#black history month

Dr. Minnie Joycelyn Elders is an army veteran, pediatric endocrinologist, and public health administrator who was appointed the first African American Surgeon General of the United States by Bill Clinton in 1993.

Her outspoken views on female reproductive rights and science-based sex education in high schools made her a controversial public figure, prompting massive backlash from conservative parties of the time.

After her resignation as Surgeon General in 1994, Elders returned to her former position as professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences where she is currently a professor emeritus and remains active in public health education.

You can learn more about Dr. Elders in her 1996 autobiography, Joycelyn Elders, M.D.: From Sharecropper’s Daughter to Surgeon General of the United States of America.

Hey all! It’s February which means it’s time for our annual #BlackHistoryMonth scientist highlights!

.

Check back routinely to learn more about the wonderful contributions made by black scientists!

.

To start us off, meet Dr. Joan Murrell Owens, a scientist, educator, and marine biology enthusiast! Pursuing her passion for the ocean, Dr. Murrell investigated different coral species, specifically deep-sea button coral. Working at the Smithsonian, Joan identified a new family of corals, the Rhombopsammia genus, and discovered three new button coral species.

Matt Baker - one of the first successful black comic book artists in the early 1940s and 50s.

Post link

Madam C.J Walker - she created a line of black hair care products and was one of the first black woman to become a self-made millionaire in the early 1900s.

Post link

Henrietta Lacks - Her cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, the first immortalized human cell line. (Her cells were taken and used without her consent)

Post link

Bryan Stevenson on Black achievement and progress

Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, speaks with Lester Holt about Black achievement and how far the needle has moved toward equality and acceptance.Click here for an extended interview.

Two generations of Black athletes fight for change:

NBC News’ Morgan Radford speaks with Olympian John Carlos and WNBA star Nneka Ogwumike about their calls for justice more than half a century apart.

I never thought that I would write a love letter to someone other than my bae, on Valentine’s day, yet here we are. It’s only right, as during this series I am gushing over those that came before me that I say hello, hi and thank you so ever much to the Lady Of Soul.

Jenny Francis was at the helm of Choice FM for most of my life, it is no surprise that hers was the longest running…

Trisha Goddard Changed My Life

Life wasn’t the same after 2004, before then you could count on Trisha. Every weekday morning, rain or shine, she would be there. Helping people find their long lost family members, finding out who stole the money from nan’s purse or even helping those who have had their hearts broken learn to love again.

You knew what you were getting with Trisha.

One of my fondest memories was is of me sipping…

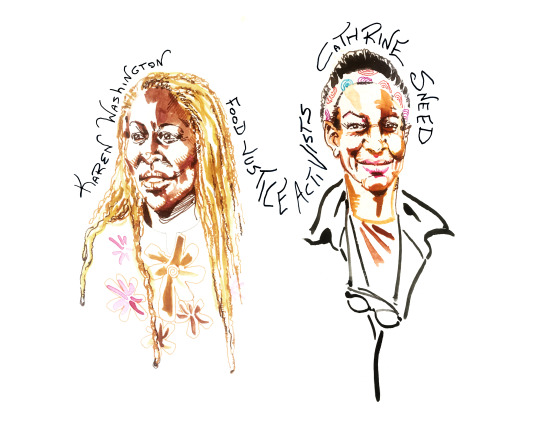

Credit:George McCalman

“Food should be a right for all and not a privilege for some.”

— Karen Washington

Fresh food should not be out of reach due to racism.

As a physical therapist, lifelong NYC resident Karen Washington is more in tune with the needs of the body than most. In the early years of her practice, she noticed some of her clients were struggling with what she calls the “three food groups — fast, junk and processed.”

Washington spotted a vacant lot across the street from her Bronx home, where she’d already planted a backyard garden. She transformed the lot into the Garden of Happiness in 1988 and her journey into community gardening began.

All around the Bronx, Washington and her neighbors found throwaway spaces and turned them into gardens, eventually founding a farmer’s market. When Mayor Giuliani tried to wipe away their work in the ‘90s, Washington and other activists resisted, drawing on civil disobedience tactics — and they succeeded.

On the left, Karen Washington receives a 2010 National Medal for Museum and Library Service along with Gregory Long, director of the New York Botanical Garden, from First Lady Michelle Obama at the White House. Pictured to the right, Washington with her tools.

Their work laid a template for a broader urban ag movement, but for Washington community gardening is first and foremost about social justice. To continue her journey in urban farming, Washington attended UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems (CASFS) apprenticeship program in 2008. The “mothership of organic agricultural training,” in the words of executive director David Press, CASFS teaches cutting-edge techniques for healthy, sustainable food, and the education, in the words of Washington, was a “gift.”

Returning to New York, Washington not only co-founded Black Urban Growers, a volunteer-driven support network, but sought to replicate her experience at UC Santa Cruz.

“We found a lot of people couldn’t get to California, so we replicated a sort of CASFS program in NYC,” Washington said. Her Farm School NYC focuses on community-based activism and farming to encourage residents of low-income neighborhoods to embrace food sovereignty and disrupt a food system that does not serve them well — if at all.

While black households disproportionately struggle from food insecurity (1 in 4 experience food insecurity, compared to 1 in 7 overall and 1 in 10 white households) for those recently released from prison, food insecurity is nearly a guarantee — 90 percent report experiencing it. The need to feed your family can drive people to desperate measures, as Cathrine Sneed of the Garden Project knows well.

“In my 20-year history, I have spoken to too many young men who said ‘I started selling drugs because my momma couldn’t feed me, and I was hungry.‘”

— Cathrine Sneed

“In my 20-year history, I have spoken to too many young men who said ‘I started selling drugs because my momma couldn’t feed me, and I was hungry,'” Sneed says of her work in urban gardening. A fresh young law school graduate, Sneed landed in San Francisco County Jail as a counselor, focused on helping prisoners live successful lives once released outside. But she found it wasn’t so easy to break the cycle of recidivism — they walk into the world with no money, no job, no home, and no food.

Sneed couldn’t fix all these issues — but she could lead prisoners outside, onto the jail grounds, to work on land that had once been a farm. Her wish was that they could derive hope from a connection with the land and by providing food for the community. Her results surpassed her wildest dreams.

Cathrine Sneed, left, keynote speaker for the 2014 Farm to Fork event at the UC Santa Cruz at the Center for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems (CASFS). Photo by Melissa De Witte.

In 1992, Sneed, another former UC Santa Cruz CASFS apprentice, began the Garden Project to meet the demand of former inmates connected to the work. The scope of the project expanded to include counseling, continuing education assistance and job training. The Garden Project has planted over 10,000 trees in San Francisco — and has cut the recidivism rate, nationally at 50 percent after two years on the outside, to 25 percent for its participants.

Sneed has now extended the program to at-risk adults and high school students, to break the cycle before it starts. “Gardening is the recipe for success,” said Sneed of the work. “This is how we stop crime.” Thanks to these two women, urban gardening is also a recipe for community empowerment, and longer, healthier lives.

Credit:George McCalman

The content we consume and its authenticity are called into question on a daily basis. But just 50 years ago, this was far from a common way to engage with art, culture and literature. That all changed with Barbara Christian.

From a young age, Christian was an avid reader, questioning why there were no African American or Afro Caribbean women included in the books she read. Born and raised in the U.S. Virgin Islands, she dedicated her life to changing ideas about race, gender and class, particularly around the representation of black women in American literature, ultimately asking, “who gets to tell their stories?”

While pursuing a graduate degree in literature at Columbia University, Christian became friends with Langston Hughes and was introduced to the works of many black writers. Her exploration of these writings would be realized later in her career — she was one of the first scholars to bring the works of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker to the attention of academia.

In 1972, two years after graduating from Columbia, Christian became an assistant professor at UC Berkeley. She was pivotal in creating the university’s African American studies department and, in 1978, was the first African American to be granted tenure. “She was a path-breaking scholar,” said Percy Hintzen, chair of the UC Berkeley department of African American studies. "Nobody did more to bring black women writers into academic and popular recognition.”

For so long, the majority of representations of black women in literature were crafted by white writers. Christian wanted to change that. Her theories provided a foundation for black women to assert control over their own image in American literature. Her 1980 study, “Black Women Novelists: The Development of a Tradition,” was the first of its kind to look at black feminist literature from the nineteenth century to contemporary times. In her lifetime, Christian truly pioneered the birth of black women’s literary criticism and theory.

“I can only speak for myself. But when I write and how I write is done in order to save my own life. And I mean that literally,” she noted. “For me literature is a way of knowing that I am not hallucinating, that whatever I feel/know is.”

Credit:George McCalman

“First, do no harm.”

In the 1980s, the medical establishment didn’t always heed this call when it came to HIV/AIDS.

HIV/AIDS may be manageable now, but in the early days it was a mystery and often ignored, as it primarily affected gay men and was accompanied by stigma and shame. Many doctors and medical administrators stood by as the disease took its toll. Eric Goosby was one of the pioneers who shed light and provided much-needed treatment.

The fight against HIV/AIDS has consumed Goosby’s entire career, and millions of lives have been bettered thanks to the intensity of his commitment. Goosby received his M.D. in 1978 from UCSF, completing his residency there in 1981 — the first year AIDS was clinically observed by UCLA doctor Michael Gottlieb. By the time his fellowship at UCSF ended in 1983, San Francisco was in a full-blown crisis, and Goosby was on the front lines, a member of the revolutionary Ward 86, the first dedicated AIDS clinic in the country.

Credit: UCSF

Figuring out the nature of the crisis, while trying to treat it, absorbed the doctors of Ward 86, who developed the “San Francisco Model” of care: a patient-centered collaboration with a wide network of carers, including social workers, mental health care providers, addiction specialists and community organizers. This model has become the standard of care around the world. Goosby focused on establishing partnerships with methadone maintenance clinics to help addicts obtain HIV services, as IV users were less likely to seek treatment and the black community was overrepresented among injection drug users.

Even as Goosby and Ward 86 attacked AIDS on multiple fronts, patients were slipping away. Goosby and the other doctors fell into despair during therapeutic group sessions and struggled to maintain their personal relationships. The fight was further complicated by a lack of response from the federal government, who ignored the epidemic for many years. There wasn’t funding for research, education or treatment programs for this national health crisis. In cities that weren’t using the “San Francisco Model,” those with HIV/AIDS were suffering, especially patients from marginalized communities that were being misdiagnosed and poorly served.

Dr. Eric Goosby, U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, gives his perspective on 30 years of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. Credit: HIV.gov

Fed up with inaction, and having lost his 500th patient, Goosby moved to Washington, D.C., in 1991 to direct HIV Services at the Health and Human Services Department, spreading the approach of the San Francisco Model throughout the country. Even as he took on this important federal role, he practiced part-time in an AIDS clinic in the city’s public hospital, D.C. General. As an administrator, he brought funding and services to 25 AIDS epicenters and to all 50 states and U.S. territories, and rose up the ladder to become director of the health department’s office of HIV/AIDS policy. He later became President Clinton’s senior advisor on HIV-related issues and helped initiate a dialogue on racial disparities in HIV/AIDS that formed the basis of the Minority AIDS Initiative.

As treatment slowly began to advance in the U.S., Goosby turned his attention to the rest of the world, where poorer nations, in particular, were finding themselves devastated by the disease. After working on scaling up treatment in Rwanda, South Africa, China and Ukraine as CEO of Pangaea Global AIDS Foundation, Goosby was nominated by President Obama to serve as the U.S. global AIDS coordinator and administer the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (Pepfar), a $48 billion program credited with cutting AIDS deaths by 10 percent in some countries.

The remarkable career of Eric Goosby has no end in sight. In addition to serving as the U.N. special envoy for tuberculosis, Goosby is a professor of medicine at UCSF. And, of course, he returned to care for patients at Ward 86, which continues to provide treatment and set standards for prevention and care around the world.

“It’s just something that is almost like breathing to me. I love practicing medicine; I love helping people in that way; I like using my mind in that way; maybe I love pushing people around; maybe I love telling people what to do. I don’t know what it is, but I cannot imagine not doctoring.”

Credit:George McCalman

Ava DuVernay is a force in Hollywood, having made a name for herself not only as a director, producer and screenwriter, but as a champion of change. Now, more than ever, media representations that we see daily in print, on television, and in films are being called into question. But, for the past decade, Ava DuVernay’s mission has been to push for more inclusivity on sets and on screen. “Diversity is not just a box to check. It’s a reality that should be deeply felt and held and valued by all of us,” DuVernay said in an interview with Fast Company.

How did DuVernay become a Hollywood game changer?

Her story isn’t a straight line — it’s a series of pivots based on strong determination and the willingness to take chances to forge her own path. Born in Long Beach, California, DuVernay was raised in a matriarchal environment with lots of women who always encouraged her to follow her heart. She grew up near the Compton neighborhood of Los Angeles and was the first African American student body president at her high school. Film wasn’t her dream from the get-go. As an undergrad at UCLA, she pursued a major in African American studies, then shifted into the world of public relations after spending time as a journalist.

Ava DuVernay gave the commencement speech at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television in 2017. Photo credit: UCLA

At 27, she started her own public relations firm, The DuVernay Agency. As a film publicist, she was able to get close to different filmmakers, seeing how movies were made firsthand. This proximity to the world of film enamored her. While on a film set in East Los Angeles for the 2004 crime thriller, “Collateral,” DuVernay had an aha! moment when she realized that she wanted to be the one telling the stories, the one making the movies. “Javier Bardem was on set, and something about the scene with Javier and Jamie, this brown man and this black man: It was this gritty place in East L.A. at night, with a digital camera, and I just loved it,” she shared with Rolling Stone. “I started writing a script that weekend.“

In 2011, she self-financed “I Will Follow,” her first feature film she wrote and directed, after a few years of learning the film trade while working on shorts and documentaries. Just three years later, she directed the acclaimed “Selma,” a film about Martin Luther King Jr. and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march. Following the release of “Selma,”DuVernay was the first African American female director to be nominated for an Academy Award for best picture. With the upcoming release of “A Wrinkle in Time,” boasting a budget exceeding $100 million, DuVernay is now the first African American woman to direct a live-action film with a budget of that size.

Ava DuVernay on her journey to become the first black woman to direct an Oscar nominated film. Credit: TIME

Beyond her notable accomplishments and series of “firsts,” she’s hoping to create a larger shift in Hollywood, one with varied voices and stories in cinema. Just three years ago, she expanded her film distribution company to become ARRAY, where female filmmakers and people of color are at the forefront. “It comes down to who gets to tell the story? If the dominant images that we have seen throughout our lifetime, our mother’s lifetime, our grandmother’s lifetime, have been dominated by one kind of person, and we take that, we internalize it, we drink it in as true, as fact. It’s tragic,” DuVernay wrote in Timemagazine. “It goes beyond the film industry. These are the images of ourselves we consume. It affects the way we see ourselves and the way other people see us.”

The world of film in the United States has been built and defined by the predominately white patriarchy. But with her courageous streak and fearless creativity, DuVernay is opening doors for women, people of color and those who have been underrepresented in the film industry for so long. By advocating for a diverse set of at least 50 percent people of color and women, DuVernay has put her own politics in action: “Inclusion is really half — half of the cast, half of the directors, half of the writers are women or girls, half of the room, more than half of the room is of color,” she shared with Ellemagazine. “I think we get really satisfied with less.” And she’s just getting started. For “A Wrinkle in Time,” DuVernay warned the each of the department heads on her crew not to submit the same list of hires unless they could prove they had considered others. In making inclusion a key nonnegotiable in her creative process, DuVernay is changing the narrative for how stories are told and who gets to tell them.

Credit:George McCalman

Hysteria. The vapors. Penis envy. Homosexuality as a disease. Dementia praecox.

There’s no shortage of outmoded or discredited theories in the field of psychology. For the late Joseph White, professor of psychology and comparative culture at UC Irvine and “godfather of black psychology,” the most pressing issue in the field in the late ‘60s and 70s was the representation of African Americans — or lack thereof.

“It is vitally important that we develop, out of the authentic experience of black people in this country, an accurate workable theory of black psychology,” wrote White in his groundbreaking Ebony piece “Toward a Black Psychology.”

His argument was not simply that notions of black inferiority — a predisposition to a lower IQ, for example — were wrong, but that the way psychology evaluated mental health and development, particularly in poorer neighborhoods, was based on biased frameworks that perceived only deficiency, not difference, and invalidated the lived experience of its subjects.

Joseph L. White speaks to students at UC Irvine in 2013.

White critiques, for example, the white researcher who enters a home looking for a copy of the New York Review of Books as evidence of of an intellectually stimulating environment when a black preschooler is nearby reciting several songs from memory. He also takes researchers to task for their reduction of black family life to a series of deficiencies — family unit with a missing father — when a highly engaged extended family often plays a substantive role in the development of a child. And he writes that certain attitudes cherished by white culture do not hold the same significance in black culture because their outcomes are not the same — a dynamic we see in today’s racially divergent perceptions of law enforcement.

A strike against cultural deprivation theory, White argued for a strength, not deficit, based psychology.

Joseph L. White, UCI professor emeritus of social sciences, is known as the “father of black psychology.“ Steve Zylius / UC Irvine.

White’s piece cemented his status as a pioneer, a role to which he was no stranger. White was only one of five black Ph.D.s in psychology when he earned his doctorate in 1961. He became one of the founders of the Association of Black Psychologists in 1968 and produced “Toward a Black Psychology” in 1970, while at UC Irvine.

In addition to paving the way for a multicultural psychology, White was also committed to mentorship, establishing the Educational Opportunity Program, which has provided access for more than 250,000 disadvantaged students in California, many of them the first in their family to college. He personally mentored more than 100 students who went on to become psychologists from diverse backgrounds — African American, Asian American, Latino, Native American and women.

White passed away in late 2017, but leaves behind a legacy from a remarkable life — he was a campaign director for Robert F. Kennedy (!) — and a field, psychology, far more sensitive and inclusive than when he found it.

Credit:George McCalman

Ralph Bunche was a man of many firsts. He was the first African-American valedictorian at UCLA. The first African-American in the country to receive a Ph.D. in political science. And the first African-American to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Bunche is considered the “Father of Peacekeeping” for negotiating an end to the first Arab-Israeli war while working at the United Nations.

In 1949, Bunche stood in his hotel room on the Greek island of Rhodes with members of the Israeli delegation and the Egyptian delegation. These were two groups of people, in a room together, that hadn’t been able to reach a resolution over the control of Palestine in more than 30 years. Now, in the midst of the first Arab-Israeli war, Bunche had been sent by the United Nations to end the conflict. He knew it wouldn’t be easy, but was determined to find a resolution.

Ralph J. Bunche shaking hands with Louise Ridgle White, future Los Angeles Assemblywoman candidate. Credit: Rolland J. Curtis, Rolland J. Curtis Collection of Negatives and Photographs/Los Angeles Public Library

How did Bunche crack the code on making peace? To understand his impact, we have to rewind a bit. Born to humble beginnings in Detroit, Michigan, Bunche was raised by his grandmother after his parents passed away. Early on, it was clear he was someone to watch. In high school, he was known as an expert debater and was named his class valedictorian. In 1923, he enrolled at UCLA, supporting himself with an athletic scholarship and a janitorial job. Bunche graduated in 1927, with a degree in international relations, and was once again the class valedictorian.

His graduation speech revealed glimpses of the career he would have as a peacemaker: “The future peace and harmony of the world are contingent upon the ability, yours and mine, to affect a remedy.”

Ralph J. Bunche, UCLA portrait. June 1927.

Credit: UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library

There was no stopping him. He went on to Harvard for graduate studies in political science, and from there he taught at both Howard and Harvard. While at Howard, he became one of the leaders of a group of Black intellectuals known as the “Young Turks.” The Young Turks’ perspective on race set them apart. They argued that issues of “class, not race” were key to solving the so-called “Negro problem.” This line of thinking was later adopted by the civil rights activists of the 1960s, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

In a shift away from the world of academia, he joined the U.S. State Department as an advisor on the future of colonial territories in 1944. Two years later, Bunche was at the U.N. From June of 1947 to August of 1949, he worked on the assignment that would serve as a defining moment in his history and the world’s: the confrontation between Arabs and Jews in Palestine.

Acting U.N. mediator, Ralph J. Bunche, in Palestine, 1948.

Credit: UC Library: A Centenary Celebration of Ralph J. Bunche

In 1949, peacekeeping was a very new concept and Bunche was determined to show that it wasn’t just a fad adopted by the U.N. – he wanted to prove it had long-lasting power. While he stood in his bedroom in Rhodes, with members of both the Israeli delegation and the Egyptian delegation, he revealed two sets of memorial plates bearing the name of each negotiator. He told the negotiators that once they signed the armistice agreement, they’d each get one of the plates as a souvenir. But if they didn’t reach an agreement, he’d break the plates over their heads. He was met with laughter from both sides, but ultimately his plan worked – they signed the agreement.

Ralph Bunche speaks on world peace at the meeting of American Association for the United Nations in Los Angeles, 1951. Credit: CriticalPast

His achievement in reaching the 1949 armistice agreement was the reason he received the Nobel Peace Prize a year later. Though they were original, the plates weren’t his secret ingredient for peacekeeping. Bunche believed there was no human problem that couldn’t be eventually be solved. He had great empathy and was interested in improving the lives of ordinary people. According to Sir Brian Urquhart, former Undersecretary General at the U.N. and one of Bunche’s colleagues, Bunche was an incredibly good listener. All these traits, along with his own unique creativity and humor, truly made him the Father of Peacekeeping, and his pioneering methods are still used by the U.N. today.

Ralph J. Bunche and Charles E. Young in front of Bunche Hall, UCLA 1969.

Credit: UC Library: A Centenary Celebration of Ralph J. Bunche

Barbara Howard, February 1938

Barbara Howard was once among the fastest women in the world and the first black woman to represent Canada on the international sports stage. At the age of 17, while still a student at Britannia High School, Howard qualified for the 1938 British Empire Games by sprinting 100 yards in 11.2 seconds, a tenth of a second faster than the Games’ record.

After a month-long voyage to get to the games in Sidney, Howard drew much attention from the Australian media and sports fans, according to the Globe:

Barbara Howard, dusky sprinter from B.C., caused quite a stir among Sydney’s populace during her appearance at the Empire games … She apparently was quite a novelty … appearing on the front page of every newspaper. They seldom see colored athletes down there … the photographers and autograph seekers kept on her trail.

Howard placed sixth in the 100 yard dash, but helped bring home silver and bronze medals in two relay races. She felt she let down Canada, so never made a big deal out of the Games when she got home. “I didn’t think I did well,“ she said. “It was nothing to be boasting about if I didn’t get the gold medal.” Her plan was to redeem herself at the 1940 Olympics, but those hopes died because the world was at war and the Games were cancelled. With her sports career behind her, Howard completed the teaching program at UBC and became the first visible minority hired by the Vancouver School Board.

Only recently has Barbara Howard’s pioneering role in sports been recognized. Last month, at the age of 92, she was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame. She is also depicted in a mural commemorating the centenary of her old high school and was awarded the "Freedom of the Municipality” by Belcarra, where she lived for years.

There has been speculation that Howard might be related to Olympians Valerie and Harry Jerome. Maybe, maybe not, but there is definitely one other fleet-footed person in her family. Barbara Howard’s uncle was Elijah “Lige” Scurry, a local lacrosse legend in the 1890s, when it was the most popular sport around. Lige was so fast on the field that Victoria and New Westminster joined forces to impose a “colour bar” on the league, which effectively ended the lacrosse career of the Vancouver team’s best player. For both Lige Scurry and his niece, the journey to their full athletic potential was cut short by circumstances beyond their control.

For more on Barbara Howard, see Tom Hawthorn’s blog. Thanks to John Burwood for spotting the link between Barbara Howard and Elijah Scurry.

Source: City of Vancouver Archives #371-1643

RIP Barbara Howard.

Post link

On January 28, 1856, Margaret Garner, her husband Robert, their four children, and approximately 11 other enslaved people crossed the frozen Ohio River. The Garners sought shelter in Margaret’s uncle’s home along Mill Creek. While in hiding, Margaret’s uncle, worried about how to keep the family safe, left his home to consult with Cincinnati abolitionist Levi Coffin.

Before his return home, U.S. Marshals and slave catchers surrounded and ultimately stormed the home. Faced with seeing her children returned to slavery, Margaret ended her two year old’s life just before being apprehended.

Margaret was held for trial in Cincinnati and abolitionists from across the country came to support her. Abolitionist Lucy Stone spoke at her trial stating, “If in her deep maternal love she felt the impulse to send her child back to God, to save it from coming woe, who shall say she had no right not to do so?”

Margaret was returned to slavery. When Ohio authorities got a warrant for Garner to try her for murder, they were unable to find her. She and her husband, Robert, died in 1858 of typhoid fever in Mississippi. Garner’s story inspired Nobel Prize-winner Toni Morrison’s novel “Beloved”.

See this image and more of Cincinnati’s Black history in CHPL’s Digital Library:

Post link