#women writers

You and your MC preparing for the final push:

I was more prepared for my divorce than most. Not only am I the only child of a single mother, but I have read Nora Ephron’s Heartburn every year since I was sixteen. This meant that by the time my marriage ended eleven years ago, I had read the novel eighteen times. It was almost prophetic; the story of a woman weathering an emotional storm and keeping her sense of humor has always resonated with me.

Throughout the book, Ephron’s fictional alter ego—Rachel Samstadt—provides a steady stream of trenchant observations like, “A child is a grenade. When you have a baby, you set off an explosion in your marriage, and when the dust settles, your marriage is different than what it was. Not better, necessarily; not worse, necessarily; but different.” Rachel’s humor and her spaghetti carbonara trump her ability to stay married. Heartburn is about a woman controlling the narrative of her divorce: if you’re going to be sad, you’d better be funny.

Ephron famously told Wellesley graduates in 1996 to be the heroines of their lives, and not the victims. I wonder what kind of movie she would have produced about a single mother in her forties dating online in contemporary New York City. She would have insisted on a happy ending, but there might have been some recognition of the stacked deck. Throughout my search for a really good boyfriend, my pursuit of poetry, full-time employment, and parenting my daughter, I have held onto Nora for hope. She married her third husband when she was 45. ‘WWND – What Would Nora Do,’ I asked myself. She wouldn’t feel sorry for herself. She’d get off her ass and write, and she’d get back in the dating saddle without a fuss. I haven’t always been true to these tenets, but at least I knew what I should be doing even when I wasn’t actually doing it.

I saw Ephron once with her husband. They were holding hands walking around an antiques show where I was working. It was a benefit for a botanic garden and I arranged for their photo to be taken in front of an array of flowers. I told her that Heartburn—the book not the movie—meant a lot to me. It was a moment she quickly forgot, no doubt, and I left feeling foolish. I didn’t need to ask Ephron for advice about my life, because I knew what she did. She defied the lemons of two failed marriages and turned them into When Harry Met Sally, the gold standard for all contemporary romantic comedies. She made Potatoes Anna, lima bean casserole, and lemonade.

For me, Ephron’s signature contribution to American culture is not her food or her films, but this short novel. Heartburn is based on her own life but I won’t call it autobiographical because, as Ephron pointed out, male novelists like Phillip Roth who also write from life don’t have their books labeled as such. With Heartburn, Ephron broke a necessary silence about divorce. It was a bestseller because its deceptively light touch makes any woman reading it feel like having a husband who has an affair and leaves is normal. Rachel is an everywoman. She is a mother, a worker, a cook and a friend. She lives up to Ephron’s credo: heroine, not victim, and she weaves recipes into her narrative. She wants you to bake your own key lime pie while cracking jokes, and to hold your head high.

The turning point in Heartburn is the salad dressing. After her husband’s betrayal, in an act of culinary and spiritual generosity, Rachel teaches him how to make her vinaigrette. Her ability to share the recipe is a sign. She can move on. This is just after the dinner party where she throws a pie in his face. She’s already sold her engagement ring to finance her escape and Ephron gives her book a happy ending–only it’s not another man, but Rachel’s return to her beloved Manhattan with her sons.

Often in the funniest of people there is real pathos. I remain haunted–and comforted–by these sentences that reveal that beneath the humor, decades after her divorce Ephron herself wasn’t entirely unscathed: “The most important thing about me, for quite a long chunk of my life, was that I was divorced. Even after I was no longer divorced but remarried, this was true. I have now been married to my third husband for more than twenty years. But when you’ve had children with someone you’re divorced from, divorce defines everything; it’s the lurking fact, a slice of anger in the pie of your brain.”

My daughter was with her father when I heard news of Ephron’s death three years ago. When we talked the next morning, I told her one of my favorite writers died. She said, “You mean the one who was seventy-one? We heard it in the car.” And I replied, “Yes. That one. She was important because she was a great feminist in an understated way. She wrote one of my favorite books and she led the way for women to write and direct successful movies. She loved her sons.”

What I didn’t say is that Ephron is now the guardian angel of divorced mothers and writers everywhere. She makes it possible for us to be both marked and reconciled, all the while believing not just in second acts, but the possibility of even more delicious thirds—served with pie, of course, strawberry ice cream on the side, and whipped cream, but only if it’s real and not out of a can.

Caledonia Kearns is the editor of two anthologies of writing by Irish American women, Cabbage and BonesandMotherland. Her essays have appeared in The Boston Globe, The Awl and The Hairpin, and her poems have appeared in Drunken Boat, Painted Bride Quarterly, and The Mom Egg Review, among others. She lives with her daughter in Brooklyn and has recently completed a Heartburn-inspired memoir-in-verse, Crossing the Gowanus.

When I was a child, my mother gave me a remarkable book called The Diary of Helena Morley. The diary is real; it came from a young girl living in a remote mining town in Brazil in the 1890s. Helena is a sharp, studious girl who with a keen ear recounts the gossip of a town filled with hard-up prospectors like her father, dreaming of finding diamonds. We were living in Hawaii then, and as a lonely reader in a rural tropical landscape myself, I loved the antics of this much spunkier girl and liked to play pretend that I wasshe.

I didn’t realize it until much later, but the diary’s translator was the great American mid-century poet Elizabeth Bishop, who moved to Brazil in 1951 and lived there for many years with her lover.

When I was twenty, I first read Bishop’s poetry in a serious way, and it was like entering a room someone had decorated exactly to my liking–that Spartan wood chair just so, that picture slightly catawampus, flowers on the table and the sun entering through the window in the hours I most preferred.

Bishop is said to have left blank spaces in her poems while she waited for the right word to come to her, and that kind of precision, her delicacy of diction, draws me to her work as to a found object, with profound respect and wonder. After all, she only published 101 poems during her lifetime.

I have changed since I first entered that room with those poems, and now, I find Bishop too precious, her rhymes too neat and prudish. But scratch a bit, and you understand the vivid depression underlying that propriety. Bishop’s father died in her infancy, her mother was committed to a mental institution when she was four, and her lover Lota killed herself. Bishop was an alcoholic, and once told Robert Lowell, “When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived.” I see in her poetry an attempt to bring care and order to the world without ever doing the violence of imposing upon it. “Love should be put into action!” she has a hermit scream in “Chemin de Fer.” Like Bishop, “an echo/ tried and tried to confirm it.”

What use does a journalist have for such a poet—a mediator of such soft and intimate worlds? There is so much ethical as well as aesthetic guidance in Bishop’s work, and I find myself thinking of her lines all the time as I work.

I think of her unwillingness to cede control of her subjectivity in the poem “In the Waiting Room,” and I’m reminded of the violence that portrayal and definition can do. A child reads the National Geographic and has a moment of rough disorientation in recognizing herself in the beings around her: “you are an I, you are an Elizabeth, you are one of them.” She asks, “Whyshould you be one too? I scarcely dared to look/to see what it was I was.”

When I travel, as I do a great deal, I think of the poem “Questions of Travel,” in which she asks, “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? Where should we be today? Is it right to be watching strangers in a play / in this strangest of theaters?” Yet she goes, and she watches, and she eyes tiny, light-touched details in those landscapes strange and familiar, like “rain so much like politicians’ speeches,” and “the weak calligraphy of songbirds’ cages.” These are the products of an ethics given in another poem as “watch it closely,” or, as she once told an interviewer, “I am very object-struck…I have great interest and respect…for what people call ordinary things.”

I will always think of knowledge as cold water, as Bishop says we imagine it to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

And I think of her use of old forms–the ballad, the sestina, simple metaphors–to tell stories of sadness and injustice. Find me a more moving, nuanced portrait of crime and inequality than “The Burglar of Babylon,” which opens with “a fearful stain:/ the poor who come to Rio, / And can’t go home again,” and chronicles a dramatic manhunt for the gangster Micuçú. When at last, a soldier “missed for the last time.” Bishop affords Micuçú the dignity of a complex character and implicates the whole city in the violent death.

That same empathy she extends even to Micuçú envelops the reader. In “The Shampoo,” Bishop ends on a gesture so loaded with humility and tenderness I will forever be grateful for it:

The shooting stars in your black hair

in bright formation

are flocking where,

so straight, so soon?

—Come, let me wash it in this big tin basin,

battered and shiny like the moon.

Cora Currier is a reporter with The Intercept who also writes about poetry and books. She has written for The New Inquiry, The Millions, Al Jazeera America, The Nation, and many other publications.

Essay by Kristine Esser Slentz

“They needed to hear more about being with a woman. Thank you for sharing that,” my friend, and the only other woman at the table, whispered to me.

•

“What is the best and worst sexual experience you’ve had?” was the question prompted by a viral New York Timesarticle stating the 36 questions that can supposedly lead to love in relationships. All of us New York City transplants were out at a bar when this conversation enveloped us: four straight-identifying men, one woman – we’ll call her K – who was currently exploring her sexual identity and married to one of the men, and me—the unabashed bisexual.

They wanted to go around in a circle, of course starting with me—the furthest acquaintance from this particular friend group. I smiled, dropped my head to my dark beer, and passed while I “thought about it.” They graciously accepted while I started to internally ponder my own landmine of sexual experiences…

The men at the table added their escapades to this seemingly bar-banter of a conversation. Each one sharing their worst experiences with women, which consisted of: women’s untimely period problems, women’s bodies becoming too sensitive after orgasm; and women accidentally urinating while drunk, while the best moments mostly boasted tender minutes in a lover’s embrace and exciting locations in the backseat of a car.

This led to some pause, and not just from me. There were follow-up questions: Was this the first time you experienced a sexual encounter during someone’s cycle? Could you not touch her at all after orgasm? So, then what did you do? So, like, how much pee was there? Did she care? How did she feel about it? And overall, do you still talk to her?

In that moment, the thoughts that I ashamedly felt I couldn’t say aloud were: Is this fucking serious? Is this the conversation we’re having about sex as thirty-somethings in the “best city in the world” right now?Stressing over normal bodily functions and disgracing the women for having them as if they are unusual and depraved?

•

My mind kept flipping through sexual scenarios I’ve been in, but mostly the horrific ones: multiple rapes, countless harassments, and wondering which of the following scenarios was worse: that time I thought I was sneaking out with a friend for some car sex but found that he’d planned for his large friend to be there as well, which ended with a drive into woods I didn’t recognize? Or the time I was drugged and woke up naked next to a stranger? Certainly, these would not do because our social mores dictate that these things remain unmentioned to avoid discomforting or upsetting people. This was at a bar during a festive moment — a very public space — where a woman killing the vibe could be the biggest rule to break of all. Instead, I decided to pivot into a mad mental dash to bar-appropriate erotic hijinks. What would be amusing? What would be funny? What would keep the conversation light and the party going?

•

Then, it was K’s, the only other present woman, turn to speak. Her best experience included a time with her husband in a sensual backseat rendezvous, which also happened to be his best experience too. Her worst experience was with a past partner. He had asked her for sex and she had not wanted to. He kept pushing to make love — he did not want to take no for an answer. Finally, she gave in. After he was finished, he said to her, “You know you wanted it.” At this, she looked down at her beer nodding. Then tells the table that that was the last time she ever had sex when she didn’t want to. “It was fucked up,” K said.

•

Now, I had to speak. For my worst, I decided to go with the time my now-husband fell asleep on me while we were having sex. At this, one of my male friends asked for clarification, “But was he tired or drunk?” Why, yes — he had worked, acted in a show, and had a couple of beers. He gave a nod of approval. Interesting, I thought, or was it really? This way of questioning to defend another man is something I didn’t really notice before, and why? I pocketed that note and moved on with my turn. For my best, I depicted the first time I was “with” a woman in the very back of an SUV full of folks. Or better described as: the moment I knew I was truly attracted to women.

Stepping back into beer three that had now been switched to a cheap domestic, it wasn’t lost on me that these lovely, well-intentioned men tended to blame their partner for their worst experience, while I, the woman, subconsciously took on the responsibility of being the “worst.” Why did both K and I have such shielding body language? That reaction of being faced with these traumatic events had us looking away from the men and down into our supposedly liquid courage. This wasn’t the first time I’d detected something like this or the first conversation that had brought up not only the discrepancy between what a “best” and “worst” experience is, but also who gets the responsibility of being the worst in said experience. Once again, I was struck by how commonplace it is for women to have abusive or simply unsatisfactory stories in regards to sex. K and I both had them even though she was much braver in sharing hers than I was. I was also witness to further evidence that men seemingly have no clue that women — their friends and lovers — have many horrific stories as their go-to “worst.” They themselves have never experienced a “worst,” nor do they get that it is feasible that they may have been someone’s worst — even if it wasn’t blatantly abusive.

•

Then, K turned to me and said, “Thank you.” I was shocked. Shocked that she thanked me. Shocked that the men felt blameless. Shocked that the women felt shameful. Sadly, I was shocked that a woman would thank me for telling my truth.

Kristine Esser Slentz is a queer, experimental poet from northwest Indiana and the Chicagoland area. She is a Purdue University alum who double-majored in English literature and creative writing. Recently, she earned her MFA in creative writing (poetry) at City College of New York where she is an adjunct professor and an organizer of the MFA Reading Series. KRISTINE’s full-length manuscript has been long-listed, is a 2020-21 Glass Poetry Chapbook Series finalist, F®iction Spring 2020 Flash Fiction contest finalist, and will be completing a residency with Poets Afloat in the near future. Some places her poetry has appeared in or is forthcoming include Yes Poetry, Moonchild Magazine, The Shallow Ends, Glass Poetry, Pink Plastic House, Barren Magazine, Crab Fat Magazine, Philosophical Idiot, and Flying Island Journal where she was nominated for a 2017 Pushcart Prize.

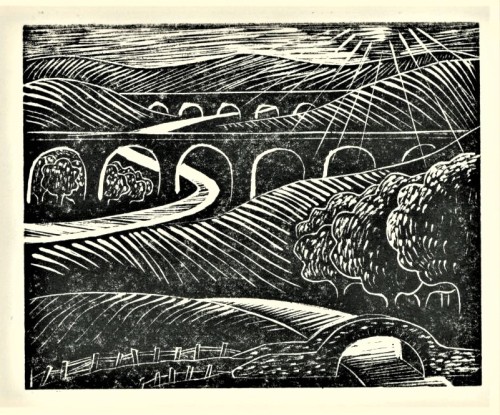

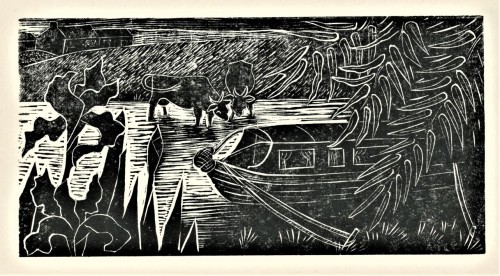

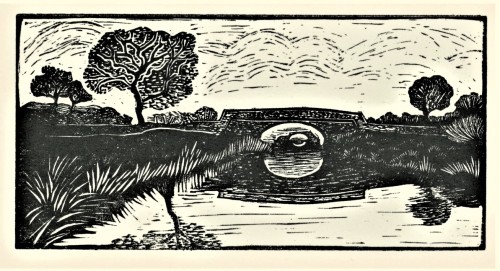

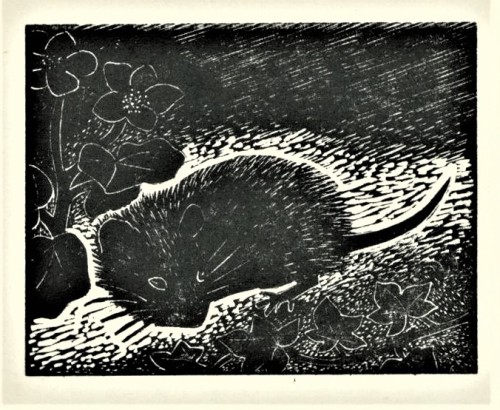

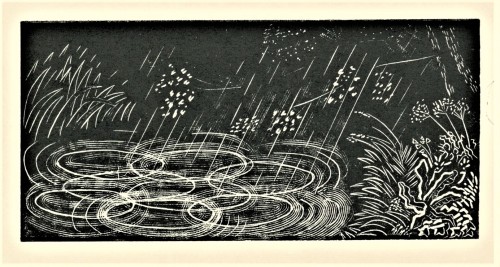

Wood Engraving Wednesday

LINDA LEATHERBARROW

This week we present a few small wood engravings by the Scottish-born author and illustrator Linda Leatherbarrow from her chapbook A Floating Diary: A Collection of Words and Wood Engravings Following a Week Afloat on a Narrow Boat, handprinted in London by Leatherbarrow in an edition of 100 copies at her own Little Bird Press in 1980.

An award-wining short story writer, Leatherbarrow also trained as an artist at Hornsey College of ArtandWalthamstow School of Art, and in the late 1970s started Little Bird Press for her own writing and that of her friends, illustrated with original prints in wood engraving, linocuts, and silk screen. “I began,” she writes, “with an Adana hand press on a table in a corner of my bedroom then progressed to my own workshop above a car showroom on Tottenham High Street,” and would well her books “at Covent Garden Market, craft fairs and bookshops throughout the UK.” She continued illustrating and handprinting until the mid-1980s, when she began writing short stories to great success.

Leatherbarrow has also worked as a librarian, a literary festival organizer, and a university lecturer. In 2010, she retired from lecturing, but continues to write from her home in southwest Scotland.

View more posts with women wood engravers.

Viewmore posts with wood engravings!

Post link

Flannery O’Connor is getting her own postage stamp!

Born in Georgia, O’Connor attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and was always determined to be an author. She had lupus, so at age 25, she moved back to Georgia, where her mother helped take care of her. O'Connor used crutches to get around, raised peacocks, and wrote novels like Wise Blood that came to define Southern Gothic. Her work was twice nominated for the National Book Award before she died in 1964 at just 39 years old.

Post link

Book Review- On Being Human by Jennifer Pastiloff

[image description: a photo of the book On Being Human: A Memoir of Waking up, Living Real, And Listening Hard

Okay buckle up babes.If you’ve been here a while you’ll remember Beloved Jen from this post. AND after months let’s get it going with my review.

At first blush, On Being Human* and really Jen’s stuff probably doesn’t seem like my shit. Like I hate doing yoga and on the surface at first…

Pandit Nehru and Hyderabad Sansthan

New from Tim Duggan Books, Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars, by Francesca Wade.

Post link

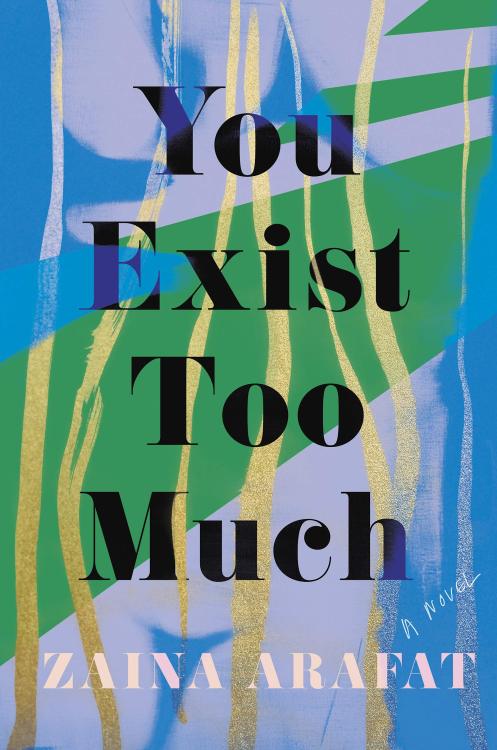

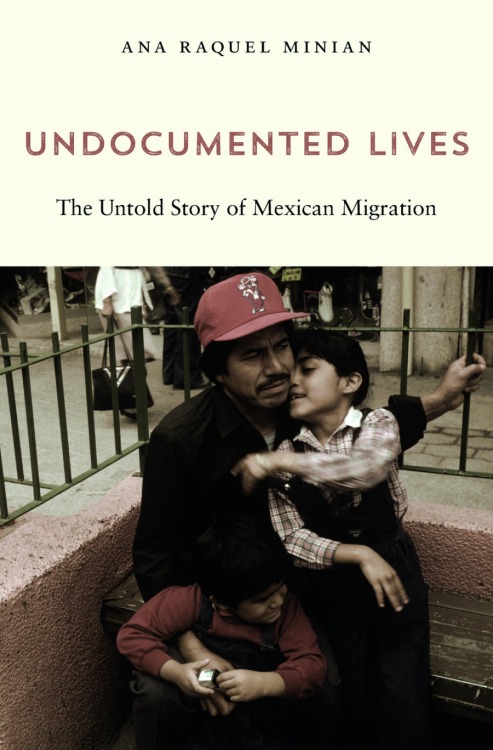

Now in paperback from Harvard University Press and Stanford Associate Professor Ana Raquel Minian, Undocumented Lives: the Untold Story of Mexican Migration.

Post link

New from Yale University Press, I Live In the Slums, by Can Xue, translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping. In Can Xue’s world the superficial is peeled away to reveal layers of depth and meaning. Her stories observe no conventions of plot or characterization and limn a chaotic, poetic state ordered by the extreme logic of philosophy.

Post link

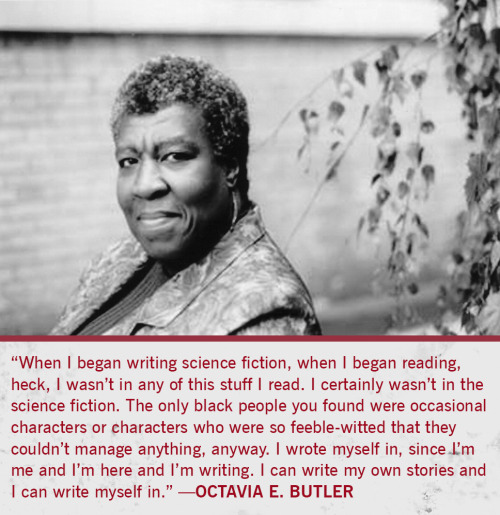

Octavia Estelle Butler (1947–2006), often referred to as the “grand dame of science fiction,” was one of the few Black women writers in that genre. She was the author of many novels including Dawn, Wild Seed, Parable of the Sower, and Kindred. Her writing is known for blending social issues with fantastic settings. Her many honors include two Hugo awards (Bloodchild and “Speech Sounds”) and two Nebula Awards (Bloodchild and Parable of the Talents). In 1995 she was awarded a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Grant. Butler continues to receive posthumous recognition for her writing: in 2010, she was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. And in 2012, she was honored with a Solstice Award from the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America. To read more, visitwww.octaviabutler.org.

Post link

How to Walk Away &Things You Save in a Fire

by Katherine Center

I have long believed that you have to be in the mood to read a certain type of book. Like with any relationship, the timing must be right, otherwise, you won’t be open to the writing voice/style/ content. Hot tea doesn’t quench every thirst and sushi doesn’t sate every palate. It’s possible Katherine Center’s books are the exception to that rule.

In content, the ironically and aptly titled How to Walk AwayandThings to Save in a Fire, are vastly different. How to Walk Away follows a lovelorn protagonist as she suffers quite immediately from a tragic accident throughout her complicated recovery; Things to Save in a Fire follows a stoic firefighter as she navigates a new bro-filled New England landscape.

In style, Center manages to create reading experiences that are simple without being simplistic and heart-warming without being heart-cloying. In short, they are satisfying reads - well crafted with personal triumph at the center, padded with bits of romance, conflict and existential crisis. The books are well-written, practically paced, bittersweet and fluid and with enough complication to keep the pages turning. And what’s particularly gratifying about these books is that the happy endings are not necessarily what you’d expect.

Things You Save in a Fire will be released August 2019, but you can grab a copy of How to Walk Away now. In fact, I just saw it on sale in Barnes & Noble.

It’s refreshing to know that there are books out there that are enjoyable no matter what the season. Like iced tea - a little sweet, a little tart, but extremely satisfying whenever you are thirsty for something tasty.

*B3 would like to thank St. Martin’s Press for the ARCs!

Post link

ALL THE BIRDS IN THE SKY by Charlie Jane Anders

I bought All the Bird in the Sky for a friend. Her bookclub vetoed this as a book suggestion, but she was excited about it, so in an act of solidarity with her deeply-rooted belief that books should be worthy of discussion, I deposited it on her bed one day and blamed book fairies for the drop.

Then I promptly started reading it myself and stole it across the country with me before she could open it. (I had the best intentions. Also, spending money on a book purchased for a friend does not count as buying a book for yourself.)

A unique combination of the post-apocalyptic world of Vanessa Vaselka’s ZAZEN and the gritty magical reality of Lev Grossman’s The Magicians, Anders’ novel is possibly the only book that would be accurately categorized as Sci-Fi/ Fantasy.

(There is this odd phenomenon - a bizarre combination of sci-fi and fantasy genres - that proliferates search engines and bookstores alike. It’d be like grouping cats and dogs together in a shelter section called Dats and considering the choice between the two arbitrary - which any cat or dog parent will indubitably dispute. But, this book is truly both Sci-Fi and Fantasy.)

In the rich world Anders has invented, thick with angst and dense with meaning, a 2-second time travel device and talking animals coexist. It’s nostalgic and dread-filled, a children’s book for adults, an embedded warning for our collective future.

Turning each page sounds the death nell for the end of the world - or a solemn harbinger for science that contains real magic - or is it magic that contains real science? - that will save us all.

Post link

I have heard all of the stories about girls like me, and I am unafraid to make more of them

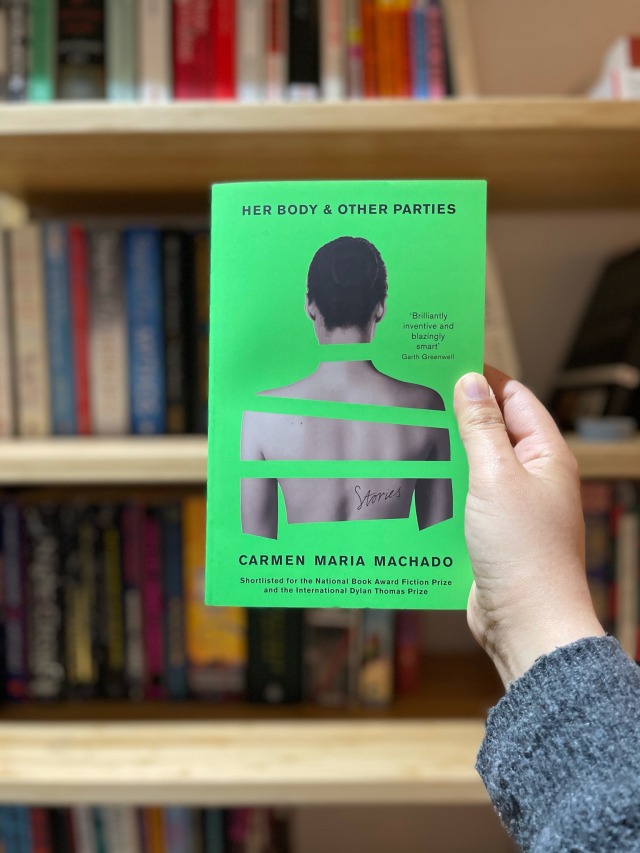

Currently reading; Her Body and Other Parties, a collection of short stories by Carmen Maria Machado.

I am three stories in, and so far I am loving it. There is something so enchanting about the way Machado writes these stories…they almost wrap around you as you read them, and nothing else matters during that time…

At this stage, I would highly recommend this book

Well, telling the secret would ruin the sunrise

Don’t want to ruin the fun!

What if we lose our magic?

What if we lose our innocence?

Telling would mean that we would have to deal with the world

That would love to burn us at the stake!

Saying we’re martyrs for an agenda we chose

But I didn’t chose to love you…

Pretty bold of you to say that I’m overreacting

Would only acknowledge my bleeding

Accompanied by blood curdling screaming!

Because it began to stain your clothes

Left me to rot…

While you bought a new shirt.

Said it was a pity I died!

But, I’ve survived worse.

When You Learn Your Mother Was a Serious Writer Only After She’s Gone

In March 2021, my mother, Nancy Bourne, a lifelong nonsmoker, died of lung cancer. Two weeks before that, though, as she cycled in and out of hospital wards, she was on her laptop sending off a flurry of query letters to literary agents asking for their help in selling her first novel. Six months before that she learned that another book of hers, a collection of short stories titled Spotswood, Virginia, would be published by a university press. In fact, in the last decade of her life she wrote dozens of short stories and published 35 of them.

But perhaps what’s most remarkable about my mother’s late-life literary renaissance is how few people knew about it. It wasn’t a secret, exactly. She belonged to two writing groups and took numerous creative writing classes and workshops. But outside a tight circle of family members and writing friends, she rarely talked about it.

READ MORE

Our September preview showcases stories of familial dysfunction from the brilliant Natalia Ginzburg and Susan Taubes. The beloved Italian author considers the strained relationships between parents, children, and siblings, while Taubes’s Divorcing, out of print for over fifty years, takes up the collapse of a marriage and a sense of self.

Susan Taubes, Divorcing

Sophie Blind is divorced—and not merely from her husband but from herself, as her own memories and emotions seem increasingly remote. In luminous fragments, the narrative flits from New York to her childhood home of Budapest, considering her parents’ divorce alongside her own. Fans of Renata Adler and Elizabeth Hardwick, take note: this dreamlike novel from 1969 is a forgotten precursor to their lyrical work in the ’70s. Taubes, a close friend of Susan Sontag, committed suicide at forty-one soon after its publication.

Natalia Ginzburg, Valentino and Sagittarius

From the celebrated author of Family Lexicon comes these two novellas of dysfunctional family life. In Valentino, a sister tells the story of her doted-upon brother, who upends his family’s expectations when he suddenly marries an ugly but wealthy older woman and begins a secret affair with her male cousin. In Sagittarius, a daughter and her hypercritical mother move to the suburbs, where she becomes obsessed with impossible dreams of opening an art gallery.

Denise Miotke is a mom, a real estate agent, a reader for the Austin Film Festival, one of my oldest friends - and a screenwriter. I loved talking with her about her writing journey - she’s wise and funny and you’re going to love her.

In this episode we talk found family; fence disputes; Bronte inspiration; how poetry and screenwriting are linked; how bad screenplays are all similar; authenticity; and so much more.

Anywhere you get podcasts or https://bit.ly/LWYLep56

Cizí akvária/Other people’s aquariums

Na cizích bytech mám ráda, že uspořádání věcí

v prostoru je dané, mohu je pouze obhlížet,

jak dlí.

V mém bytě mě znervózňuje opak

– nedefinitivnost.

Jako v životě. Křehkost, zranitelnost dnešního stavu.

To, že bych teoreticky každou chvíli mohla vším

pohnout jinam. Mé věci, šaty, skříně a stoly jsou prosyceny provizorností mého pobývání na zemi, mou nejistotou a smrtelností.

Všechna cizí akvária nekriticky přijímám (pokud v nich není umělohmotný hrádek), jen s tím svým se nedokážu smířit, zdá se mi tmavé, jeho špína padá na mou hlavu,

jsem svědkem ryb, které v něm umírají a které musím vyhazovat do záchoda,

květiny v něm musí být přeskupovány, nahrazovány novými, protože žloutnou.

Ale už mnoho let ho držím při životě, kupuji nové ryby, topím jim, čistím písek a kameny a nedokážu s tím přestat. Ovšem, že dokud nepraskne a nevyteče, svoje akvárium dobrovolně nikdy nezruším.

-

What I like about other people’s apartments is that the way

objects are arranged in space is given, I can only

watch them be.

In my own apartment what makes me nervous is the opposite —

nothing is definitive.

As in life. Fragile, vulnerable the way things are today.

I could, theoretically, move anything

at any time. My things, clothes, wardrobes and tables

are suffused with the provisional nature of my existence

here on earth, with my uncertainty, my mortality.

I uncritically accept all aquariums belonging to other people

(as long as there is no plastic castle inside) only my own aquarium I cannot come to terms with, it appears dark, its dirt falls on my head

I witness dying fish that I then have to throw into the toilet

the flowers in it have to be endlessly moved around replaced with new ones because they turn yellow.

Yet, I keep it alive for years, buy new fish, keep them warm, clean the sand and stones unable to stop. Of course, until it cracks and the water pours out I will never voluntarily abolish my aquarium.

Kateřina Rudčenková

Translated from Czech byAlexandra Büchler

The author reading her poem at the Václav Havel Library in Prague