#academic librarians

Happy National Library Workers Day! May your break room snacks be plentiful and your library snakes scheduled and well supervised!

I’m posting this here as well as FB:

Friends, if you hear your library is going to open up even for curbside pickup, I’m asking you to publicly request details of how staff will be safe. Are there plexiglass shields? Ok, how high and where? PPE? What PPE exactly and is it being taken from medical professionals? How much do they have to reuse it? The books will be cleaned/quarantined? How long and with what? How are you going to keep staff safe from people who refuse to wear masks or distance? Who’s cleaning the bathrooms? What happens if a patrons spits or coughs on people? How are they protecting Asian-presenting staff from hate speech and acts of violence? If staff have to ride public transportation do they have a place to change when they get to work or do you provide masks to them before they get on the bus?

I know you miss the library but for every decent person who washes their hands and wears a mask there’s one who will tell me it’s a hoax and lick the checkout computer. I signed up to be a librarian, not a first responder.

If you’re reading this, download Libby or RB Digital or whatever your library uses and get new content that way, don’t fucking romanticize the library and put us at risk. We’re just people trying to keep our families safe.

“But restaurants/bars/grocery stores are allowed to be open or do pick up!”

Yes, and they don’t require you to return your used bags, dishes, and packages to be handed to the next person in line.

Many libraries serve as default day centers for homeless and others with nowhere else to go. People are also staring to go a little stir crazy after being stuck at home for so long, I get it. While loads of people are making the right choice and staying home if libraries open they will be full. This is a very rare case where librarians are shouting that our doors need to be/stay closed. Use ALL of the amazing digital services or phone services we offer, but STAY THE FUCK HOME.

Today’s post, entitled “Camilla Leach: A sophisticated spitfire (1835-1930)”, comes from Paula Seeger, Design Library, University of Oregon, with significant contributions from Ed Teague, Retired Director of Branch Libraries, University of Oregon. All photos are courtesy of University of Oregon Libraries.

Summary

Ultimately known for her role as the founding librarian-manager of the Design (formerly Architecture and Allied Arts) Library at the University of Oregon, Miss Camilla Leach left a legacy of caring for student success and ambition throughout her long career. Only in the last third of her life did she find a role in the library, with the majority of her time spent in the classroom or dormitory, supervising and guiding the lives of young adults, especially girls. Miss Leach constantly updated her position during a long career trajectory, never losing her love of the arts and French culture and design. She travelled to Paris in her 30s, was committed to the plight of French orphans during WWI, and translated Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students of the University of Oregon. This fascination with French culture and artistry bestowed an air of sophistication to Miss Leach. Combined with her “go-getter” determination that impressed the administration and faculty, Miss Leach’s keen observational skills and broad knowledge let her anticipate the needs and interests of her loyal colleagues and patrons. This unique mix allowed Miss Leach to win over those who doubted she could take an active role in organizing a new library and departmental administration office at the age of 79. Even though she “retired” twice from the libraries at the University, Miss Leach remained active in the community and social circles, giving talks on the relation of art to library work to civic groups into her 90s. Piecing together her history, as well as reflecting on her legacy, is a worthy exercise that re-emphasizes a lifelong commitment to arts education and wisdom born from the strength of longevity.

Background and Early Career

Miss Leach’s history has been difficult to completely trace. We assume certain facets of her life and try to fill the gaps within her story for which we do not yet have evidence, such as Miss Leach’s education and much of her early life. While we know she was born in Rochester, New York in 1835, and there are some accounts of her attending East Coast schools, we next find definitive mention of her in 1855. While still living at home in New York, her profession was listed as “teacher” at age 19 in the New York state census of 1855, indicating she began her teaching career early. Using broad searches of historical newspapers, we can see that she travelled south and west, taking a position at a teaching college in 1859. Her title was Governess and assistant teacher of the “English branches” at East Alabama Female College (also called “Tuskegee Female College” at its founding in 1854, later “Huntingdon College” after the institution moved to Montgomery). By 1865, she arrived in Chicago and was granted a teaching certificate to teach at a number of public schools including Skinner school and the main Chicago High School. It is during this time Miss Leach was elected to be “Professor of Rhetoric and English Literature” at the high school and a wage dispute was noted (1870):

Miss Camilla Leach was recently elected professor of English literature in the Chicago high school, but the board of education refuses to pay her over $1000 for work for which her male predecessor received $2,200.1

It is unknown whether this dispute led to her resignation, but shortly after, in 1871, Miss Leach applied for a passport to travel to Europe to study art and visited Paris in 1871-72, becoming well-versed in French art and architecture. After Europe, she returned to a position as a high school teacher in St. Louis in 1872-73, and was announced as a teacher at the Washington school for Minneapolis Public Schools in 1878. Another newspaper account in August 1878 mentioned that she was an art instructor in a Placerville, CA, ladies’ seminary and private school (TAE Academy). Having settled in Oakland, CA, from 1879-89, Miss Leach taught drawing and French at the Snell Seminary, a “boarding and day school for girls” that operated from 1878-1912. While at the Snell Seminary, Miss Leach perhaps learned more about opportunities that could be found in Oregon. During her tenure, one of the Seminary’s founders, Dr. Margaret Snell, began an affiliation with Oregon State University (then called the Corvallis College and the State Agricultural College of Oregon) through a Corvallis resident who happened to be staying in the Oakland area caring for an ailing relative. Dr. Snell went on to found the department of “Household Economy and Hygiene in the Far West,” the first in the western U.S. and went on to a great legacy at Oregon State.3

Perhaps also influenced by Dr. Snell’s continuing education in the East, Miss Leach attended Bryn Mawr with “Hearer” status in 1889-902 and it is assumed that this is where she completed her education about “library methods”. Returning to California, Miss Leach was introduced as Mistress of Roble Hall, a ladies’ dormitory at Stanford University in 1891, the first year Stanford started enrolling students. After administrative and facility restructuring, she was let go from Stanford in 1892, heading north to Portland, OR.

Miss Leach stayed five years in Portland working as a private tutor and head of a private school, perhaps of her own creation, within a wealthy businessman’s household. These many years spent as an educator, administrator, and overall caregiver of young student lives had now prepared Miss Leach for a more significant career transition as she was recruited by the University of Oregon in 1897 to become their first dual registrar-University librarian, beginning her new role in libraries. It is unknown what motivated this career change for Miss Leach at about age 60–or age 50: In subsequent census records Miss Leach somehow gets ten years younger.

University of Oregon Career

In 1897, the University of Oregon in Eugene recruited Miss Leach to be the school’s first registrar while also serving as the University’s librarian in a combined position. The dual job was split in 1899, when Miss Leach became “only” the University librarian and, later, the school’s first art librarian. She contributed to the school’s publications, offering a review of Bryn Mawr and several original pieces of poetry for the University’s yearbook and monthly journals. The University originally had a small library collection, based mainly upon generous donations from professors before state allocations were negotiated, and the collection was relocated several times before the first purpose-built library opened in 1906. In 1912, Miss Leach retired from her library position, but continued to teach in the art school as a drawing instructor and teacher of art history, which she continued throughout her next role. At the time of her “retirement” as a reference librarian from the main library, the local newspaper told of her reputation:

Miss Leach is perhaps better known than any other one character upon the Oregon campus during this time. She knew personally every student from freshman to senior, and has hundreds of sincere friends among the Oregon graduates all over the state.4

Resistant to fully retiring, and beloved by faculty and students, Miss Leach continued to work in the new main library until 1914 when, at the age of 79 years, she became the founding librarian and administrative assistant at the new School of Architecture and Allied Arts. Her transfer to the new location was met with doubt by the founding Dean of the school, Ellis F. Lawrence, who was resistant to hiring a 79-year-old to the post. He expressed his doubts to the University President, and was reassured that Miss Leach could hold her own and make worthy contributions. Dean Lawrence described his first meeting with her as particularly memorable:

When I [met] her at the first staff conference I was very conscious that there was a divine fire in the proud little figure before me. It was shining through the brightest pair of the darkest eyes I have ever felt boring into my soul. After listening to my outline of procedure and objectives, Miss Camilla leaned over the table and in the snappy, crisp utterance I was later to know so well, she said, “Sir, I was teaching art before you were born.” If she had said ‘thirty years before you were born’, I feel sure she would have been within the truth. Naturally I thought – here is a Tartar to deal with, and anticipated plenty of excitement. Little did I know how deliciously that excitement was to be; how surprising and invigorating it could be! Miss Camilla was placed in charge of the Art Library. Before I knew it she had that department functioning more efficiently than I had thought possible, even in my fondest dreams. But her work did not stop there. She became our matriarch, tradition builder, exemplar of manners, personnel officer – and very much in evidence as advisor to the Dean.5

Indeed, students took to calling her the “Mother of Our Library” and Aunt Psyche (Pidgy), a

[G]uiding spirit since its inception….All of us have been visited by her kindly interest, – the serious have been led to that exact niche where Volume X lies; the frivolous (and everyone knows that some of us often go to the library on missions quite foreign to study), – we have been ushered into her acquaintance by the sharp tap of her pencil or by the censure of her warning nod. But however that may be, each of us, as we step out into the world, is to carry a pleasant recollection of Miss Camilla Leach.6

Another story of Miss Leach helping students, while displaying her expertise in French architecture, is noted in the Eugene Guard newspaper from Saturday, April 20, 1918: A girl on campus had a friend stationed in France, but the US military would not reveal the location. The girl’s friend sent her a photo with a cathedral in the background. The girl didn’t recognize it but another friend suggested she take it to Miss Leach, the art librarian. Sure enough, Miss Leach immediately identified the cathedral and the girl was able to locate her military friend.7

In addition to her teaching, library, and administrative duties, Miss Leach consulted with library colleagues and was in attendance at the earliest foundational meetings of the Oregon Library Association (1904). Her attendance at local arts events is well-documented in the local newspapers, as are the frequent talks she would give to local civic organizations (one titled “The Relation of Art to Library Work”), and her reputation as a fine sketch and free-hand artist was known throughout the Northwest.

Philosophy of Academic Rigor and Student Advocacy

Miss Leach had a sense of humor that she rarely indulged, but there were certain topics that were sure to raise her ire. In one instance, as regaled by Dean Lawrence in his memorial writing, a painting professor teaching Civilization and Art Epochs was discussing symbolism with his class. It was reported that he used the example of the serpent, once a symbol of wisdom, but over the years mixed together with many ingredients and encased in a skin, much like a sausage. This description, when relayed to an incensed Miss Leach, caused her to question why culture and wisdom should be treated with levity. She often wondered why artists and architects could not have higher academic standards. Dean Lawrence described her struggle with the habits of scholarship:

Knowledge was to her the basis of her philosophy and conduct, though she little knew how much her intuitions and her fine intellectual common-sense tempered that knowledge. … [T]he idiosyncrasies of the creative artists often irked her. Yet she came to participate valiantly in the methods of the School which called for the freedom necessary to bring out the creative urge in each student.8

To demonstrate how Miss Leach advocated for her students, Dean Lawrence told of a new student who worked extremely hard and produced decent results for one who had no artistic background, which thrilled Miss Leach. However, after flunking out at the end of the term, causing the student to leave without even a good-bye, Miss Leach arrived at the Dean’s office, furious at a system that would let go of a potential genius and lobbied on his behalf. She urged the Dean to reconsider the student’s case and bring it before the Faculty. Together they won the case and the student was reinstated and went on to “make good,” much to the satisfaction of Miss Leach.

Legacy

Miss Leach completed a handwritten history of the University of Oregon in 1900, likely one of the first written of the 24-year old institution, with a volume still found in the library’s Special Collections and University Archives department. During her time at UO, Miss Leach, along with other library and University staff, were interested in caring for French children affected by the war, particularly in 1919. This seems entirely appropriate and in line with Miss Leach’s fascination with French culture and arts.

Camilla Leach finally truly retired in 1924, primarily due to declining health after a fall, and losing her eyesight. She moved back east and died in Jonesville, Michigan (near Battle Creek) in 1930, while staying with a relative. Dean Lawrence wrote a tribute to Miss Leach after her death, describing her ultimately as an “exquisite cameo who was classic in her perfection.” He noted that she was in the process of translating Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students. The Racinet volume can still be found among the collections of today’s Design Library, which in 1992 was the focus of an expansion of Lawrence Hall, the home of the College of Design.

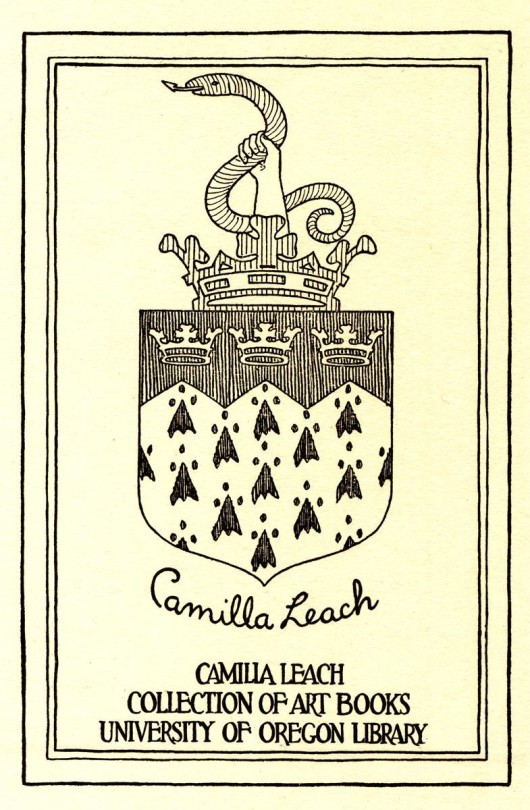

There are several other books still containing the bookplates indicating they were purchased with the fund set up for the “Camilla Leach Collection of Art Books,” a special collection in the University Library that remained well after Miss Leach’s death. The fund, set up in 1923, was described as a perpetual fund designed for purchasing art books from the interest earned each year. Mrs. Henry Villard, widow of one of the pioneer founders of the University, donated and suggested that a portion of the yearly endowment to the libraries from the Villard gift should be set aside to build up the Leach fund. There are several newspaper accounts of faculty members, and their families, donating books and financial support to the fund. In addition to books purchased, over the years as Miss Leach’s history became better known, library staff have unofficially named a two-story reading room the “Camilla Leach Room” in her honor. The room enables study and research and is used to present selections from the library’s collection of artist’s books, rare books, and other artifacts.

Perhaps the most touching of Miss Leach’s legacy is how she influenced her initial detractors. Dean Lawrence fancied himself a bit of a creative writer, and one can find several complete and incomplete short stories and novella manuscripts among his personal writings in the archives of the University of Oregon Libraries. In addition to the 6-page memorial tribute that Lawrence penned that was devoted to Miss Leach (excerpted above), one can also read an incomplete 60-page murder-mystery novella. The protagonist who is able to solve the case faster than the sheriff? A Miss Marple-like character named “Miss Camilla Chaffin” described as wearing a Paisley shawl, lace collar, and a lavender ribbon in her hair. She was the “oldest of the old-timers” and was friendly with the “dear old doddering Dean.”9

As we piece together Miss Leach’s legacy, her strength is revealed in her loyal determination to provide the best resources and environment for students in order to nurture their creativity and scholarly output. Her ability to expose interests, and proactively anticipate the materials needed for letting those interests flourish, were among her special gifts to the students she served and the colleagues she assisted. Her legacy continues today in the resources and services that are at the forefront of today’s Design Library.

Notes

1 “Untitled News Article,” Weekly Oregon Statesman, March 18, 1870, 3.

2 Program, Bryn Mawr College, p. 252. Accessed through Google Books.

3 “The ‘Apostle’ of Fresh Air…Margaret Comstock Snell (1844-1923)” George Edmonston Jr., OSU Alumni Association, undated. http://www.osualum.com/s/359/16/interior.aspx?sid=359&gid=1001&pgid=536

4 “Veteran U.-O. Librarian Retires with Honor,” Oregon Daily Journal, October 4, 1912.

5 Ellis F. Lawrence, “Miss Camilla – A Portrait” (Eugene, Ore., 1930), in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Ax 056, Box 13, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, 2.

6“Miss Camilla Leach,” in Oregana, 1912 vol., 23.

7“Censor Sleeps on Job,” Eugene Guard, April 20, 1918, 4.

8Ellis F. Lawrence, “Miss Camilla – A Portrait” (Eugene, Ore., 1930), in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Ax 056, Box 13, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, 4-5.

9 Ellis F. Lawrence, “The Red Tide,” in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, also in Harmony in diversity : the architecture and teaching of Ellis F. Lawrence, edited by Michael Shellenbarger, Eugene, Or. : Museum of Art and the Historic Preservation Program, School of Architecture and Allied Arts, University of Oregon, 1989.

Other sources consulted

● 1903 Webfoot (University of Oregon Yearbook)

● Bishop’s Oakland Directory for 1880-81 “Containing a business directory, street guide, record of the city government, its institutions, etc.” (varies). “Also a directory of the town of Alameda” (issues for <1880-81-> also include Berkeley). Compiled by D.M. Bishop & Co. Description based on: 1876-7. Published: San Francisco : Directory Pub, Co., <1880-> Open Library OL25463540M. Internet Archive bishopsoaklanddi187778dmbi. LC Control Number 11012620. https://archive.org/details/bishopsoaklanddi188081dmbi (Listed as teacher at Snell’s Seminary)

● “Board of Education,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1865, 4.

● “Board of Education,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 22, 1878, 4.

● “East Alabama Female College,” South Western Baptist, November 17, 1859, 3.

● “Former Undergraduates That Have Not Received Their Degrees,” in Program Bryn Mawr College, 1903-04, 1906, 283, https://books.google.com/books?id=GKRIAQAAMAAJ.

● “General Register of the Officers and Alumni 1873-1907,” vol. 5, no. 4, University of Oregon Bulletin (Eugene, Ore.: University of Oregon, 1908), http://hdl.handle.net/1794/11152.

● “Gift of $100 Received,” Eugene Guard, November 6, 1924, 12.

● Henry D. Sheldon, The University of Oregon Library 1882-1942, Studies in Bibliography, No. 1 (Eugene, Ore.: University of Oregon, 1942), http://hdl.handle.net/1794/23064.

● “New York State Census, 1855,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BPY-97K6?cc=1937366&wc=M6G3-GZ7%3A237407901%2C237457701 : 22 May 2014), Orleans > Kendall > image 15 of 40; county clerk offices, New York. (teacher at 19)

● “Salary Dispute,” The Illinois [Chicago] Schoolmaster A journal of educational literature and news v. 4 1871, 260 https://ia601409.us.archive.org/5/items/illinoisschoolma41871gove/illinoisschoolma41871gove.pdf

● “SPOTLIGHT ON A LEGACY: Treasures of the Design Library” Ed Teague, 2014, https://library.uoregon.edu/design/century

● “TAE Academy,” Placerville Mountain Democrat, August 10, 1878, n.p.

● “United States Census, 1900,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MSDX-B6R : accessed 15 April 2018), Camilla Leach in household of Mary E Cox, South Eugene Precincts 1 and 2 Eugene city, Lane, Oregon, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 112, sheet 8A, family 162, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,241,348. (age = ten years younger)

● “Untitled News Piece,” Eugene Guard, May 1, 1928, 6. – Talk “Relation of Art to Library Work”

● “What’s in a Name? Design, and Library” Ed Teague, Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Sept. 12, 2017. http://www.acsa-arch.org/acsa-news/read/read-more/acsa-news/2017/09/12/what-s-in-a-name-design-and-library

This post was written by Dr. Theodosia T. Shields & Doris Johnson and submitted on behalf of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. Last year’s post on Amanda Rudd was also brought to us by BCALA.

For over forty years Dr. Barbara Williams Jenkins greatly contributed to the library profession on a local, regional and national level. Even after retiring, she continues to contribute to her beloved profession.

Barbara was born in Union, South Carolina but grew up in Orangeburg, South Carolina, where she received her high school diploma from Wilkinson High School. She graduated from Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina, with a B.A. degree and earned a MSLS from the University of Illinois, Urbana, IL. Her post-Master’s work included advance study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Atlanta University and Clemson University. These subsequent educational experiences were followed by her studying and receiving her Ph. D. in Library and Information Sciences from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick in 1980.

Her professional career began in her hometown of Orangeburg as a Reserve and Circulation Librarian at South Carolina State in 1956. After serving in this role for two years, she became the Reference and Documents Librarian. This was followed by her becoming Library Director at South Carolina State in 1962 where she served until 1987. In 1987 she was promoted to Dean of Library and Information Services at South Carolina State. She served as Dean until her retirement in 1997.

During her tenure at South Carolina State (now known as South Carolina State University), Barbara served with distinction in all roles. At the only public supported Historically Black College and University in South Carolina, Barbara worked diligently to provide leadership on the campus, in the state and beyond. She was an advocate for the library program.

Some of the leadership roles that she assumed included the following: the first African American President of the South Carolina Library Association 1986-1987; Southeastern Library Association- College Section Director 1978 – 1980; American Library Association Council 1978-1982; Association of National Agricultural Library, Inc. 1890 Land -Grant Library Directors’ Association Tuskegee University (President 1979-85); American Library Association Black Caucus – Chairperson 1984-85, Southeastern Library Network ( SOLINET) - Board of Directors 1989-92; and South Carolina Governor’s Conference on Library and Information Services (1978 – 1979) and National Endowment for the Humanities – Evaluator – 1979. In 1969 she served as a Library Evaluator – Institutional Self- Study for the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). She continued to serve in this capacity until her retirement in 1997. She also served on the College Consulting Network in 1991 and served until retirement.Because of her love of African American history and her passion for preserving that history, she was a member of the African-American Heritage Council and the Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation. As a collector of African American history and a researcher, she played a significant role in the establishment of the institution’s historical collection. Her work extended beyond campus by her affiliation with the South Carolina Archives & History Commission. She was instrumental in locating and identifying campus historical sites and buildings in Orangeburg along with providing training sessions on how to preserve this history. Her actions led to her becoming a charter member of the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission.

For her service to the campus community and beyond, she received many accolades and awards during her career. She received the “Boss of the Year Award” in 1980 from the Orangeburg Chapter of the Professional Secretaries International; 1890 Land-Grant Director’s Association Award 1978-84; President’s Award, South Carolina Library Association, 1987; South Carolina State College Distinguished Service Award, 1991; SOLINET Board of Directors Service Award, 1992 and the college’s First President’s Service Award in 1997. Additionally, on February 27,2000 at the Founders’ Day program, Dr. Leroy Davis, President of South Carolina State University bestowed upon Dr. Jenkins the first emeritus award.

As a leader and advocate for the profession, Dr. Jenkins worked diligently to share and instill these values with her staff and others in the profession. She served as a role model for many librarians.

In addition to a very active professional life, she also held memberships in many civil and social organizations including Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc. (Past Regional Director for the South Atlantic Region). She is also a member of the Williams Chapel AME Church.

She was married to the late Robert A. Jenkins and they had two children and five grandchildren. As a retiree she continues to devote her time to African American and local history. She also loves to talk about the library profession and continues to serve as a role model for librarians and aspiring librarians.

Works Cited:

“Spotlight on Dr. Barbara Williams Jenkins” http://www.scaaheritagefound.org/call_response2009fall.pdf

“Retirement: A New Beginning Reflections of Dr. Barbara W. Jenkins and Mrs. Eartha J. Corbett”, June 7, 1997 Kirkland W. Green Student Center, South Carolina State University.

This post was written by Polly Thistlethwaite, Chief Librarian, The Graduate Center, City University of New York. The photo above, taken by Liz Snyder in 2013, shows BC Sellen and Polly Thistlethwaite in New Orleans.

Betty-Carol “BC” Sellen was born 1934 in Seattle, WA. She is a librarian and a collector of American folk and outsider art and author of several resource books on the subject. She attended the University of Washington for both her Bachelor’s (1956) and Master’s (1959) degrees, and she earned a second Master’s from New York University in 1974. She held positions of increasing responsibility in the profession, starting at the Brooklyn Public Library (1959-60), then with the University of Washington Law Library (1960-63), and finally at the City University of New York Brooklyn College Library from 1964 until her retirement in 1990 as Associate Librarian for Public Services. She resides in Santa Fe, NM, and also spends time in New Orleans, LA.

As a library school student at the University of Washington, Sellen engaged with student government to pressure the university to concern itself with housing for students of color, with particular focus on students from Africa who struggled to find places to live. A media campaign called attention to discriminatory city housing practices and forced the university to support students impacted by them.

Sellen’s librarianship provided a platform for wide-ranging activism, gaining particular notoriety for her work on feminist issues in the profession. Sellen was active in the founding of the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table, a co-founder and 1982-3 chair of the ALA Feminist Task Force, and chair of the Committee on the Status of Women in Librarianship following that.

With a cohort of librarian feminists, she organized an American Library Association Preconference on the Status of Women in Librarianship sponsored by the Social Responsibilities Round Table Task Force on the Status of Women in 1974 at Douglass College, Rutgers University. In the Introduction to the proceedings from that Preconference [1], Sellen describes initial meetings of the group with the incisive directness characteristic of her commentary:

Most of this first meeting was consumed by men telling the women how to improve themselves, and furthermore that what the profession really needed was more men to improve the image. In spite of these helpful suggestions and the scornful attitude of many male SRRT members, who fancied themselves a part of the macho left, where women’s issues were considered frivolous, the women were able to organize together and to become an active and notable presence at ALA conference meetings.

Sellen further explains her cohort’s librarian-focused strategies to “utilize talents and abilities already present among women librarians and not call up experts or ‘big names’ outside the profession” to build professional self-reliance in a likely long-term struggle against systemic oppression.

The preconference generated tangible results: a national survey about union types and priorities; a feminist librarian directory and support network S.H.A.R.E. (Sisters Have Resources Everywhere); a library education resolution presented to ALA membership directing the Committee on Accreditation to practice nondiscrimination in hiring and promotion of library school members; a statement to ALA regarding the Ford Foundation-funded Council on Library Resources to examine grant awarding and promotion practices; a variety of watchdog efforts directed at library schools, the library press, and professional journals; and the recommendation that a daily ‘sexist pig’ award be reported in the ALA Conference Cognotes publication with accompanying instruction about how to make nominations for it. The conference also generated resolutions presented to the ALA for deliberation during the 1974 Annual Conference Meeting in New York City involving accreditation, child care services, position evaluation, sexist terminology, support for affirmative action, terms of administrative appointment, and women in ALA Council positions.

Sellen was also active in New York City library politics. She was President of the Library Association of the City University of New York (LACUNY) [2] during the tumultuous years of 1969 – 71 and co-chair of the 1968 LACUNY Conference [3] New Directions for the City University Libraries that laid the groundwork for the CUNY union catalog and growth of the productive coalition of CUNY libraries. Sellen’s engagement with library politics around the country introduced varieties of library organization, policies, and political concerns into CUNY library activism.

Sellen was engaged in efforts to obtain and to maintain faculty status for CUNY librarians, to match the salaries, benefits, and prestige afforded other university faculty colleagues, achieved in 1965 [4]. In her role as president of the LACUNY Sellen encouraged librarians to publish in scholarly and literary journals as appropriate platforms for librarians’ work. She wrote Librarian/author: A Practical Guide on How to Get Published (Neal-Schuman, 1985) to further that concern.

Sellen was also a defender of academic freedom. When Zoia Horn, librarian at Bucknell College in Lewisburg, PA, was jailed for refusing to turn over library borrowing records regarding the Berrigan brothers (who were imprisoned for anti-American activities) [5], Sellen organized NYC fundraising to support Ms. Horn’s legal defense. [More from WoLH on Zoia Horn here–ed.]

Sellen valued collaboration and often co-authored her academic and professional work on library salaries, alternative careers, and feminist library matters. She was a prodigious author of letters-to-the-editor of library professional publications. She wrote brief, widely-read letters for American Librarians and Library Journal on topics such as librarian faculty status, the sexist underpinnings of the librarian image problem, intellectual freedom in Cuba, sexism and salary discrimination in the library profession, suppression of gay literary identities, and on unacknowledged incidents of censorship. In 1989 she criticized appointment of Fr. Timothy Healey to head the New York Public Library on the grounds that as a CUNY administrator, prior to his NYPL appointment, Healey had systematically undermined librarians and libraries. Sellen remembered publicly that Healey, in a CUNY meeting she attended, announced that “college librarians were about as deserving of faculty status as were campus elevator operators” [6], exposing a cluster of problematic biases held by a man appointed a leading NYC cultural administrator.

In the 1970s, Sellen convinced several other librarians, including Susan Vaughn, Betty Seifert, Joan Marshall, Kay Castle, to take up residence on E. 7th Street in New York City’s East Village. She resided at 248-252 East 7th St. Sellen joined with a multi-ethnic group of residents to rehab neighborhood buildings and establish them as self-governed cooperatives. Sellen was active in the same block association that battled the drug trade that flourished in the neighborhood as early as the 1970s and continued into the 1990s [7].

In 1990 Sellen received the ALA Equality Award, commending her “outstanding contributions toward promoting equality between men and women in the library profession.” The commendation recognizes her tireless labor and sustained coalition building as a leader in several landmark conferences on sex and racial equality, and her “inspiration to several generations of activist librarians.”

Sellen’s eclectic expertise was reflected in her published works. She assembled and edited The Librarian’s Cookbook (1990). She co-authored The Bottom Line Reader: A Financial Handbook for Librarians(1990);The Collection Building Reader (1992) and What Else You Can Do with a Library Degree(1997).

In her retirement, Sellen became an accomplished collector of American folk art. She authored and co-authored several reference books on the topic, including 20th Century American Folk, Self-Taught, and Outsider Art (1993) and Outsider, Self-taught, and Folk Art: Annotated Bibliography (2002) with Cynthia Johanson; Art Centers: American Studios and Galleries for Artists with Developmental or Mental Disabilities (2008); and Self-taught, Outsider and Folk Art: A Guide to American Artists, Locations, and Resources(2016).

Footnotes

1. Marshall, Joan; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1975). Women in a women’s profession: strategies: proceedings of the pre-conference on the status of women in librarianship. American Library Association.

2. Schuman, Patricia; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1970). Libraries for the 70s. Queens College, City University of New York.

3. Sellen, Betty-Carol; Karkhanis, Sharad (1968). New Directions for the City University of New York: Papers Presented at an Institute. Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York.

4. Drobnicki, John A. (2014). CUNY Librarians and Faculty Status: Past, Present, and Future. Urban Library Journal 20(1).

5. Horn, Zoia. (1995). Zoia! Memoirs of Zoia Horn, Battler for People’s Right to Know. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

6. Sellen, Betty-Carol. (June, 1989). Healy: Unequivocal Dismay. Library Journal, p. 6.

7. Pais, Josh et al. 7th Street. (2005). Video. Paradise Acres Productions.

Our final post for Women’s History Month 2017 comes again from Lorna Peterson, Emerita Associate Professor, University at Buffalo. The photo above was provided by family and printed on memorial service program and online obituaries; see The Oberlin News Tribune from Feb. 23 to Feb. 24, 2017 (accessed March 16, 2017)

Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins

February 27, 1936 - November 11, 2016

Raised on Historically Black College and University campuses (HBCUs) as well as two years in Monrovia, Liberia by her professor and diplomat father and librarian mother, influenced by a Quaker education in Iowa, and educated at a Seven Sisters college and an Ivy League university both in New York City, Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins lived an outstanding librarian career that encompassed the transitions of the United States civil rights era.

With the enactment of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, the development of public policy to implement the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 was challenged by competing philosophies of integration versus black separatism within the black community. One response to that challenge was the establishment of a consortium and research institute of social scientists called MARC, Metropolitan Applied Research Center. Founded by psychologist Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, an aim of the institute was to provide a non-partisan forum for discussion between black and white politicians at city, state, and federal levels regarding the issues, policies and programs most relevant to the officials’ constituents and communities. Central to the MARC institute and its work was the library, and the head of that library was Betty L. Jenkins. Building the collection and directing the library influenced Ms. Jenkins’s own research and publication output. Her contributions to understanding race relations in the United States, as well as in American librarianship, are unique and foundational.

Born February 27, 1936, in Harris County, Texas, to professor, college administrator, and diplomat Ralphael O’Hara Lanier and librarian Garriette Lucile Green(e) Lanier, Betty was raised on the campuses of Texas State University for Negroes (now Texas Southern University), Hampton Institute (currently Hampton University), and other HBCUs along with her younger sister, Patricia. The family lived in Monrovia Liberia from 1946-1948, where her father was U.S. Minister to Liberia.

Educated for high school at the Quaker Scattergood Friends School in West Branch, Iowa, she developed a lifelong respect for Quaker principles, although she did not become a member of the Religious Society of Friends. She began her first college year at Grinnell College in GrinnelI, Iowa, and then transferred to Barnard College in New York City, where she earned a BA degree in history. Following the baccalaureate degree, she entered and graduated from the MS program in Library Service at Columbia University and later earned a MA in American history from New York University.

As part of her duties at MARC and at the request of the Hastie Group, Betty Jenkins, along with Susan Phillis, compiled and published the annotated bibliography Black Separatism in 1976. The bibliography is organized by two parts. Part 1 concerns separatism vs. integration within a historical perspective, citing and annotating materials from 1760-1953 and then followed by the twenty years since BrownvBoard of Education. Part 2 lists citations concerning the institutional and psychological dimensions regarding identity, education, politics, economics, and worship within the context of segregation and desegregation. Works that concern redressing racial inequities are also documented in Part 2 of the bibliography.

Betty Jenkins was a bibliographer and scholar librarian who published, presented, and created exhibits that documented the black experience in America. Works by Betty Jenkins include but are not limited by the following:

• a bibliographical essay written with Donald Franklin Joyce, “Aiming to publish books within the purchasing power of a poor people”: Black-owned book publishing in the United States, 1817-1987,” Choice February 1989, vol. 26, pages 907-913;

• solo authored and groundbreaking critical race biography of Ernestine Rose: “A white librarian in black Harlem,” Library Quarterly; July 1990, Vol. 60, pages 216-231; and

•Kenneth B. Clark: A bibliography, MARC 1970, 69 pages.

With assistance from the City College of New York (CCNY) Libraries, these additional contributions by Betty Jenkins are identified:

• CCNY issue of The Campus February 19, 1991: “Leading City College Black Faculty Discuss their Progress and Achievements at CCNY,” which is based on an event partly organized by Betty Jenkins;

• Principal Investigator for a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to host a conference and create conference proceedings for “We Wish to Plead our Own Cause”: Black-Owned Book Publishing in the United States 1817-1987 held May 1988 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of NYPL;

• One of the curators of the CCNY Libraries Cohen Library Atrium exhibit “Parallel Worlds: African Americans in Harlem and Paris in the 1920s” February-June 2001.

As well as working for various libraries in the CCNY system, Betty Jenkins also worked at Howard University. Through her careful scholarship of bibliography, mounting exhibits, and writing a librarian biography within a context of race conflict and cooperation, Betty L. Jenkins preserved and interpreted the history and lives of Americans, particularly black Americans.

References

Ancestry.com. Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data: Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997. Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services. Microfiche.

Obituary of Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins of Oberlin Ohio, Dicken Funeral Home

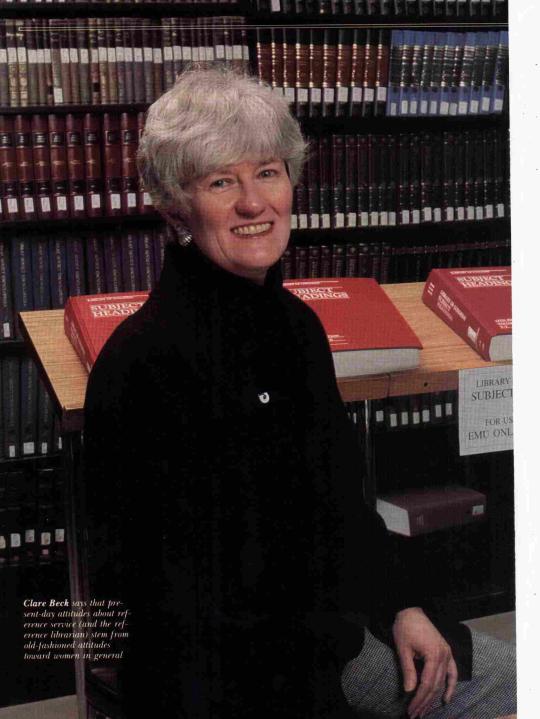

Photo from Library Journal, Volume 116 Issue 7, April 15, 1991, page 32; Eric Smith possible photographer. Caption reads “Clare Beck says that present-day attitudes about reference service (and the reference librarian) stem from old-fashioned attitudes toward women in general.”

Today’s post is from Lorna Peterson, PhD, Associate Professor (emerita), University at Buffalo. This is Lorna’s fourth (!) year writing for WoLH; she has previously submitted posts on Aurelia Whittington Franklin(2016),Leonead Pack Drain-Bailey (2015), and Clara Stanton Jones(2014).

Government documents librarian and feminist librarian historian Mary Clare Beck was born and raised in the American Midwest and is a graduate of the University of Chicago with an A.B. in history. She earned the Master of Library Science degree from the University of Denver, and a MA in interdisciplinary social studies from Eastern Michigan University. Her reading in sociology for the MA degree is where her interest to apply gender theory to the examination of the gendered dynamics of librarianship was generated. The result of this interest is a body of research that invigorates library and librarian history.

Beck’s career at Eastern Michigan University was one of achievement and honor when she retired at the rank of full professor from the University Library. Beck’s achievements include but are not limited to, being one of the founders of GODORT, the American Library Association’s Government Documents Round Table, giving invited lectures on library history, and championing librarianship by writing letters to library publications and educating the general public regarding library topics by publishing letters in national periodicals. Examples of such letters are “Defending the Depositories” published in Library Journal(February 15, 1988), a letter that appeared in the March 30, 2009 Wall Street Journal critiquing the press coverage of Laura Bush’s professional librarian role in contrast to the First Ladies who were lawyers, and comments on a proposed remodel of the NYPL research library which appeared January 10, 2012 in The Nation. As an alumna of the University of Chicago, Clare Beck has contributed to the alumni magazine regarding library matters with her “The importance of browsing,” which tempered for her fellow University of Chicago graduates the allure of automation with the appeal of serendipitous perusing of library stacks.

It is Clare Beck’s contribution to library science research, particularly historical research, where her greatest achievements are. Through enriching library science scholarship by examining the complexities of gender issues, Clare Beck advanced library science research beyond the studies of administrative positions and gender. With critical analysis through the lens of feminist theories and gender studies, Ms. Beck added significantly and uniquely to the library literature canon.

Her work, “Reference Service: A Handmaid’s Tale” (Library Journal, April 15, 1991, p. 32-37) examines library reference work and its 1980s self-identified crisis through the lens of gender. Citing sources outside of the discipline of library science, Beck’s article gives the profession a fresh way to frame the tradition as articulated by librarian Samuel Green, of having a helpful sympathetic friend at a desk to take random on demand requests. [ed. note: if you have access to Library Journal archives, you should look up and read this article. A representative quote: “Thus we have the concept of on-demand service provided by a woman at a public desk, always ready to lay aside other work to respond ‘incidentally’ to questions. The underlying image would seem to be that of Mother, always ready to interrupt her housework to attend of the problems of others.”]

Beck’s other works include “Genevieve Walton and library instruction at the Michigan State Normal College” College and Research Libraries (July 1989). Genevieve Walton has a profile in the Women of Library History blog. Archival research figures prominently in “A ‘Private’ Grievance against Dewey,” American Libraries (Jan 1996, Vol. 27 Issue 1, p62-64), a model work of library event history that goes beyond chronology and biography that is not hagiography. [ed. note: again, if you have archival access to American Libraries, give this one a read.]

“Fear of women in suits: dealing with gender roles in librarianship” was presented at the University of Toronto and then published in the highly regarded Canadian Journal of Information Science Vol. 17 no. 3, pp.29-39, 1992. Her biography of Adelaide Hasse, The New Woman as Librarian: The Career of Adelaide Hasse, Scarecrow Press, 2006, is rich with archival material and careful analysis .

Invited lectures such as “How Adelaide Hasse got fired: A feminist history of librarianship through the story of one difficult woman, 1889-1953,” as organized by Cass Hartnett of the University of Washington, “Fear of Women in Suits: Dealing with Gender Roles in Librarianship,“ and "Gender in Librarianship: Why the Silence?” (given at the Canadian Library Association conference) introduced professional librarians, library workers, and graduate library science students to a sociological feminist examination of the library and information science professions. In her career, invited talks and juried presentations were given at such organizations as the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters (MASAL), Library and Information Science section, and ALA Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL).

Clare Beck’s contribution to library history advances our field with rigorous, iconoclastic research, enriching the understanding the practice of North American librarianship.

This post, including the image above, comes from Karmen Beecroft, Digital Projects Librarian for Digital Initiatives at Ohio University. I’ve put in a cut, so make sure you click through to read the entire post!

The eleventh of twelve children and the youngest daughter, Anne Claire Keating was born to Irish immigrant parents on February 25th, 1879 in Terre Haute, Indiana. Her father Edward, a stone mason—and “artist in marble” according to one newspaper– had arrived on American shores some eighteen years previously, at the beginning of the Civil War.(1) In Missouri, he met and soon married Ellen Cadden, herself a childhood transplant from the Emerald Isle. Half of Ellen’s children would die in the coming decades, but stalwart Anne seldom left her mother’s side.

Then known as Anna, Keating graduated Terre Haute High School in 1897 and immediately enrolled in the nearby Indiana State Normal School, which she attended until 1899. At the turn of the century, she dropped out to become Second Assistant Librarian under the direction of Arthur Cunningham, founder of the Normal School library. In 1901, Keating received a promotion to first assistant librarian, a position she would continue to hold for another two decades—minus a leave of absence from September 1907 to June 1908 to complete her library science degree at the Pratt Institute in New York. During that period, she lived in a Brooklyn boardinghouse while also attending the Brooklyn Institute as a “special student.” Her married sister Margaret lived nearby, helping her settle in and attending her when a sudden “nervous affection” which “made it painful for her even to dress her hair” kept her out of school for two days.(2) In the coming years, the two would several times vacation together on the coast for extended periods in service to Keating’s health.

Upon completing her degree, Keating returned to her parents’ home in Terre Haute, which she also shared with her widowed sister Mary. Her father and eldest brother both died in 1913; the three women moved out of the family home soon after. As president of the Terre Haute Women’s Club and patroness of the Alpha Section of the Normal School Women’s League, Keating frequently made the local papers while promoting educational lectures and mentoring her younger sorority sisters. At the library, she assumed the duties of cataloger during a period of great expansion while somehow also finding time to pursue graduate coursework at the University of Wisconsin. A satirical student publication issued around this time sketches the scene at the Normal School library in a few lines:

Misses Marshall, Keating, Darrow and Brown,

Cunningham’s satellites, and ne’er do they frown;

Four good varieties, thick, fat, and thin;

At five o’clock, mornings, their work it begins.(3)

At the age of 42, it seemed as though Keating had finally gotten her big break when a position opened up as head of the Muncie branch of the Normal School library. “I anticipate a very pleasant time at Muncie,” she told the Terre Haute Saturday Spectator. However, Keating’s mother died while preparing to make the move, derailing her ambitions; Keating remained in Terre Haute. Four years later, another opportunity for advancement arrived hand-in-hand with personal tragedy. In January 1925, her six-year-old niece Frances, of whom she had partial custody, developed acute laryngitis while in her aunts’ care and died suddenly. Several months later, Keating, then 46, left her family and hometown to assume the position of Ohio University Librarian in the small Appalachian town of Athens, some 350 miles east of Terre Haute.

Keating, the university’s third Librarian and the first woman to fill that role, arrived at Athens with an agenda. The Green and White, Ohio University’s student newspaper, reported that

the very smell of the paint and varnish used in the library redecoration attests to the initiative and leadership of the new librarian. Several changes in location and library procedure have already been announced, and are now being planned and executed. Stacks privilege[s] to be granted to students soon[; this] comes from Miss Keating’s effort to make the library more useful and attractive.(4)

Keating immediately embarked upon an ambitious remodeling plan for the crowded Carnegie Library, including “a new reference room and more commodious reading room,” as well as “a better and more complete children’s room.” In 1925, Keating’s charges numbered just 50,000 books and four assistants.

Echoing her Terre Haute occupations, Keating swiftly moved to embed herself in the Athens university culture, becoming first secretary and later president of the OU chapter of the American Association of University Women. A dedicated patroness of the Theta Phi Alpha sorority, she often collaborated with popular Dean of Women Irma Voigt to facilitate student programming and provide mentorship. An enduring autodidacticism led Keating to pursue a fifth course of study at George Washington University and by 1931 she had added a Bachelor of Arts degree to her ever-growing portfolio.

1931 also saw the completion of the Edwin Watts Chubb Library and the transfer of the Carnegie stacks—now housing 70,000 volumes—to the new building. Chubb Library provided space for some 240,000 books and 600 simultaneous readers, a threefold increase over the study space available at Carnegie. Head counts conducted by Keating’s staff revealed that the new library received 20,000 visits a month during the opening years of the Great Depression, a great increase over usage patterns observed in the 1920s. The incoming university president Herman James dealt the Library’s newfound popularity a blow, however, when he directed that Keating’s decade-long open stacks policy be discontinued. “It is felt that lower classmen are not ready for undirected browsing among so many volumes,” Keating reservedly reported to The Green and White. “They must first be educated for this responsibility.” (5) The closed stacks mandate proved extremely unpopular in subsequent years, though Keating noted in exasperation that only half the senior class ever reported to receive their passes. Nevertheless, she continued to remove barriers when able, adding a fiction-heavy open shelf collection just a semester after James’ announcement.

In 1937, Keating returned to her Normal School roots with the development of a 3-credit course for prospective educator-librarians. Keating tartly noted that her class—the first in school library administration offered by a state university in Ohio– “in no sense prepares the student for full time librarianship.”(6) Though enrollment varied, Keating continued to offer the course for twelve years until her retirement in 1949 at the age of 70.

Over the 24 years of her tenure at OU the student body as a whole grew 400%. Keating reacted by growing the collections to 180,000 volumes and increasing her staff to 12 assistant librarians and three clerical assistants. An army of fifty student workers sprang up to deal with the closed stacks system and increased circulation. Keating’s retirement coincided with that of Dean Voigt, her longtime collaborator. The Ohio Alumnus hinted at intriguingly unspoken controversies during their long careers: “both women were in positions in which it was impossible to please all person having dealings with them. There are doubtless those who do not agree with some of their actions and decisions. But, many fewer, we’ll warrant, is the number who do not credit them with an earnest desire to deal fairly in the matters within their wide jurisdictions.”(7)

Upon quitting Athens, Keating joined her sister Margaret in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, until Margaret’s death in 1952. At the age of 73, Keating returned for a last time to Terre Haute to live with her widowed sister-in-law Clara. A few months later, Keating herself died of heart disease. From “Cunningham’s satellite” to university administrator, Anne Keating’s life is one of conflicting drives and stymied ambitions finally realized. As an unmarried daughter, her responsibilities were culturally prescribed by the needs of the family, even as her remaining family members assumed responsibility for her welfare later in life. She never let these pressures constrain her mind, however—during the 26 years she served at the Normal School library, she pursued coursework through three different universities and sought continually to further her education through reading and lectures. At Ohio University, her evenhanded management saw her library safely through the Great Depression and World War II. Though she personally disliked publicity, “Miss Keating’s” legacy is indeed a very public one—the modern library system she founded, with its emphasis on pedagogy and usability, forms the basis of our institution today.

Notes

1 Terre Haute Saturday Evening Ledger [Terre Haute, IN] 2 April 1881: 8.

2 Terre Haute Sunday Spectator [Terre Haute, IN] 16 November 1907

3 Denehie, Elizabeth. “A Eulogy on our Faculty.” Normal Advance [Terre Haute, IN] June 1915: 309.

4 “Introducing Miss Keating.” The Green and White [Athens, OH] 9 February 1926: 1.

5 “New Library Rules Issued.” The Green and White [Athens, OH] 27 September 1935: 1.

6 The Green and White [Athens, OH] 26 February 1937: 4.

7 Williams, Clark E. “From the Editor’s Desk” The Ohio Alumnus [Athens, OH] May 1949: 2.