#french impressionism

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/15/16)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919)

Two Sisters (On the Terrace)(1881)

Oil on canvas, 100.5 x 81 cm.

The Art Institute of Chicago (Mr. & Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection)

“Oh what a joy to indulge in the exquisite ecstacy of painting…to me, a painting must be an agreeable, joyful, pretty thing – yes, pretty, really. Why shouldn’t art be pretty? There are enough unpleasant things in the world.” – Pierre-Auguste Renoir

There’s justice in Renoir’s reply to his critics, but his art not merely “pretty,” however much it gravitated towards the comely and pleasant and eschewed the ugly and disturbing. From all accounts possessed of a singularly cheerful temperament, Renoir imbued his scenes with a “joie de vivre” rare in the art of any era. His paintings radiate human warmth, affording their subjects all possible understanding, tolerance, and respect that his son Jean, the great filmmaker, was to do in another medium.

Renoir concluded his fifteen-year exploration of the theme of bourgeois leisure with this superb painting of 1881. The setting is a terrace of the Restaurant Fournaise, an establishment in the village of Chatou, on the Seine, where Renoir had previously executed “The Rowers’ Lunch,” among other works.

A celebration of the beauty of spring and the promise of youth, “Two Sisters (On the Terrace)” is a technical and compositional tour de force, a virtuoso display of vibrant color and variegated brushwork. The almost life-sized figures (who were not sisters, as indicated by the work’s original title, but unrelated models) occupy a shallow space in front of a terrace railing; behind them quivers a lively, leafy landscape that brings their sharply delineated forms into vivid focus. The two girls’ faces are extraordinarily refined —- revealing Renoir’s new emphasis on draftsmanship —- and their porcelain complexions are uncompromised by reflections or shadows. The young child’s irises are an almost startlingly clear, translucent blue, suggestive of the artist’s desire to help us see the world afresh, through innocent eyes.

As always Renoir transformed what he saw, infusing nature with the artifice necessary to create harmony. For example the foliage behind the figures cannot rival the artificial flowers that adorn the little girl’s hat. The balls of yarn in the basket, somewhat out of context in this outdoor setting, also refer to the artist’s palette and his skill in deploying it. Shown in 1882 at the seventh Impressionist exhibition, “Two Sisters” signaled Renoir’s impending departure from Impressionism’s preoccupation with rendering transient effects of light by means of flickering brushwork, while summarizing his dedication to the subjects and themes he had presented so buoyantly.

(adapted from several sources)

Renoir’s work is the subject of this MWW exhibit/gallery:

* Renoir & The Joy of Painting

Post link

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/8/16)

Vincent Van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890)

Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree [after Hiroshige] (July-Sept. 1887)

Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

At the Paris World Fair of 1867 Japanese culture burst upon the European scene with the force of a megaton bomb. Kimonos and bamboo screens became all the rage; Parisian ladies turned the tea ceremony into a competitive sport; Japanese woodblock prints appeared in every corner shop and were greedily snatched up by a public infected with “la fièvre japonaise.”

A few decades later, when the fever had subsided and the novelty had wore thin, an influential French critic, looking back over the phenomenon, declared that Japan had invigorated modern art in the same way that classical antiquity had the Renaissance. And the artist upon whom it had the most profound effect was Vincent van Gogh. As early as 1885 in Antwerp he started a collection of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which by 1887 numbered in the hundreds. His enthusiasm went well beyond collecting: in spring 1887 he organized an exhibition of Japanese prints at the Cafe Tambourin, and that summer copied three prints, two by Hiroshige, in his personal collection. (Copying other works was the artistically unschooled Van Gogh’s method of learning.) Suddenly, the muted color palette of his Paris period brightened, previously shunned black-white contrasts appeared, the daring diagonals and jolting shifts in perspective of the prints found their way into his repertoire. Only one thing remained for Van Gogh, who never did anything in half-measures: he must “find his own Japan.” So he went to Arles, and the rest is, as they say, history.

This painting is a copy of a print in Hiroshige’s last collection, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.”

The MWW already contains a substantial number of works by Van Gogh in five separate exhibits, which include ALL his extant paintings, as well a selection of his drawings from each period. Extracts from Van Gogh’s literate and very revealing letters to his brother Theo accompany the pictures, along with the usual background information gleaned from many sources.

* Van Gogh in Holland (Oct. 1881-Feb. 1886)

* Van Gogh in Paris (March 1886-Jan. 1888)

* Van Gogh at Arles (Feb. 1888-April 1889)

* Van Gogh at St.-Rémy (May 1889-May 1890)

* Journey’s End: Van Gogh at Auvers (20 May-29 July 1890)

Post link

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/1/16)

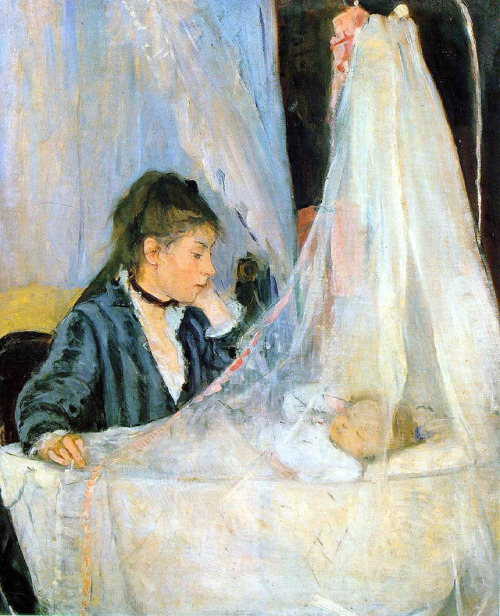

Georges-Pierre Seurat (French, 1859-1891)

Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86)

Oil on canvas, 207.6 x 308 cm.

The Art Institute of Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection)

With this picture Georges Seurat recast Impressionism, using as his guides both optical theory and idealist aesthetics. When first shown in 1886, at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition, this impressive painting of middle-class Parisians relaxing on an island in the Seine just west of the city attracted considerable attention, and no wonder. Although many artists had portrayed similar subjects in recent years, none had used so rigorous and schematic a style. The hieratic figures, shown mostly in profile or straight-on, recall ancient Egyptian reliefs, and the deliberate compositional rhythms amount to a pointed critique of Impressionist ephemerality. As if to dispel any lingering doubts on this point, Seurat also rejected free, sketchy handling, choosing instead to render the entire scene with meticulous, dotlike touches of paint, which, viewed from a certain distance, resemble nothing so much as tapestry stitching.

Seurat conceived these little “dots” and dashes to exploit scientific theories of optical mixture, according to which discrete applications of certain colors, if immediately juxtaposed, will blend in perception to form new ones. The result was meant to be brilliantly luminous; one critic described a “vibration of light, a richness of color, [and] a sweet and poetic harmony.” Seurat arrived at “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” by way of a prolonged trial-and-error process, during which he produced many drawings and oil studies such as the one shown here. By the time he executed the Art Institute’s panel, he had already settled on the disposition of the landscape elements but was still experimenting with the figures, whose placement remains somewhat awkward. With its faceted handling and brilliantly orchestrated greens, blues, and yellows, the study has a charming immediacy. In the final canvas, however, the artist’s grave stylization and playful irony are more prominent, and the resulting tone is complex.

The distancing quality of Seurat’s novel technique made it a fine vehicle for his dry wit, evident in the occasional visual pun—note the wafts of cigar smoke that morph into a white dog -— as well as in remarkable gallery of contemporary social types, from the brooding rower reclining at the lower left to the gawky standing man playing a French horn in the middle distance. But the pervasive self-absorption of the figures seems at odds with the integrative harmonies of the composition as a whole. The painting is rich in such enigmatic tensions, which are perhaps the secret of its enduring fascination.

The “Grande Jatte” brought Seurat fame and made him the leader of an artistic school; many painters, notably Camille Pissarro and Paul Signac, chose to adopt Neo-Impressionism, as Seurat’s manner came to be known (it is also referred to as Pointillism or Divisionism). Although short-lived as a movement (largely due to Seurat’s untimely death, at age thirty-one), the style is historically important for its introduction into avant-garde painting of new elements —- such as the simplification of form, a classical mode of spatial organization, and a sophisticated sense of decorative unity. Basing his works on abstract schemes rather than pure sensation, Seurat opened wholly unforeseen possibilities for the development of modern art.

Seurat made the final changes to “La Grande Jatte” in 1889. He restretched the canvas in order to add a painted border of red, orange, and blue dots that provides a visual transition between the interior of the painting and his specially designed white frame.

(from the AIC website)

Much more of Seurat’s work appears in the MWW exhibit/gallery:

* The Other Impressionists II: Seurat & Signac

Post link

The Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, Claude Monet, 1908

Claude Monet- San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk, 1908

Edgar Degas, Ballet Dancers in the Wings, c.1890–1900

Weeping Willow1918, Claude Monet, oil on canvas.

Monet painted the weeping willow in his garden at Giverny in response to the horrors of the Great War. Grief is expressed through subject matter – the weeping willow is a traditional symbol of mourning – and through the sombre, expressive application of paint.

Post link

‘Woman with a Parasol’ - Madame Monet and Her Son (1875) by Claude Monet (1840–1926).

Oil on canvas.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C., online collection

Wikimedia.

Post link

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Two Sisters(On the Terrace), 1881, oil on canvas, 100.4 x 80.9 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago. Source

This is one of my all-time favourite Renoir paintings, and it also serves as the cover of TASCHEN’s Renoir. Painter of Happiness book, which never fails to brighten up my day.

Post link

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint Lazare Exterior, 1877

Villas at Trouville

Gustave Caillebotte (French; 1848–1894)

1884

Oil on canvas

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

Post link

![hit me up on insta [ x x ] hit me up on insta [ x x ]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/e94d10a4246cff3c2d380f952052fb0c/47c9c04ded2d57f5-f5/s500x750/058d6232147db4f9133ad9f4940ff60f575e4cf3.jpg)

![hit me up on insta [ x x ] hit me up on insta [ x x ]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/501086f1f7f6606b00b1323d0c5e4830/47c9c04ded2d57f5-4f/s500x750/8d765be6652bc71ecc24bf4e09127fee62a148c4.png)

![hit me up on insta [ x x ] hit me up on insta [ x x ]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/8e1a51bae43f24516ddca3ae7b497699/47c9c04ded2d57f5-b1/s500x750/98a7cb4b5fe0257bcd6ef743b986dbb879f75609.jpg)

![does anyone still care about this blog? legit questionxoxoMonet [x] does anyone still care about this blog? legit questionxoxoMonet [x]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/2911588b10d8acd1d12e1cde2edc2182/tumblr_pj4rrfjzJW1u3xsl3o1_500.jpg)