#desegregation

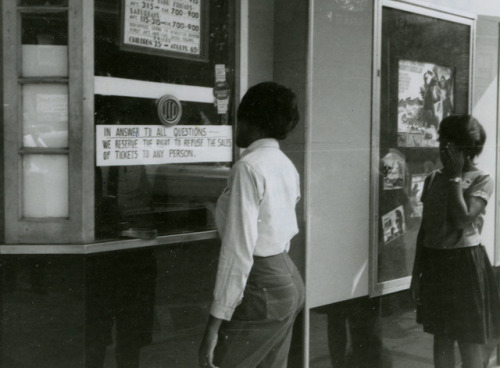

Protesting segregation at the State Theater in Farmville, Virginia, 1963

A police photographer records the actions of student protesters attempting to purchase tickets to King Kong vs. Godzilla at the whites-only State Theater. Some students hid their faces to thwart the evidence gathering, while others, like Darwyn White, smiled a challenge.

State Theater Protest photographs from the VCU Libraries’ Freedom Now Project.

On May 17, 1954 the Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education: “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” Change would come too slowly, but the decision was a landmark for the nation.

VCU Libraries Freedom Now Project gives you the opportunity to explore photographs from one Virginia county’s response to Brown v. Board of Education.

Post link

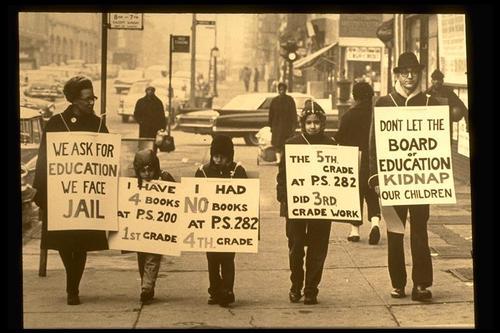

This photograph from the Brooklyn Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) collection shows the Bibuld family: parents Elaine and Jerome, and their three children Melanie, Carrington, and Douglass (L to R).

The Bibulds, an interracial family, lived in Crown Heights in the early 1960s and the children attended a neighborhood school that had a Gifted and Talented program and enrichments like art, music, and field trips. After their home caught fire in the fall of 1962, the Bibulds moved to Park Slope, and the children’s new neighborhood school had substandard academics and few enrichments — and the student body was more than 70% African American and Puerto Rican.

Elaine and Jerry Bibuld, both members of the Brooklyn chapter of CORE, were angered by this educational inequity and concerned for their children who were very bored at their new school. So, they pulled their children out of this racially segregated public school and sat them in an all-white school in the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn. Technically, the children were not enrolled in school and the City considered them truants, which opened the parents up to imprisonment for parental neglect. For roughly three months, the Bibuld protest was the most important desegregation case in the city.

(viaBrooklyn History)

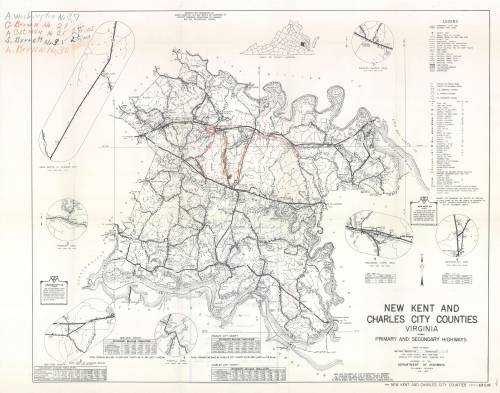

Pictured here is an annotated map of busing routes for George W. Watkins School, which was used as an exhibit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division Case Green v. New Kent County. The decision of the United States Supreme Court to desegregate schools in the 1954 landmark case Brown v. Board of Education was just the beginning of the desegregation fight. In order to meet the provisions outlined by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, while also avoiding integrating white and black school populations, many schools implemented “freedom of choice” plans. These plans did not explicitly prevent black students from attending a white school, or vice versa, but it put the responsibility of integration on the student and their family. “freedom of choice” plans placed institutional hurdles and reinforced social stigma against integrating black and white schools, which effectively halted desegregation efforts in the South.

In 1965, parents in New Kent County, Virginia, complained that the school district was deliberately maintaining a segregated school system after Brown v. Board of Education. They brought their case to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division where the court upheld New Kent Court’s “freedom of choice” plan. The case was then brought to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which affirmed the lower court’s decision (though it returned the case to the lower court for a more specific plan to desegregate teachers).

The case made it to the Supreme Court in 1968, which reversed the lower court rulings. The Supreme Court stated that the New Kent district was deliberately maintaining a segregated system and that “freedom of choice” was not sufficient to bring about desegregation. Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., writing for a unanimous court, declared: “It is incumbent upon the school board to establish that its proposed plan promises meaningful and immediate progress toward disestablishing state-imposed segregation.”

Educators and parents can review documents and create activities for students by visiting DocsTeach, which features digitized records from all three cases, as well as contextual information to help students learn more about this topic: https://www.docsteach.org/documents?filter_searchterm=Green+County+School+Board+New+Kent+County&searchType=all&filterEras=&filterDocTypes=&sortby=date&filter_order=&filter_order_Dir=&rt=cthCC3zZbaWv&reset=1

You can also learn more by visiting our online catalog (catalog.archives.gov) and reviewing digitized documents from each case.

Post link

God, anyone else remember when everyone understood that the correct feminist position about sports was that women should be allowed to compete with men because they’re just as capable? When it was a trope in media to have the mysterious star athlete who just blew everyone else out of the water to take off her helmet and reveal that she was a woman the whole time?

Now people are rabidly arguing that supposed “men” (trans women) have inherent insurmountable biological advantages and cis women are too weak and dainty and unskilled to ever compete and must be protected, and then they try to call themselves feminists who are being silenced as if that’s not just the mainstream sexist patriarchal opinion

Anyway, desegregate sports. There was never any reason to separate them by gender in the first place

November 14th…Ruby Nell Bridges Hall

On This Day in Herstory, November 14th 1960, Ruby Nell Bridges Hall an American civil rights activist, became the first Black child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis.

Ruby Nell Bridges Hall was born on September 8th 1954 in Tylertown, Mississippi, the eldest of Abon and Lucille Bridges’ five children. She was born at the height of the Civil Rights Movement; only three months before she was born Brown v. Board of Education was decided, declaring the process segregating schools unconstitutional. Despite this ruling many southern states were extremely resistant to integration. Even though it was a federal ruling, many southern state governments were not enforcing the new laws, and this allowed many white schools to remain segregated for years. Eventually, significant pressure from the federal government forced schools to integrate.

When Ruby was four years old, she and her family moved to New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1959 she attended a segregated kindergarten, but at this time the Orleans Parish School Board was forced by the federal government to take steps towards integration. The school board administered an entrance exam to students at Ruby’s school with the intention to keep Black children out of their white schools. Ruby was one of the six Black children in New Orleans to pass the test, which determined they were eligible to attend the all-white William Frantz Elementary School. Initially Ruby’s father was reluctant to send her to the school, but her mother knew that this was a necessary step not just for Ruby’s education, but to “take this step forward…for all African-American children”.

The court order that the first day of integrated schools in New Orleans was on Monday, November 14, 1960. Two of the original six children decided to stay at their old school, and three children were transferred to McDonogh No. 19. So at just six years old, Ruby went to William Frantz Elementary all by herself. On her first day she was escorted by four federal marshals and her mother; the marshals were needed to escort Ruby for her first entire school year. She later described her first day saying, “Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras.” One of her marshals later said, “She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn’t whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we’re all very very proud of her.” The same day that Ruby started at William Frantz Elementary, white parents pulled their children out of the school. All of the school’s teachers, with the exception of one person, refused to teach while a Black child was enrolled. Only Barbara Henry, from Boston, Massachusetts, agreed to teach Ruby, and for a year she taught her alone, “as if she were teaching a whole class.”

Eventually, the protests began to subside and the white children returned to school, despite this, Ruby remained the only child in her class, for an entire school year. Even though the protests wound down, for the entirety of her first year at William Frantz Elementary, every morning as she walked in one woman threatened to poison Ruby, while another woman held up a Black doll in a coffin. As a result, the marshals only allowed Ruby to eat the food she had brought from home. Unfortunately, Ruby’s entire family initially suffered for their role in the school’s integration; her father lost his job as a gas station attendant; the grocery store where they shopped no longer let them shop there; her grandparents, who were sharecroppers in Mississippi, were turned off their land; and her parents separated. However, many other people in their community showed support for the Bridges in other ways. Some white families continued to send their children to Frantz despite the protests, a neighbor provided her father with a new job, and local people babysat for Ruby’s siblings, watched the house as protectors, and walked behind the federal marshals’ car on the trips to school. Much later in life Ruby learned that even the immaculate clothing she wore to school in those first weeks were sent to her family by an acquaintance of the family.

Today, Ruby still lives in New Orleans with her husband, Malcolm Hall, and their four sons. After she graduated from a desegregated high school, she worked as a travel agent for 15 years and eventually became a stay-at-home parent. Now she is the chair of the Ruby Bridges Foundation, which she formed in 1999 to promote “the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences”. She says the mission of the group is, “racism is a grown-up disease and we must stop using our children to spread it.”

Ruby is the subject of a 1964 painting, The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell. Her book, Through My Eyes won the Carter G. Woodson Book Award in 2000. On January 8, 2001, she was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton. Unfortunately, like many other, Ruby lost her home during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Katrina also greatly damaged William Frantz Elementary School, and Ruby was instrumental in fighting for the school to remain open. On July 15th 2011, she met with President Barack Obama at the White House. Together they viewed the Norman Rockwell painting of her on display, and he told her, “I think it’s fair to say that if it hadn’t been for you guys, I might not be here and we wouldn’t be looking at this together”. In 2014, a statue of Ruby was unveiled in the courtyard of William Frantz Elementary School.

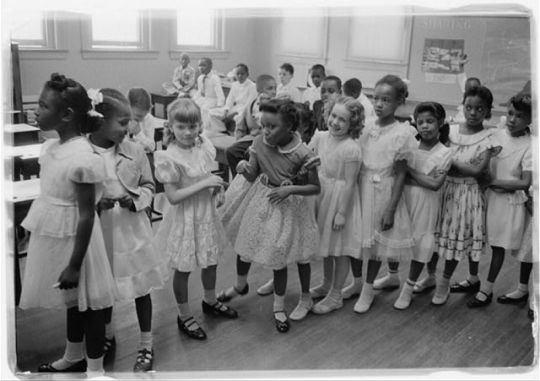

Photo:This image of an integrated classroom in the previously all white Barnard Elementary School in Washington, D.C., shows how the District’s Board of Education attempted to act quickly to carry out the Supreme Court decision to integrate schools in the area. Thomas J. O'Halloran. School integration, Barnard School, Washington, D.C., 1955, Library of Congress.

#Onthisday in 1954, the U.S Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that school segregation was declared unconstitutional. For more than a decade, Charles H. Houston, Dean of Howard University Law School, headed a team of lawyers that brought school desegregation cases in Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. After Houston’s death,Thurgood Marshall argued a joint appeal of these cases before the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education.

Part of their defense relied on the testimonies and research of social scientists during throughout their legal strategy. In the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark designed and conducted a series of experiments known as “the doll tests” to study the psychological effects of segregation on African American children. On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren issued a unanimous decision that racial segregation is unconstitutional, violating the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Learn more about the history of school segregation from the Library of Congress: bit.ly/2rqwcie