#elizabeth bishop

When I was a child, my mother gave me a remarkable book called The Diary of Helena Morley. The diary is real; it came from a young girl living in a remote mining town in Brazil in the 1890s. Helena is a sharp, studious girl who with a keen ear recounts the gossip of a town filled with hard-up prospectors like her father, dreaming of finding diamonds. We were living in Hawaii then, and as a lonely reader in a rural tropical landscape myself, I loved the antics of this much spunkier girl and liked to play pretend that I wasshe.

I didn’t realize it until much later, but the diary’s translator was the great American mid-century poet Elizabeth Bishop, who moved to Brazil in 1951 and lived there for many years with her lover.

When I was twenty, I first read Bishop’s poetry in a serious way, and it was like entering a room someone had decorated exactly to my liking–that Spartan wood chair just so, that picture slightly catawampus, flowers on the table and the sun entering through the window in the hours I most preferred.

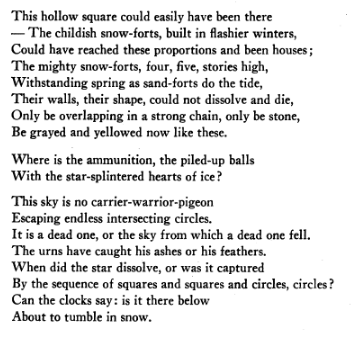

Bishop is said to have left blank spaces in her poems while she waited for the right word to come to her, and that kind of precision, her delicacy of diction, draws me to her work as to a found object, with profound respect and wonder. After all, she only published 101 poems during her lifetime.

I have changed since I first entered that room with those poems, and now, I find Bishop too precious, her rhymes too neat and prudish. But scratch a bit, and you understand the vivid depression underlying that propriety. Bishop’s father died in her infancy, her mother was committed to a mental institution when she was four, and her lover Lota killed herself. Bishop was an alcoholic, and once told Robert Lowell, “When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived.” I see in her poetry an attempt to bring care and order to the world without ever doing the violence of imposing upon it. “Love should be put into action!” she has a hermit scream in “Chemin de Fer.” Like Bishop, “an echo/ tried and tried to confirm it.”

What use does a journalist have for such a poet—a mediator of such soft and intimate worlds? There is so much ethical as well as aesthetic guidance in Bishop’s work, and I find myself thinking of her lines all the time as I work.

I think of her unwillingness to cede control of her subjectivity in the poem “In the Waiting Room,” and I’m reminded of the violence that portrayal and definition can do. A child reads the National Geographic and has a moment of rough disorientation in recognizing herself in the beings around her: “you are an I, you are an Elizabeth, you are one of them.” She asks, “Whyshould you be one too? I scarcely dared to look/to see what it was I was.”

When I travel, as I do a great deal, I think of the poem “Questions of Travel,” in which she asks, “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? Where should we be today? Is it right to be watching strangers in a play / in this strangest of theaters?” Yet she goes, and she watches, and she eyes tiny, light-touched details in those landscapes strange and familiar, like “rain so much like politicians’ speeches,” and “the weak calligraphy of songbirds’ cages.” These are the products of an ethics given in another poem as “watch it closely,” or, as she once told an interviewer, “I am very object-struck…I have great interest and respect…for what people call ordinary things.”

I will always think of knowledge as cold water, as Bishop says we imagine it to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

And I think of her use of old forms–the ballad, the sestina, simple metaphors–to tell stories of sadness and injustice. Find me a more moving, nuanced portrait of crime and inequality than “The Burglar of Babylon,” which opens with “a fearful stain:/ the poor who come to Rio, / And can’t go home again,” and chronicles a dramatic manhunt for the gangster Micuçú. When at last, a soldier “missed for the last time.” Bishop affords Micuçú the dignity of a complex character and implicates the whole city in the violent death.

That same empathy she extends even to Micuçú envelops the reader. In “The Shampoo,” Bishop ends on a gesture so loaded with humility and tenderness I will forever be grateful for it:

The shooting stars in your black hair

in bright formation

are flocking where,

so straight, so soon?

—Come, let me wash it in this big tin basin,

battered and shiny like the moon.

Cora Currier is a reporter with The Intercept who also writes about poetry and books. She has written for The New Inquiry, The Millions, Al Jazeera America, The Nation, and many other publications.

06.03.20 // dumb little girl/ you ought to be ashamed/ still dark. all alone/ yesterday I find almost impossible to lift/ just sleep

“She reports that she has begun to see each poem not as an “isolated event” but as part of “really all one long poem anyway” as “they go on into each other or over lap.””

In “One Long Poem”, Heather Treseler explores the intimate connection between poet and psychiatrist that is embodied in Elizabeth Bishop’s letters.

Post link

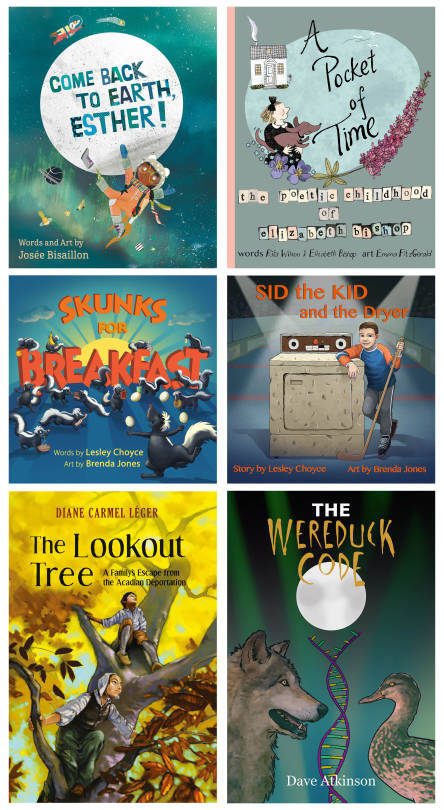

You know, we have some really exciting books coming down the pipes this season. This is just a taste. Check out these incredible covers!

Adult Titles (Fiction & Non-Fiction)

Children’s Titles (Picture Books + MG Fiction)

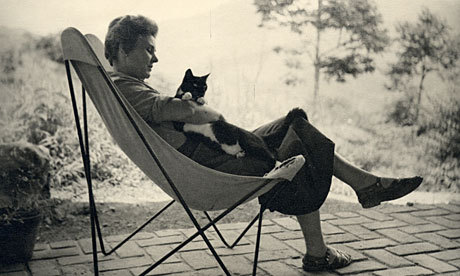

Happy belated birthday, Elizabeth Bishop.

Photograph by Louise Crane of Bishop and her cat, Minnow. Via the Cat Museum of San Francisco.

Post link