continued to make her way towards the march.

That was my almost-encounter with Yuri Kochiyama. It was over a decade before I saw Yuri again. In those in-between years, I met other Asian Americans who were involved either in social justice organizing that sometimes intersected with anti-prison work or who were deeply involved in prison justice work. I also felt less hostility (or maybe I just grew a thicker skin) when I was the only Asian face in the room.

Fast forward to 2011. By then, I’d become a mother, become obsessed with finding the hidden histories (or herstories) of resistance and organizing in women’s prisons, and graduated college (in that order). I’d taken some of those hidden herstories I had uncovered and turned them into a book, then I’d gone on what I jokingly referred to as the Never-ending Book Tour. Although my book had been published in 2009, I was still on the Never-ending Tour two years later when I was in the Bay Area talking about women’s incarceration — specifically women imprisoned for self-defense and the movements that emerged to defend them. I also learned that my Never-ending Book Tour and other publicity efforts had led to my book being sold out. My publisher asked if I would do a second edition, which required new material.

In between book-related events, I made plans with a friend from the 1990s. He had been one of the Asian-American activists who had organized with Yuri and her husband, Bill, when they had lived in New York City. After moving to the Bay Area, he became the person who took on the responsibility of driving Yuri from her assisted living facility to wherever she needed to go. “Would you like to have dinner with Yuri Kochiyama?” he asked as we tried to make plans.

Would I? Really?

Even as an adult, I still get tongue-tied when in the presence of people who are considered movement superstars and, in my mind, Yuri Kochiyama was a huge movement superstar. I wasn’t sure if I would actually think of something to say to her, but I wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity to sit down to dinner with her. So off I went, with a copy of my book under my arm as a present.

We drove to her assisted living facility. Many of the residents recognized my friend from his frequent visits and greeted him by name as we walked down the hall to the elevator leading us to Yuri’s room. In my excitement at meeting the famous Yuri Kochiyama, I didn’t pay much attention to my surroundings.

Then we were out of the elevator and in her room. My friend introduced us, and she immediately welcomed me as if I were the celebrity. If she had no idea who I was, she definitely didn’t let on. Perhaps she was used to meeting young(er) Asian-American activists who were in awe of her. Perhaps she was used to putting these awe-struck fans at ease. Instead of waiting for me to stumble my way through starting a conversation, Yuri immediately began to ask me questions. Our entire conversation was filled with talk about women in prison, questions about why I was in the Bay Area, and a discussion of the piece I had written about women incarcerated for self-defense in the 1970s. She was also excited to know that we had other mutual friends in common from the long years of working around prison issues.

When we arrived at her daughter’s house, my friend suggested that I read parts of my book to Yuri. Although Yuri had been working around prison issues since before I was born, she was still horrified by the conditions I described, exclaiming, “Those poor women!” or “How terrible!” Sometimes, she looked as if she would cry at the litany of abuses and injustices I was reading out loud to her. I felt terrible that my book was depressing her. Somewhere between her second and the 20th exclamation, I decided that my second edition needed a chapter dedicated to stories of resistance, a section that could serve as a good read-aloud portion and leave the reader (or listener) with a sense of hope rather than sadness and futility.

Even before I spent that early evening reading aloud to Yuri Kochiyama, I knew that I wanted to write about resistance and organizing against horrific prison conditions. But the experience of reading to her — and inwardly cringing that my book was causing her distress rather than offering hope — strengthened my determination to seek and write about histories and herstories of prison resistance and organizing. The following year, the second edition of my book came out, including that chapter inspired by Yuri. Now, three years later, I write weekly pieces about resistance and organizing and, motivated by that evening, I continue to seek out stories that inspire and rouse us to action.

Victoria Law is a freelance writer, analog photographer, and parent. She is the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women andco-editor of Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind: Concrete Ways to Support Families in Social Justice Movements & Communities.

This post originally appeared in Waging Nonviolence.

Post link

Yuri was here

but

nothing

marks her birth

no nation

honors her death

so they made their own

testimony

of the life lived

the generations rebirthed

the children raised

the voices spurred

the borders crossed

the liberation sought

the evidence that she lived large

to scream that she stayed true

to show that she moved us forward

because it pains to see

our giant

leave without a trace

ignored or forgotten by most

but

cherished by those

who keep on

keepin’ on

Keepin’ the struggle alive

even when they mourn

when they decided

to gather memories

to commemorate her life

to celebrate her fight

on their own

they did just what

Yuri would do

if she were still here

Rest easy, Mrs. Kochiyama.

Jason Fong is a high school student at Redondo Union High School interested in Asian American issues.

I discovered Yuri and the inspiring Asian American movement activists like her at a time when I felt my identity didn’t matter, when it was ridiculed and I didn’t understand why. Now I do and I couldn’t understand why a dumb reason like the way I looked made me a victim. Like so many others like her, she taught me I’m not a victim and my identity meant something. So, I make this heartfelt declaration: please don’t let her memory, or any of the other Asian American movement leaders, fade away into nothingness.

Ralph Le

Yuri Kochiyama’s life and legacy is a reminder to Asian Americans and to all those who believe in social justice, of a basic value: to show up whenever and wherever injustice occurs and to engage in acts of resistance and solidarity. She did just that throughout her life. I remember how she became a strong voice to highlight the experiences of South Asians, Muslims, Arabs and Sikhs who faced discrimination in the aftermath of 9/11. Film director Jason DaSilva captured Kochiyama relating the post 9/11 dragnet of detentions and deportations to the experiences of Japanese Americans – including her own – who were interned during World War II. It wasn’t surprising that Kochiyama would make these connections. She had been an ally in key moments of struggle before, whether it was supporting political prisoners, calling for the establishment of ethnic studies programs, allying with the Black Power movement, or demanding Puerto Rican sovereignty.

Deepa Iyer is the former director of South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) and a writer and activist.

Yuri was one of the first activist Asian Americans I met as a college student in 1970. I had the privilege and honor of working with her to develop and organize Asian American resistance to the war in Vietnam, we marched together in Washington and NYC. She was an inspiration to many of us in rediscovering the hidden history of political and social struggle of Asian America. Through many of the dark early days her constant strength, wisdom and compassion helped me keep my own. Because she stayed the course in a lifelong crusade for human rights and dignity I was able to make and maintain my modest contribution in the same crusade.

Thank you, Yuri for being there for me, for us. You will be missed but never forgotten.

Johann Lee

This past spring, I wrote about Yuri Kochiyama for my senior honors thesis through the American Studies department at the University of California, Berkeley. I decided to write about the political activism of Yuri Kochiyama as an effort to challenge the Black-White racial paradigm that pervades the American mentality. I believe that by discussing stories of solidarity among ethnic minorities, we begin to understand the power of cross-racial collaboration and resist the racial categorization and separation enforced by white supremacy. Although I never met Yuri, I felt inspired and encouraged as I listened to interviews, watched documentaries, and read countless accounts of her brave, passionate work with underrepresented communities of color throughout her life. For this blog entry, I would like to share a portion of my thesis, which articulates her passion, hard work, and dedication to her community and the Black liberation movement:

“In the heat of the nationwide turn towards revolutionary politics and radical activism, Yuri Kochiyama developed her role as a “centerwoman,” an activist who is not a highly visible traditional leader like a spokeswoman, but nonetheless an important leader doing necessary “behind-the-scenes” work and providing stability to a social movement. A centerwoman directs her energy and passion for social change towards bringing people together, creating social awareness through personal conversations, and transmitting information through wide social networks. Kochiyama was able to embrace her role as a centerwoman in the Black community by joining or becoming an ally of many newly founded Black liberation organizations. Malcolm X’s death was a tragedy and an immeasurable loss to humanity. People across the globe were angry, saddened, and devastated. However, Black activists were also inspired by his legacy and founded Black nationalist, liberationist groups such as the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S), and the Republic of New Africa (RNA). From her involvement with these organizations, Kochiyama was able to develop deeper and wider connections with more members of the Black struggle. Kochiyama, who knew countless people, from famous Black leaders to friends of friends, became the human equivalent of a social encyclopedia. One RNA activist recalled:

“Yuri used to waitress at Thomford’s. That became like our meeting place. Everybody would come in and talk to Yuri. So when you come in, Yuri would have the most recent information for you. If we wanted to set up a meeting, she would set it up. If you had a message for someone, you’d just leave it with Yuri She must have received fifteen, twenty messages a day.”

Kochiyama had a wide reputation for being reliable and active in the movement. Whether she was writing articles for movement publications, attending protests and demonstrations, or handing out leaflets for organizations, people knew they could depend on Kochiyama to acquire or disseminate important information. Kochiyama even held open houses on Friday and Saturday nights at her home where activists could congregate and discuss revolutionary ideas directly among themselves. Since the 1950’s, Kochiyama had always opened her home to friends and strangers alike who needed a place to stay. From famous activists like SNCC and BPP leader Stokely Carmichael, poet and BART/S founder Amiri Baraka, and OAAU leader Ella Collins, to small children, guests from different backgrounds and perspectives felt her hospitality, generosity, and kindness in her oftentimes crowded, but nonetheless welcoming home.[i]”

[i] Diane Fujino. “Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism.” In Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 300-304

Hannah Hohle is a recent graduate from the University of California Berkeley and is now pursuing her career as an educator through the Urban Teacher Center in Washington, DC.

I visited Yuri and Bill in 1992 in their apartment in Harlem. The sofa where we sat was covered with dozens of cute little stuffed bears. On the walls were plaques and thank you messages from the Black community, at least one of them mentioning Malcolm X. I was there to learn about their history and perspectives on Asian American movement organizing. Years later I saw her give talks in different places and paying so much attention to everyone who approached her. She would ask for your name and record it in her little book, and then ask you all kinds of things about what you thought as if she were really learning from you. She was kind and strong and committed: one of a kind woman.

Karin Aguilar-San Juan is the editor of The State of Asian America: Activism & Resistance in the 1990s, published by South End Press

We first met Yuri and her family on New Year’s eve, December 31, 1964 when we were brought to a party at her home. My first recollection of her was how warm and welcoming she was, as were Bill and her children. I had also met Malcolm X and went to several of his smaller meetings and was at the large meeting the week before he was assassinated. I have often regretted not being there, but as I get older, I think it was probably for the best. The picture of Yuri cradling Malcolm’s head in her lap is one that will never be forgotten. Yuri came to The Free University and took courses with my husband, Charles. Charles and I had met on the 1964 trip to Cuba, and the Free Universiity was started by some of the students on that trip. Through the years we spent good times at Yuri’s home. She and Bill came to our wedding. She was one of the most courageous people I had ever met. She never stopped speaking truth to power. She fought for social justice and against racism all of her life. All the time she remained positive and cheerful, even at the funeral of her son, where she was so glad to see old friends. She is an inspiration to generations. In 2003 I was at the Sundance Film Festival and happened to see a documentary about her. I hope that documentry can be re released and shown where many can see it. Her passing is a loss to the world.

Anne K. Johnson

Yuri & William’s son, Billy was a civil rights worker in Mississippi in the 1960’s, as was I. Yuri and my father became friends as part of a grouping of parents of civil rights workers. And that’s how I met Yuri.

Yuri was totally dedicated to ending class exploitation, and, as well, used her experience with internment to fight every battle she could to fight national and racial oppression. She was gentle and yet a warrior, an intellectual and a student.

I chaired the New Jewish Agenda in the late 1980’s/early 1990’s. Yuri was proud of our support of justice for the Palestinian people…I loved Yuri. Honor to her memory, and power to the people.

Ira Grupper, Louisville, Kentucky

Nobuko,

From your last discussion concerning your visit to Yuri I yearned for her to be free, something that we do not like to say to each other. But most of my life Yuri’s spirit has been a comforting factor in all matters to our lives in struggle. A true ally and sister, friend and comforter. The last stages of her mental capacity must have been a task for her to comprehend. But knowing her and the many agendas she entertained, no thought, no statement, no directive did not have a precise objective. She was a person with a driving thirst to accomplish, and in her next life we better get on our p’s and q’s. She will be guiding our lazy spirits that yearn for rest. We must answer Yuri’s call and her example of a thriving spirit in all stages of existence.

She called my name and remembered my love for her. I am thankful. For me it’s an affirmation of the role she will play in my life at her next stage. I will always love her and remember her. Hear from you later Yuri. Enjoy the ride. I see your beautiful smile already.

Fate is a strange and twisted fiber that runs through the material of our lives. The inevitable meeting between Yuri and I was not by chance. The combined destiny of our lives, at least for me, was spiritual. We followed each other in a dynamic evolution. I benefited extraordinarily from sister Yuri’s sacrifices and audacity in the struggle.

She became a bridge to her world that I did not know. I began to see through her eyes, meeting brothers and sisters of I Wor Kuen, discovering acupuncture from her introduction. And she followed me to places, unbeknownst to my then young mind, in search for the truth. As part of the Republic of New Africa, we went together to Mount Bayou Mississippi to El Malik. She followed to help me watch my steps, never untangling or disloyal to our collective fate.

I’m not missing you Yuri, for you are within me. Your life has set a standard with which solidarity is built. There are very few in the world that can compare a lifestyle I committed myself to over these years to give honor to your mentorship. I’m so thankful for your example. Much of what our struggle has accomplished, you have been a driving force. I am so thankful.

I take the prerogative to thank you for the many who are waiting for you in the universe, and the many who are unaware of your transition. We love you so very dearly. I will continue to follow your example, and spread that special love for life and justice all over the world.

It is said that still waters run deep. But your love, Yuri, was never still, yet very deep. Troubled waters was when you shined and made love manifest. Such love is always in the eyes of the stars.

We will never forget WA 6-7412. Look out comrades out there in the universe! Here she comes!!! What a show. And to the Kochiyama family, lest we forget, love goes on forever because it is born in a part of us that cannot die. I love you all and thank you for being Yuri’s rock and inspiration.

Love you always.

Stiff resistance,

Your brother,

Dr. Mutulu Shakur.

P.S.

For all the P.O.W.’S, P.P.’S, exiles and martyrs.

Dr. Mutulu Shakur is a Black nationalist political prisoner and acupuncturist. He is currently incarcerated in the U.S. Penitentiary, Victorville, in Adelanto, CA.

A few years ago when I was first becoming politicized and scoping for the imprints of past leaders, there appeared Yuri. Of course it was by way of that famous black-and-white photo of young Yuri, speaking at an anti-war demonstration, and looking astoundingly fierce. Yuri resembled the worn photos I have of my own mother when she was in her mid 20s, and past my age only by a few years. What I felt when I saw this photo is how I imagine others felt when they saw Rosie the Riveter. To me, this photo was and is bravery and badassery personified.

While this image and Yuri’s lifelong resistance alongside Japanese American, Puerto Rican, and Black people urged me to practice outward acts of bravery of my own, learning about Yuri’s later life as a mother inspired me in a different way. In an interview, Yuri’s daughter recalled that their house “felt like it was a movement 24/7.” I imagined a home regularly warmed from stoves and body heat, with the lively din of chatter and laughter, and talk of the political and the everyday seamlessly intermixed.

Through her lifetime commitment of activism in myriad ways, Yuri taught me that activism isn’t confined to meeting rooms, or even on occupied streets. Yuri taught me that community work extends beyond tactics and strategy but is deeply interpersonal: it is how you treat youth and elders, how you relate to your neighbors, and with whom you choose to share your life, in love and in struggle. Yuri taught me that activism isn’t always bullhorns and storming the streets, it is humility, generosity, and fervent, unyielding compassion.

Minh Nguyen is an exhibit developer for the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle’s International District.

I met Yuri on the pilgrimage to Tule Lake internment camp immediately following the 9-11 attacks in NYC. The rise in overt racism against anyone who appeared to be Arab or Muslim made the pilgrimage especially powerful—it seemed as if history was on the verge of repeating. Tule Lake was the camp where Japanese American dissenters (“no-no boys”) were sent, and the dissent continued from inside, leading to the construction of a jail inside the camp. I sometimes accompanied Yuri as she used her wheelchair to visit different parts of the camp’s ruins, and she was always very kind, but also very fierce in her political commitments and support of young people taking up the fight for true freedom and justice. She was the first Asian American activist elder I met in the Bay Area, and thanks to her, I feel connected to an important lineage, one that continues to inspire me today—a touchstone I come back to often. I will always be grateful.

Kenji C. Liu is a poet, educator, and cultural worker.

Yuri showed me what it meant to be an Asian American radical when she came to my college campus back in the day when the Asian American movement was embryonic. The Kochiyamas welcomed young activists like me into their Harlem apartment and they were always warm, generous and gracious. She has embodied what it means to live for social justice and I will always keep her spirit and shining example close to my heart.

Helen Zia is a writer & activist.

Yuri was one of my New York O-nesans - “New York” meaning bad ass in 1970s SoCal-ese and “o-nesan” meaning beloved and respected older sister in Japanese. Along with Michi Weglyn, Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig and Kazu Iijima, these four Nisei women were unlike any I - and most West Coast Sansei - had ever known before and each of them in singular and collective ways became political, professional and personal Big Sisters not only to me but to my entire generation.

Michi was the elegant costume designer turned hardcore history detective whose book, Years of Infamy was the first historical investigation of the WWII incarceration written by one of its inmates. Aiko is the researcher who found smoking gun evidence that the U.S. government premeditatively suppressed, altered and destroyed critical documents regarding the mass incarceration. Kazu was, according to Yuri, “the most informative and compelling Asian American woman on the East Coast” and the one Yuri credits for bringing her into the Asian American movement. All of these extraordinary women, as it turns out, were blessed with exceptional husbands - Walter Weglyn, Jack Herzig, Tak Iijima and Bill Kochiyama - each of them also very special to me. In their exhaustive support of their wives, they were truly the men behind the women, enabling Michi, Aiko, Kazu and Yuri to do what they did, making this world a better place for generations to come.

I would venture that the majority of accolades and remembrances of Yuri will be on her vast political contributions as Asian Pacific America’s foremost heroine. As much as I look forward to reading them - and encourage everyone to put down their own memories and tributes - for once I may be among the one percent, of those remember Yuri, not as much for her political contributions as being a mere mortal who succeeded in living well - and a corny Nisei lady at that.

There are many personal stories that bubble up. Of her looking deep within me when we first met in 1972 looking for a glimmer of my mother who Yuri had known before the war and who had died soon after the war. Of when I took Yuri and my Auntie Ets to dinner and they carried on into the evening like two elderly Nisei ladies who hadn’t seen each other in years with nary a political phrase uttered. But I think people would get a kick out of knowing about Christmas Cheer, the annual newsletter Yuri and Bill published out of their tiny Harlem apartment with the forced labor of their kids: Billy, Audee, Aichi, Eddie, Jimmy and Tommy.

In conducting research for my upcoming book on the Asian American movement, I re-read the copies Yuri had sent to my mother’s family. As I emailed Audee, Eddie, Jimmy and Tommy, these Christmas Cheer newsletters reveal their famous parents in special ways that are often overshadowed by Yuri’s public and political persona.

Christmas Cheer was one hella production considering it was produced pre-technology-as-we-know-it and must have taken months to write and assemble since it was really a national newspaper in disguise with a circulation of hundreds of people. (In response to my email, Jimmy joked that Yuri and Bill must have had six kids in order to handle the production demands.) Each issue listed every marriage and baby born during that year from NY to Hawai’i as well as articles written by each of the kids. Many of the early issues had themes that were carried out in the design and writing. For example, the theme of the 1959 issue was popular magazines with column titles such as “Children’s Digest” for the kid’s articles, “Parents” for the baby column, and “Modern Romances” for the weddings - with each headline lettered in their corresponding magazine’s logo.

They reveal how wonderfully downhome and downright corny Yuri and Bill were. Or rather, korny. They had a penchant for substituting “k’s” for “c’s” - kind of like we did later with Amerika but in 1951 it was phrases like “Kochiyama Klan Kapers to Kinfolk in Kalifnorniya.” When my daughter Thai Binh was little, she used to say how corny adults are. Well, this was pure corn. We are much too cool to be corny, which is really too bad.

Most notably, Yuri and Bill’s connection to all of humanity is apparent through the issues from the first to the last. Mostly, of course, it was everyday family and folks they cherished and reported on as if they celebrities. Each issue listed some hundred people they saw, corresponded with or just plain thought of through the year. And sometimes they mingled with for-real celebrities who I’m sure they treated like everyday folk. Besides the famous visit from Malcolm X in 1964, the 1958 issue reports that they met First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Little Rock NAACP leader Daisy Bates and renowned Zen Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki. I’m sure this trio never appeared in the same article together again. As so many have testified to Yuri’s radical politics and passion for justice, and so many of us remember Bill’s quiet strength and resolve, these Christmas Cheers are testimony to their deep and oceanic love of ordinary life and just plain folk.

One caveat: as much as Yuri was salt-of-the-earth, she was also star-struck - for example, running after Japanese actress Miyoshi Umeki for her autograph with three kids on each side of her holding on for dear life. And yet this is precisely what made Yuri the extraordinary person she was: her capability to be a political powerhouse as well as a corny Nisei lady. She treated every student and admirer in the same manner she treated the biggest and baddest revolutionary - perhaps because she was herself a unity of what others might think of as contradictory. By her words and deeds, she dared us to struggle. But by her example, she also tells us to have a life - have children, run after autographs, be corny, savor everything.

Horace Mann once said, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” Yuri was not ashamed to die. As much as this is a tribute to Yuri, I’d like to end with a note of acknowledgement and thanks to Yuri’s surviving children Audee, Eddie, Jimmy and Tommy for sharing their mother with too many people for all these many years. Especially when they were young and came home to find their home a youth hostel or Grand Central Station. And especially now when what would ordinarily be a private grieving must be extraordinarily shared with thousands.

Karen Ishizuka’s latest book is on the making of Asian America to be published by Verso Press in 2015.

I’ve never had the honor of meeting Yuri Kochiyama, but her power, her passion, her presence has continually lingered in the atmosphere, like a spark in the ether. The iconic image of Yuri speaking with ferocity at a 1968 anti-war demonstration is branded into my brain, and no doubt countless others — young and old, Asian American and non — who, like me, hope to manifest even a small part of her fearless life and vision. This image of Yuri is audacious, it is righteous, and it still quickens my blood every time I see it. It shows someone who does not look like what we’ve been conditioned to believe a hero can look like in America, but who was nevertheless propelled by the courage of conviction, who boldly lived her values, and who modeled what justice can look like when we build together. I see a woman warrior, and it is in Yuri’s legacy that I can imagine the promise and potential of our beloved society. Thank you for all you’ve given us.

Cynthia Brothers is Managing Blog Editor of Hyphen Magazine and a consultant to organizations that have included Four Freedoms Fund, 18MillionRising, and Culture/Strike.

I had this crazy dream last night.

Yuri Kochiyama and Amiri Baraka were up in heaven…playing Ronald Reagan and Strom Thurmond in a game of 2-on-2 basketball.

The stakes? Dismantling the segregated institutions of heaven. Why all the clouds gotta be white? Baraka asks. Why all the white angels get the nice harps, and we get these hand-me-down purgatory ukeleles?

The score is tied. 14-14. Next basket wins.

Yuri looks at Baraka like, Don’t worry, my dude. I got this.

She dribbles the ball slowly up the cloudy court. Then, quick as lightning, Yuri puts the ball between her legs, flies over Reagan, karate chops Strom Thurmond in the face with one hand, wipes ups his tears with her other hand, does a triple somersault in the air, and dunks the ball so hard, the basket explodes - BOOM! - like the echo of a Harlem gunshot.

Baraka looks over at Yuri, grinning like a well-fed cat. That’s what I’m talking about, girl. Wish the Knicks knew how to play like that.

From the sideline, Maya Angelou whistles her approval. Phenomenal, she says. Simply phenomenal.

Reagan scrapes himself off the floor, tries to regain his composure. Whatever. Y’all wanna run again?

Yuri looks down to Earth. At her people, her nation of struggle and pain and possibility, still fighting the fight she fought for damn near a century. She just got here, to this city in the stars. Doesn’t she deserve some time to rest her feet?

Maybe later, but right now, she’s staring down the man who drove half her closest friends to jail or drugs or an early grave. And up here, he doesn’t have Secret Service to defend him in the paint. Yuri is more than happy to take it right to him and his buddy Strom. Shit, she could do this forever.

Winner takes ball, she says. Let’s go, Ronnie. Game on.

Josh Healey is a writer, performer, and creative activist. He is currently spreading political art and subversive humor with the good folks at Movement Generation. He lives in Oakland and plays a mean game of spades.

When I introduced Buraku brethren to her, Yuri sat up in indignation, made a fist and thumped on her thigh and said “for decades I have met Japanese activists come through Harlem and read about Japan but I never ever heard anything about the injustice of the Buraku people. As someone of Japanese ancestry, I am enraged, and so ashamed of the Japanese government!” She turned to me and said thank you for bringing them over, she could not imagine not knowing about this reality. I will remember that moment so vividly for the rest of my life. For once we were not a threat to a Japanese in that moment, but to the injustice which we stood. She then went onto learning about Kazuo Ishikawa, Buraku victim of wrongful incarceration, the famed Japanese taiko drum making being a Buraku art, the many illiterate Japanese denied education as Buraku, and the ongoing hidden apartheid and discrimination condoned in society as a means of ‘keeping Japanese blood pure.’ I have had the privilege of delivering your solidarity messages through Buraku, as well as our Zainichi and Okinawan villages and know firsthand, you remain a steadfast icon of solidarity and friendship above and beyond the reach of Japanese imperial system (Tennousei) across the vast waters. I can almost hear the rejoicing of your coming by the countless 'comfort women’ grandmas you spoke for, joined by brothers and sisters from Puerto Rico to San Quentin… We will never forget your stories and your tenacity and commitment to justice and dignity of all people. Thank you ゆり。

Miho Kim is a Bay-Area-based Trans-Pacific Zainichi Corean activist. Former Executive Director, DataCenter for Research Justice and co-founder, Eclipse Rising and Japan Multicultural Relief Fund (JMRF)

Yuri spent a good portion of her young adult life in a concentration camp of Japanese people in the US. From this foundational experience emerged a solid revolutionary force of nature. While we all remember her work with Malcolm X, she should be remembered also (and perhaps, more visibly) as a participant in actions such as taking over the Statue of Liberty with Puerto Rican independence activists. Her commitment to active participation in anti-imperialist and national liberation movements the world over was her life’s work - and it went on for decades after Malcolm X’s murder.

She was pivotal in the movements to free Mumia Abu Jamal and other political prisoners and end nuclear proliferation. She has been a consistent friend of the oppressed peoples of the world. She has prominently defended the revolutions in the Philippines, Peru, and elsewhere. Despite the very small active base of Japanese-Americans involved in struggle for national liberation, Yuri is an important figure and worker for liberation precisely because while jettisoned by the persecution and internment of her own family and community, she actively took up the struggle of the world’s majority. Her relationship to national liberation organizations fighting for self-determination, as a working active figure, sets her as a giant on whose shoulders we all stand.

Evaristo Marrero, maosoleum an organ of the Liaison Committee for a New Communist Party

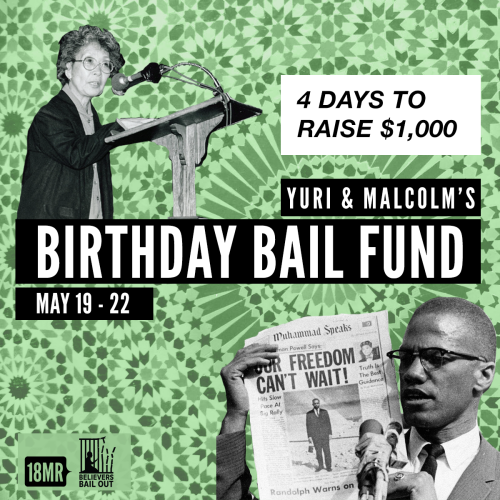

No one belongs in a cage. This year, in honor of Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X’s joint birthday on May 19, we’re raising $1,000 for a bail fund. $1000 is the amount it takes to free one incarcerated Muslim who is currently locked up in a jail or ICE detention center.

This fundraiser is in partnership with Believers Bail Out, a Chicago-based national effort to bail out Muslims who are being held in jail prior to their right to a trial, or trapped in ICE custody. BBO is community-led and volunteer-run, predominantly by women of color. In the past two years, BBO has freed 38 Muslims from jails and immigration incarceration by paying their bail!

Help us free people from cages! Support our bail fund here.

Post link