#16th century

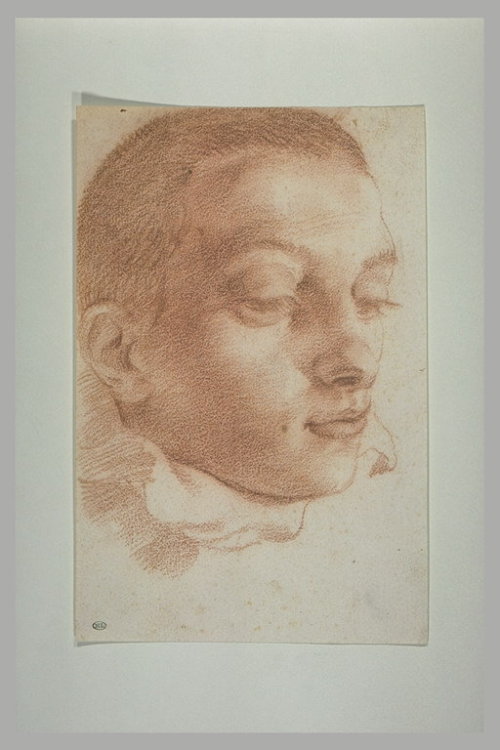

Annibale Carracci (1560–1609, (attribué à)

Tête de jeune homme, de trois quarts, les yeux baissés

Louvre

Post link

Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) - atelier de

Paysage avec un vase colossal examiné par un homme - Ici encore on peut évoquer une relation avec le parc Orsini à Bomarzo, où un vase colossal est encore visible.

Louvre

Post link

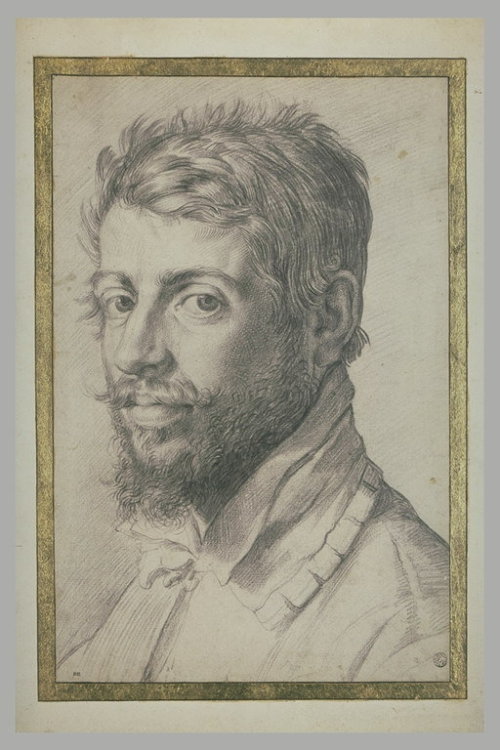

Annibal Carrache (1560-1609), cercle de Ecole bolonaise

Portrait d'homme de trois quarts (material black and white chalk on paper)

Louvre

Post link

Memento Mori watch owned by Mary, Queen of Scots. 16th century. Engraved along the base of the skull is a verse from Horace: “Pale death visits with impartial foot the cottages of the poor and the castles of the rich."

Post link

Daniel Mytens - Margaret Tudor, Queen consort of Scotland

circa 1620-1638

oil on canvas

The Royal Collection, Edinburgh

Post link

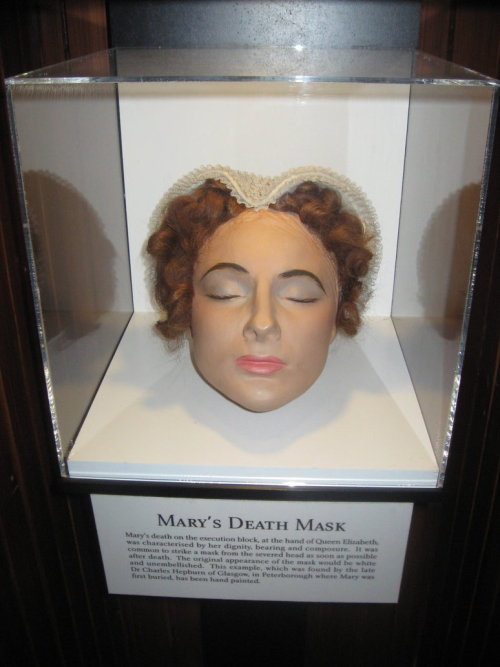

On February 8th 1587 Mary Queen of Scots was beheaded at Fotheringay Castle.

Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantome was a member of the French nobility who accompanied Mary during her internment. He provides us with a sympathetic account of Mary’s execution that begins with the arrival of a delegation from Queen Elizabeth announcing that the former Queen of the Scots is to be executed the next day:

“On February 7, 1587, the representatives of the English Queen, reached the Castle of Fotheringay, where the Queen of Scotland was confined at that time, between two and three o'clock in the afternoon. In the presence of her jailer, Paulet, they read their commission regarding the execution of the prisoner, and said that they would proceed with their task the next morning between seven and eight o'clock. The jailer was then ordered to have everything in readiness.

Without betraying any astonishment, the Queen thanked them for their good news, saying that nothing could be more welcome to her, since she longed for an end to her miseries, and had been prepared for death ever since she had been sent as a prisoner to England. However, she begged the envoys to give her a little time in which to make herself ready, make her will, and place her affairs in order. It was within their power and discretion to grant these requests. The Count of Shrewsbury replied rudely:

‘No, no, Madam you must die, you must die! Be ready between seven and eight in the morning. It cannot be delayed a moment beyond that time.’ ” It was that sudden, very little time for Mary to prepare, a brutal way to spend the last few hours on this earth……..Mary spent the rest of the day and the early hours of the next morning writing farewell letters to friends and relatives, saying goodbye to her ladies-in-waiting, and praying.

At 2 am on Wednesday 8 February 1587, Mary Queen of Scots picked up her pen for the last time. Her execution on the block at Fotheringhay Castle was a mere six hours away when she wrote this letter. It is addressed to Henri III of France, brother of her first husband. The letter was written in French, the following is a translation and is a fascinating insight into the mind of our Queen hours before her murder. Mary had only learnt her fate a few hours earlier.

Note, even though she had been forced to abdicate, and had been a prisoner of her cousin for 19 years, she still called herself, Queen of Scotland.

Queen of Scotland

8 Feb. 1587Sire, my brother-in-law, having by God’s will, for my sins I think, thrown myself into the power of the Queen my cousin, at whose hands I have suffered much for almost twenty years, I have finally been condemned to death by her and her Estates. I have asked for my papers, which they have taken away, in order that I might make my will, but I have been unable to recover anything of use to me, or even get leave either to make my will freely or to have my body conveyed after my death, as I would wish, to your kingdom where I had the honour to be queen, your sister and old ally.

Tonight, after dinner, I have been advised of my sentence: I am to be executed like a criminal at eight in the morning. I have not had time to give you a full account of everything that has happened, but if you will listen to my doctor and my other unfortunate servants, you will learn the truth, and how, thanks be to God, I scorn death and vow that I meet it innocent of any crime, even if I were their subject. The Catholic faith and the assertion of my God-given right to the English crown are the two issues on which I am condemned, and yet I am not allowed to say that it is for the Catholic religion that I die, but for fear of interference with theirs. The proof of this is that they have taken away my chaplain, and although he is in the building, I have not been able to get permission for him to come and hear my confession and give me the Last Sacrament, while they have been most insistent that I receive the consolation and instruction of their minister, brought here for that purpose. The bearer of this letter and his companions, most of them your subjects, will testify to my conduct at my last hour. It remains for me to beg Your Most Christian Majesty, my brother-in-law and old ally, who have always protested your love for me, to give proof now of your goodness on all these points: firstly by charity, in paying my unfortunate servants the wages due them - this is a burden on my conscience that only you can relieve further, by having prayers offered to God for a queen who has borne the title Most Christian, and who dies a Catholic, stripped of all her possessions. As for my son, I commend him to you in so far as he deserves, for I cannot answer for him. I have taken the liberty of sending you two precious stones, talismans against illness, trusting that you will enjoy good health and a long and happy life. Accept them from your loving sister-in-law, who, as she dies, bears witness of her warm feeling for you. Again I commend my servants to you. Give instructions, if it please you, that for my soul’s sake part of what you owe me should be paid, and that for the sake of Jesus Christ, to whom I shall pray for you tomorrow as I die, I be left enough to found a memorial mass and give the customary alms.

This Wednesday, two hours after midnight.

Your very loving and most true sister, Mary RTo the most Christian king, my brother-in-law and old ally.

We rejoin de Bourdeille’s account as Mary enters the room designated for her execution and is denied access to her priest:

“The scaffold had been erected in the middle of a large room. It measured twelve feet along each side and two feet in height, and was covered by a coarse cloth of linen.

The Queen entered the room full of grace and majesty, just as if she were coming to a ball. There was no change on her features as she entered.

Drawing up before the scaffold, she summoned her major-domo (steward) and said to him:

‘Please help me mount this. This is the last request I shall make of you.’

Then she repeated to him all that she had said to him in her room about what he should tell her son. Standing on the scaffold, she asked for her almoner, (chaplain) begging the officers present to allow him to come. But this was refused point-blank. The Count of Kent told her that he pitied her greatly to see her thus the victim of the superstition of past ages, advising her to carry the cross of Christ in her heart rather than in her hand. To this she replied that it would be difficult to hold a thing so lovely in her hand and not feel it thrill the heart, and that what became every Christian in the hour of death was to bear with him the true Symbol of Redemption.”

Standing on the scaffold, Mary angrily rejects her captors’ offer of a Protestant minister to give her comfort. She kneels while she begs that Queen Elizabeth spare her ladies-in-waiting and prays for the conversion of the Isle of Britain and Scotland to the Catholic Church:

“When this was over, she summoned her women to help her remove her black veil, her head-dress, and other ornaments. When the executioner attempted to do this, she cried out:

‘Nay, my good man, touch me not!’

But she could not prevent him from touching her, for when her dress was lowered as far as her waist; the scoundrel caught her roughly by the arm and pulled off her doublet. Her skirt was cut so low that her neck and throat, whiter than alabaster, were revealed. She concealed these as well as she could, saying that she was not used to disrobing in public, especially before so large an assemblage. There were about four or five hundred people present.

The executioner fell to his knees before her and implored her forgiveness. The Queen told him that she willingly forgave him and alI who were responsible for her death, as freely as she hoped her sins would be forgiven by God. Turning to the woman to whom she, had given her handkerchief, she asked for it.

She wore a golden crucifix, made out of the wood of the true cross, with a picture of Our Lord on it. She was about to give this to one of her women, but the executioner forbade it, even though Her Majesty had promised that the woman would give him thrice its value in money.

After kissing her women once more, she bade them go, with her blessing, as she made the sign of the cross over them. One of them was unable to keep from crying, so that the Queen had to impose silence upon her by saying she had promised that nothing of the kind would interfere with the business in hand. They were to stand back quietly, pray to God for her soul, and bear truthful testimony that she had died in the bosom of the Holy Catholic religion.

One of the women then tied the handkerchief over her eyes. The Queen quickly, and with great courage, knelt dawn, showing no signs of faltering. So great was her bravery that all present were moved, and there were few among them that could refrain from tears. In their hearts they condemned themselves far the injustice that was being done.

The executioner, or rather the minister of Satan, strove to kill not only her body but also her soul, and kept interrupting her prayers. The Queen repeated in Latin the Psalm beginning In te, Damine, speravi; nan canfundar in aeternum. When she was through she laid her head on the block, and as she repeated the prayer, the executioner struck her a great blow upon the neck, which was not, however, entirely severed. Then he struck twice more, since it was obvious that he wished to make the victim’s martyrdom all the more severe. It was not so much the suffering, but the cause, that made the martyr.

The executioner then picked up the severed head and, showing it to those present, cried out: 'God save Queen Elizabeth! May all the enemies of the true Evangel thus perish!’

Saying this, he stripped off the dead Queen’s head-dress, in order to show her hair, which was now white, and which she had been afraid to show to everyone when she was still alive, or to have properly dressed, as she did when her hair was fair and light.

It was not old age that had turned it white, for she was only thirty-five when this took place, and scarcely forty when she met her death, but the troubles, misfortunes, and sorrows which she had suffered, especially in her prison.”

The account of Pierre de Bourdeille was originally published in 1665 and republished many times thereafter.

To me her execution was one thing, the way she was treated in death another.

The Queen’s body was embalmed, her entrails secretly buried within the grounds, and she then lay in a lead coffin within Fotheringhay Castle for nearly six months! Queen Elizabeth at last ordered her burial, which was to be in Peterborough Cathedral, denying Mary’s request to be laid to rest in France next to her first husband, King François ll. The Burial Register at Peterbotough contains this entry for the year 1587:

The Queene of Scots was most sumptuously buried in ye Cathedral Church of Peterburgh the first day of August 1587 who was beheaded at Fotheringhay Castell the eight of February before.

The Queen’s body was exhumed 25 years later by her son James l and laid in an ornate marble tomb in Westminster Abbey next to her cousins Elizabeth l and Mary Tudor. What remained of the empty tomb in Peterborough Cathedral was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell’s forces in 1643 when they despoiled the building on their way to attack the Royalist garrison at Crowland.

Post link

✧ Mary always kept dogs, and when she was held a prisoner in England for nineteen years, the queen was allowed to keep her beloved companions with her. As reported by one of her jailors, she would sometimes spend hours talking to her lap dogs; about religion and her estranged son, James. It appears Mary favoured the Maltese and Terrier breeds, and whether it was a Skye Terrier or Scottish Terrier, that stayed by her side during her execution, it was nevertheless, a faithful friend.

Post link

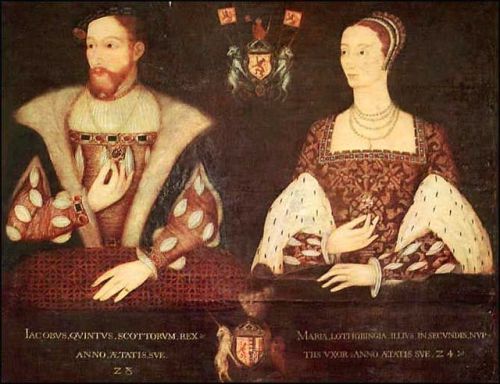

On November 22 1515 Mary of Guise was born.

After his first French wife (Madeleine of Valois) died, James V planned a second marriage to cement the renewed Auld Alliance. He chose Marie de Guise - a widow with two sons from a brief but happy marriage.

While James V was negotiating for Marie’s hand he had to contend with competition from his uncle, Henry VIII of England. Henry was looking for another wife – he had divorced his first wife Catherine of Aragon, beheaded his second wife Anne Boleyn, and his third wife, Jane Seymour, had died just after giving birth.

Henry’s record of failed marriages meant that Marie’s father refused him and accepted James. Marie de Guise was initially unwilling but relented when James wrote to her directly.

Marie and James had two sons who both died, and one daughter, Mary I (Mary Queen of Scots). Marie de Guise was appointed Regent in 1554, taking over from James Hamilton, 2nd Earl of Arran.

Marie de Guise was Catholic. The rise of the Scottish Protestants threatened her position. When she called on her family in France for help this was seen as proof that she was not loyal to Scotland. She was deposed as regent in 1559.

The first pic is a portrait attributed to Dutch painter Corneille de Lyon, when Marie was around 32, the second is Marie and her second husband, King James V of Scotland, this pic hangs in Falkland Palace, the third a carving by John Donaldson and part of the stunning Stirling Heads at the castle in the town.

More in depth details about Marie de Guise here http://www.maryqueenofscots.net/…/mary-marie-guise-queen-r…/

Post link

25 September 1615 ✧ The death of Lady Arbella Stuart

“Arbella’s life seemed to have ended not with a bang, but with a whimper—and that is no finish for a story. It is true she left not obvious legacy: in the most direct sense, her few goods were immediately seized on the privy council’s authority. In the broader sense, her contribution is an elusive matter. And yet, almost four hundred years after her death, she does not live in posterity. Several chains of action and event—genealogical, historical, ideological—make it hard to end her tale in 1615. They are tenuous, amorphous; so much so that to overemphasize any one is to perform the conjurer’s trick of misdirection. To proclaim that this, this, is why she mattered, is to evoke a strong aroma of sawn-up lady. But together the fragments of the kaleidoscope make Arbella Stuart a curiously ubiquitous ghost; one whose presence cannot easily be dismissed, thought she may haunt only the fringes of history.” – Sarah Gristwood, Arbella: England’s Lost Queen

Post link

ab. 1560 Giovanni Battista Moroni - Woman in a Red Dress

(Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden)

Post link

The Burial of Christ

Annibale Carracci (Italian; 1560–1609)

1595

Oil on copper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Post link