#new york history

Hudson Valley History Reading Festival

Saturday, April 23, 2022

Hudson Valley History Reading Festival

Location: Henry A. Wallace Center*

Time: 10:00 a.m.to 3:00 p.m.

*Hybrid (In person at the Henry A. Wallace Center, and streamed to social media).

The FDR Library and the Friends of the Poughkeepsie Public Library District present the ninth annual Hudson Valley History Reading Festival on Saturday, April 23, 2022. In four sessions, beginning at 10:00 a.m., authors of recently published books on Hudson Valley history will present author talks followed by book signings. This event will be held in the Henry A. Wallace Center at the FDR Presidential Library and Home (and streamed live to the official FDR Library YouTube, Facebook & Twitter accounts). Copies of the authors’ books will be for sale in the New Deal Store located in the Wallace Center. This is a free public event, but registration is recommended for in-person attendees.

REGISTER HERE (In-person attendees only):https://events.r20.constantcontact.com/register/eventReg?oeidk=a07ej3saa87d6bb2ac5&oseq=&c=&ch=

10:00 a.m.

A.J. Schenkman

Patriots and Spies in Revolutionary New York

Stream Link: https://youtu.be/xhFLwpT4Akk

11:00 a.m.

Robert Titus and Johanna Titus

The Catskills in the Ice Age: Third Edition, Revised and Expanded

Stream Link: https://youtu.be/XcmwBu9ZHQM

NOON:

LUNCH BREAK

1:00 p.m.

Russell Dunn and Barbara Delaney

Paths to the Past: History Hikes through the Hudson River Valley, Catskills, Berkshires, Taconics, Saratoga & Capital Region

Stream Link: https://youtu.be/UdDNt5sNvRY

2:00 p.m.

Shannon Butler

Roosevelt Homes of the Hudson Valley: Hyde Park and Beyond

Stream Link: https://youtu.be/PuXpuVNWAbQ

The scarce decorative advertising broadside from the 1860s is currently on loan from the George Glazer Gallery to a temporary exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York. New York on Ice — currently on view until April 15th — is an entertaining look at the history of ice skating in the city (lower right in the installation photo). The print is featured in a section on the skating craze in the mid 19th century, when the Central Park Lake drew huge crowds of New Yorkers of all ages and social classes. The broadside advertises skating equipment sold by a Lower Manhattan sporting goods store in a playful composition that is over three feet wide. Also available after the exhibition closes at a special sale price –

email us at [email protected] if you’re interested! More info about the exhibition is at http://bit.ly/mcnyice

Post link

“New York.–John Valtz and Martin Hart each fined $5 for sticking out tongues at policemen.”

~The day book. (Chicago, Ill.), 07 Aug. 1915. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

President Roosevelt himself took this photograph of Daisy Suckley in the White House as she went through various papers, February 10, 1942. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

This post was written by Keith Muchowski, an Instruction/Reference Librarian at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn, New York. He blogs at thestrawfoot.com.

Margaret Suckley was an archivist at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York from 1941 to 1963. But she was much more than that.

“Daisy” Suckley, as she was known to friends and family, was born in Rhinebeck, New York in 1891 and grew up on Wilderstein, the family estate on the Hudson River not far from the Roosevelts’ own Springwood in Hyde Park. This was a small, rarefied world and in the ensuing decades Daisy saw sixth cousin Franklin’s rise to prominence. She eventually became one of his closest friends and confidants, sharing the good times and the bad with the country’s only four-term president. Ms. Suckley was there for Franklin in the 1920s when he was struck paralyzed from the waist down with polio, knew him during his years in Albany when he was New York governor and he became a national figure, attended the presidential inaugural in 1933 in the depths of the Great Depression, offered a discreet and comforting ear during the dark days of the Second World War when, as commander-in-chief, he made difficult and lonely decisions affecting the lives of millions around the world. Finally, Daisy was one of the inner circle present in Warm Springs, Georgia when the president died in April 1945. Roosevelt was inscrutable to most—some called him The Sphinx—but if anyone outside his immediate family knew him, it was Margaret “Daisy” Suckley.

Ms. Suckley (left) in Roosevelt’s private office at the presidential library with actress Evelyn Keyes, and Library Director Fred Shipman. Ms. Keyes is holding the album-version of Ms. Suckley’s book The True Story of Fala, October 31, 1946. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

There were perks to being Roosevelt’s close friend. The two enjoyed picnics and country drives. Both loved to dish the gossip about Washington politicos and the Hudson River Valley families they had known for decades. Daisy helped President Roosevelt design his Hyde Park retreat, Top Cottage. She enjoyed the “Children’s Hour” afternoon breaks when Roosevelt would mix cocktails for himself and his friends to unwind. There were getaways at Shangri-La, the rustic presidential retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains known today as Camp David. She attended services at Hyde Park Church with the First Family, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth when the royals visited in 1939. It was she who gave him Fala, the Scottish Terrier to whom he was so attached after receiving the pooch as a Christmas gift in 1941.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood at a podium on the grounds of his family home in Hyde Park and dedicated the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library on June 30, 1941. He was still in office at the time, having won re-election to an unprecedented third (and eventually fourth) term seven months previously. Roosevelt clearly believed that libraries and archives were themselves exercises in democracy in these years when fascism was spreading around the world. Ever the optimist even as World War Two raged in Europe and the Pacific, Roosevelt declared “It seems to me that the dedication of a library is in itself an act of faith. To bring together the records of the past and to house them in buildings where they will be preserved for the use of men and women in the future, a Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.” Then he quipped to the two thousand gathered about this being their one chance to see the place for free.

Roosevelt had been an unrepentant collector since his earliest boyhood days, with wide-ranging interests especially in naval history, models ships, taxidermy, philately, books on local history, political ephemera, and—probably above all—anything related to the Roosevelt clan itself. His eight-years-and-counting administration had already produced reams of material via the myriad alphabet soup New Deal agencies that had put millions of Americans to work during the Great Depression. It was becoming increasingly obvious in that Summer of 1941 that the United States would likely become entangled in the Second World War; as Roosevelt well understood, that would mean even more documents for the historical record.

Presidential repositories of various incarnations were not entirely new. George Washington had taken his papers with him back to Mount Vernon after his administration for organization. Rutherford B. Hayes, Herbert Hoover, and even Warren G. Harding had versions of them. Nora E. Cordingley (featured in a March 2018 Women of Library History post) was a librarian at Roosevelt House, essentially a de facto presidential library opened in 1923 at Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace on Manhattan’s East 20th Street whose papers and other materials eventually moved to Harvard University’s Houghton and Widener Libraries. What was new about Franklin Roosevelt’s creation was its codification of what is today’s presidential library system. Roosevelt convened a committee of professional historians for advice and consultation, raised the private funds necessary to build the library and museum, urged Congress to pass the enabling legislation, involved leading archive and library authorities, and ultimately deeded the site to the American people via the National Archives, which itself he had signed into being in 1934.

The academic advisors, archivists, and library professionals at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library were all important, indeed crucial, to the professionalization and growth of both the Roosevelt site and what would become the National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of Presidential Libraries. However, Roosevelt understood in those early that he also needed someone within his museum and library who knew him deeply and understood the nuances of his life and long career. That is why he turned to Ms. Suckley, securing her a position as junior archivist in September 1941 just months after the opening. The library was very much a working place for the president, who kept an office there, where—unbeknownst to museum-goers on the other side of the wall—he might be going through papers with Daisy, entertaining dignitaries while she looked on, or even making decisions of consequence to the war. Ms. Suckley worked conscientiously, even lovingly, in the presidential library, going through boxes of photographs and identifying individuals, providing dates and place names that only she would know, filling in gaps in the historical record, sorting papers, and serving in ways only an intimate could. The work only expanded after President Roosevelt died and associates like Felix Frankfurter and others donated all or some of their own papers. The work also became more institutionalized and codified. Other Roosevelt aides took on increasingly important roles after the president’s death in 1945. More series of papers became available to scholars in the 1950s and 60s as the Roosevelt Era receded from current events into history. Through it all Daisy Suckley continued on for nearly two more decades until her retirement in 1963.

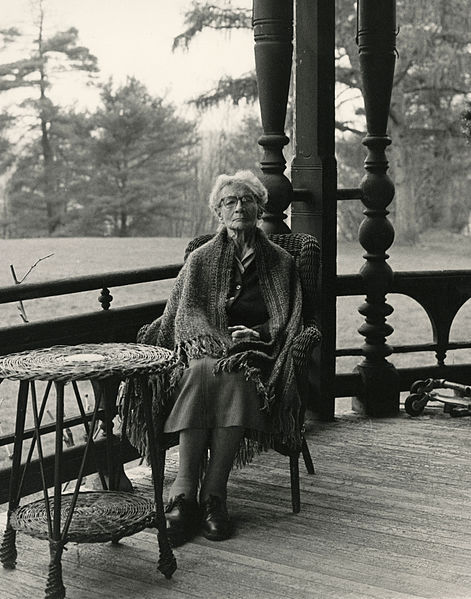

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley lived for twenty-eight more years after her retirement, turning her attention to the preservation of her ancestral home there on the Hudson but never forgetting Franklin. In those later years when reporters, historians, and the just plain curious curious showed up at Wilderstein and inevitably asked if there was any more to tell about her friendship with Franklin Roosevelt she always gave a wry smile and demure “No, of course there isn’t.” After her death at the age of ninety-nine in June 1991 however a trove of letters and diaries was found in an old suitcase hidden under her bed there at Wilderstein. A leading Roosevelt scholar edited and published a significant portion of the journals and correspondence in 1995 to great public interest. While it is still unclear if there was every any romantic involvement between Franklin and Daisy—as some have speculated for decades—the letters do provide a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of their relationship and show just how close the two were. Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have been The Sphinx to many, hiding his feelings behind a veneer of affability and bonhomie. To his old neighbor, distant cousin, discreet friend, loyal aid, and steadfast curator Margaret Suckley, he showed the truer, more vulnerable side of himself.

Ms. Suckley later in life at Wilderstein, 1988. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

Further reading:

Hufbauer, Benjamin. “The Roosevelt Presidential Library: A Shift in Commemoration.” American Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, Fall 2001, pp. 173–193.

Koch, Cynthia M. and Lynn A. Bassanese. “Roosevelt and His Library, Parts 1 & 2.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 2001, Web.

McCoy, Donald R. “The Beginnings of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library,” Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives, vol. 7, no. 3, Fall 1975, pp. 137-150.

Persico, Joseph E. Franklin & Lucy: President Roosevelt, Mrs. Rutherford, and the Other Remarkable Women in His Life. Random House, 2008.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley. Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

This post was written by Polly Thistlethwaite, Chief Librarian, The Graduate Center, City University of New York. The photo above, taken by Liz Snyder in 2013, shows BC Sellen and Polly Thistlethwaite in New Orleans.

Betty-Carol “BC” Sellen was born 1934 in Seattle, WA. She is a librarian and a collector of American folk and outsider art and author of several resource books on the subject. She attended the University of Washington for both her Bachelor’s (1956) and Master’s (1959) degrees, and she earned a second Master’s from New York University in 1974. She held positions of increasing responsibility in the profession, starting at the Brooklyn Public Library (1959-60), then with the University of Washington Law Library (1960-63), and finally at the City University of New York Brooklyn College Library from 1964 until her retirement in 1990 as Associate Librarian for Public Services. She resides in Santa Fe, NM, and also spends time in New Orleans, LA.

As a library school student at the University of Washington, Sellen engaged with student government to pressure the university to concern itself with housing for students of color, with particular focus on students from Africa who struggled to find places to live. A media campaign called attention to discriminatory city housing practices and forced the university to support students impacted by them.

Sellen’s librarianship provided a platform for wide-ranging activism, gaining particular notoriety for her work on feminist issues in the profession. Sellen was active in the founding of the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table, a co-founder and 1982-3 chair of the ALA Feminist Task Force, and chair of the Committee on the Status of Women in Librarianship following that.

With a cohort of librarian feminists, she organized an American Library Association Preconference on the Status of Women in Librarianship sponsored by the Social Responsibilities Round Table Task Force on the Status of Women in 1974 at Douglass College, Rutgers University. In the Introduction to the proceedings from that Preconference [1], Sellen describes initial meetings of the group with the incisive directness characteristic of her commentary:

Most of this first meeting was consumed by men telling the women how to improve themselves, and furthermore that what the profession really needed was more men to improve the image. In spite of these helpful suggestions and the scornful attitude of many male SRRT members, who fancied themselves a part of the macho left, where women’s issues were considered frivolous, the women were able to organize together and to become an active and notable presence at ALA conference meetings.

Sellen further explains her cohort’s librarian-focused strategies to “utilize talents and abilities already present among women librarians and not call up experts or ‘big names’ outside the profession” to build professional self-reliance in a likely long-term struggle against systemic oppression.

The preconference generated tangible results: a national survey about union types and priorities; a feminist librarian directory and support network S.H.A.R.E. (Sisters Have Resources Everywhere); a library education resolution presented to ALA membership directing the Committee on Accreditation to practice nondiscrimination in hiring and promotion of library school members; a statement to ALA regarding the Ford Foundation-funded Council on Library Resources to examine grant awarding and promotion practices; a variety of watchdog efforts directed at library schools, the library press, and professional journals; and the recommendation that a daily ‘sexist pig’ award be reported in the ALA Conference Cognotes publication with accompanying instruction about how to make nominations for it. The conference also generated resolutions presented to the ALA for deliberation during the 1974 Annual Conference Meeting in New York City involving accreditation, child care services, position evaluation, sexist terminology, support for affirmative action, terms of administrative appointment, and women in ALA Council positions.

Sellen was also active in New York City library politics. She was President of the Library Association of the City University of New York (LACUNY) [2] during the tumultuous years of 1969 – 71 and co-chair of the 1968 LACUNY Conference [3] New Directions for the City University Libraries that laid the groundwork for the CUNY union catalog and growth of the productive coalition of CUNY libraries. Sellen’s engagement with library politics around the country introduced varieties of library organization, policies, and political concerns into CUNY library activism.

Sellen was engaged in efforts to obtain and to maintain faculty status for CUNY librarians, to match the salaries, benefits, and prestige afforded other university faculty colleagues, achieved in 1965 [4]. In her role as president of the LACUNY Sellen encouraged librarians to publish in scholarly and literary journals as appropriate platforms for librarians’ work. She wrote Librarian/author: A Practical Guide on How to Get Published (Neal-Schuman, 1985) to further that concern.

Sellen was also a defender of academic freedom. When Zoia Horn, librarian at Bucknell College in Lewisburg, PA, was jailed for refusing to turn over library borrowing records regarding the Berrigan brothers (who were imprisoned for anti-American activities) [5], Sellen organized NYC fundraising to support Ms. Horn’s legal defense. [More from WoLH on Zoia Horn here–ed.]

Sellen valued collaboration and often co-authored her academic and professional work on library salaries, alternative careers, and feminist library matters. She was a prodigious author of letters-to-the-editor of library professional publications. She wrote brief, widely-read letters for American Librarians and Library Journal on topics such as librarian faculty status, the sexist underpinnings of the librarian image problem, intellectual freedom in Cuba, sexism and salary discrimination in the library profession, suppression of gay literary identities, and on unacknowledged incidents of censorship. In 1989 she criticized appointment of Fr. Timothy Healey to head the New York Public Library on the grounds that as a CUNY administrator, prior to his NYPL appointment, Healey had systematically undermined librarians and libraries. Sellen remembered publicly that Healey, in a CUNY meeting she attended, announced that “college librarians were about as deserving of faculty status as were campus elevator operators” [6], exposing a cluster of problematic biases held by a man appointed a leading NYC cultural administrator.

In the 1970s, Sellen convinced several other librarians, including Susan Vaughn, Betty Seifert, Joan Marshall, Kay Castle, to take up residence on E. 7th Street in New York City’s East Village. She resided at 248-252 East 7th St. Sellen joined with a multi-ethnic group of residents to rehab neighborhood buildings and establish them as self-governed cooperatives. Sellen was active in the same block association that battled the drug trade that flourished in the neighborhood as early as the 1970s and continued into the 1990s [7].

In 1990 Sellen received the ALA Equality Award, commending her “outstanding contributions toward promoting equality between men and women in the library profession.” The commendation recognizes her tireless labor and sustained coalition building as a leader in several landmark conferences on sex and racial equality, and her “inspiration to several generations of activist librarians.”

Sellen’s eclectic expertise was reflected in her published works. She assembled and edited The Librarian’s Cookbook (1990). She co-authored The Bottom Line Reader: A Financial Handbook for Librarians(1990);The Collection Building Reader (1992) and What Else You Can Do with a Library Degree(1997).

In her retirement, Sellen became an accomplished collector of American folk art. She authored and co-authored several reference books on the topic, including 20th Century American Folk, Self-Taught, and Outsider Art (1993) and Outsider, Self-taught, and Folk Art: Annotated Bibliography (2002) with Cynthia Johanson; Art Centers: American Studios and Galleries for Artists with Developmental or Mental Disabilities (2008); and Self-taught, Outsider and Folk Art: A Guide to American Artists, Locations, and Resources(2016).

Footnotes

1. Marshall, Joan; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1975). Women in a women’s profession: strategies: proceedings of the pre-conference on the status of women in librarianship. American Library Association.

2. Schuman, Patricia; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1970). Libraries for the 70s. Queens College, City University of New York.

3. Sellen, Betty-Carol; Karkhanis, Sharad (1968). New Directions for the City University of New York: Papers Presented at an Institute. Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York.

4. Drobnicki, John A. (2014). CUNY Librarians and Faculty Status: Past, Present, and Future. Urban Library Journal 20(1).

5. Horn, Zoia. (1995). Zoia! Memoirs of Zoia Horn, Battler for People’s Right to Know. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

6. Sellen, Betty-Carol. (June, 1989). Healy: Unequivocal Dismay. Library Journal, p. 6.

7. Pais, Josh et al. 7th Street. (2005). Video. Paradise Acres Productions.

Our final post for Women’s History Month 2017 comes again from Lorna Peterson, Emerita Associate Professor, University at Buffalo. The photo above was provided by family and printed on memorial service program and online obituaries; see The Oberlin News Tribune from Feb. 23 to Feb. 24, 2017 (accessed March 16, 2017)

Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins

February 27, 1936 - November 11, 2016

Raised on Historically Black College and University campuses (HBCUs) as well as two years in Monrovia, Liberia by her professor and diplomat father and librarian mother, influenced by a Quaker education in Iowa, and educated at a Seven Sisters college and an Ivy League university both in New York City, Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins lived an outstanding librarian career that encompassed the transitions of the United States civil rights era.

With the enactment of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, the development of public policy to implement the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 was challenged by competing philosophies of integration versus black separatism within the black community. One response to that challenge was the establishment of a consortium and research institute of social scientists called MARC, Metropolitan Applied Research Center. Founded by psychologist Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, an aim of the institute was to provide a non-partisan forum for discussion between black and white politicians at city, state, and federal levels regarding the issues, policies and programs most relevant to the officials’ constituents and communities. Central to the MARC institute and its work was the library, and the head of that library was Betty L. Jenkins. Building the collection and directing the library influenced Ms. Jenkins’s own research and publication output. Her contributions to understanding race relations in the United States, as well as in American librarianship, are unique and foundational.

Born February 27, 1936, in Harris County, Texas, to professor, college administrator, and diplomat Ralphael O’Hara Lanier and librarian Garriette Lucile Green(e) Lanier, Betty was raised on the campuses of Texas State University for Negroes (now Texas Southern University), Hampton Institute (currently Hampton University), and other HBCUs along with her younger sister, Patricia. The family lived in Monrovia Liberia from 1946-1948, where her father was U.S. Minister to Liberia.

Educated for high school at the Quaker Scattergood Friends School in West Branch, Iowa, she developed a lifelong respect for Quaker principles, although she did not become a member of the Religious Society of Friends. She began her first college year at Grinnell College in GrinnelI, Iowa, and then transferred to Barnard College in New York City, where she earned a BA degree in history. Following the baccalaureate degree, she entered and graduated from the MS program in Library Service at Columbia University and later earned a MA in American history from New York University.

As part of her duties at MARC and at the request of the Hastie Group, Betty Jenkins, along with Susan Phillis, compiled and published the annotated bibliography Black Separatism in 1976. The bibliography is organized by two parts. Part 1 concerns separatism vs. integration within a historical perspective, citing and annotating materials from 1760-1953 and then followed by the twenty years since BrownvBoard of Education. Part 2 lists citations concerning the institutional and psychological dimensions regarding identity, education, politics, economics, and worship within the context of segregation and desegregation. Works that concern redressing racial inequities are also documented in Part 2 of the bibliography.

Betty Jenkins was a bibliographer and scholar librarian who published, presented, and created exhibits that documented the black experience in America. Works by Betty Jenkins include but are not limited by the following:

• a bibliographical essay written with Donald Franklin Joyce, “Aiming to publish books within the purchasing power of a poor people”: Black-owned book publishing in the United States, 1817-1987,” Choice February 1989, vol. 26, pages 907-913;

• solo authored and groundbreaking critical race biography of Ernestine Rose: “A white librarian in black Harlem,” Library Quarterly; July 1990, Vol. 60, pages 216-231; and

•Kenneth B. Clark: A bibliography, MARC 1970, 69 pages.

With assistance from the City College of New York (CCNY) Libraries, these additional contributions by Betty Jenkins are identified:

• CCNY issue of The Campus February 19, 1991: “Leading City College Black Faculty Discuss their Progress and Achievements at CCNY,” which is based on an event partly organized by Betty Jenkins;

• Principal Investigator for a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to host a conference and create conference proceedings for “We Wish to Plead our Own Cause”: Black-Owned Book Publishing in the United States 1817-1987 held May 1988 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of NYPL;

• One of the curators of the CCNY Libraries Cohen Library Atrium exhibit “Parallel Worlds: African Americans in Harlem and Paris in the 1920s” February-June 2001.

As well as working for various libraries in the CCNY system, Betty Jenkins also worked at Howard University. Through her careful scholarship of bibliography, mounting exhibits, and writing a librarian biography within a context of race conflict and cooperation, Betty L. Jenkins preserved and interpreted the history and lives of Americans, particularly black Americans.

References

Ancestry.com. Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data: Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997. Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services. Microfiche.

Obituary of Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins of Oberlin Ohio, Dicken Funeral Home

Today’s #UrbanExploration post concerns the building known as the Piano Factory aka the Sohmer & Co. Piano factory building on Vernon Boulevard and 31st Avenue in Astoria, New York.

Built in 1866, the building was built in the Romanesque Revival style with a two sided clock tower corner and a copper trimmed mansard roof.

The building was the home of the Sohmer & Co. Piano factory for over a decade. In 1982 the company moved its operations to Ivoryton, Connecticut. For the next couple of decades, the building’s ownership changed hands multiple times. In 2007 the building earned landmark status number 2172 courtesy of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The building is now a residential building.

#UrbExNYC #SohmerAndCompany #SohmerAndCompanyPianoFactory #ThePianoFactory #ArchitecturalHistory #EngineeringHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #AstoriaHistory #QueensHistory #AmericanHistory #USHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco

https://www.instagram.com/p/CdJTBlUun8u/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

Post link

Today’s #UrbanExploration post takes us to the Financial District to the building known as 1 Wall Street Court aka the Beaver Building aka the Cocoa Exchange aka to John Wick fans as The Continental Hotel.

The building was designed by Clinton and Russell in the Renaissance Revival style and was completed in 1904. Tenants included the The building served as the headquarters of the Munson Steamship Line Company from 1904 until 1921 and the New York Cocoa Exchange from 1931 to 1972.

The building became a NYC in 1995 by being recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 2005. In 2006 it was converted to residential condominiums.

#1WallStreetCourt #BeaverBuilding #NewYorkCocoaExchange #JohnWick #TheContinentalHotel #ArchitecturalHistory #EngineeringHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #AmericanHistory #USHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco (at 1 Wall Street Court)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CcZF1ncuGuS/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

Post link

I love it when old signs that are painted on a building reappear when a building gets torn down/renovated. This sign for a Studebaker auto dealership still has its bright blue color. On Fordham Road between Cambreleng and Belmont Avenues.

#OldSigns #Studebaker #Bronx #BronxHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #AutomotiveHistory #AmericanHistory #USHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco (at Fordham Road NYC)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CeZaBkROu8u/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

Post link

Today #UrbExNYC post comes from the County of Kings in the form of the iconic Coney Island landmark Nathan’s Famous, on the corner of Stillwell and Surf Avenues.

Polish immigrant Nathan Handwerker opened his first nickle hotdog stand in 1916 and the original stand has expanded to the location you see here. As of 2019, Nathan’s had 213 locations worldwide.

#NathansFamous #NathanHandwerker #UrbanExploration #BrooklynHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #CulinaryHistory #FoodHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco (at Nathan’s Famous)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CdytRZEu47w/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

Post link

December 4, 1783 - Washington bids farewell to his officers

“On this day in 1783, future President George Washington, then commanding general of the Continental Army, summons his military officers to Fraunces Tavern in New York City to inform them that he will be resigning his commission and returning to civilian life.

Washington had led the army through six long years of war against the British before the American forces finally prevailed at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. There, Washington received the formal surrender of British General Lord Charles Cornwallis, effectively ending the Revolutionary War, although it took almost two more years to conclude a peace treaty and slightly longer for all British troops to leave New York.

Although Washington had often during the war privately lamented the sorry state of his largely undisciplined and unhealthy troops and the ineffectiveness of most of his officer corps, he expressed genuine appreciation for his brotherhood of soldiers on this day in 1783. Observers of the intimate scene at Fraunces Tavern described Washington as “suffused in tears,” embracing his officers one by one after issuing his farewell. Washington left the tavern for Annapolis, Maryland, where he officially resigned his commission on December 23. He then returned to his beloved estate at Mount Vernon, Virginia, where he planned to live out his days as a gentleman farmer.

Washington was not out of the public spotlight for long, however. In 1789, he was coaxed out of retirement and elected as the first president of the United States, a position he held until 1797.”

This week in History:

December 1, 1955 - Rosa Parks ignites bus boycott

December 2, 1823 - Monroe Doctrine declared

December 3, 1818 - Illinois becomes the 21st state

December 4, 1872 - The Mystery of the Mary Celeste

December 5, 1933 - Prohibition ends

December 6, 1884 - Washington Monument completed

December 7, 1941 - Pearl Harbor bombed

Thiscolor lithograph depicting Washington’s farewell to officers can be found in the online collection of the Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Post link