#french art

Claus de Werve (Netherlandish, 1380-1439)

Mourner from the Tomb of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

1404-1410

Alabaster

“Throughout most of their history these alabaster mourners have evoked a sense of awe and mystery as well as curiosity and admiration. They were originally arranged in processional order around the sides of the ducal tomb within a marble arcade in the Chartreuse de Champmol. The realistically carved mourners remain the most famous elements from Philip the Bold’s tomb. Carved by Claus de Werve, no two are alike. They retain minute details of costume and features, and the faces of some are nearly portrait-like in their depiction of facial creases and expression, suggesting actual individuals, while the faces of others are partly obscured by their cowls.”

One of three mourners currently in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Image and description from the Cleveland Museum of Art’s online collection pages (1,2, and 3 (shown here)).

Post link

Claus de Werve (Netherlandish, 1380-1439)

Mourner from the Tomb of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

1404-1410

Alabaster

“Throughout most of their history these alabaster mourners have evoked a sense of awe and mystery as well as curiosity and admiration. They were originally arranged in processional order around the sides of the ducal tomb within a marble arcade in the Chartreuse de Champmol. The realistically carved mourners remain the most famous elements from Philip the Bold’s tomb. Carved by Claus de Werve, no two are alike. They retain minute details of costume and features, and the faces of some are nearly portrait-like in their depiction of facial creases and expression, suggesting actual individuals, while the faces of others are partly obscured by their cowls.”

One of three mourners currently in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Image and description from the Cleveland Museum of Art’s online collection pages (1,2 (shown here), and 3).

Post link

Claus de Werve (Netherlandish, 1380-1439)

Mourner from the Tomb of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

1404-1410

Alabaster

“Throughout most of their history these alabaster mourners have evoked a sense of awe and mystery as well as curiosity and admiration. They were originally arranged in processional order around the sides of the ducal tomb within a marble arcade in the Chartreuse de Champmol. The realistically carved mourners remain the most famous elements from Philip the Bold’s tomb. Carved by Claus de Werve, no two are alike. They retain minute details of costume and features, and the faces of some are nearly portrait-like in their depiction of facial creases and expression, suggesting actual individuals, while the faces of others are partly obscured by their cowls.”

One of three mourners currently in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Image and description from the Cleveland Museum of Art’s online collection pages (1 (shown here),2, and 3).

Post link

Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean

Made in Burgundy, France

circa 1250

Limestone

‘According to tradition, the monastery of Moutiers-Saint-Jean was founded by the first Christian kings of France, Clovis I and his son Clothar I. They are almost certainly depicted in the standing figures presenting their charters, now installed in the embrasures on either side of the portal. The small seated figures in the flanking niches represent biblical personages believed to prefigure or foretell Christ’s Crucifixion. The tympanum above the doorway depicts Christ crowning the Virgin as the Queen of Heaven. This portal, probably from the north aisle of the cloister, would have led from the monastic precinct into the abbey church. The portal suffered severe damage during the sixteenth-century Wars of Religion; the heads of the two kings may have been repaired in the seventeenth century.’

The doorway is in the collection of The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Description and image taken from the Met’s website, where you can zoom in on photos of the doorway.

(**Tour 5/5)

Post link

Cloister from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert

French

Late 12th c.

Limestone

‘Situated in a valley near Montpellier in southern France, the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert was founded in 804 by Guilhem (Guillaume) au Court-Nez, duke of Aquitaine and a member of Charlemagne’s court. By the twelfth century, the abbey had been named in honor of its founder and had become an important site on one of the pilgrimage roads that ran through France to the holy shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. With the steady visits of travelers en route to the shrine and the gifts they brought with them, a period of prosperity came to the monastery. By 1206 a new, two-story cloister had been built at Saint-Guilhem, incorporating the columns and pilasters from the upper gallery seen here. Most of these columns are medieval versions of the classical Corinthian column, based on the spiny leaf of the acanthus. This floral ornamentation is treated in a variety of ways. Naturalistic acanthus, with clustered blossoms and precise detailing, is juxtaposed with decoration in low, flat relief, swirling vine forms, and even the conventionalized bark of palm trees. Among the most beautiful capitals are those embellished by drill holes, sometimes in an intricate honeycomb pattern. Like the adaptation of the acanthus-leaf decoration, this prolific use of the drill must have been inspired by the remains of Roman sculpture readily available in southern France at the time. The drilled dark areas contrast with the cream-colored limestone and give the foliage a crisp lacy look that is elegant and sophisticated.

Like other French monasteries, Saint-Guilhem suffered greatly in the religious wars following the Reformation and during the French Revolution, when it was sold to a stonemason. The damages were so severe that there is now no way of determining the original dimensions of the cloister or the number and sequence of its columns. Those collected here served in the nineteenth century as grape-arbor supports and ornaments in the garden of a justice of the peace in nearby Aniane. They were purchased by the American sculptor George Grey Barnard before the First World War and brought to this country. A portion of the original cloister remains at Saint-Guilhem.’

The cloister is in the collection of The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Description and image taken from the Met’s website. You can see more photos of the cloister here on their site.

(**Tour 4/5)

Post link

Narbonne Arch

French

circa 1150-75

Marble

‘This semicircular arch comprises seven stone blocks (known as voussoirs) decorated with eight real and fantastic animals: left to right, a manticore (“man-eater” in Persian, with the face of a man, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion); a pelican (symbol of Christ); a basilisk (dragon with a serpent’s tail, signifying the power to kill); a harpy (half- woman, half-bird creature whose sweet song lures men to their deaths); a griffin (with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle); an amphisbaena (serpent with a head at either end); a centaur (with the head and torso of a man and lower body of a horse); and a crowned lion. These are all animals familiar from medieval bestiaries: texts compiled in the twelfth century describing such creatures and explaining their moral and religious associations.

The closest parallel to the carving style of the arch can be found in the nave capitals of the mid-twelfth-century church of Saint-Paul-Serge in Narbonne, but the original location of the arch remains unknown.’

The arch is in the collection of The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image and description taken from the Met’s website.

(**Tour 2/5, see this post for more information)

Post link

View in the Île-de-France

Jean-Victor Bertin (French; 1767–1842)

ca. 1810–13

Oil on canvas

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

Post link

Towards Cascata Vecchia, Tivoli

Jean-Victor Bertin (French; 1767–1842)

1806

Oil on canvas

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Post link

Villas at Trouville

Gustave Caillebotte (French; 1848–1894)

1884

Oil on canvas

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

Post link

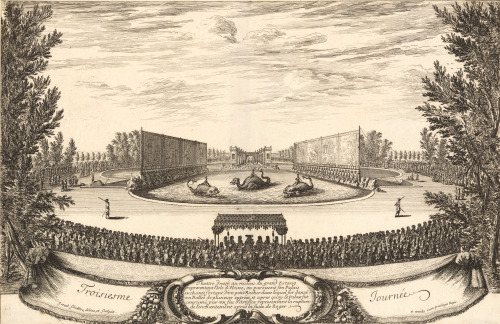

Le palais d'Alcine = The Palace of Alcina

Israël Silvestre (French; 1621–1691)

ca. 1673–79

Etching

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division

Caption: Troisiesme Journée

Caption subtitle: Theatre dressé au milieu du grand Estang representant l'Isle d'Alcine, ou paroissoit son Palais enchanté sortant d'un petit Rocher dans lequel fut dancé un Ballet de plusieurs entrées, et apres quoy ce Palais fut consumé par un feu d'artifice representant la rupture de l'enchantement apres la fuite de Roger.

Scene from a ballet presented at Versailles in May 1664. On a pond before her palace, the enchantress Alcina rides on a sea-monster, flanked by two nymphs on dolphins.

Les plaisirs de l'isle enchantée was a seven-day series of entertainments held at Versailles, beginning on May 7, 1664. Given in honor of the queen mother, Anne of Austria, and Queen Marie Thérèse, it provided a pretext to display the power and wealth of the court of Louis XIV. This print depicts a scene from the ballet Le palais d'Alcine, arranged by the Duc de Saint-Aignan to music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, with scenic design by Carlo Vigarani. Presented on the third day of entertainments, the ballet was based on a subplot from Ariosto’s epic poem Orlando furioso, in which Ruggiero (Roger of the print’s caption) attempts to escape the toils of the enchantress Alcina. As the caption reveals, the ballet closes with the destruction of Alcina’s palace amid a display of fireworks.

Probably a plate from Les plaisirs de l'isle enchantée, ou, Les festes et divertissements du Roy à Versailles (Paris: L'Imprimerie royale, 1673–79).

Post link

Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Menu de l'Amour; pommes de terre frites, 1884

[Source: LotSearch]

Post link

Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Woman with Putti at Spring, 1875

[Source: Bukowskis]

Post link

![Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Reflection, n/d[Source: LotSearch] Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Reflection, n/d[Source: LotSearch]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/aa50db75e210433c49f9c6421081bc34/7ace4279d7b9f92d-f7/s500x750/b71af86c5ceb827b80406673e01ebcd8b9e06e00.jpg)

![Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Woman with Putti at Spring, 1875 [Source: Bukowskis] Jean-Ernest Aubert (1824-1906, French) ~ Woman with Putti at Spring, 1875 [Source: Bukowskis]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/9f515fdf027573293b66508447ddd9fe/0483dca159c2658a-fe/s500x750/c80413a387fb4b63a2bf589f19b0df1db3d6127f.jpg)